In late October, images depicting Republican Presidential nominee Donald Trump working at a McDonald’s—salting fries and interacting with what appeared to be thrilled customers—circulated through various social media feeds. Intended as a dig at Democrat nominee Kamala Harris’ claim that she had worked at McDonald’s in her younger years—which was used to substantiate and counterpose her relatively normal middle-class upbringing against Trump’s life of privilege—the stunt went viral for around 24 hours before dying off, as has become the norm in our clickbait dominated mediascape.

Days after an event that few cared about any longer, centrist and liberal pundits were fervent in their condemnation of the phoniness of Trump’s “shift” as a McDonald’s crew member. Guardian readers, for instance, were informed that the franchise in question had been shut down in order to facilitate the simulation of food service, with closely vetted customers playacting at surprise when encountering the Presidential hopeful at the drive through window. It was a media-event, so liberals underlined; a concocted state of affairs that was designed for media circulation and consumption only, and that would not have existed if it could not have been made viral through the channels of digital media.

However, and as Jean Baudrillard exhaustively reminded us in the 1980s and 1990s, many of the fakest aspects of contemporary consumer culture function to maintain the fiction that “out there” beyond all of the media fakery, political spin, and advertising gloss, there remains something true, real, and authentic. As Baudrillard wrote in his Simulacra and Simulation, “Disneyland exists in order to hide that it is the ‘real’ country, all of ‘real’ America that is Disneyland”. The liberal response to Trump’s McDonald’s stunt, the desperate attempt to point out that Trump’s activities are a stage-managed fraud, as opposed to the real and authentic politics apparently occurring elsewhere, is almost too perfect an illustration of Baudrillard’s point.

Interestingly, during the late 2000s and early 2010s, Trump and Baudrillard appeared to suffer a similar fate, becoming brands that existed merely for their self-reproduction. Although I never connected the two figures at the time, watching The Apprentice and reading Baudrillard in the late 2000s, I implicitly understood that both Trump and Baudrillard were viewed by many as self-parodies. The Trump and Baudrillard brands were both past it; bigger than ever, but straining for relevance, which is why, years later, it was so jarring to see the immense about-turn in their cultural impact. Indeed, riffs like the aforementioned quote from Simulacra and Simulation once seemed tired and hackneyed in a manner not dissimilar to Trump’s catchphrase “you’re fired!”—and so, after the election of Trump in 2016, it was quite a shock to find that Baudrillard’s work had gone from seemingly outlandish and metaphysical to having an almost straightforward empirical veracity, and that Trump had become one of the world’s most powerful people.

The fact that liberal critiques of Trump’s McDonald’s stunt were beside the point speaks to a longer struggle to understand Trump’s aesthetic appeal shared by centrist pundits and political operators alike. Trump’s political aesthetics have always oscillated between the banal—think of Trump’s iconic Make America Great Again hat with its oddly minimal use of the Century Schoolbook font—the grotesque—his spray tan and hair, not to mention the Trump/4chan nexus and the millions of Pepe and Groyper Trump memes—and, perhaps the most obvious, kitsch—such as Trump’s love for Rococo gold ornamentation, the paintings of Jon McNaughton, and Trump digital trading cards. For a decade now, liberals have more or less repeated Seth Meyers’ admittedly funny roast of Trump at the 2011 White House Correspondents’ dinner, and yet, the ineffectiveness of this strategy has somehow failed to provoke even a moment of self-reflection. Such attacks seem to have only reinforced Trump’s status as a normcore plutocrat, the label used by cultural theorist Jo Littler to refer to those elite insiders who have maintained an image as outsiders—as underdogs, as “one of the lads”, as inexplicably both exceedingly rich and yet relatable. Indeed, it is perhaps the case that the resilience of Trump’s aesthetic has produced a kind of monomania in the liberal unconscious, and this has inhibited Trump’s opponents in switching up their tactics. Faced with a double injury—not only the maddening fact that so many people find Trump’s banality, grotesquery, and kitschness appealing, but, even worse, they prefer him over us!—liberals appear doomed to enact the repetition compulsion of freaking out, again and again, in response to Trump’s lies, indecency, and criminality.

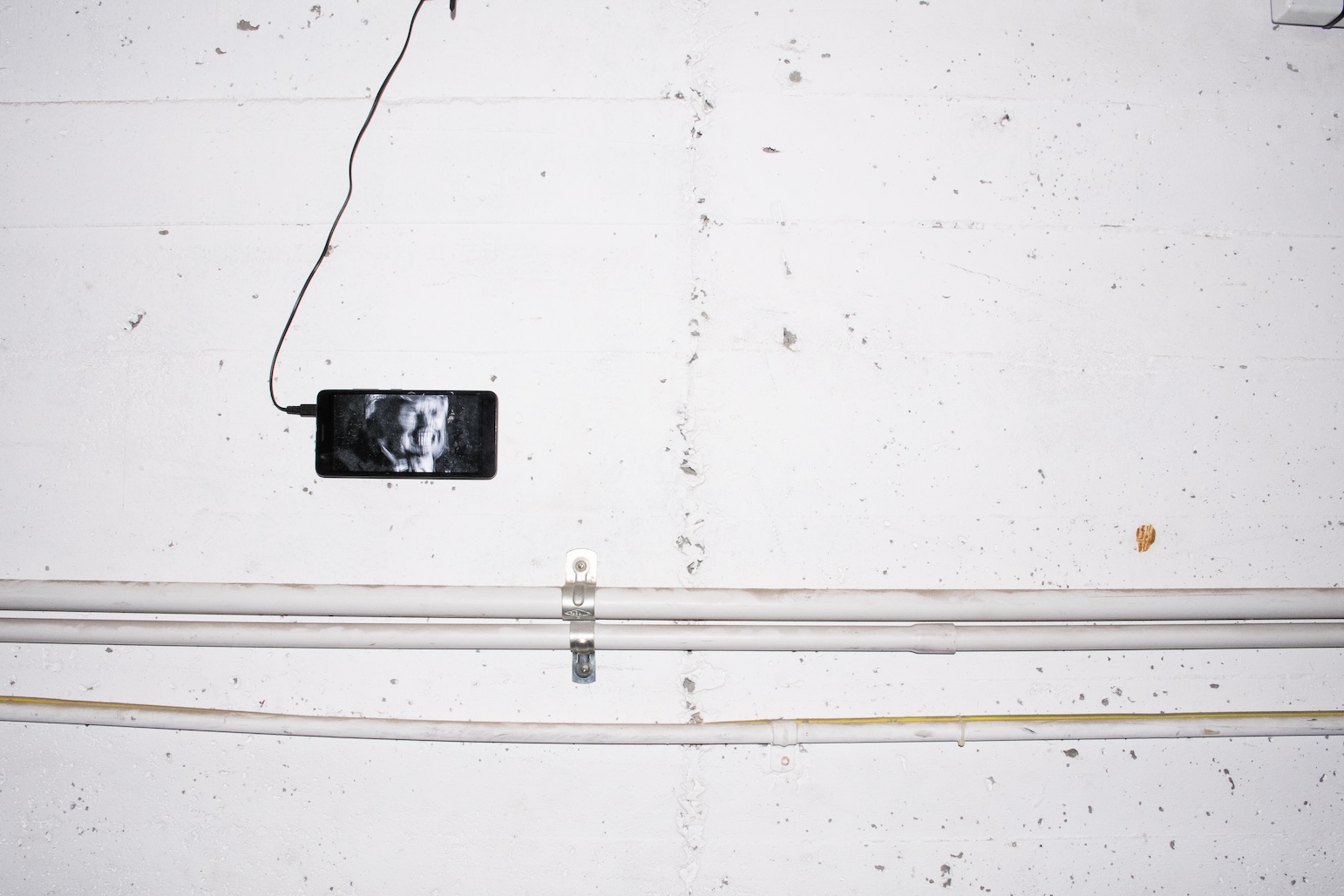

Given these preambulatory concerns, Nick FitzPatrick’s Hero Image (exhibited at Light Works) could not be timelier. As the artist describes, the show consists of ‘nine rephotographs’ or digitally reproduced digital images, in the attempt to seize, reconfigure, and disfigure ‘the mercurial and hyperreal media image of Donald Trump’. Displayed on a series of phones, tablets, and television screens in the tunnel entrance to Light Works’ courtyard, the opening night buzz of chatter echoed through the space to immediately evoke the background noise of incessant talking that has followed Trump—and that Trump has contributed to—throughout his political career. Reproducing images sourced from Al Jazeera, ABC, The Guardian, Reuters, and of course Fox News, these rephotographic works showcase various levels of intervention; some limited to shifts in hue, saturation, and blur, while others appear to have involved material interventions during image production to reveal skeletal and demonic forms.

The works in Hero Image are at their most successful when they engage in a strategy of immanent critique. Rather than attempting to satirise Trump from within an incompatible system of aesthetic and cultural values—from within, for example, the visual languages of contemporary painting and sculpture and the moral vocabulary of liberalism or a more diffuse form of progressivism—the best of Hero Image attempts to critique Trump on his own terms. For instance, all of the works present Trump to us by way of the very digital screens that facilitate his media status. While this approach risks disappointing the viewer, insofar as a critique of Trump does not arrive by way of a more obvious artistic intervention, Hero Image does not shy away from the unavoidable banality of the phone or tablet in the visual culture of contemporary life. Moreover, the works that showcase the viscerality of Trump’s form are more interesting than many conventional satirical Trump images in that they do not beautify as they lampoon. An odd feature of many of the last decade’s Trump impressions and parodies is their unwillingness to contend with just how bizarre Trump’s appearance and behaviour can be. Rather than delving into Trump’s depravity, popular artistic rebukes of Trump—whether Edel Rodriguez’s Time Magazine covers or Alec Baldwin’s SNL impressions—are so often too slick and smooth to really capture what is unsettling about Trump’s aesthetic interventions into the politics of the last decade. Whether through closeups of grimaces or jowls, Hero Image consistently succeeds in allowing a return of the repressed by unflinchingly exploring Trump’s capacity to produce abject and ambivalent images.

Ultimately, however, the most successful work in Hero Image is the least modified. The large glowing Hero Image “Big Hand” (Reuters) offers little in the way of condemnation or ridicule, but instead confronts the viewer with Trump as a diffuse exaggerated media figure. The critical strategy here feels reminiscent of Jeff Koons’ works on power, such as his 1988 sculpture Bear and Policeman. Inflating and blurring Trump’s saluting hand suggests both the menace of authoritarianism and the cartoonish innocence of a mascot. All plasma and electricity, Hero Image “Big Hand” (Reuters) reveals Trump as vast, soft, dumb, and empty, but in a way that is haunting and utterly transfixing. It is undoubtedly this standout work that captures the combination of power and stupidity, banality and violence, fun and terror that is characteristic of the libidinal investments afforded by Trump.

Ideally, more works in Hero Image would have deployed this approach. Some of FitzPatrick’s works veer uncomfortably close to the visual language of centrist demonology, and, as such, risk overlooking those aspects of Trump’s political brand that make him a compelling figure to love and hate. For the most part, however, Hero Image is sophisticated and refreshing given a common tendency in contemporary media to either depoliticise Trump by attempting to ignore him altogether, or to hyperpoliticise him as the cause of any and all political and economic crises. While Trump’s impact on contemporary culture and politics cannot be denied, the fantasy that something will be overcome through Trump’s elimination—a fantasy that seems to have provoked a remarkable two assassination attempts during a single campaign—forecloses too many necessary reckonings with the fallout of roughly 50 years of neoliberalism. In this sense, Hero Image generally succeeds where so many artistic responses to Trump fail insofar as FitzPatrick is able to contend with Trump the screen—onto which liberal and conservative fantasies are projected.

Nick FitzPatrick, Hero Image, Light Works, 1 November – 3 November 2024.

All artworks by and images courtesy of Nick FitzPatrick:

1. Hero Image “Big Hand” (Reuters), 2023, JPEG, 4408 x 6122 px, 18.7 MB.

2. Installation photograph of Hero Image “Flag” (Al Jazeera), 2024, JPEG, 2416 x 3469 px, 8.2 MB.

3. Installation photograph of Hero Image “Resolute” (Fox News), 2023, JPEG, 2363 x 2000 px, 10.2 MB.

4. Installation photograph of Hero Image “County Jail” (Fox News), 2023, JPEG, 2813 x 5000 px, 17.9 MB.

5. Installation photograph of Hero Image “China” (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), 2023, 16-colour GIF, 1483 x 2225 px, 0.9 MB.

6. Hero Image “Bandaged Ear” (Reuters), 2024, JPEG, 3464 x 3464 px, 2.3 MB.

7. Hero Image “Speech” (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), 2023, JPEG, 3712 x 5568 px, 14 MB

8. Installation photograph of Hero Image “Ear” (The Guardian), 2024, JPEG, 4454 x 7916 px, 28.7 MB.

9. Installation photograph of Hero Image “McDonald’s” (Al Jazeera), 2024, JPEG, 3374 x 1901 px, 6.8 MB.

10. Installation photograph of Hero Image at Light Works.

Days after an event that few cared about any longer, centrist and liberal pundits were fervent in their condemnation of the phoniness of Trump’s “shift” as a McDonald’s crew member. Guardian readers, for instance, were informed that the franchise in question had been shut down in order to facilitate the simulation of food service, with closely vetted customers playacting at surprise when encountering the Presidential hopeful at the drive through window. It was a media-event, so liberals underlined; a concocted state of affairs that was designed for media circulation and consumption only, and that would not have existed if it could not have been made viral through the channels of digital media.

However, and as Jean Baudrillard exhaustively reminded us in the 1980s and 1990s, many of the fakest aspects of contemporary consumer culture function to maintain the fiction that “out there” beyond all of the media fakery, political spin, and advertising gloss, there remains something true, real, and authentic. As Baudrillard wrote in his Simulacra and Simulation, “Disneyland exists in order to hide that it is the ‘real’ country, all of ‘real’ America that is Disneyland”. The liberal response to Trump’s McDonald’s stunt, the desperate attempt to point out that Trump’s activities are a stage-managed fraud, as opposed to the real and authentic politics apparently occurring elsewhere, is almost too perfect an illustration of Baudrillard’s point.

Interestingly, during the late 2000s and early 2010s, Trump and Baudrillard appeared to suffer a similar fate, becoming brands that existed merely for their self-reproduction. Although I never connected the two figures at the time, watching The Apprentice and reading Baudrillard in the late 2000s, I implicitly understood that both Trump and Baudrillard were viewed by many as self-parodies. The Trump and Baudrillard brands were both past it; bigger than ever, but straining for relevance, which is why, years later, it was so jarring to see the immense about-turn in their cultural impact. Indeed, riffs like the aforementioned quote from Simulacra and Simulation once seemed tired and hackneyed in a manner not dissimilar to Trump’s catchphrase “you’re fired!”—and so, after the election of Trump in 2016, it was quite a shock to find that Baudrillard’s work had gone from seemingly outlandish and metaphysical to having an almost straightforward empirical veracity, and that Trump had become one of the world’s most powerful people.

The fact that liberal critiques of Trump’s McDonald’s stunt were beside the point speaks to a longer struggle to understand Trump’s aesthetic appeal shared by centrist pundits and political operators alike. Trump’s political aesthetics have always oscillated between the banal—think of Trump’s iconic Make America Great Again hat with its oddly minimal use of the Century Schoolbook font—the grotesque—his spray tan and hair, not to mention the Trump/4chan nexus and the millions of Pepe and Groyper Trump memes—and, perhaps the most obvious, kitsch—such as Trump’s love for Rococo gold ornamentation, the paintings of Jon McNaughton, and Trump digital trading cards. For a decade now, liberals have more or less repeated Seth Meyers’ admittedly funny roast of Trump at the 2011 White House Correspondents’ dinner, and yet, the ineffectiveness of this strategy has somehow failed to provoke even a moment of self-reflection. Such attacks seem to have only reinforced Trump’s status as a normcore plutocrat, the label used by cultural theorist Jo Littler to refer to those elite insiders who have maintained an image as outsiders—as underdogs, as “one of the lads”, as inexplicably both exceedingly rich and yet relatable. Indeed, it is perhaps the case that the resilience of Trump’s aesthetic has produced a kind of monomania in the liberal unconscious, and this has inhibited Trump’s opponents in switching up their tactics. Faced with a double injury—not only the maddening fact that so many people find Trump’s banality, grotesquery, and kitschness appealing, but, even worse, they prefer him over us!—liberals appear doomed to enact the repetition compulsion of freaking out, again and again, in response to Trump’s lies, indecency, and criminality.

Given these preambulatory concerns, Nick FitzPatrick’s Hero Image (exhibited at Light Works) could not be timelier. As the artist describes, the show consists of ‘nine rephotographs’ or digitally reproduced digital images, in the attempt to seize, reconfigure, and disfigure ‘the mercurial and hyperreal media image of Donald Trump’. Displayed on a series of phones, tablets, and television screens in the tunnel entrance to Light Works’ courtyard, the opening night buzz of chatter echoed through the space to immediately evoke the background noise of incessant talking that has followed Trump—and that Trump has contributed to—throughout his political career. Reproducing images sourced from Al Jazeera, ABC, The Guardian, Reuters, and of course Fox News, these rephotographic works showcase various levels of intervention; some limited to shifts in hue, saturation, and blur, while others appear to have involved material interventions during image production to reveal skeletal and demonic forms.

The works in Hero Image are at their most successful when they engage in a strategy of immanent critique. Rather than attempting to satirise Trump from within an incompatible system of aesthetic and cultural values—from within, for example, the visual languages of contemporary painting and sculpture and the moral vocabulary of liberalism or a more diffuse form of progressivism—the best of Hero Image attempts to critique Trump on his own terms. For instance, all of the works present Trump to us by way of the very digital screens that facilitate his media status. While this approach risks disappointing the viewer, insofar as a critique of Trump does not arrive by way of a more obvious artistic intervention, Hero Image does not shy away from the unavoidable banality of the phone or tablet in the visual culture of contemporary life. Moreover, the works that showcase the viscerality of Trump’s form are more interesting than many conventional satirical Trump images in that they do not beautify as they lampoon. An odd feature of many of the last decade’s Trump impressions and parodies is their unwillingness to contend with just how bizarre Trump’s appearance and behaviour can be. Rather than delving into Trump’s depravity, popular artistic rebukes of Trump—whether Edel Rodriguez’s Time Magazine covers or Alec Baldwin’s SNL impressions—are so often too slick and smooth to really capture what is unsettling about Trump’s aesthetic interventions into the politics of the last decade. Whether through closeups of grimaces or jowls, Hero Image consistently succeeds in allowing a return of the repressed by unflinchingly exploring Trump’s capacity to produce abject and ambivalent images.

Ultimately, however, the most successful work in Hero Image is the least modified. The large glowing Hero Image “Big Hand” (Reuters) offers little in the way of condemnation or ridicule, but instead confronts the viewer with Trump as a diffuse exaggerated media figure. The critical strategy here feels reminiscent of Jeff Koons’ works on power, such as his 1988 sculpture Bear and Policeman. Inflating and blurring Trump’s saluting hand suggests both the menace of authoritarianism and the cartoonish innocence of a mascot. All plasma and electricity, Hero Image “Big Hand” (Reuters) reveals Trump as vast, soft, dumb, and empty, but in a way that is haunting and utterly transfixing. It is undoubtedly this standout work that captures the combination of power and stupidity, banality and violence, fun and terror that is characteristic of the libidinal investments afforded by Trump.

Ideally, more works in Hero Image would have deployed this approach. Some of FitzPatrick’s works veer uncomfortably close to the visual language of centrist demonology, and, as such, risk overlooking those aspects of Trump’s political brand that make him a compelling figure to love and hate. For the most part, however, Hero Image is sophisticated and refreshing given a common tendency in contemporary media to either depoliticise Trump by attempting to ignore him altogether, or to hyperpoliticise him as the cause of any and all political and economic crises. While Trump’s impact on contemporary culture and politics cannot be denied, the fantasy that something will be overcome through Trump’s elimination—a fantasy that seems to have provoked a remarkable two assassination attempts during a single campaign—forecloses too many necessary reckonings with the fallout of roughly 50 years of neoliberalism. In this sense, Hero Image generally succeeds where so many artistic responses to Trump fail insofar as FitzPatrick is able to contend with Trump the screen—onto which liberal and conservative fantasies are projected.

Nick FitzPatrick, Hero Image, Light Works, 1 November – 3 November 2024.

All artworks by and images courtesy of Nick FitzPatrick:

1. Hero Image “Big Hand” (Reuters), 2023, JPEG, 4408 x 6122 px, 18.7 MB.

2. Installation photograph of Hero Image “Flag” (Al Jazeera), 2024, JPEG, 2416 x 3469 px, 8.2 MB.

3. Installation photograph of Hero Image “Resolute” (Fox News), 2023, JPEG, 2363 x 2000 px, 10.2 MB.

4. Installation photograph of Hero Image “County Jail” (Fox News), 2023, JPEG, 2813 x 5000 px, 17.9 MB.

5. Installation photograph of Hero Image “China” (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), 2023, 16-colour GIF, 1483 x 2225 px, 0.9 MB.

6. Hero Image “Bandaged Ear” (Reuters), 2024, JPEG, 3464 x 3464 px, 2.3 MB.

7. Hero Image “Speech” (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), 2023, JPEG, 3712 x 5568 px, 14 MB

8. Installation photograph of Hero Image “Ear” (The Guardian), 2024, JPEG, 4454 x 7916 px, 28.7 MB.

9. Installation photograph of Hero Image “McDonald’s” (Al Jazeera), 2024, JPEG, 3374 x 1901 px, 6.8 MB.

10. Installation photograph of Hero Image at Light Works.