Patrick Doherty’s artworks look as if he took the classifications from Jorge Luis Borges’s Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge and literally depicted them. Doherty’s mishmash paintings are worlds inhabited by those belonging to the Emperor; trained ones; suckling pigs; embalmed ones; stray dogs; those that tremble as if they were mad; those drawn with a very fine camel hair brush; those that have just broken the vase; those that from afar look like flies and the whole hilarious list Et Cetera.[1] Others too, have noted the violent and biting nightmare-like qualities to his work.[2]

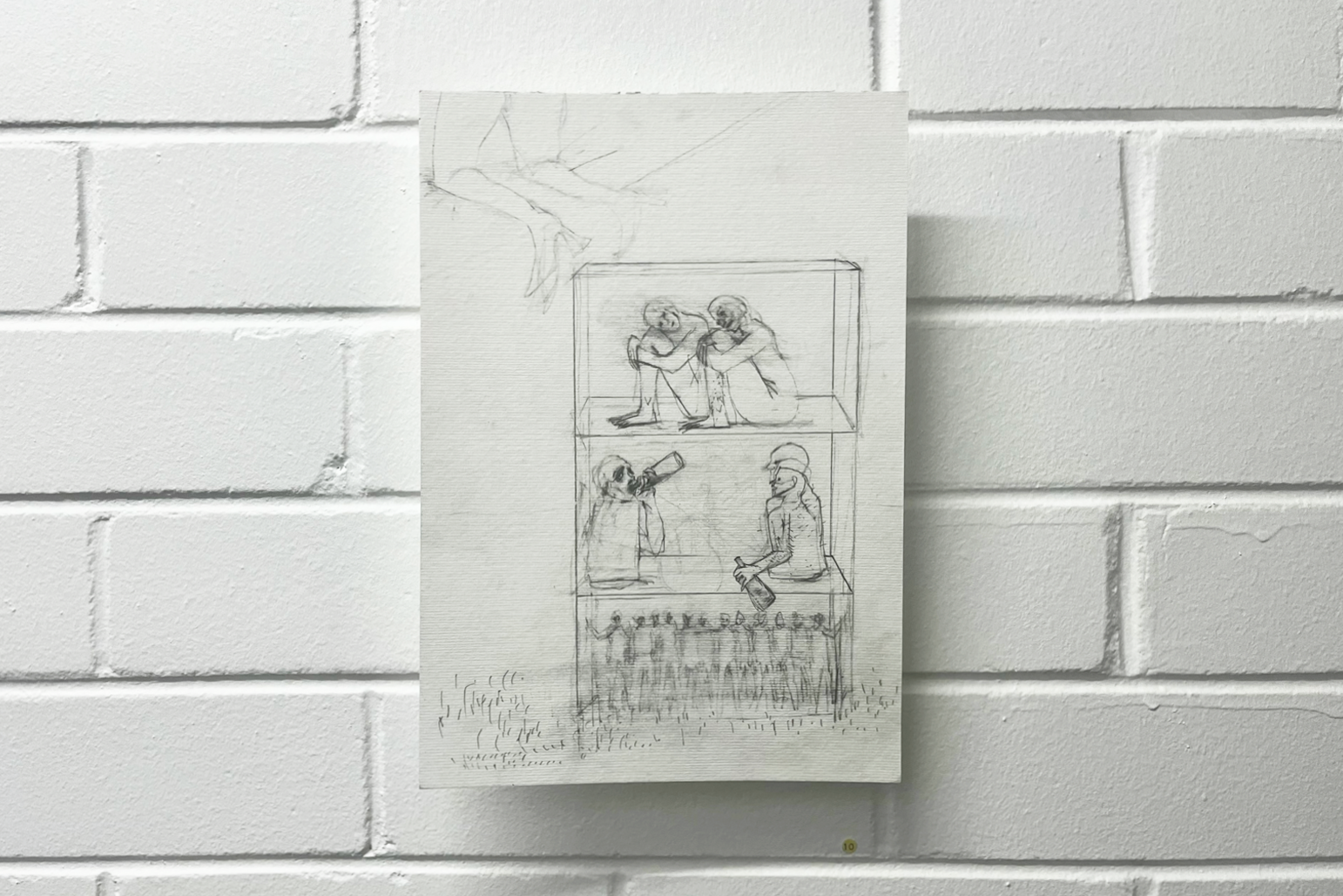

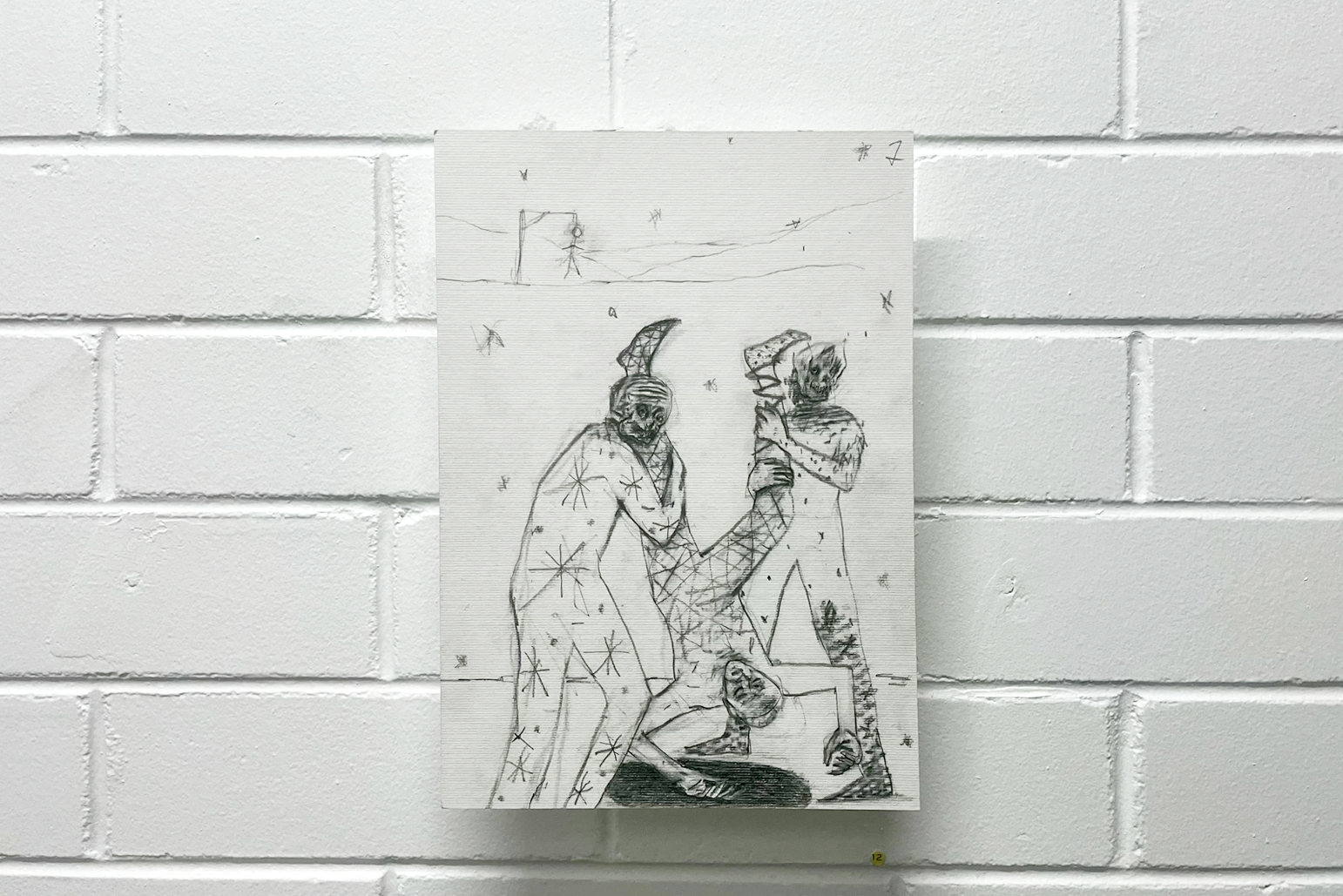

Nightmares may recur, but it has been ten years since Perth’s enfant terrible and graf rat, Patrick Doherty had a solo exhibition. Currently on display at Chinoiserie Fine Art are three paintings and 23 graphite drawings.

Before I talk about this show I want to talk about its title: INFELICITOUS PREDILECTION. It’s all caps: hissing assonance, slipping sibilance, a spitting plosive at the sixth syllable, the tone of disapproval almost onomatopoeic. Infelicitous predilection. Infelicitous does not mean “unhappy” as I first mistakenly thought: whilst felicitous can mean “happy”, “pleasant”, or “delightful”, the in- prefix is not its inverse. Our word, Doherty’s word, INFELICITOUS signifies “inappropriate”, even “unseemly” or “perverse”. These of course play on the other meaning of felicitous, not as “happy” but as “apt” or “satisfactory”. A predilection is a preference, a particularity, a penchant. The loaded phrasing sets up some kind of moral landscape to confront as much as the images themselves do.

In distorted acrylics, oils, and spray paints, Doherty depicts the following, aberrant and fascinating: groupings of grotesque, flesh biting, cum guzzling figures frozen in duos and trios; most wearing clown make-up, face-paint, ruffles, party hats, and costumes; others wearing masks and masking in jester hats (cockscombs), hoods, headdresses, and halos. Variously stabbing each other, heads exploding, juggling, playing instruments, riding unicycles. Thrusting cocks. Daggers and dirty feet. Devils retreating into shadows. Demons clawing skin, drawing blood, gnawing limbs. Colours and forms that wither and recede. Martyrdom and masturbation. Instrumental fanfare. A hobby horse and headstones. The suspense is enthralling. The specificities and strangeness that these aesthetics traffic in are contained within three paintings with intensely personal titles: I Forget Every Lesson Learned From Every Mistake; But, I Remember the Lyrics to Every Song I’ve Ever Cried To; and That Disappoints Me :) .

There is some sort of art world here—portraits hung on walls within paintings, figures or half figures on plinths. There are approximations of classical architecture: columns, busts, friezes. Figures put decapitated heads in bags or give head. The ways that these bodies are depicted almost always features enlarged and engorged limbs and hands, elongated features, with their arrangements suggesting a hieratic or playful scale. The hands are always outstretched, anguished, grasping, clutching, holding, covering, restraining, or pointing. Almost every fingernail is a talon.

More on these works later, first a story. Half a decade prior to meeting Doherty in person, I saw a beguiling painting of him like some reverse (perverse?) blind date: here is the painted image, here the man.

Said portrait of Doherty was by artist Kim Hyunji, seen by me half a decade ago at the 2018 Lester Prize at AGWA, in the pre-COVID era (then called The Black Swan Prize). I was volunteering on the desk, and whilst most of the other volunteers were upstairs to hear the speeches on opening night, I stayed in the downstairs gallery. Someone had to. Hyunji is a Melbourne-based artist who has been heavily involved in the fashion/runway scene and, like Doherty, had studied at Curtin and lived in Perth.

Hyunji’s portrait of Doherty was interesting for two reasons: it was a full-length, front-facing work painted on a clear acrylic sheet and was suspended in front of a mirror the same size. It depicted a dead Doherty as Christ or a Christlike figure; nude but for a loincloth (which was actually a nappy); sinew and bruises and tattoos on display; a doubling of his visage’s shadow suggesting a halo or heavenly ascension. Hyunji painted Doherty’s tattoos in various stages of legibility, with many scribbled, hasty, and wobbly. The phrases “wholly fucked” and “fixin’ to die” inked across his belly were clearest. Doherty the wholly, holey, holy lord. Most intriguingly, the label then said something about Doherty being a “well-known figure” in the art world, with words like delinquent, tomfoolery, outcast, hardship, and antics characterising this representation.

In 2018, I had no clue who Pat Doherty was. Even then though, the irony of his moniker’s similarity to none other than Pete Doherty was not lost on me. Call it a convenient coincidence or nominative determinism, that the other tattooed menace, fashion idol, “bad boy”, talented artist who was always stumbling, heavy-lidded, wasted, in trouble, shared so many letters. The idols of the early 2000s marketed us tattered designer labels and heroin chic; the tabloids that represented them dosed out these candid snaps with revulsion and admiration in equal measures.

The two Dohertys and Pat’s work makes me wonder if we are taught to automatically reject a preference for the perverse or inappropriate; tolerate it only in the name of higher art or talent; scoff in dismay; or be intrigued enough to spend money on a paper rag explaining why someone or something is controversial. Does outlaying coin absolve judgement? Can repulsion and attraction only survive through the catalyst of morbid fascination? Why is controversy thought of as something to be avoided or overcome, a vice in and of itself?

Decorative backdrop patterns of blood or teardrop shapes that clash against coloured light-up disco dancefloors would suggest that you can have it all in one. Of course, there is Shakespeare; these violent delights have violent ends. We see swathes and beams of light, skewiff stars, lightning strikes. Polka dots and checks abound, giving all scenes a harlequin-like quality. There are pointy shoes, just like the ones fashion-art-music scene boy Noel Fielding paints and draws; and Klan-like hoods where the obvious comparison is to Phillip Guston. The compositions are careful and balanced. The whole thing could be a cartoon for a Medieval or Renaissance tapestry. Doherty gives strong Mannerist associations thematically and aesthetically. The works drip with religious allusions and symbols: lilies, a red apple, snakes, and a goat/Pan-like figure, the eternal symbol of sexual deviance.

Finally, there is a whole lot of SLUDGE (Salivation, Lacrimation, Urination, Defecation, Gastrointestinal distress, and Emesis) as if the scenes were possessed by an invisible poison. Whilst you might think the whole thing would be a shitmess (and we certainly see a few of those), the execution, style, achievement, and ideas behind these works are fucking brilliant. They are intense but not stifling. Rhythmic but never predictable.

These paintings sit within the “inside out world” of the Carnivalesque: theorised by Bahktin as at once clever and stupid; sacred and profane; a celebration and decrial of the bodily based, where one can be crowned and uncrowned; a meditation on the latent sides of human nature.[3] These works are about love and sanity. Theories of the Carnivalesque often emphasise its dissolution of class. Doherty, with the use of Mise en abyme—literally “placement in abyss”, of placing an image recursively within itself—points class out. Academic Barbara Brownie notes on clowns and costume, the dress originated from paupers: only wealthy classes could afford tailoring, and the poor were forced to wear whatever they could find. The mishmash of whatever was found and fit resulted in the clown’s signature incoordination. Furthermore, she notes that the clown’s makeup makes emotions unreadable and unpredictable.[4] Despite the fact that core elements of the look became chic (i.e., think baggy hip hop street style), the clown himself never became fashionable. Adding layers to this reading, Doherty himself has collaborated with Australian high fashion label Romance Was Born. Such fecund doublings in theory and image are compelling and caustic. Hypnotic and dazzling, Doherty works his way through fleshiness, thorniness, ridiculousness. Menacing and playful, these paintings are troubled and troubling.

As Christopher Crouch’s brilliant essay for the show notes,

An obvious comparison to Doherty is Hieronymus Bosch, but where Bosch’s depictions of hybrid creatures and violence had a moralising role (inciting dread and confusion, thus one must avoid evil, turn away from hell, repent for the apocalypse, etc.), Doherty’s works achieve something else. The mix of pathos and recalcitrance that both produces these paintings and is produced by them is enthralling.

It is a personal, complex struggle that generates these turbulent, uncompromising, and thorny paintings. Patrick Doherty’s artistic reputation has preceded him for a range of reasons. My choice to introduce him in this text as enfant terrible was deliberate. This is what people in the art world are comfortable knowing him to be. But looking at his works reminds us such terms are merely ways of measuring the degree to which a person violates assumptions of normativity. Sidestepping controversy, Doherty in INFELICITOUS PREDILECTION invokes a reading of violence, class, desire that is closer to the Foucauldian:

And finally, of the other system mentioned, Borges’s Celestial Emporium: the writer invented this taxonomy as a way to expose the arbitrariness of any attempts to universally categorise the world, i.e., in art or language. Parallel to him, Doherty’s imagery is as difficult, spasmodic, and effulgent. He reminds us that the human condition is an eternal “predicament, not a problem and solution”.[6] And the bad boy’s “Wholly fucked” tattoo? He got it covered up at his mum’s request.

Patrick Doherty, Infelicitous Predilection, 17 December 2023 - 19 January 2024. Chinoiserie Fine Art.

Footnotes:

1. Jorge Luis Borges, “Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge” in The Analytical Language of John Wilkins, 1942. For elaboration on Borges’s list, see Aden Rolfe, “The Heavenly Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge: Classification, Categorisation & Poetics,” Master’s Dissertation, Western Sydney University, 2017.

2. Thalia Sanders, “Hypergamy @ Studio281 review,” Rotunda Media, 2015, https://rotundamedia.wordpress.com/2015/12/21/review-hypergamy-studio281/

3. Renate Lachmann, “Bakhtin and Carnival: Culture as Counter-Culture” in Cultural Critique, No. 11 (Winter, 1988-1989), University of Minnesota Press.

4. Barbara Brownie, “Clowns and class” in Costume & Culture, 2016. https://barbarabrownie.wordpress.com/2014/07/23/clowns_and_class/

5. Stephanie Batters, “Care of the Self and the Will to Freedom: Michel Foucault, Critique and Ethics,” Honours dissertation, 2011.

6. Shelby Sheppard, “The Merits of Controversy” in Journal of Educational Controversy, Western Washington University, 2006. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=jec

Photographs of Patrick Doherty’s Infelicitous Predilection at Chinoiserie Fine Art by Dispatch Review.

Nightmares may recur, but it has been ten years since Perth’s enfant terrible and graf rat, Patrick Doherty had a solo exhibition. Currently on display at Chinoiserie Fine Art are three paintings and 23 graphite drawings.

Before I talk about this show I want to talk about its title: INFELICITOUS PREDILECTION. It’s all caps: hissing assonance, slipping sibilance, a spitting plosive at the sixth syllable, the tone of disapproval almost onomatopoeic. Infelicitous predilection. Infelicitous does not mean “unhappy” as I first mistakenly thought: whilst felicitous can mean “happy”, “pleasant”, or “delightful”, the in- prefix is not its inverse. Our word, Doherty’s word, INFELICITOUS signifies “inappropriate”, even “unseemly” or “perverse”. These of course play on the other meaning of felicitous, not as “happy” but as “apt” or “satisfactory”. A predilection is a preference, a particularity, a penchant. The loaded phrasing sets up some kind of moral landscape to confront as much as the images themselves do.

In distorted acrylics, oils, and spray paints, Doherty depicts the following, aberrant and fascinating: groupings of grotesque, flesh biting, cum guzzling figures frozen in duos and trios; most wearing clown make-up, face-paint, ruffles, party hats, and costumes; others wearing masks and masking in jester hats (cockscombs), hoods, headdresses, and halos. Variously stabbing each other, heads exploding, juggling, playing instruments, riding unicycles. Thrusting cocks. Daggers and dirty feet. Devils retreating into shadows. Demons clawing skin, drawing blood, gnawing limbs. Colours and forms that wither and recede. Martyrdom and masturbation. Instrumental fanfare. A hobby horse and headstones. The suspense is enthralling. The specificities and strangeness that these aesthetics traffic in are contained within three paintings with intensely personal titles: I Forget Every Lesson Learned From Every Mistake; But, I Remember the Lyrics to Every Song I’ve Ever Cried To; and That Disappoints Me :) .

There is some sort of art world here—portraits hung on walls within paintings, figures or half figures on plinths. There are approximations of classical architecture: columns, busts, friezes. Figures put decapitated heads in bags or give head. The ways that these bodies are depicted almost always features enlarged and engorged limbs and hands, elongated features, with their arrangements suggesting a hieratic or playful scale. The hands are always outstretched, anguished, grasping, clutching, holding, covering, restraining, or pointing. Almost every fingernail is a talon.

More on these works later, first a story. Half a decade prior to meeting Doherty in person, I saw a beguiling painting of him like some reverse (perverse?) blind date: here is the painted image, here the man.

Said portrait of Doherty was by artist Kim Hyunji, seen by me half a decade ago at the 2018 Lester Prize at AGWA, in the pre-COVID era (then called The Black Swan Prize). I was volunteering on the desk, and whilst most of the other volunteers were upstairs to hear the speeches on opening night, I stayed in the downstairs gallery. Someone had to. Hyunji is a Melbourne-based artist who has been heavily involved in the fashion/runway scene and, like Doherty, had studied at Curtin and lived in Perth.

Hyunji’s portrait of Doherty was interesting for two reasons: it was a full-length, front-facing work painted on a clear acrylic sheet and was suspended in front of a mirror the same size. It depicted a dead Doherty as Christ or a Christlike figure; nude but for a loincloth (which was actually a nappy); sinew and bruises and tattoos on display; a doubling of his visage’s shadow suggesting a halo or heavenly ascension. Hyunji painted Doherty’s tattoos in various stages of legibility, with many scribbled, hasty, and wobbly. The phrases “wholly fucked” and “fixin’ to die” inked across his belly were clearest. Doherty the wholly, holey, holy lord. Most intriguingly, the label then said something about Doherty being a “well-known figure” in the art world, with words like delinquent, tomfoolery, outcast, hardship, and antics characterising this representation.

In 2018, I had no clue who Pat Doherty was. Even then though, the irony of his moniker’s similarity to none other than Pete Doherty was not lost on me. Call it a convenient coincidence or nominative determinism, that the other tattooed menace, fashion idol, “bad boy”, talented artist who was always stumbling, heavy-lidded, wasted, in trouble, shared so many letters. The idols of the early 2000s marketed us tattered designer labels and heroin chic; the tabloids that represented them dosed out these candid snaps with revulsion and admiration in equal measures.

The two Dohertys and Pat’s work makes me wonder if we are taught to automatically reject a preference for the perverse or inappropriate; tolerate it only in the name of higher art or talent; scoff in dismay; or be intrigued enough to spend money on a paper rag explaining why someone or something is controversial. Does outlaying coin absolve judgement? Can repulsion and attraction only survive through the catalyst of morbid fascination? Why is controversy thought of as something to be avoided or overcome, a vice in and of itself?

Decorative backdrop patterns of blood or teardrop shapes that clash against coloured light-up disco dancefloors would suggest that you can have it all in one. Of course, there is Shakespeare; these violent delights have violent ends. We see swathes and beams of light, skewiff stars, lightning strikes. Polka dots and checks abound, giving all scenes a harlequin-like quality. There are pointy shoes, just like the ones fashion-art-music scene boy Noel Fielding paints and draws; and Klan-like hoods where the obvious comparison is to Phillip Guston. The compositions are careful and balanced. The whole thing could be a cartoon for a Medieval or Renaissance tapestry. Doherty gives strong Mannerist associations thematically and aesthetically. The works drip with religious allusions and symbols: lilies, a red apple, snakes, and a goat/Pan-like figure, the eternal symbol of sexual deviance.

Finally, there is a whole lot of SLUDGE (Salivation, Lacrimation, Urination, Defecation, Gastrointestinal distress, and Emesis) as if the scenes were possessed by an invisible poison. Whilst you might think the whole thing would be a shitmess (and we certainly see a few of those), the execution, style, achievement, and ideas behind these works are fucking brilliant. They are intense but not stifling. Rhythmic but never predictable.

These paintings sit within the “inside out world” of the Carnivalesque: theorised by Bahktin as at once clever and stupid; sacred and profane; a celebration and decrial of the bodily based, where one can be crowned and uncrowned; a meditation on the latent sides of human nature.[3] These works are about love and sanity. Theories of the Carnivalesque often emphasise its dissolution of class. Doherty, with the use of Mise en abyme—literally “placement in abyss”, of placing an image recursively within itself—points class out. Academic Barbara Brownie notes on clowns and costume, the dress originated from paupers: only wealthy classes could afford tailoring, and the poor were forced to wear whatever they could find. The mishmash of whatever was found and fit resulted in the clown’s signature incoordination. Furthermore, she notes that the clown’s makeup makes emotions unreadable and unpredictable.[4] Despite the fact that core elements of the look became chic (i.e., think baggy hip hop street style), the clown himself never became fashionable. Adding layers to this reading, Doherty himself has collaborated with Australian high fashion label Romance Was Born. Such fecund doublings in theory and image are compelling and caustic. Hypnotic and dazzling, Doherty works his way through fleshiness, thorniness, ridiculousness. Menacing and playful, these paintings are troubled and troubling.

As Christopher Crouch’s brilliant essay for the show notes,

“the awfulness of the imagery is mitigated by the characters in the paintings, however. We know they have been contracted to confront us with their bad behaviour in their stereotypical costumes, and we know the painting of violence is a very different thing from the genocide enacted by states on civilian populations. Standing in front of this fictional depiction of individually enacted violence we can ultimately switch on our understanding of Shakespearean dramatic irony, or Brechtian aesthetic alienation, secure in the knowledge that we can put our momentary existential despair at arm’s length.”

An obvious comparison to Doherty is Hieronymus Bosch, but where Bosch’s depictions of hybrid creatures and violence had a moralising role (inciting dread and confusion, thus one must avoid evil, turn away from hell, repent for the apocalypse, etc.), Doherty’s works achieve something else. The mix of pathos and recalcitrance that both produces these paintings and is produced by them is enthralling.

It is a personal, complex struggle that generates these turbulent, uncompromising, and thorny paintings. Patrick Doherty’s artistic reputation has preceded him for a range of reasons. My choice to introduce him in this text as enfant terrible was deliberate. This is what people in the art world are comfortable knowing him to be. But looking at his works reminds us such terms are merely ways of measuring the degree to which a person violates assumptions of normativity. Sidestepping controversy, Doherty in INFELICITOUS PREDILECTION invokes a reading of violence, class, desire that is closer to the Foucauldian:

“Institutions and their discursive practices are the agents by which subjects are divided, classified, and subjected to normalisation. Consider the categories of normal versus mad, normal versus criminal, normal versus pervert, normal versus poor, modern versus traditional, and developed versus underdeveloped…”[5]

And finally, of the other system mentioned, Borges’s Celestial Emporium: the writer invented this taxonomy as a way to expose the arbitrariness of any attempts to universally categorise the world, i.e., in art or language. Parallel to him, Doherty’s imagery is as difficult, spasmodic, and effulgent. He reminds us that the human condition is an eternal “predicament, not a problem and solution”.[6] And the bad boy’s “Wholly fucked” tattoo? He got it covered up at his mum’s request.

Patrick Doherty, Infelicitous Predilection, 17 December 2023 - 19 January 2024. Chinoiserie Fine Art.

Footnotes:

1. Jorge Luis Borges, “Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge” in The Analytical Language of John Wilkins, 1942. For elaboration on Borges’s list, see Aden Rolfe, “The Heavenly Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge: Classification, Categorisation & Poetics,” Master’s Dissertation, Western Sydney University, 2017.

2. Thalia Sanders, “Hypergamy @ Studio281 review,” Rotunda Media, 2015, https://rotundamedia.wordpress.com/2015/12/21/review-hypergamy-studio281/

3. Renate Lachmann, “Bakhtin and Carnival: Culture as Counter-Culture” in Cultural Critique, No. 11 (Winter, 1988-1989), University of Minnesota Press.

4. Barbara Brownie, “Clowns and class” in Costume & Culture, 2016. https://barbarabrownie.wordpress.com/2014/07/23/clowns_and_class/

5. Stephanie Batters, “Care of the Self and the Will to Freedom: Michel Foucault, Critique and Ethics,” Honours dissertation, 2011.

6. Shelby Sheppard, “The Merits of Controversy” in Journal of Educational Controversy, Western Washington University, 2006. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=jec

Photographs of Patrick Doherty’s Infelicitous Predilection at Chinoiserie Fine Art by Dispatch Review.