Russian linguist Roman Jakobson, in

his writings on the subject of translation, proposed three modes of

translation: interlingual, or a “word-for-word” translation of a text from one

language to another; intralingual, in which the translation expands to “rewording”

the text to reflect the tone, mood, and register of the original language; and

intersemiotic, in which a text is “translated” into another form or medium,

such as a film adaptation of a play. This third form—the intersemiotic—holds

particular potency when thinking through a series of buzzwords often used when

discussing contemporary art: that a work considers or speaks to a subject, or tells a story. Here, we see the

conflation of subject with narrative, confused, one might say, through the

intersemiotic translation of the artwork into description.

While this tension between art objects and the words we use to organise and communicate our thoughts on them has its own literature, rarely does it seem that critics approach their craft with a rhetorical style that, through any consistency, affirms to the reader an appreciation of this tension. On the other hand, such word games easily become distractions from addressing the work in earnest. What happens when the tension betweenlanguage and image is itself the tension at the heart of a work? For painter Nazila Jahangir, a silent prefix—mis—stands before interpretation: the desire to “read” her paintings, to narrativise them, is matched by an equal hesitation to “misread” them. This uneasiness underpins Jahangir’s exhibition of hyperreal paintings, Immigration, held earlier this year at Stala Contemporary.

Iranian-born Nazila Jahangir moved to Australia in 2019, before studying her MFA at the University of Western Australia. The campus itself is a source of visual imagery for Jahangir, with various buildings and locations appearing in her paintings, alongside other sites around Perth/Boorloo. The ten paintings comprising Immigration attest to Jahangir’s skill as a hyperrealist painter, their surfaces rendered in oil with a slick, satin, dreamlike finish. Art historical motifs abound—a translator’s delight—tempting the viewer to “read” the works as odes or homages to the history of art. Yet they remain distinctly removed from such didactic interpretations.

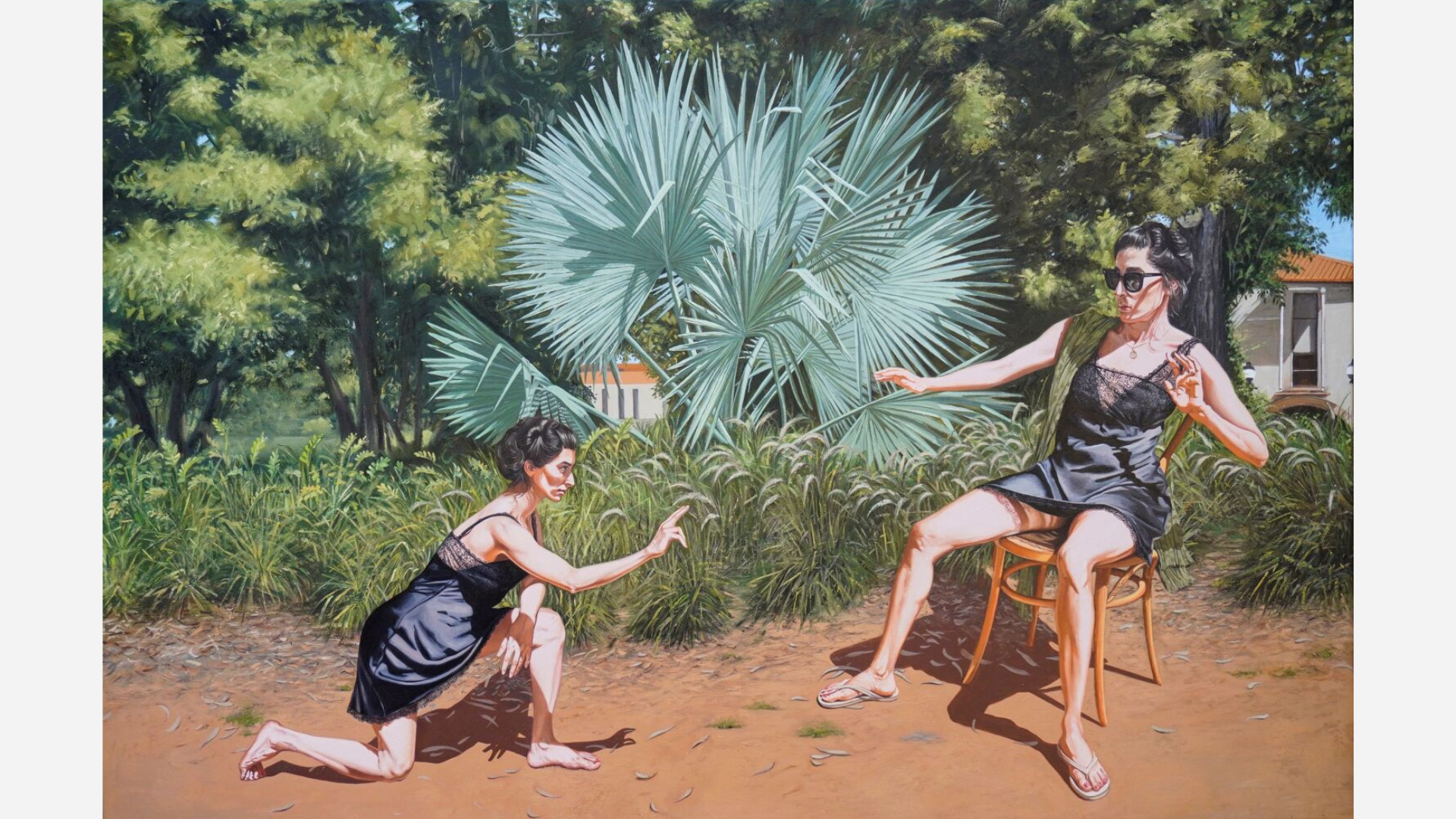

Immigration – Annunciation is one such example. Two figures—a double self-portrait—are depicted in the poses of Gabriel and Mary, blending elements of Leonardo da Vinci’s and Sandro Botticelli’s Annunciations (c. 1472 and c. 1489, respectively). From da Vinci, Jahangir borrows the positioning and spacing of the figures, along with their outdoor setting. From Botticelli’s more dramatic rendition, she reimagines the dynamic poses. While da Vinci’s scene occurs in an enclosed garden, or hortus conclusus—a Christian symbol of seclusion, purity, and paradise—Botticelli’s takes place within an interior space. Jahangir’s hortus conclusus is the UWA grounds. But this is no symbol of virginal purity. Instead, a hot, dry heat seems to beat down on the pair, both clad in silky black nighties. Jahangir’s “Mary” dons dark sunnies (perhaps she’s hungover) and beach thongs, while precariously leaning back on a bentwood chair (shocked by the appearance of her doppelgänger, perhaps). As you can see, even in describing the scene, the temptation to narrativise—to spin stories that go well beyond the symbolic cues that titillate the mind toward interpretation—is almost inescapable.

Jahangir describes this blend of familiar and unfamiliar imagery as a mix of “external and internal” motifs, combining memories and objects she brought with her from Iran with the sites and scenes of Perth/Boorloo. Infused with her adroit surrealist tendencies, the paintings strike me as hyperreal—but not in the typical artworld sense. Unlike the photorealism of Chuck Close or Robert Bechtle, Jahangir’s paintings recall Umberto Eco’s usage of the term in his essay Travels in Hyperreality, where he applies it to Madame Tussauds wax museums—where Abe Lincoln fraternises with JFK—and to casino replicas of iconic buildings from around the world. For Eco, the hyperreal is not merely a copy offering a one-to-one equivalence with an original (i.e. a lifelike JFK); rather, the hyperreal travels beyond reality, distorting and surpassing it. In Jahangir’s paintings, double likenesses surprise one another, hairdos defy gravity, and religious iconography is mimicked through contemporary hyper-localisms. These parts converge in unexpected ways, forming a subtle, interrelated chaos. It is the beyond-reality-ness of many of Jahangir’s paintings that might leave one uncomfortably tempted to describe them as surrealist. It is also their hyperreal qualities that invoke the sense that something is being lost in translation—that a slippage has occurred.

In this sense, the works elegantly realise Jahangir’s ambition to “show”, not “tell”, a migrant experience—where memories of the familiar meet the strangeness of the new, and where, as Homi K. Bhabha describes, the self is constantly in translation. What is most interesting to me about Jahangir’s overall project is that—rather than explaining or describing the experience—its ultimate aim appears to be the evocation of this intersemiotic confusion in the viewer.

Nazila Jahangir, Immigration, Stala Contemporary, 12 April – 11 May 2025.

Image credits:

1. Nazila Jahangir, Immigration – Annunciation, 2023, oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm.

2. Nazila Jahangir, Immigration – Waiting for Godot, 2024, oil on canvas, 70 x 100 cm.

3. Nazila Jahangir, Immigration – Chasing a Butterfly, 2024, oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm.

While this tension between art objects and the words we use to organise and communicate our thoughts on them has its own literature, rarely does it seem that critics approach their craft with a rhetorical style that, through any consistency, affirms to the reader an appreciation of this tension. On the other hand, such word games easily become distractions from addressing the work in earnest. What happens when the tension betweenlanguage and image is itself the tension at the heart of a work? For painter Nazila Jahangir, a silent prefix—mis—stands before interpretation: the desire to “read” her paintings, to narrativise them, is matched by an equal hesitation to “misread” them. This uneasiness underpins Jahangir’s exhibition of hyperreal paintings, Immigration, held earlier this year at Stala Contemporary.

Iranian-born Nazila Jahangir moved to Australia in 2019, before studying her MFA at the University of Western Australia. The campus itself is a source of visual imagery for Jahangir, with various buildings and locations appearing in her paintings, alongside other sites around Perth/Boorloo. The ten paintings comprising Immigration attest to Jahangir’s skill as a hyperrealist painter, their surfaces rendered in oil with a slick, satin, dreamlike finish. Art historical motifs abound—a translator’s delight—tempting the viewer to “read” the works as odes or homages to the history of art. Yet they remain distinctly removed from such didactic interpretations.

Immigration – Annunciation is one such example. Two figures—a double self-portrait—are depicted in the poses of Gabriel and Mary, blending elements of Leonardo da Vinci’s and Sandro Botticelli’s Annunciations (c. 1472 and c. 1489, respectively). From da Vinci, Jahangir borrows the positioning and spacing of the figures, along with their outdoor setting. From Botticelli’s more dramatic rendition, she reimagines the dynamic poses. While da Vinci’s scene occurs in an enclosed garden, or hortus conclusus—a Christian symbol of seclusion, purity, and paradise—Botticelli’s takes place within an interior space. Jahangir’s hortus conclusus is the UWA grounds. But this is no symbol of virginal purity. Instead, a hot, dry heat seems to beat down on the pair, both clad in silky black nighties. Jahangir’s “Mary” dons dark sunnies (perhaps she’s hungover) and beach thongs, while precariously leaning back on a bentwood chair (shocked by the appearance of her doppelgänger, perhaps). As you can see, even in describing the scene, the temptation to narrativise—to spin stories that go well beyond the symbolic cues that titillate the mind toward interpretation—is almost inescapable.

Jahangir describes this blend of familiar and unfamiliar imagery as a mix of “external and internal” motifs, combining memories and objects she brought with her from Iran with the sites and scenes of Perth/Boorloo. Infused with her adroit surrealist tendencies, the paintings strike me as hyperreal—but not in the typical artworld sense. Unlike the photorealism of Chuck Close or Robert Bechtle, Jahangir’s paintings recall Umberto Eco’s usage of the term in his essay Travels in Hyperreality, where he applies it to Madame Tussauds wax museums—where Abe Lincoln fraternises with JFK—and to casino replicas of iconic buildings from around the world. For Eco, the hyperreal is not merely a copy offering a one-to-one equivalence with an original (i.e. a lifelike JFK); rather, the hyperreal travels beyond reality, distorting and surpassing it. In Jahangir’s paintings, double likenesses surprise one another, hairdos defy gravity, and religious iconography is mimicked through contemporary hyper-localisms. These parts converge in unexpected ways, forming a subtle, interrelated chaos. It is the beyond-reality-ness of many of Jahangir’s paintings that might leave one uncomfortably tempted to describe them as surrealist. It is also their hyperreal qualities that invoke the sense that something is being lost in translation—that a slippage has occurred.

In this sense, the works elegantly realise Jahangir’s ambition to “show”, not “tell”, a migrant experience—where memories of the familiar meet the strangeness of the new, and where, as Homi K. Bhabha describes, the self is constantly in translation. What is most interesting to me about Jahangir’s overall project is that—rather than explaining or describing the experience—its ultimate aim appears to be the evocation of this intersemiotic confusion in the viewer.

Nazila Jahangir, Immigration, Stala Contemporary, 12 April – 11 May 2025.

Image credits:

1. Nazila Jahangir, Immigration – Annunciation, 2023, oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm.

2. Nazila Jahangir, Immigration – Waiting for Godot, 2024, oil on canvas, 70 x 100 cm.

3. Nazila Jahangir, Immigration – Chasing a Butterfly, 2024, oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm.