Hatched Dispatched 2025

Saturday, 23 August 2025

The 2025 Hatched exhibition is by far the most spacious iteration of the national graduate exhibition, having been relocated into a temporary venue in Forrest Chase while renovations take place at PICA. Five critics visited the exhibition, and offer their insights here on

the particular works they were drawn to. For

Nalinie

See and Kye Fisher, Grace Yong’s 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology) prompted two

divergent responses to one of the central aspects of the work. Jess van Heerden

examines the pastels of Silki Wong’s Grip and skatepark iconography of Nicole Goode’s Linger. Maraya Takoniatis offers a close reading of Germaine Chan’s

painting It’s the Revelation along

with some reflections on the upward trajectory of the exhibition from last

year. Riley Landau reflects on the innovative methods of image-making used by Litia

Roko and Pippini Niamh, whose respective uses of digital media and printmaking break from expectations. The 2025 Dr Harold Schenberg Arts

award winners include Samuel Chan for his sculptures, of which Transfiguration is among his most

impressive, Tom Duffy’s thought-provoking (yet, to my mind, somewhat unresolved) paintings Djagats (The Newly Arrived/Native Dignity),

and Grace Yong’s pensive video 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology). Artworks by a

further 20 graduates are included in this year’s exhibition, which runs until 5

October 2025—and with the following thoughts of these critics in mind, I will

certainly be revisiting before then.

![]()

Germaine Chan, It’s the Revelation

The jumble of exposed beams, air vents, and modern skylights in PICA’s Forrest Chase venue for Hatched 2025 unexpectedly elevated the annual graduate show. Finally, young artists were placed in a room that reflected the world their generation experiences: gritty, exposed and over-engineered. The context of this fresh venue gave the works greater relevance and timeliness, even though overall there was a strong material and conceptual adherence to the previous iterations of the exhibition—after all, the arts students may change, but the art educations they receive year after year primarily remain the same. One surprising development was the selection of a contemporary painting from UWA, whose Hatched contributions in recent years have evidenced a preference for students embracing less-traditional mediums (in contrast with Curtin, which routinely champions its graduating painters). UWA student and mixed media artist Germaine Chan’s contribution to Hatched, It’s the Revelation, revives historical religious painting for a contemporary context. Across her panoramic scenes, Chan’s assorted fragments of morally dubious stick-figures in ugly, human gesticulations offer a discursive reflection on contemporary inter-personal entanglements. But Chan’s genius is not in the story she tells. The real highlight of It’s the Revelation is that despite sharing with almost every other work at Hatched the feature of visually ambiguous composition, it engages this contemporary convention without compromising Chan’s idiosyncratic expression and singular artistic identity. It is this kind of artistic innovation, of using ubiquitous and stale tools to solidify one’s distinctive artistic identity, that sees Chan carving out a space for herself within—what usually feels like—a cyclical contemporary artworld. Chan’s repackaging of a ubiquitous way of working resonates with Hatched 2025, which is itself an unironic attempt to restyle the old, improving it, whilst bypassing the struggle of starting from scratch. These innovations prove that consistency does not require conformity and that Hatched may still have more to give us.

![]()

Litia Roko, 500mL/point

In today’s world, it’s a Sisyphean task to locate an artist who hasn’t been affected by the rise of generative artificial intelligence. A society already inundated with a crippling inability to engage in arts, now believes that meaningful images can be produced by an algorithm regurgitating probabilistic pixels and slop. It is no surprise a collective exhibition of recently graduated and emerging artists would grapple with this existential challenge. Litia Roko’s work 500 mL/point satirises this looming challenge to art practices by presenting her own cost benefit analysis of using AI. The name itself refers to the drastic water usage AI servers require to prevent themselves from combusting. The most resonant area of her video was the open criticism of the Living Museum App. This supposedly pedagogical resource claims to use AI to bring objects from the British Museum to life. The ethical authority of western programs—notorious for their wealth of stolen heritage—is already obviously problematic, yet Roko’s video intensifies the distressing qualities of rampant AI, reflecting its true scale. She draws attention to the ways that algorithms privilege the information they have been fed, and how this can be weaponised to produce narratives that obscure and mystify the truth. For instance, in 500mL/point a Moai head claims, “I love it here,” though of course it can only speak with what data it has been fed. By so openly confronting the issues that arise when artistic practice melds with generative machinery, Roko’s work leaves any viewer more assured of the absolute inherent and indispensable worth of the human element in artistic and academic practices.

![]()

Nicole Goode, Linger (grind rail) and Linger (break ramp)

Nicole Goode’s unsettling works—that is, works of unsettling—speak, wordlessly, of unbecoming. Set in negative space, the two-part performance is characterised by bared underbelly, exposed neck, and implied promises unfulfilled. It is in its “un”s, its negations, that the work becomes most concrete; the artist’s untimely body, graceful and irregular in its slowness, is less of a focal point than the disruptions that its presence creates. Linger (grind rail), Goode’s 60 minute movement performance (enacted on opening night), offered an eerie screen-to-life mirroring of Linger (break ramp), a 65-minute single-channel colour video that flickers projected from floor to ceiling upon the entry wall of PICA’s temporary warehouse abode. The live performance saw Goode entangle themselves carefully around and through the work’s metallic namesake. The steady delicateness of the artist’s extended limbs and arched frame gave the impression that Goode was supported by thickened honey. Goode’s subversive employment of skating equipment, a particularly austere steel frame exposed here and there under peeling cobalt paint, created a site of contestation. This unexpected mode of relating rendered sharply the lack of bodies and movements one anticipated. Through absence and aversion, Goode prompts the consideration of patterns of exclusion in a masculine-coded space. The discomfort afforded by Goode’s displacement was enhanced by a breakdown of typically contractual audience/performer relations. Subverting developmental logic, and reaching towards viewers with an almost unblinking gaze, Goode’s durational piece lived in the margins of social intelligibility. Disruption, however, was not manifested in distance. The artist’s bodily presence throughout Linger (grind rail) emphasised, with weighted physicality, the vulnerability implicit in “resisting expectations of movement and progress,” instilling the performance with tenderness. Softness is central, too. In Linger (break ramp), the artist tumbles down a large skate ramp (in what began as excruciatingly slow motion, until I settled into this new rhythm about ten minutes in). Goode’s performance borrows from skateboarders’ failures: the angular contortion of limbs and twisting of spines, wrapping each progression in fluidity and care. Even so, viewership is not an entirely peaceful experience. For at the heels of each gentle gesture snaps violence not yet rested into tangible form. Just as gravity seems to recognise it is robbed of crunched bone and split skin, so too is violence evoked by the slanted stares, dinged BMX bells, and chuckling leers of teenagers passing through the video’s frame. Imitation silver chains and hoodies emblazoned, like the park, with text bursting into spearheads where serifs should be, are unsettled by this quiet intervention. Goode’s temporality-warping acts of queering prompt consideration of alternative ways of being and moving within this ‘public’ space.

![]()

Grace Yong, 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology)

I can’t speak for everyone, but as a Southeast Asian woman raised in Western culture, I’ve often found myself in fascinating conversations with friends about the tradition of women taking their partner’s surname. Some of us imagine keeping our birth names, others consider hyphenation, and a fair few embrace the tradition. Grace Yong’s her name, an anthology, shown at this year’s Hatched, feels like an invitation to extend those conversations through a different cultural and historical lens. Gentle and introspective, the work is elegantly and thoughtfully composed, unfolding layers of meaning that invite the viewer to pause and reflect on the art of names. The video traces the way names carry lineage, tradition, and quiet currents of power, shaped by the push and pull of matriarchal and patriarchal customs. Layering image and text, it opens space for viewers to consider not just what a name means, but how it binds us to ancestry, shapes our sense of gender, and reflects the expectations of the world we move through. In earnest, I had low expectations for this video because it initially seemed overly direct and plain; yet, there is a quiet persistence to it. It’s the kind of work that lingers in your mind, unfolding its depth slowly, like a book you return to repeatedly, noticing something new each time. At certain moments, I found myself quietly enraged and confused, particularly when Yong uses phrases like “when she became a daughter” or “when she became a wife” to describe her great-grandmother’s name change. These words highlight a disheartening reality that as women, our surnames—our link to family and legacy—rarely stay with us or pass down through the maternal line. At birth, we are our father’s daughters; in marriage, our husbands’ wives; and the children we bear carry his name. Perhaps some of my frustration mirrors that of another Hatched nominee, whose work reflects on the biological truth that a woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have, formed while she is still a fetus inside her mother’s womb. In carrying a child, she also carries the potential for the eggs of her future grandchildren. But I digress. Watching Yong’s work, I felt a mixture of hurt, confusion, and indignation, torn between respect for tradition and frustration with a social practice that often feels arbitrary. However, I should clarify that I am not here to dictate whether anyone should keep, change, or hyphenate their surname; it is a deeply personal choice and one I remain uncertain of myself. Still, the work leaves you with a lingering awareness of how deeply names shape identity, lineage, and those quiet, often invisible, structures of gender in our lives.

![]()

Grace Yong, 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology)

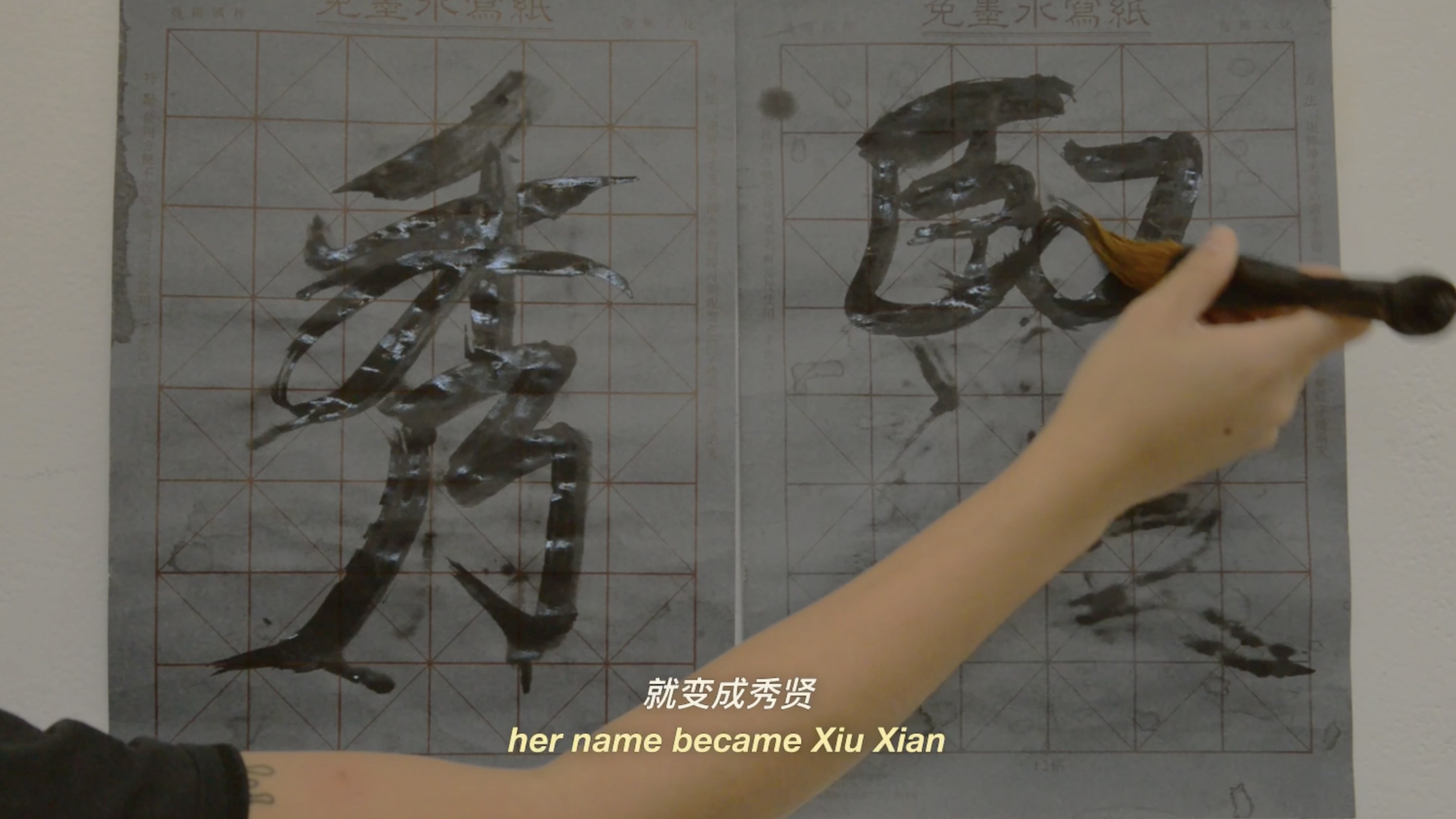

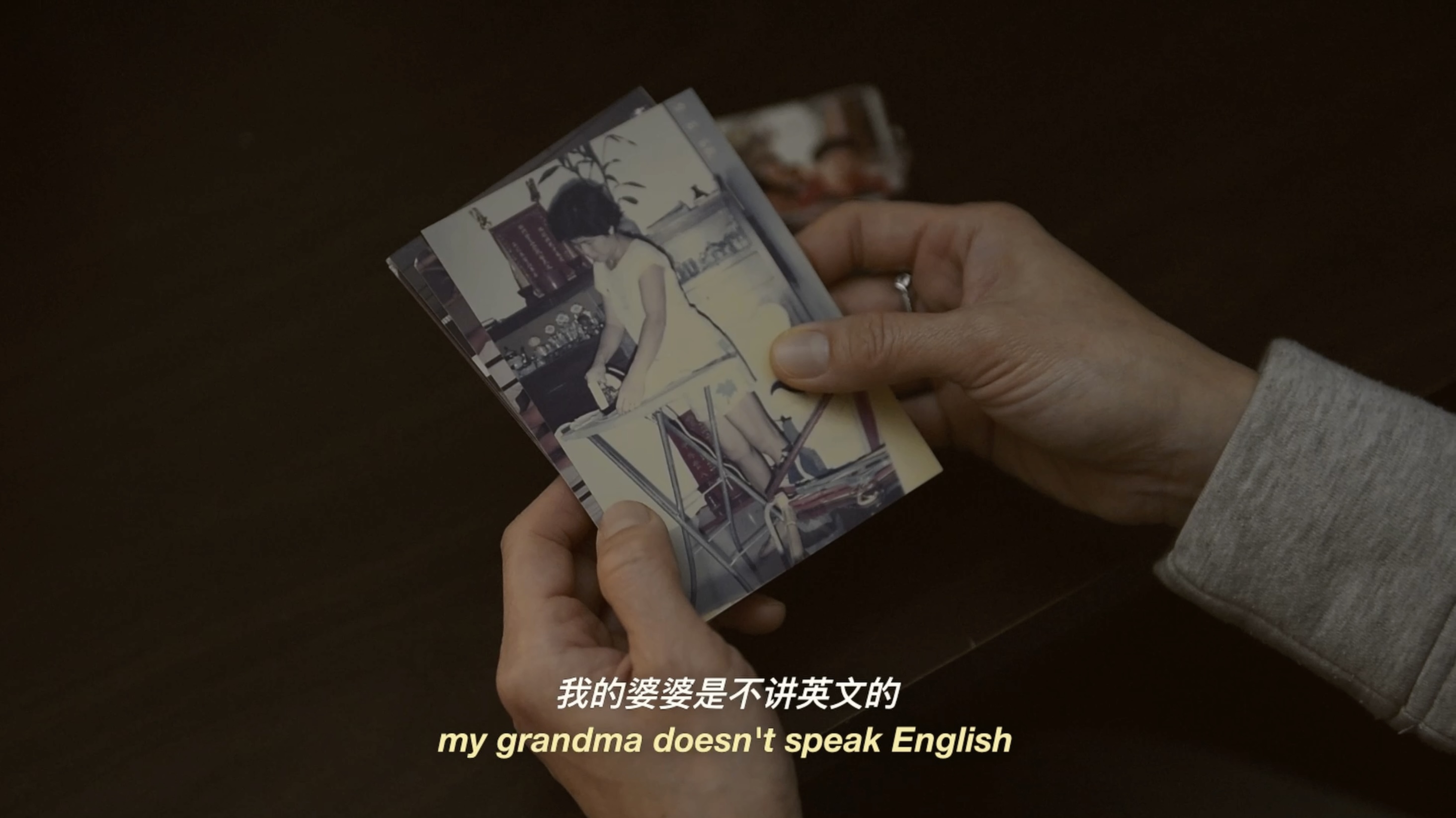

Nalinie See and I largely agree on points regarding Yong’s her name, an anthology (2024), but arrived at radically different conclusions. See states her angst at the fact that Yong describes her ah zo’s (great-grandmother's) names only in terms of her relationship with men, thereby categorising her only insofar as she exists within a patriarchal hierarchy. Superficially, this argument holds ground, since the narrator of the video, ostensibly Yong herself, states that her ah zo’s name (originally 张引治 (zhang Yin Zhi)), is pronounced in Hokkien to sound like “to attract or welcome brothers,” describing her parents’ desire for successive male children, while she later assumed the moniker 彭秀贤 (Peng Xiu Xian), having married into her husband’s family. Critically however, the voice-over is accompanied by intimate closeup shots of Chinese calligraphy, including of her ah zo’s name and family photographs. While the act of naming, writing/inscribing and photography all presuppose permanence and categorisation, by articulating objects within prevailing systems, Yong instead displays them in moments of flux—dissolving their associated hierarchies. This is most explicit in two places at the end of the video in which calligraphy and names collide. In the first instance, Yong writes her ah zo’s old name, Yin Zhi, and the name Peng Yu Zhi (彭玉治) in two separate columns. Since Peng Yu Zhi was another member of the Peng family, with a similar forename to Yong’s ah zo, the latter was forced to change her first name as well as surname upon marriage. Critically, slippage is introduced into the scene by the fact that Yong crosses her ah zo’s former name out, and instead sandwiches her new name above and below the old. This is only amplified by the next shot, as Yong uses water to again write the first iteration of her ah zo’s name, only for it to dry and disappear, before writing over it again with her new name. Hence, in both instances both the act of writing, as well as calligraphy are ridden with ambivalence, through crossing out or vanishing. Hence, even while Yong is presenting her ah zo in relation to men, the ambivalence introduces a moment of slippage and indeterminacy, utterly undermining those self-same categorical structures she describes. Where See sees this as a fault, I would argue that it is the power of the work.

![]()

Pippini Niamh, Come to the Table

Printmaking occupies a unique niche in the history of art. The delightfully strange effect of printmaking, combined with its easy reproducibility, has led to its use in protest and to disseminate information. It is in this unique social history that Niamh situates her practice. Composed of two separate works, Niamh’s contributions to Hatched consist of a large black and white print, alongside the original woodblock which produced it. This is a quiet and yet considered inversion of printmaking practices, where too often the woodblock matrix is treated as a by-product. Niamh embraces the visibility of a creative process and celebrates the processual history of her prints. Furthermore, Niamh refutes the traditional wooden block by carving into the surface of a found wooden table instead of a discardable cube. Together, the print and the found-table-turned-matrix leaves a memorable image. Two chairs flank the table, one slightly ajar and inviting viewers to sit. With the work at the table is a question left unanswered. The print is gorgeous, detailing an overflowing banquet inscribed with the opening of the Lord’s Prayer ‘Give us today our daily bread.’ The abundant reference to food and other text swirling over the prints speaks to the vast question of global food equality that pervades our contemporary age. Altogether, a stunning reinvention of a popular medium—Niamh offers an engaging and meaningful contribution to Hatched.

![]()

Silki Wong, Grip

Grip floods me with a rush of sweet and arbitrary memories. In its wrinkled fabric I encountered the comforting banality of my grandmother’s apartment, where most of my early childhood was spent. I forgot, until seeing this work, the amber beads she kept on her dresser but never wore, and the parsley she grew on her balcony, sundrenched in its terracotta pot. Perhaps it is the soft colours that drew me back to this long-ago space of safety. Banners of pale periwinkle, soft sage, and inviting indigo float cloudlike from wooden poles. Hanging both upwards and downwards they are unmoved by the hurry of wind or gravity, giving them the kind of fond aloofness that one encounters in practiced daydreamers. It is in this quiet way that Silki Wong’s unassuming pastels dissolve thresholds of forgetfulness. Seemingly free of the demands of a bustling world, they become gently tethered reference points for well-worn comforts passed. I feel sure that where I meet again worn green sofas and tins of cross-stitch thread, others beside me waft through their own sacred collections of chocolate wrapper treasures. Wong’s coloured fabric rectangles shine through their snowy veils, illuminated as the stained glass shadows cast by spring leaves in the morning sun. Beautiful and wilted, the work is lit from within by the warmest golden threads that draw together eight billion everydays.

Images courtesy of the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. Documentation photos by Rebecca Mansell.

— Sam Beard

Germaine Chan, It’s the Revelation

The jumble of exposed beams, air vents, and modern skylights in PICA’s Forrest Chase venue for Hatched 2025 unexpectedly elevated the annual graduate show. Finally, young artists were placed in a room that reflected the world their generation experiences: gritty, exposed and over-engineered. The context of this fresh venue gave the works greater relevance and timeliness, even though overall there was a strong material and conceptual adherence to the previous iterations of the exhibition—after all, the arts students may change, but the art educations they receive year after year primarily remain the same. One surprising development was the selection of a contemporary painting from UWA, whose Hatched contributions in recent years have evidenced a preference for students embracing less-traditional mediums (in contrast with Curtin, which routinely champions its graduating painters). UWA student and mixed media artist Germaine Chan’s contribution to Hatched, It’s the Revelation, revives historical religious painting for a contemporary context. Across her panoramic scenes, Chan’s assorted fragments of morally dubious stick-figures in ugly, human gesticulations offer a discursive reflection on contemporary inter-personal entanglements. But Chan’s genius is not in the story she tells. The real highlight of It’s the Revelation is that despite sharing with almost every other work at Hatched the feature of visually ambiguous composition, it engages this contemporary convention without compromising Chan’s idiosyncratic expression and singular artistic identity. It is this kind of artistic innovation, of using ubiquitous and stale tools to solidify one’s distinctive artistic identity, that sees Chan carving out a space for herself within—what usually feels like—a cyclical contemporary artworld. Chan’s repackaging of a ubiquitous way of working resonates with Hatched 2025, which is itself an unironic attempt to restyle the old, improving it, whilst bypassing the struggle of starting from scratch. These innovations prove that consistency does not require conformity and that Hatched may still have more to give us.

— Maraya Takoniatis

Litia Roko, 500mL/point

In today’s world, it’s a Sisyphean task to locate an artist who hasn’t been affected by the rise of generative artificial intelligence. A society already inundated with a crippling inability to engage in arts, now believes that meaningful images can be produced by an algorithm regurgitating probabilistic pixels and slop. It is no surprise a collective exhibition of recently graduated and emerging artists would grapple with this existential challenge. Litia Roko’s work 500 mL/point satirises this looming challenge to art practices by presenting her own cost benefit analysis of using AI. The name itself refers to the drastic water usage AI servers require to prevent themselves from combusting. The most resonant area of her video was the open criticism of the Living Museum App. This supposedly pedagogical resource claims to use AI to bring objects from the British Museum to life. The ethical authority of western programs—notorious for their wealth of stolen heritage—is already obviously problematic, yet Roko’s video intensifies the distressing qualities of rampant AI, reflecting its true scale. She draws attention to the ways that algorithms privilege the information they have been fed, and how this can be weaponised to produce narratives that obscure and mystify the truth. For instance, in 500mL/point a Moai head claims, “I love it here,” though of course it can only speak with what data it has been fed. By so openly confronting the issues that arise when artistic practice melds with generative machinery, Roko’s work leaves any viewer more assured of the absolute inherent and indispensable worth of the human element in artistic and academic practices.

— Riley Landau

Nicole Goode, Linger (grind rail) and Linger (break ramp)

Nicole Goode’s unsettling works—that is, works of unsettling—speak, wordlessly, of unbecoming. Set in negative space, the two-part performance is characterised by bared underbelly, exposed neck, and implied promises unfulfilled. It is in its “un”s, its negations, that the work becomes most concrete; the artist’s untimely body, graceful and irregular in its slowness, is less of a focal point than the disruptions that its presence creates. Linger (grind rail), Goode’s 60 minute movement performance (enacted on opening night), offered an eerie screen-to-life mirroring of Linger (break ramp), a 65-minute single-channel colour video that flickers projected from floor to ceiling upon the entry wall of PICA’s temporary warehouse abode. The live performance saw Goode entangle themselves carefully around and through the work’s metallic namesake. The steady delicateness of the artist’s extended limbs and arched frame gave the impression that Goode was supported by thickened honey. Goode’s subversive employment of skating equipment, a particularly austere steel frame exposed here and there under peeling cobalt paint, created a site of contestation. This unexpected mode of relating rendered sharply the lack of bodies and movements one anticipated. Through absence and aversion, Goode prompts the consideration of patterns of exclusion in a masculine-coded space. The discomfort afforded by Goode’s displacement was enhanced by a breakdown of typically contractual audience/performer relations. Subverting developmental logic, and reaching towards viewers with an almost unblinking gaze, Goode’s durational piece lived in the margins of social intelligibility. Disruption, however, was not manifested in distance. The artist’s bodily presence throughout Linger (grind rail) emphasised, with weighted physicality, the vulnerability implicit in “resisting expectations of movement and progress,” instilling the performance with tenderness. Softness is central, too. In Linger (break ramp), the artist tumbles down a large skate ramp (in what began as excruciatingly slow motion, until I settled into this new rhythm about ten minutes in). Goode’s performance borrows from skateboarders’ failures: the angular contortion of limbs and twisting of spines, wrapping each progression in fluidity and care. Even so, viewership is not an entirely peaceful experience. For at the heels of each gentle gesture snaps violence not yet rested into tangible form. Just as gravity seems to recognise it is robbed of crunched bone and split skin, so too is violence evoked by the slanted stares, dinged BMX bells, and chuckling leers of teenagers passing through the video’s frame. Imitation silver chains and hoodies emblazoned, like the park, with text bursting into spearheads where serifs should be, are unsettled by this quiet intervention. Goode’s temporality-warping acts of queering prompt consideration of alternative ways of being and moving within this ‘public’ space.

— Jess van Heerden

Grace Yong, 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology)

I can’t speak for everyone, but as a Southeast Asian woman raised in Western culture, I’ve often found myself in fascinating conversations with friends about the tradition of women taking their partner’s surname. Some of us imagine keeping our birth names, others consider hyphenation, and a fair few embrace the tradition. Grace Yong’s her name, an anthology, shown at this year’s Hatched, feels like an invitation to extend those conversations through a different cultural and historical lens. Gentle and introspective, the work is elegantly and thoughtfully composed, unfolding layers of meaning that invite the viewer to pause and reflect on the art of names. The video traces the way names carry lineage, tradition, and quiet currents of power, shaped by the push and pull of matriarchal and patriarchal customs. Layering image and text, it opens space for viewers to consider not just what a name means, but how it binds us to ancestry, shapes our sense of gender, and reflects the expectations of the world we move through. In earnest, I had low expectations for this video because it initially seemed overly direct and plain; yet, there is a quiet persistence to it. It’s the kind of work that lingers in your mind, unfolding its depth slowly, like a book you return to repeatedly, noticing something new each time. At certain moments, I found myself quietly enraged and confused, particularly when Yong uses phrases like “when she became a daughter” or “when she became a wife” to describe her great-grandmother’s name change. These words highlight a disheartening reality that as women, our surnames—our link to family and legacy—rarely stay with us or pass down through the maternal line. At birth, we are our father’s daughters; in marriage, our husbands’ wives; and the children we bear carry his name. Perhaps some of my frustration mirrors that of another Hatched nominee, whose work reflects on the biological truth that a woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have, formed while she is still a fetus inside her mother’s womb. In carrying a child, she also carries the potential for the eggs of her future grandchildren. But I digress. Watching Yong’s work, I felt a mixture of hurt, confusion, and indignation, torn between respect for tradition and frustration with a social practice that often feels arbitrary. However, I should clarify that I am not here to dictate whether anyone should keep, change, or hyphenate their surname; it is a deeply personal choice and one I remain uncertain of myself. Still, the work leaves you with a lingering awareness of how deeply names shape identity, lineage, and those quiet, often invisible, structures of gender in our lives.

— Nalinie See

Grace Yong, 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology)

Nalinie See and I largely agree on points regarding Yong’s her name, an anthology (2024), but arrived at radically different conclusions. See states her angst at the fact that Yong describes her ah zo’s (great-grandmother's) names only in terms of her relationship with men, thereby categorising her only insofar as she exists within a patriarchal hierarchy. Superficially, this argument holds ground, since the narrator of the video, ostensibly Yong herself, states that her ah zo’s name (originally 张引治 (zhang Yin Zhi)), is pronounced in Hokkien to sound like “to attract or welcome brothers,” describing her parents’ desire for successive male children, while she later assumed the moniker 彭秀贤 (Peng Xiu Xian), having married into her husband’s family. Critically however, the voice-over is accompanied by intimate closeup shots of Chinese calligraphy, including of her ah zo’s name and family photographs. While the act of naming, writing/inscribing and photography all presuppose permanence and categorisation, by articulating objects within prevailing systems, Yong instead displays them in moments of flux—dissolving their associated hierarchies. This is most explicit in two places at the end of the video in which calligraphy and names collide. In the first instance, Yong writes her ah zo’s old name, Yin Zhi, and the name Peng Yu Zhi (彭玉治) in two separate columns. Since Peng Yu Zhi was another member of the Peng family, with a similar forename to Yong’s ah zo, the latter was forced to change her first name as well as surname upon marriage. Critically, slippage is introduced into the scene by the fact that Yong crosses her ah zo’s former name out, and instead sandwiches her new name above and below the old. This is only amplified by the next shot, as Yong uses water to again write the first iteration of her ah zo’s name, only for it to dry and disappear, before writing over it again with her new name. Hence, in both instances both the act of writing, as well as calligraphy are ridden with ambivalence, through crossing out or vanishing. Hence, even while Yong is presenting her ah zo in relation to men, the ambivalence introduces a moment of slippage and indeterminacy, utterly undermining those self-same categorical structures she describes. Where See sees this as a fault, I would argue that it is the power of the work.

— Kye Fisher

Pippini Niamh, Come to the Table

Printmaking occupies a unique niche in the history of art. The delightfully strange effect of printmaking, combined with its easy reproducibility, has led to its use in protest and to disseminate information. It is in this unique social history that Niamh situates her practice. Composed of two separate works, Niamh’s contributions to Hatched consist of a large black and white print, alongside the original woodblock which produced it. This is a quiet and yet considered inversion of printmaking practices, where too often the woodblock matrix is treated as a by-product. Niamh embraces the visibility of a creative process and celebrates the processual history of her prints. Furthermore, Niamh refutes the traditional wooden block by carving into the surface of a found wooden table instead of a discardable cube. Together, the print and the found-table-turned-matrix leaves a memorable image. Two chairs flank the table, one slightly ajar and inviting viewers to sit. With the work at the table is a question left unanswered. The print is gorgeous, detailing an overflowing banquet inscribed with the opening of the Lord’s Prayer ‘Give us today our daily bread.’ The abundant reference to food and other text swirling over the prints speaks to the vast question of global food equality that pervades our contemporary age. Altogether, a stunning reinvention of a popular medium—Niamh offers an engaging and meaningful contribution to Hatched.

— Riley Landau

Silki Wong, Grip

Grip floods me with a rush of sweet and arbitrary memories. In its wrinkled fabric I encountered the comforting banality of my grandmother’s apartment, where most of my early childhood was spent. I forgot, until seeing this work, the amber beads she kept on her dresser but never wore, and the parsley she grew on her balcony, sundrenched in its terracotta pot. Perhaps it is the soft colours that drew me back to this long-ago space of safety. Banners of pale periwinkle, soft sage, and inviting indigo float cloudlike from wooden poles. Hanging both upwards and downwards they are unmoved by the hurry of wind or gravity, giving them the kind of fond aloofness that one encounters in practiced daydreamers. It is in this quiet way that Silki Wong’s unassuming pastels dissolve thresholds of forgetfulness. Seemingly free of the demands of a bustling world, they become gently tethered reference points for well-worn comforts passed. I feel sure that where I meet again worn green sofas and tins of cross-stitch thread, others beside me waft through their own sacred collections of chocolate wrapper treasures. Wong’s coloured fabric rectangles shine through their snowy veils, illuminated as the stained glass shadows cast by spring leaves in the morning sun. Beautiful and wilted, the work is lit from within by the warmest golden threads that draw together eight billion everydays.

— Jess van Heerden

Images courtesy of the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. Documentation photos by Rebecca Mansell.