This review was originally published on the Minima Aesthetica Substack (click here to view), and is republished here with the author’s kind permission.

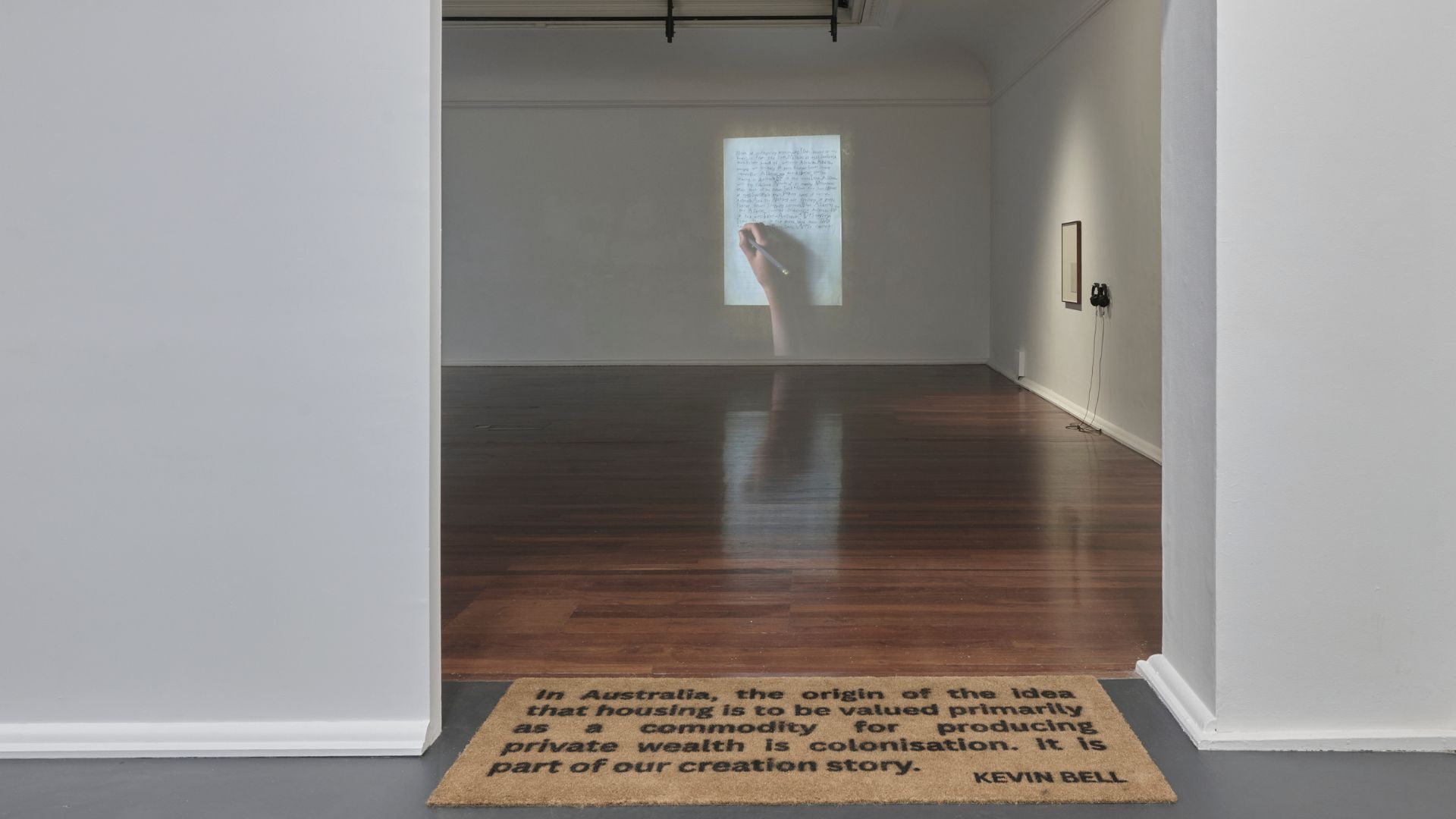

After visiting Alana Hunt’s solo show at PICA, I wondered if we, the contemporary art public, are becoming accustomed to asking too little of artists. Hunt’s exhibition occupied the entire ground floor of the gallery, and yet, when all is said and done, the only substantial work to be found was the video piece in the last room. This was a seemingly autobiographical narrative about growing up in various rented suburban houses as the child of a single mother; it was both lyrical and captivating.

The rest of the exhibition could be described as “quasi-didactic minimalism,” interspersed with—and redeemed by—biographical touches. All the works revolve around the relationship between home ownership as capital accumulation and the colonial expropriation of Aboriginal land. I am sympathetic to the topic. Like Alana Hunt, I never bothered to buy a home, and now I find myself infinitely poorer than the friends, family, and colleagues who understood the importance of a freehold title. On the plus side, I can boast that I don’t own stolen land; I just lease it! Contrary to leftist homeowners who, on certain public occasions, feel they must show contrition for owning land they admit is stolen but have no intention of returning, I can at least say: “Take it up with my landlord, that bastard!” Of course, it’s a flimsy defence, but it’s all Alana Hunt, and I have.

The exhibition implicitly divides the Australian population into three ethico-economic categories: those (the majority) who took advantage of the opportunity offered by home ownership and have now accumulated substantial brick-and-mortar equity; those too stupid (like me) or too young (like my daughter and perhaps Alana Hunt) to buy a home when it was still affordable; and the original owners, or custodians, of the land everyone else is busy buying, selling, leasing, upgrading, clearing, cultivating, subdividing, consolidating, entitling, rezoning, and flipping.

When asked why I never bought a home, I usually give one of two answers: “Home ownership turns you into a mini-Scrooge obsessed with maximising resale value and minimising taxes,” or “We buy a home because owning land and a building gives us an illusion of permanency that deceives us into thinking we are never going to die.” The reality is that, until very recently, I just didn’t bother with it. I always easily found suitable, affordable rentals.

It’s interesting to compare this show to exhibitions that focus on architectural, scientific, or historical content. In those instances, exhibitors, curators, and designers strive to make the material visually appealing and engaging. Anyone who has attended the Venice Biennale of Architecture or visited major science museums understands the various ways in which information can be transformed into spectacle.

However, contemporary post-conceptual artists like Hunt avoid spectacle at all costs because they are terrified of being accused of “aestheticisation.” For reasons that are not entirely clear, visual pleasure is now often frowned upon. This may sound odd if you think art has something to do with beauty, but the so-called “conceptual turn” brought about a rejection of art’s aesthetic dimension. As a result, exhibitions are now often duller, but at least artists with ideas but no aesthetic flair can have a shot at a career.

But thoughts don’t need rooms; they are what Descartes called res cogitans—an entity lacking a spatial dimension. Alana Hunt could have presented her pithy allusions to homeownership and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, as well as her poetic coming-of-age narrative, in book form. Given that the work is a critique of Australian attitudes toward home ownership, why did she need so much gallery real estate?

Hunt’s quasi-didacticism relies on unadorned artistic gestures that almost always utilise “readymades.” Handwritten documents, Plain Jane photographs of cars and homes, and excerpts from old documentaries and advertisements are displayed side-by-side to form an argument that, although not explicitly stated, is easily readable in its broad strokes. It is, however, an argument without an obvious conclusion, because the ethical-political dilemmas it raises have no easy solution.

Typically, contemporary artists who use readymades make them as indecipherable as possible. Given that these types of artistic devices result from the most basic signifying operation—ostension (the act of pointing at something)—we must assume that artists have a deep, meaningful, and therefore not immediately evident reason for drawing our attention to an ordinary object they have lifted from its original environment. Hence, the artwork’s mysterious and surprising depths of meaning are meant to redeem the procedure's extreme simplicity.

This, however, is not the case with this exhibition. It is instead quite readable, reinforcing the impression that we are looking at interpretive displays rather than artworks. It could be argued that it is refreshing to find an established artist who still values communicability, given that so many of her colleagues use crypticism as a pseudo-signifier of depth.

But I am a Kantian (of sorts), and I believe that artistic meaning must—yes, must—be indeterminate and ultimately undecidable. Indeterminacy, however, is not the same as unintelligibility. On the contrary, it implies an overflow of meaning, not its concealment. When experiencing a work of art, we should not find ourselves anxiously searching for missing meaning, as if we were looking for a lost wallet, but rejoicing in the overabundance of possible interpretations that spontaneously present themselves to our consciousness. Didactic art avoids the faux profond of deliberate artistic obfuscation but risks failing to deliver the richness and potential of truly successful art.

In her best works, Alana Hunt leaves interpretability open enough to engage our imagination. At other times, however, she limits herself to pointing a finger at what she wants us to reflect on. Unfortunately, the widespread abuse of the readymade in contemporary society has legitimised this kind of “less is more” approach. The truth is that “less” is too often simply not enough. I want more. I can point the finger myself; I don’t need an artist to do it for me.

But perhaps the ethical-political themes Hunt explores are so immense that any attempt to translate them into artworks would be overwhelming. Like the sun, they cannot be faced directly; they would blind us. This perhaps explains why the artist only hints at them, transforming them into barely perceptible echoes reflected in quotidian autobiographical narratives.

Alana Hunt, A Deceptively Simple Need, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 17 October – 21 December 2025.

Images: Alana Hunt, ‘A Deceptively Simple Need’ 2025, installation view, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), 2025. Photo: Rebecca Mansell.

After visiting Alana Hunt’s solo show at PICA, I wondered if we, the contemporary art public, are becoming accustomed to asking too little of artists. Hunt’s exhibition occupied the entire ground floor of the gallery, and yet, when all is said and done, the only substantial work to be found was the video piece in the last room. This was a seemingly autobiographical narrative about growing up in various rented suburban houses as the child of a single mother; it was both lyrical and captivating.

The rest of the exhibition could be described as “quasi-didactic minimalism,” interspersed with—and redeemed by—biographical touches. All the works revolve around the relationship between home ownership as capital accumulation and the colonial expropriation of Aboriginal land. I am sympathetic to the topic. Like Alana Hunt, I never bothered to buy a home, and now I find myself infinitely poorer than the friends, family, and colleagues who understood the importance of a freehold title. On the plus side, I can boast that I don’t own stolen land; I just lease it! Contrary to leftist homeowners who, on certain public occasions, feel they must show contrition for owning land they admit is stolen but have no intention of returning, I can at least say: “Take it up with my landlord, that bastard!” Of course, it’s a flimsy defence, but it’s all Alana Hunt, and I have.

The exhibition implicitly divides the Australian population into three ethico-economic categories: those (the majority) who took advantage of the opportunity offered by home ownership and have now accumulated substantial brick-and-mortar equity; those too stupid (like me) or too young (like my daughter and perhaps Alana Hunt) to buy a home when it was still affordable; and the original owners, or custodians, of the land everyone else is busy buying, selling, leasing, upgrading, clearing, cultivating, subdividing, consolidating, entitling, rezoning, and flipping.

When asked why I never bought a home, I usually give one of two answers: “Home ownership turns you into a mini-Scrooge obsessed with maximising resale value and minimising taxes,” or “We buy a home because owning land and a building gives us an illusion of permanency that deceives us into thinking we are never going to die.” The reality is that, until very recently, I just didn’t bother with it. I always easily found suitable, affordable rentals.

It’s interesting to compare this show to exhibitions that focus on architectural, scientific, or historical content. In those instances, exhibitors, curators, and designers strive to make the material visually appealing and engaging. Anyone who has attended the Venice Biennale of Architecture or visited major science museums understands the various ways in which information can be transformed into spectacle.

However, contemporary post-conceptual artists like Hunt avoid spectacle at all costs because they are terrified of being accused of “aestheticisation.” For reasons that are not entirely clear, visual pleasure is now often frowned upon. This may sound odd if you think art has something to do with beauty, but the so-called “conceptual turn” brought about a rejection of art’s aesthetic dimension. As a result, exhibitions are now often duller, but at least artists with ideas but no aesthetic flair can have a shot at a career.

But thoughts don’t need rooms; they are what Descartes called res cogitans—an entity lacking a spatial dimension. Alana Hunt could have presented her pithy allusions to homeownership and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, as well as her poetic coming-of-age narrative, in book form. Given that the work is a critique of Australian attitudes toward home ownership, why did she need so much gallery real estate?

Hunt’s quasi-didacticism relies on unadorned artistic gestures that almost always utilise “readymades.” Handwritten documents, Plain Jane photographs of cars and homes, and excerpts from old documentaries and advertisements are displayed side-by-side to form an argument that, although not explicitly stated, is easily readable in its broad strokes. It is, however, an argument without an obvious conclusion, because the ethical-political dilemmas it raises have no easy solution.

Typically, contemporary artists who use readymades make them as indecipherable as possible. Given that these types of artistic devices result from the most basic signifying operation—ostension (the act of pointing at something)—we must assume that artists have a deep, meaningful, and therefore not immediately evident reason for drawing our attention to an ordinary object they have lifted from its original environment. Hence, the artwork’s mysterious and surprising depths of meaning are meant to redeem the procedure's extreme simplicity.

This, however, is not the case with this exhibition. It is instead quite readable, reinforcing the impression that we are looking at interpretive displays rather than artworks. It could be argued that it is refreshing to find an established artist who still values communicability, given that so many of her colleagues use crypticism as a pseudo-signifier of depth.

But I am a Kantian (of sorts), and I believe that artistic meaning must—yes, must—be indeterminate and ultimately undecidable. Indeterminacy, however, is not the same as unintelligibility. On the contrary, it implies an overflow of meaning, not its concealment. When experiencing a work of art, we should not find ourselves anxiously searching for missing meaning, as if we were looking for a lost wallet, but rejoicing in the overabundance of possible interpretations that spontaneously present themselves to our consciousness. Didactic art avoids the faux profond of deliberate artistic obfuscation but risks failing to deliver the richness and potential of truly successful art.

In her best works, Alana Hunt leaves interpretability open enough to engage our imagination. At other times, however, she limits herself to pointing a finger at what she wants us to reflect on. Unfortunately, the widespread abuse of the readymade in contemporary society has legitimised this kind of “less is more” approach. The truth is that “less” is too often simply not enough. I want more. I can point the finger myself; I don’t need an artist to do it for me.

But perhaps the ethical-political themes Hunt explores are so immense that any attempt to translate them into artworks would be overwhelming. Like the sun, they cannot be faced directly; they would blind us. This perhaps explains why the artist only hints at them, transforming them into barely perceptible echoes reflected in quotidian autobiographical narratives.

Alana Hunt, A Deceptively Simple Need, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 17 October – 21 December 2025.

Images: Alana Hunt, ‘A Deceptively Simple Need’ 2025, installation view, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), 2025. Photo: Rebecca Mansell.