“... in this sense, as throughout class history, the underside of culture is blood, torture, death and horror.”

— Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, p.57.

Depending on who you ask, Judgment Day has already happened. In The Terminator universe at least, it refers to the day that the franchise’s version of Artificial Intelligence (so named Skynet) becomes self aware and starts a nuclear war on several countries. Depending on which movie you watch, this AI-pocalypse was either in 1994 or 1997 or 2005. Pinpointing the date it all went wrong IRL seems kind of redundant these days; the pendulum swings from chatbot psychosis to mass surveillance. In what Fredric Jameson might term ‘several generations of machine power and multinational capitalism’ later, we are so much more deeply fucked than he could have conceived in 1984, when he theorised postmodernity as a culture of things ending, of pastiche and ahistoricity. Or are we? Acid Utopia asks differently.

The phrase ‘Judgment Day’ for any art historian also conjures the material tradition of painting the biblical verse from Acts, where apparently God and/or Jesus will judge all of humankind on the inhabited earth, “the living and the dead.” People will either be saved or damned, deemed just or unjust, sent to heaven or hell, etc. Not unlike the ‘catastrophic or redemptive’ dialectic of the end of times-ness Jameson mentions. Also called ‘Doom paintings’ (after Doomsday), arguably the most famous version is Michelangelo’s mannerist take on The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel (painted from 1537–41).

From Doomsday to doomscrolling, our various armageddons contextualise this exhibition. The redeeming parts are more to do with the ‘Acid’ elements (aesthetically speaking) and less concerned with ‘Utopia’—although I guess making art is in itself a compensatory or utopian gesture these days. Ironic title or otherwise, Acid Utopia: Judgment Day is the second group show by Lyle Branson, Peter Carlino, Anthony Kelly and Guillermo Kramer. All have all debuted new works, made in 2025. In the small community gallery in East Vic Park, AI slop, doomscrolling, and several layers of imagistic simulacra inform and underscore both the artworks and our viewing experience. The high key colours, pristine installation and bizarre combination of artworks makes this exhibition, as a whole, rather fun, even if its component parts are depressing, frustrating and occasionally pretty scary.

The artists responded to the domestic scale of the gallery architecture, by painting and building walls in 1930s-ish colours that match the cottage’s decor and offset the works nicely. In the two rooms (‘Large Gallery’ and ‘Small Gallery’) they have intervened and personalised the viewing experience. For instance, in the Small Gallery (the first room), Kramer’s pastel work Say it ain’t so is a bright drawing that includes a racecar, vacuum cleaner, knife, two men fighting (one has the other in a chokehold), a chain, three-fingered clutching fist and some sort of coloured worm motif. It is hung on a red wall that is about the same colour as the gallery’s stained glass front door. The background of this work is brightly coloured and each subject is drawn with a border, framed within the frame. The flattened background plane and cartoon-like style make it clear that we are looking at several layers of representation, not a convincing attempt at reality. Here we have the carnivalesque in smudgy pastels—a little bit like a Pat Doherty, but without the emotional turbulence.

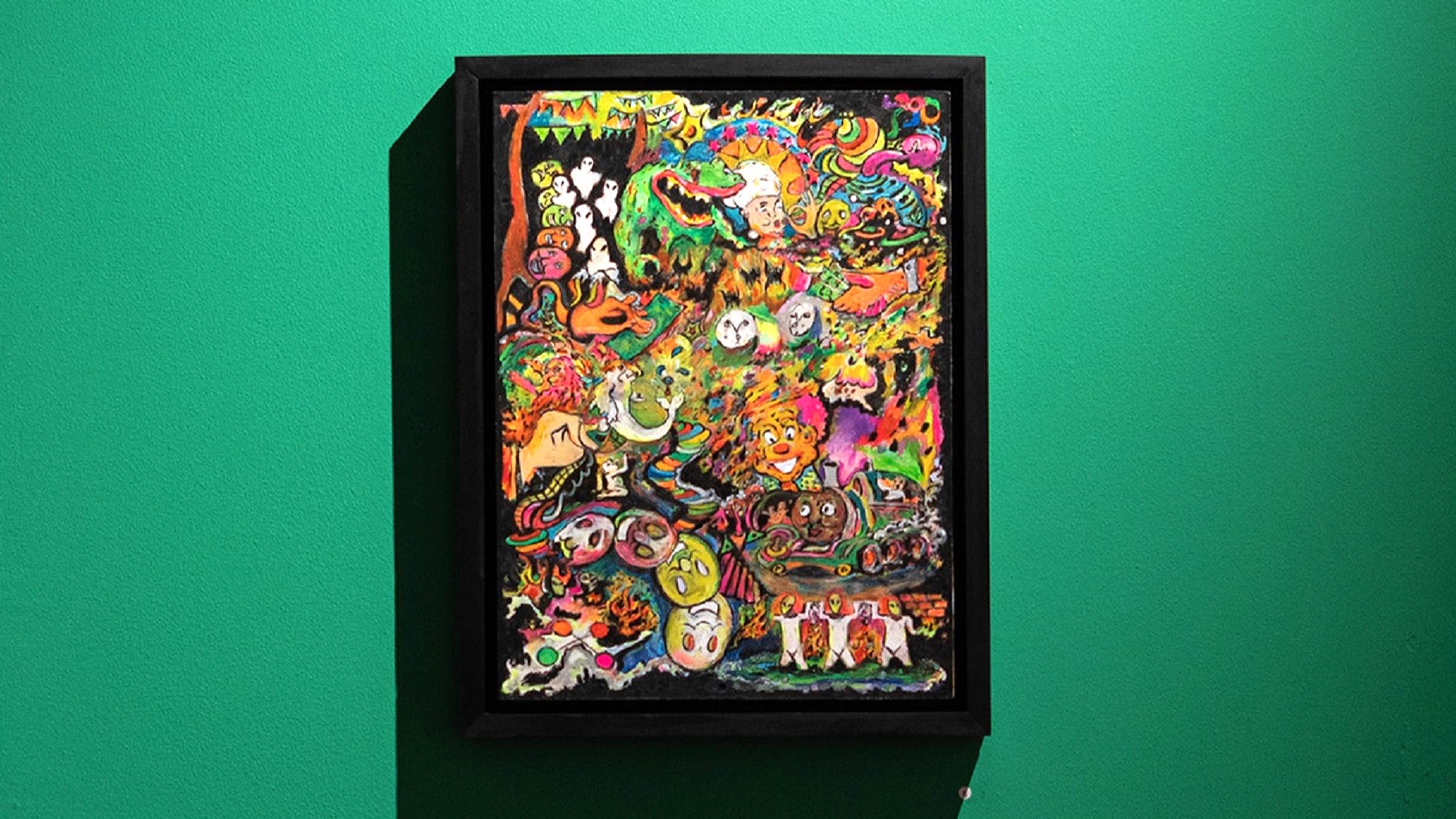

In Kramer’s Beguile, installed in the other room on a constructed green wall, I can make out an amorphous, dirty Thomas the Tank Engine-ish figure, clown faces, tick tock faces, men in alien masks, smiley faces, a hand clutching a dollar bill, a fish tail, a menacing alligator that might be a logo for something that I can’t place, ghosties, bunting flags, and what I think might be another logo of a fat smiling chef in a hat who is doing a chef’s kiss while surrounded by stars. AI is no help when I try to reverse-search these images, it just brings up heaps of shitty pastels by random artists for sale on Etsy and Bluethumb. At least Kramer’s are decently executed, if their iconographic origins appear to be indecipherable.

Back in the small gallery, Branson’s AI MP4 video work has a similar effect of discombobulation; it’s hard to tell what the discernible visuals mean, are of, or amount to, but it is surprisingly beautiful to watch. His looped video is warm, hazy, dream-like, with phosphorescent layers of colour that waft and bleed, melding into one another. It is the abstraction that makes the work appealing, compared to the (intentional) banality and upsetting content of a lot of the other imagery in the show.

In Branson’s photo collage, Warm Leatherette, we get more vacuum cleaners, tyres and wheel fragments, amazon boxes, lenses, cameras, circuit boards, robot arms and a human arm, shoving an engine and it all into a man’s face, the parts collaged and mashed together. The use of colour unites these disparate photos, some of them clearly truncated stock images, into a pleasant geometric surface pattern. This layer contrasts pleasantly with the background photo of a highly saturated, yellow- and purple-lit tree on water. Much like with Kramer’s pastels, the surface quality of Branson’s collage unites these variously sized tidbits without hierarchy, which makes it hard to ‘read’ or decipher any primacy of subject or privileging of stance from the work. Instead a sense of ambivalence emerges, which, again, I suspect is intentional. Warm Leatherette shares (or perhaps more accurately, derives) its name from the 1978 song of the same title by UK band The Normal: the placement of the amputated human arm in Branson’s composition loosely recalls the crash test dummy featured on the vinyl sleeve for The Normal’s single; the song itself having been influenced by J. G. Ballard’s 1973 novel Crash; which of course was adapted into film by David Cronenberg some 23 years later. That thought, plus the sight of Amazon boxes peeking out in the collage, is shudder worthy. The reference is clever: the emergence of New Wave/No Wave music at a time of massive technological and social upheaval is an easy parallel to draw with our current timeline of 2025, one where teenagers kill themselves to be with their AI girlfriends.

Moving into the other room, in the larger gallery space, are a series of perplexing and quite brilliant graphite drawings by Peter Carlino, who I am told is a hairdresser by trade. With titles like Boo! Barack Obama Zombie Mask, Nachos, Before the Bite, Morning Pills, plus the greyscape of graphite, the mood these works incite is flat, but aided by a delight in trying to decipher their content and subjects, and appreciating the skill of the artist’s hand. Tightly framed, these realistic works deploy incredible uses of perspective. Despite being standalone images, they seem drawn from an intensely personal or narrativised imagery, reading like an unfinished sequence or a set. The drawings are an antidote, aesthetically, to the chaotic pastiche of Branson and Kramer’s works, but, like Kelly’s, they are also deeply unsettling, employing a kind of defamiliarisation. The drawings are sometimes obvious, while others are cryptic: a noose and trapdoor, a cauliflower ominously titled Before the Bite, and my personal favourite, a hand holding a Taiyaki (‘baked sea bream’, or one of those Japanese fish desserts). The truncated limb in the composition is a subtle nod to the imagery of hands and fists in works by the two aforementioned artists.

The exhibition’s cohesion is connected by these motifs, hands, vacuum cleaners, cars, without being saccharine. Carlino’s drawing of a tiled floor titled An Emergency presents a speckled, dirty tiled texture captured in insane detail, with directional arrows and one menacing sneakered foot lurking in the corner. Its perspective appears as if you have just been punched and knocked over sideways, or maybe had a little too much, gasping for breath on the floor. Hung at eye height, it is immersive. The drawing that hangs beside it, of what I think may be a sunflower-patterned tablecloth, injects a sharp dose of nostalgia—reminding me of sitting at the family table as you contemplate your choices, hungover, the next day, but alive.

The highlight of the show is the attempt to talk to the dead, in Kelly’s work, Instrumental Transcommunication Device (Mercurian) For Use In Communication with UFO Occupants, Planetary Intelligences, the Dead, etc. Initially appearing a bit like one of those light masks for acne, Kelly’s mixed media installation is far more unsettling than UV skincare practices (notwithstanding the LED lights behind the eye holes). Featuring a desk, chair, notebook, microphone and sculpture/communication device, the work is based on the principle of EVP, or electronic voice phenomenon.

For the uninitiated, the origin story of EVP goes like this: In 1959, the Swedish painter and film producer Friedrich Jürgenson (1903-1987) was recording bird songs on a tape recorder (aptly, of the Swedish finch). Upon playing back the tape later on, Jürgenson heard what he claimed was his dead father's voice, and also, the spirit of his deceased wife calling his name. There have been many proponents since Jürgenson, with the voices also apparent on the "white noise" of certain radio bands (Kelly has employed a radio frequency in his installation, plus a notebook and recorder for capturing in pen and paper the otherworldly data.)

These voices (also known as Raudive voices) are inaudible, in principle, to human consciousness and can only be heard at a certain frequency, when played back on a tape recorder. EVP has its skeptics; but I learned at the opening that Kelly’s work was influenced by an intensely personal story the artist recounted including a comatose state and a phone randomly playing a song, bedside. I won’t reveal it here, but I will say it gave me goosebumps and sent me on a deep dive into the world of parapsychology and its fertile relationship to contemporary art practice. This fertile soil has long fuelled Kelly’s genius; in the group’s first exhibition in 2020, Acid Utopia, he made a device that purported to provide contact with UFOs. Here, we see an artist attempting to offer the actual experience of the parapsychological as art, as opposed to representing it, as the other artworks in the exhibition have done.

In terms of the ‘Acid’ aesthetic mentioned earlier, there’s a sense of current times in the exhibition, in one of Carlino’s drawings that has an Obama mask in it. However, just like the “cut-off arm” motif, and Kelly’s humanoid hexagonal coin-like sculpture, it’s not a face but a mask, and nor is it a mask but a sculpture of a mask or a drawing of a mask—an echo of something. Graphite on paper calls something into being just like radio waves. In the same sense, the radio static of EVP is able to be interpreted differently by anyone who listens to it; it has been called the sonic equivalent of seeing the man in the moon (paredolia), or perhaps can be thought of as an audible rorschach. Back to the Sistine Chapel; this idea is akin, metaphorically, to the figure of St Bartholomew in Michelangelo’s Judgment. The painted figure of St Bart holding his own flayed skin (which is also reportedly a self-portrait of Michelangelo) is disruptive to the image, a narrative impossibility that’s disconcerting and compelling. Turns out that Jürgenson was once also a papal portraitist, and painted many portraits of the Pope Paul VI. For all the doom and gloom of our current conspiracy-soaked, illiterate times, there is still the redemptive potential of the compensatory gesture, of art making, along with the elements of chance, connection, and coincidence that enrich it.

Lyle Branson, Peter Carlino, Anthony Kelly, Guillermo Kramer, Acid Utopia: Judgment Day, Kent Street Gallery, Victoria Park Centre for the Arts, 27 September – 11 October 2025.

Image credits:

Anthony Kelly, Instrumental Transcommunication Device (Mercurian) For Use In Communication with UFO Occupants, Planetary Intelligences, the Dead, etc., 2025, installation, mixed media.

Lyle Branson, Warm Leatherette, 2025, canson Photographique paper.

Guillermo Kramer, Say it ain't so, 2025, oil pastel.

Guillermo Kramer, Beguile, 2025, oil pastel.

Peter Carlino, An Emergency and Eviction, 2025, graphite on paper [the noose and arrow work].

Peter Carlino, Before the Bite and AI Bliss, 2025, graphite on paper.

All artworks 2025, courtesy the artists. Installation photos by Lyle Branson.