In the wake of the 2023 ‘Voice’ referendum, Rohin Kickett and Matthew McVeigh’s Custodians, a new public sculpture in the Murdoch Hospital precinct, symbolises the ‘reconciliation from below’ that is taking the place of top down, government driven change to policies around Aboriginal Australia. Sitting at the entrance to the hospital’s office blocks, the sculpture is made of two giant, cupped hands that hold a young eucalypt in a small circular garden. They are wrapped gently around the thin and sickly looking tree, as one might hold an origami crane. It’s an effective piece of oversized public art, its skin coloured a yellow-gold, the hand’s dimples and lines giving the hands a vibrant, living look. As a welcome to the hospital’s sterile spaces, the hands offer a metaphor for care, but as the hands of Noongar elder Aunty Francine Kickett they also symbolise ‘caring for Country’—though as a private hospital, there may not be many Aboriginal people coming through its doors.

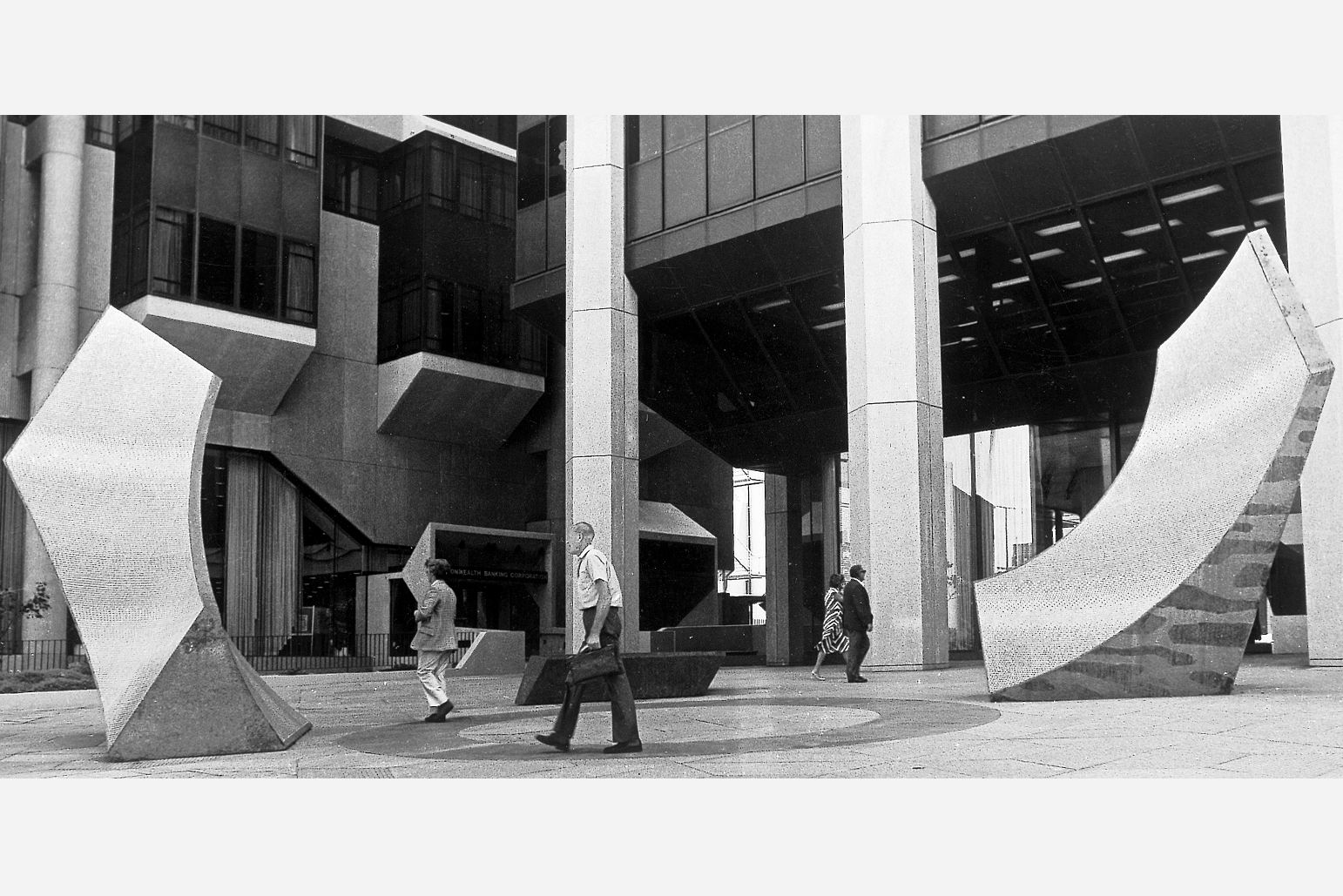

In its collaboration and vision, Custodians is one of the most ambitious pieces of public art Perth has seen for some time. We don’t get works like this very often. Unveiled in 1999, there is Tony Jones’s C.Y. O’Connor, Horse and Rider of the famed engineer drowning himself at the beach, and Marcus Canning’s Rainbow, better known as the “Containbow” of 2016. The first channelled West Australian anxieties around high rates of suicide and depression on Australia’s remote mines, while the second’s Pride colours coincided with the same-sex marriage survey. These sculptures age well because they configure the hopes and despairs of their zeitgeist, representing moments in time that are embedded in the state’s psyche. The precedent for Custodians is Howard Taylor’s The Black Stump (1975) that also welcomed pedestrians, not to the Murdoch Hospital but to the AMP building on St Georges Terrace with open, circular, forms. Black Stump too sat under towers that loomed above it, setting its organic forms against the geometries of the city. While Taylor’s sculpture was something of a protest against an agriculture boom that had cleared much of the south-west for wheat fields, Kickett and McVeigh’s Custodians plays out an ongoing plea for the recognition of Aboriginal people after the failure of the Voice referendum.

Francine Kickett’s hands represent a country held by Aboriginal hands, and in their gentle, open gesture symbolise both care and the utopian ideals that the referendum failed to realise: the sense of intimacy, sharing and listening necessary for this process of fundamental political change. These sensitive aspects of the sculpture are, however, in a dialogical relation with its shining, golden colour and its gargantuan form. These are forms of totalitarian sculpture and speak not to the anxieties that are likely to be behind the referendum’s failure, but to the way in which the Aboriginal ownership of the country is a claim of moral and historical authority that stands both before and above the claims of the settler population.

To make sense of this tension in Custodians, we can turn to radical Chinese sculptors who in the face of an oppressive regime also make this kind of ‘reverse monument’. Their oversized portraits and sculptures of Mao parody the state totalitarianism not only of Mao and Xi, his successor, but the problem of state capitalism itself. Mao stands for the concentration of authority and power, and in parodying his overblown representation in posters, public sculptures and in daily life, Chinese artists reverse his authority. The bright gold of Custodians functions as red does in these Chinese reverse monuments; the bright, audacious reflection of the sun under Murdoch’s hospital towers alluding to the gift of the country, the gift of wealth, offered by the promise of reconciliation. This loving gesture catches the other, the settler and migrant, in their own failure to accept the gift. The gesture remains just that: a gesture unrequited and beautiful, monumental and golden.

If Custodians creates an image of the movement to place Aboriginality at the centre of the Australian experience, it also speaks to the contradictions that come with doing so, its reverse totalitarianism giving shape to the alienation that comes with a national discourse around the fate of its First Peoples. To insist, as the referendum did, that Aboriginal people are holders of a privileged place within the nation is not only a form of recognition but a symbolic burden. The referendum aspired to tether the nation’s identity to Indigenous people, to tie their fate to that of the nation. Kickett and McVeigh’s sculpture is a compelling picture of this zeitgeist, illustrating the totalitarianism implicit in this vision of the Australian nation-state. To imagine that Australia could be one, and that Indigenous people would offer a key to this oneness, burdens the future by erasing the past, creating an illusion of reconciliation amidst an ongoing difference and series of differences between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous, as well as within the Indigenous and non-Indigenous. The opening of Kickett’s hands recalls the generosity that lay underneath the referendum, the 2017 Uluru Statement that lay a path toward reconciliation. This would become an unrequited generosity after the referendum, as Kickett’s hands open into a gesture of hope, a monument to a historical opportunity that never came to pass.

Images:

1. Rohin Kickett and Matthew McVeigh, Custodians, Murdoch Square, 2024.

2. Howard Taylor’s The Black Stump, 1975.

3. Rohin Kickett and Matthew McVeigh, Custodians, Murdoch Square, 2024.

In its collaboration and vision, Custodians is one of the most ambitious pieces of public art Perth has seen for some time. We don’t get works like this very often. Unveiled in 1999, there is Tony Jones’s C.Y. O’Connor, Horse and Rider of the famed engineer drowning himself at the beach, and Marcus Canning’s Rainbow, better known as the “Containbow” of 2016. The first channelled West Australian anxieties around high rates of suicide and depression on Australia’s remote mines, while the second’s Pride colours coincided with the same-sex marriage survey. These sculptures age well because they configure the hopes and despairs of their zeitgeist, representing moments in time that are embedded in the state’s psyche. The precedent for Custodians is Howard Taylor’s The Black Stump (1975) that also welcomed pedestrians, not to the Murdoch Hospital but to the AMP building on St Georges Terrace with open, circular, forms. Black Stump too sat under towers that loomed above it, setting its organic forms against the geometries of the city. While Taylor’s sculpture was something of a protest against an agriculture boom that had cleared much of the south-west for wheat fields, Kickett and McVeigh’s Custodians plays out an ongoing plea for the recognition of Aboriginal people after the failure of the Voice referendum.

Francine Kickett’s hands represent a country held by Aboriginal hands, and in their gentle, open gesture symbolise both care and the utopian ideals that the referendum failed to realise: the sense of intimacy, sharing and listening necessary for this process of fundamental political change. These sensitive aspects of the sculpture are, however, in a dialogical relation with its shining, golden colour and its gargantuan form. These are forms of totalitarian sculpture and speak not to the anxieties that are likely to be behind the referendum’s failure, but to the way in which the Aboriginal ownership of the country is a claim of moral and historical authority that stands both before and above the claims of the settler population.

To make sense of this tension in Custodians, we can turn to radical Chinese sculptors who in the face of an oppressive regime also make this kind of ‘reverse monument’. Their oversized portraits and sculptures of Mao parody the state totalitarianism not only of Mao and Xi, his successor, but the problem of state capitalism itself. Mao stands for the concentration of authority and power, and in parodying his overblown representation in posters, public sculptures and in daily life, Chinese artists reverse his authority. The bright gold of Custodians functions as red does in these Chinese reverse monuments; the bright, audacious reflection of the sun under Murdoch’s hospital towers alluding to the gift of the country, the gift of wealth, offered by the promise of reconciliation. This loving gesture catches the other, the settler and migrant, in their own failure to accept the gift. The gesture remains just that: a gesture unrequited and beautiful, monumental and golden.

If Custodians creates an image of the movement to place Aboriginality at the centre of the Australian experience, it also speaks to the contradictions that come with doing so, its reverse totalitarianism giving shape to the alienation that comes with a national discourse around the fate of its First Peoples. To insist, as the referendum did, that Aboriginal people are holders of a privileged place within the nation is not only a form of recognition but a symbolic burden. The referendum aspired to tether the nation’s identity to Indigenous people, to tie their fate to that of the nation. Kickett and McVeigh’s sculpture is a compelling picture of this zeitgeist, illustrating the totalitarianism implicit in this vision of the Australian nation-state. To imagine that Australia could be one, and that Indigenous people would offer a key to this oneness, burdens the future by erasing the past, creating an illusion of reconciliation amidst an ongoing difference and series of differences between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous, as well as within the Indigenous and non-Indigenous. The opening of Kickett’s hands recalls the generosity that lay underneath the referendum, the 2017 Uluru Statement that lay a path toward reconciliation. This would become an unrequited generosity after the referendum, as Kickett’s hands open into a gesture of hope, a monument to a historical opportunity that never came to pass.

Images:

1. Rohin Kickett and Matthew McVeigh, Custodians, Murdoch Square, 2024.

2. Howard Taylor’s The Black Stump, 1975.

3. Rohin Kickett and Matthew McVeigh, Custodians, Murdoch Square, 2024.