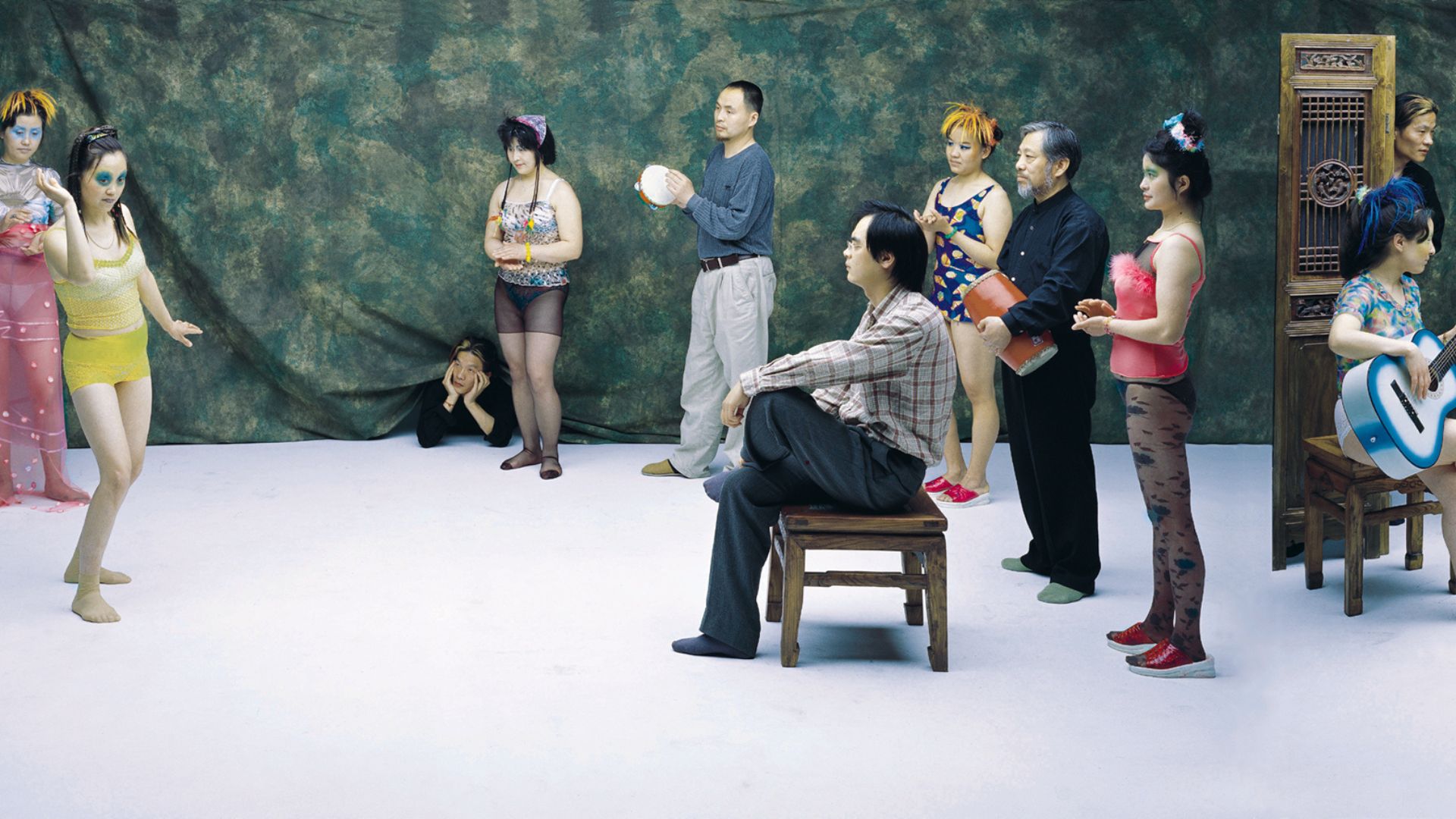

Against a marbled grey backdrop, a group of women clad in kitschy lingerie entertain a gathering of old men. Across five interconnected tableaux we see the women performing massages, playing wind instruments, dancing, strumming a guitar, and fawning over the men. The scene is at once uneasy and banal, unsettling and unremarkable. It is Wang Qingsong’s Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图, 2000), a metres-long photographic montage. The work is exemplary of Wang’s renowned large-scale staged photographs, but also of his penchant for historical reference and restaging. The revelry referenced is that of Han Xizai, the 10th century official of the Southern Tang Dynasty. Han grew a reputation as a talented advisor, captivating speaker, and fashionista, wooing his contemporaries with bespoke hats. As he served under successive emperors of the Southern Tang, his standing grew, but so too did the rumours of his overindulgence and his debaucherous parties. The young emperor Li Yu, the “Last Lord Li”, cottoned on to Han’s predilections. Eager to persuade Han to show restraint, Li enlisted the help of court painter Gu Gongzhong, who was instructed to infiltrate one of Han’s lurid parties. There, Gu was to collect evidence of decadence and debauchery, and record it in a painting—what would become the over three-metre-long handscroll, Night Revels of Han Xizai (韩熙载夜宴图), which today is held in the Imperial Palace Collection, Beijing. Among the scenes of partying performers and guests, we see Gu lurking in the background, glum and detached. Roughly one thousand years later, in Night Reels of Lao Li, Wang casts himself as the indifferent Gu, and his friend and esteemed art critic Li Xianting as Han Xizai—the titular “Lao” being a designation used for a respected familiar senior. In Wang’s version, the escorts are clad in gaudy garments, the banquets now consist of cheap crisps, Coca-Cola and cognac, and Wang (as Gu) is seen hiding behind a metal wastebin. Perhaps Wang’s pastiche of Tang Dynasty decadence suggests a contemporary underbelly of overindulgence and exploitation among the hierarchies of today’s bureaucracy. It also wryly reflects the tensions and anxieties of a culture undergoing monumental economic changes—in one image, the antagonisms of a venerated antiquity and commodified modernity emerge.

Night Revels is among twelve well known works included in Everlasting Inscription, Wang Qingsong’s debut solo exhibition in Australia. But, here in Perth, you won’t see Wang’s photography in a conventional gallery. Curated by Tami Xiang and Darren Jorgensen, Everlasting Inscription follows the pair’s 2023 exhibition Beijing Realism, held at Goolugatup Heathcote as part of the Perth Festival. Beijing Realism was the subject of media scrutiny, astonishingly, for a perceived anti-China stance. The unfounded criticism was distorted into an ethical question by ArtsHub, which presented a veiled accusation of exploitation and cultural insensitivity—even while the bulk of the artists in Beijing Realism were primarily Chinese mainlanders, all of whom well-regarded within the contemporary Chinese art scene.[1] Perhaps the criticism was allowed to foment due to the pervasive ignorance of many in WA’s art media with regard to contemporary Chinese art. Regardless, Goolugatup stood steadfast. Yet, it appears the slight and unconvincing controversy was enough to trigger nerves about this subsequent project—Wang Qingsong’s solo exhibition, having been pitched to several institutional galleries, remained without a taker. Perhaps this nervousness was compounded by the way Wang’s complex, ambiguous, and detailed photographs erupt with a sense of the political that resists deciphering and simple explanations. Surely, as one of China’s most celebrated photographers—who exploded onto the international artworld in Wang Chunchen’s groundbreaking Chinese Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013—Wang Qingsong would have made an excellent followup to recent photography exhibitions of Nan Goldin, Henry Roy or Sam Contis at a more mainstream institution.

Nonetheless, Xiang and Jorgensen persevered: they booked the Cullity Gallery at UWA’s School of Design; ordered high-quality prints direct from China; organised a rowdy mob of students to paint the walls; and mounted the show within 48 hours. The installation of Everlasting Inscription is rough, rushed, and even crude. However, these are the circumstances that so many of China’s contemporary artists are used to—working quickly within circumstances outside of their control, and largely in defiance of the institutions that ought support them. So, in this way, the lack of support offered to Wang by Perth’s major galleries has resulted in an exhibition that is perhaps even more reflective of the circumstances encountered by those contemporary Chinese artists whose work circulates in alternative spaces, private shows, and is created through clandestine methods. Regardless of all its punk DIY-ness, Everlasting Inscription is a landmark moment for Perth: the first solo exhibition from one of China’s leading contemporary photographers that ambitiously collates Wang’s most well-known works. These are photographs that simply cannot be replicated in books. Only when seen in such monumental scale do the intricate details emerge to reveal the richness of these photographs.

Born in Daqing, in the northeastern province of Heilongjiang, the road to art school was a long march for Wang Qingsong. After the discovery of oil in Daqing in 1959, the city became known as the “Oil Capital of China”—its deposits being the largest in the country. Wang’s father worked in the oil fields. At an artist talk held at the Cullity Gallery, Wang recounted how his father passed away when he was still a child. As a boy, he desired to follow in his father’s footsteps, and began work as an oil driller. During the 1980s, young people generally carried on the occupations of their parents, particularly in rural areas. By the time the young Wang began working for the oil company, few of his colleagues remembered his father—such was the pace of work—and Wang soon became despondent with the rough, laborious work. Wang recalled realising there was no way out. Then, one day, his mother told him of a friend’s son who had applied for art school and encouraged Wang to do the same.[2] Wang went five times to the national examinations held in July—yet, it was “so competitive, only one out of two thousand get in. In the 1980s and 1990s there were only eight academies, and each academy could only take twenty or thirty students.”[3] Eventually, enrolment requirements changed, and Wang was able to attend the renowned Sichuan Academy of Art.

Wang initially focused on painting, but soon took up the camera—finding in photography a means to realise his theatrical and hyper-referential creative vision. Everlasting Inscription samples his development as a photographer: his earlier works Requesting Buddha Series No. 1 (拿来千手观音系列之一, 1999), Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图, 2000), and the immense Dormitory (宿舍, 2005) are all exemplary of Wang’s experimentations in Photoshop, some of which are subtle and others overt; meanwhile Dream of Migrant (盲流梦, 2005) and The Blood of the World (世界的血, 2006) are indicative of Wang’s shift in interest toward meticulous large-scale sets; and the more recent Work! Work! Work! (工作!工作!再工作!, 2012) and The Blood-stained Shirt (血衣, 2018) illustrate Wang’s commitment to carefully orchestrated scenes, but this time using real-world locations rather than studios (the former shot in the architectural firm of Ole Scheeren, who designed the famous Beijing CCTV Headquarters colloquially referred to as the “big boxer shorts” (大裤衩), and the latter photographed at the site of a burned-out warehouse in Detroit).

![]()

To some, Wang’s photography may appear too convoluted and referential to warrent censorship. Yet, it is precisely the convolution—the kaleidoscope of items, symbols, and objects within the photographs—that allows Wang’s pointed political critiques to occur at all. In some respects, one might conceive of Wang’s photographic practices as a kind of collaboration with the censors themselves—preemptively developing elements within the compositions that provide Wang with explanations that he might use when attempting to ameliorate the censors’ concerns. Conversely, censors of Wang’s photography have also found inventive ways to interrupt his work. The Blood of the World is a fascinating example: in the upper portion of the photograph, a grisly battlefield is staged. Examination of the “battlefield” portion of the image reveals myriad historical references: a restaging of the famous 1968 Vietnam War image, Saigon Execution, by photojournalist Eddie Adams; an allusion to Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) and Goya’s The Third of May 1808 in Madrid (1814)—the latter looking as much like an ‘80s office worker as it does a Spanish rioter facing execution by Napoleon's forces. Naked bodies and tonnes of cow carcasses are scattered over the churned soil. Then toward the lower portion of the image, we see Wang directing his crew and actors, shattering any illusion that this is anything but a studio set. This “behind-the-scenes” photograph is not how Wang envisaged The Blood of the World. Not long after this image was taken, police arrived at the warehouse, tipped off about the production. Under the premise that some kind of strange pornography was being filmed, police suspended the production. Wang was arrested and imprisoned for a few nights. What photographs had been taken, up until the tip-off, were confiscated, and have never been seen since. All that survived is this behind-the-scenes shot, taken by one of Wang’s entourage—thus turning The Blood of the World into both a record of Wang’s process and of his relationship with censorship.

Here in Australia, censorship is far less overt. At the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand’s 2025 Conference held at UWA (where Wang Qingsong was a keynote), two panels addressed various aspects of censorship in an Australian context. While the censorship of art in Australia has a long history, it also presents a recurring narrative structure that suggests that Australians, by and large, have a low tolerance for censorship. The narrative arc often proceeds as follows: an artwork is proposed or presented publicly in some form; a controversy ensues, often driven by conservative media commentary; institutions or governments intervene, buckling under the perceived furor; this is followed by an artworld and public backlash (something along the lines of “don’t tell me what I’m allowed to see!”); and, finally, the contested artwork is reinstated, at the very least symbolically. This is a simplistic generalisation to be sure, but it appears to me to explain, in part, why we think of these censorious events as “instances” rather than indicative or exemplary of an aspect of Australian culture (that we have a history of censorship that must be reconciled). Moreover, Australian censorship is far more subtle. As Grace Slonim drew attention to in her panel session, increasingly we see the use of interpretive language by funding bodies (like ‘quality’, ‘impact’, and ‘timeliness’, all used by Creative Australia), which, Slonim argued, leaves the awarding of these grants difficult to scrutinise. Conversely, such criteria might encourage artists to pursue particular types of work; subjects and styles that have proven successful. Now, fads and trends are nothing new—but nevertheless, the difficulty we seem to have in scrutinising the kind of influence government grants and corporatised funding bodies are having on the arts suggest that these aren’t simple fashion trends at stake. Wang Qingsong likens the relationship between Chinese artists and officials to a match of ping-pong (an image that proves unexpectedly instructive in an Australian context too): it’s about ‘playing the edges’. A little too far and you’re off the table; too central and you’re helping the opponent; play the edge and you glide right past. You win. And, on this count, Everlasting Inscription is a victory—offering a unique presentation of Wang’s renowned photography, and his penetrating observations on the complexities and anxieties of China’s globalisation at the turn of the twenty-first century.

Wang Qingsong, Everlasting Inscription, Cullity Gallery at the UWA School of Design, 6 December 2025 – 28 February 2026.

Footnotes:

1. See Jo Pickup and Celina Lei, “Curators’ Responsibilities in Spotlight as Chinese Audiences Feel ‘Let Down,’” ArtsHub, March 24, 2023, https://www.artshub.com.au/news/news/curators-responsibilities-chinese-audiences-perth-festival-2621803/; Sam Beard, “Being Realistic,” Dispatch Review, April 7, 2023, https://dispatchreview.info/Being-Realistic; Darren Jorgensen and Tami Xiang, “Chinese Art in Australia: Beijing Realism and the Ethics of Exhibition Making,” ArtsHub, April 12, 2023, https://www.artshub.com.au/news/opinions-analysis/chinese-art-in-australia-beijing-realism-and-the-ethics-of-exhibition-making-2625850/.

2. Darren Jorgensen, “A Conversation with Wang Qingsong,” Guan Kan Journal, March 20, 2020, https://www.guankanjournal.art/journalessays/a-conversation-with-wang-qingsong?rq=wang%20qingsong

3. Ibid.

Images:

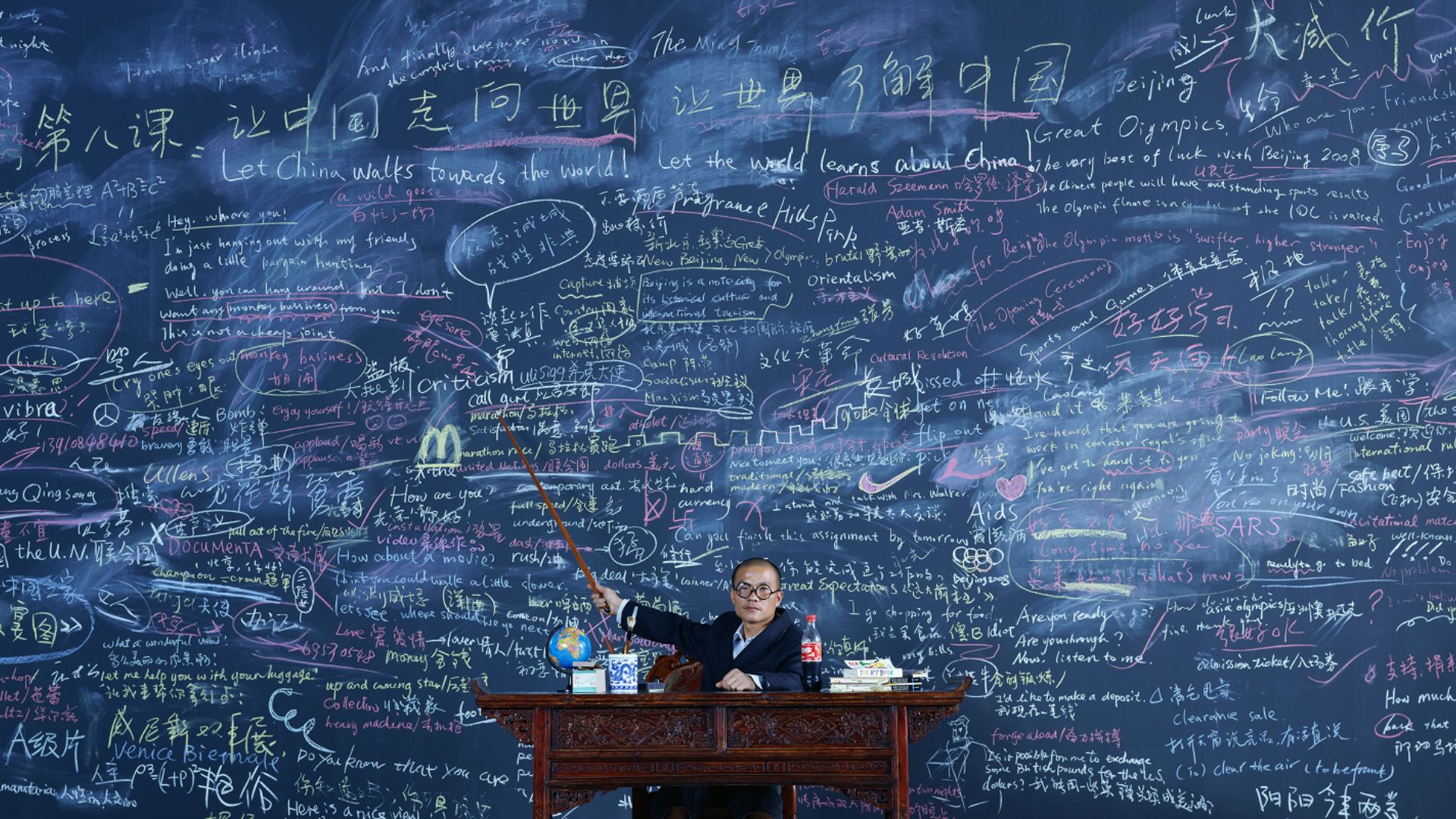

1. Wang Qingsong, Follow Me (跟我学, detail), 2003.

2. Wang Qingsong, Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图), 2000.

3. Wang Qingsong, Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图, detail), 2000.

4. Wang Qingsong, Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图, detail), 2000.

5. Wang Qingsong, The Blood-stained Shirt (血衣), 2018.

Night Revels is among twelve well known works included in Everlasting Inscription, Wang Qingsong’s debut solo exhibition in Australia. But, here in Perth, you won’t see Wang’s photography in a conventional gallery. Curated by Tami Xiang and Darren Jorgensen, Everlasting Inscription follows the pair’s 2023 exhibition Beijing Realism, held at Goolugatup Heathcote as part of the Perth Festival. Beijing Realism was the subject of media scrutiny, astonishingly, for a perceived anti-China stance. The unfounded criticism was distorted into an ethical question by ArtsHub, which presented a veiled accusation of exploitation and cultural insensitivity—even while the bulk of the artists in Beijing Realism were primarily Chinese mainlanders, all of whom well-regarded within the contemporary Chinese art scene.[1] Perhaps the criticism was allowed to foment due to the pervasive ignorance of many in WA’s art media with regard to contemporary Chinese art. Regardless, Goolugatup stood steadfast. Yet, it appears the slight and unconvincing controversy was enough to trigger nerves about this subsequent project—Wang Qingsong’s solo exhibition, having been pitched to several institutional galleries, remained without a taker. Perhaps this nervousness was compounded by the way Wang’s complex, ambiguous, and detailed photographs erupt with a sense of the political that resists deciphering and simple explanations. Surely, as one of China’s most celebrated photographers—who exploded onto the international artworld in Wang Chunchen’s groundbreaking Chinese Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013—Wang Qingsong would have made an excellent followup to recent photography exhibitions of Nan Goldin, Henry Roy or Sam Contis at a more mainstream institution.

Nonetheless, Xiang and Jorgensen persevered: they booked the Cullity Gallery at UWA’s School of Design; ordered high-quality prints direct from China; organised a rowdy mob of students to paint the walls; and mounted the show within 48 hours. The installation of Everlasting Inscription is rough, rushed, and even crude. However, these are the circumstances that so many of China’s contemporary artists are used to—working quickly within circumstances outside of their control, and largely in defiance of the institutions that ought support them. So, in this way, the lack of support offered to Wang by Perth’s major galleries has resulted in an exhibition that is perhaps even more reflective of the circumstances encountered by those contemporary Chinese artists whose work circulates in alternative spaces, private shows, and is created through clandestine methods. Regardless of all its punk DIY-ness, Everlasting Inscription is a landmark moment for Perth: the first solo exhibition from one of China’s leading contemporary photographers that ambitiously collates Wang’s most well-known works. These are photographs that simply cannot be replicated in books. Only when seen in such monumental scale do the intricate details emerge to reveal the richness of these photographs.

Born in Daqing, in the northeastern province of Heilongjiang, the road to art school was a long march for Wang Qingsong. After the discovery of oil in Daqing in 1959, the city became known as the “Oil Capital of China”—its deposits being the largest in the country. Wang’s father worked in the oil fields. At an artist talk held at the Cullity Gallery, Wang recounted how his father passed away when he was still a child. As a boy, he desired to follow in his father’s footsteps, and began work as an oil driller. During the 1980s, young people generally carried on the occupations of their parents, particularly in rural areas. By the time the young Wang began working for the oil company, few of his colleagues remembered his father—such was the pace of work—and Wang soon became despondent with the rough, laborious work. Wang recalled realising there was no way out. Then, one day, his mother told him of a friend’s son who had applied for art school and encouraged Wang to do the same.[2] Wang went five times to the national examinations held in July—yet, it was “so competitive, only one out of two thousand get in. In the 1980s and 1990s there were only eight academies, and each academy could only take twenty or thirty students.”[3] Eventually, enrolment requirements changed, and Wang was able to attend the renowned Sichuan Academy of Art.

Wang initially focused on painting, but soon took up the camera—finding in photography a means to realise his theatrical and hyper-referential creative vision. Everlasting Inscription samples his development as a photographer: his earlier works Requesting Buddha Series No. 1 (拿来千手观音系列之一, 1999), Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图, 2000), and the immense Dormitory (宿舍, 2005) are all exemplary of Wang’s experimentations in Photoshop, some of which are subtle and others overt; meanwhile Dream of Migrant (盲流梦, 2005) and The Blood of the World (世界的血, 2006) are indicative of Wang’s shift in interest toward meticulous large-scale sets; and the more recent Work! Work! Work! (工作!工作!再工作!, 2012) and The Blood-stained Shirt (血衣, 2018) illustrate Wang’s commitment to carefully orchestrated scenes, but this time using real-world locations rather than studios (the former shot in the architectural firm of Ole Scheeren, who designed the famous Beijing CCTV Headquarters colloquially referred to as the “big boxer shorts” (大裤衩), and the latter photographed at the site of a burned-out warehouse in Detroit).

Above: Wang Qingsong,

The Blood of the World (世界的血), 2006.

To some, Wang’s photography may appear too convoluted and referential to warrent censorship. Yet, it is precisely the convolution—the kaleidoscope of items, symbols, and objects within the photographs—that allows Wang’s pointed political critiques to occur at all. In some respects, one might conceive of Wang’s photographic practices as a kind of collaboration with the censors themselves—preemptively developing elements within the compositions that provide Wang with explanations that he might use when attempting to ameliorate the censors’ concerns. Conversely, censors of Wang’s photography have also found inventive ways to interrupt his work. The Blood of the World is a fascinating example: in the upper portion of the photograph, a grisly battlefield is staged. Examination of the “battlefield” portion of the image reveals myriad historical references: a restaging of the famous 1968 Vietnam War image, Saigon Execution, by photojournalist Eddie Adams; an allusion to Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) and Goya’s The Third of May 1808 in Madrid (1814)—the latter looking as much like an ‘80s office worker as it does a Spanish rioter facing execution by Napoleon's forces. Naked bodies and tonnes of cow carcasses are scattered over the churned soil. Then toward the lower portion of the image, we see Wang directing his crew and actors, shattering any illusion that this is anything but a studio set. This “behind-the-scenes” photograph is not how Wang envisaged The Blood of the World. Not long after this image was taken, police arrived at the warehouse, tipped off about the production. Under the premise that some kind of strange pornography was being filmed, police suspended the production. Wang was arrested and imprisoned for a few nights. What photographs had been taken, up until the tip-off, were confiscated, and have never been seen since. All that survived is this behind-the-scenes shot, taken by one of Wang’s entourage—thus turning The Blood of the World into both a record of Wang’s process and of his relationship with censorship.

Here in Australia, censorship is far less overt. At the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand’s 2025 Conference held at UWA (where Wang Qingsong was a keynote), two panels addressed various aspects of censorship in an Australian context. While the censorship of art in Australia has a long history, it also presents a recurring narrative structure that suggests that Australians, by and large, have a low tolerance for censorship. The narrative arc often proceeds as follows: an artwork is proposed or presented publicly in some form; a controversy ensues, often driven by conservative media commentary; institutions or governments intervene, buckling under the perceived furor; this is followed by an artworld and public backlash (something along the lines of “don’t tell me what I’m allowed to see!”); and, finally, the contested artwork is reinstated, at the very least symbolically. This is a simplistic generalisation to be sure, but it appears to me to explain, in part, why we think of these censorious events as “instances” rather than indicative or exemplary of an aspect of Australian culture (that we have a history of censorship that must be reconciled). Moreover, Australian censorship is far more subtle. As Grace Slonim drew attention to in her panel session, increasingly we see the use of interpretive language by funding bodies (like ‘quality’, ‘impact’, and ‘timeliness’, all used by Creative Australia), which, Slonim argued, leaves the awarding of these grants difficult to scrutinise. Conversely, such criteria might encourage artists to pursue particular types of work; subjects and styles that have proven successful. Now, fads and trends are nothing new—but nevertheless, the difficulty we seem to have in scrutinising the kind of influence government grants and corporatised funding bodies are having on the arts suggest that these aren’t simple fashion trends at stake. Wang Qingsong likens the relationship between Chinese artists and officials to a match of ping-pong (an image that proves unexpectedly instructive in an Australian context too): it’s about ‘playing the edges’. A little too far and you’re off the table; too central and you’re helping the opponent; play the edge and you glide right past. You win. And, on this count, Everlasting Inscription is a victory—offering a unique presentation of Wang’s renowned photography, and his penetrating observations on the complexities and anxieties of China’s globalisation at the turn of the twenty-first century.

Wang Qingsong, Everlasting Inscription, Cullity Gallery at the UWA School of Design, 6 December 2025 – 28 February 2026.

Footnotes:

1. See Jo Pickup and Celina Lei, “Curators’ Responsibilities in Spotlight as Chinese Audiences Feel ‘Let Down,’” ArtsHub, March 24, 2023, https://www.artshub.com.au/news/news/curators-responsibilities-chinese-audiences-perth-festival-2621803/; Sam Beard, “Being Realistic,” Dispatch Review, April 7, 2023, https://dispatchreview.info/Being-Realistic; Darren Jorgensen and Tami Xiang, “Chinese Art in Australia: Beijing Realism and the Ethics of Exhibition Making,” ArtsHub, April 12, 2023, https://www.artshub.com.au/news/opinions-analysis/chinese-art-in-australia-beijing-realism-and-the-ethics-of-exhibition-making-2625850/.

2. Darren Jorgensen, “A Conversation with Wang Qingsong,” Guan Kan Journal, March 20, 2020, https://www.guankanjournal.art/journalessays/a-conversation-with-wang-qingsong?rq=wang%20qingsong

3. Ibid.

Images:

1. Wang Qingsong, Follow Me (跟我学, detail), 2003.

2. Wang Qingsong, Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图), 2000.

3. Wang Qingsong, Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图, detail), 2000.

4. Wang Qingsong, Night Revels of Lao Li (老栗夜宴图, detail), 2000.

5. Wang Qingsong, The Blood-stained Shirt (血衣), 2018.