One of the reasons that Francis Bacon’s painting Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953) is so unforgettable, with its Pope appearing to scream through a curtain of paint, is the way that it rewrites the history of European portraiture of kings, queens, popes and merchants. They are typically seated amidst finery, underlings, and sometimes dragons, all symbolising their power and influence. It is no coincidence that Bacon’s version of one of these classical portraits reworks a Diego Velázquez, the most modern of Early Modern artists in Europe, and yet it is only possible to see Velázquez’s modernism after seeing Bacon’s Study. The modernism of Portrait of Innocent X (c1650) lies in Velázquez’s use of paint. Modulating the difference between the eye being close and distant, a stroke of white paint turns into the hem of the Pope’s dress in a magical, illusionistic transformation that anticipates the kinds of conceptual parlour tricks of his more famous Las Meninas (1656) a few years later.

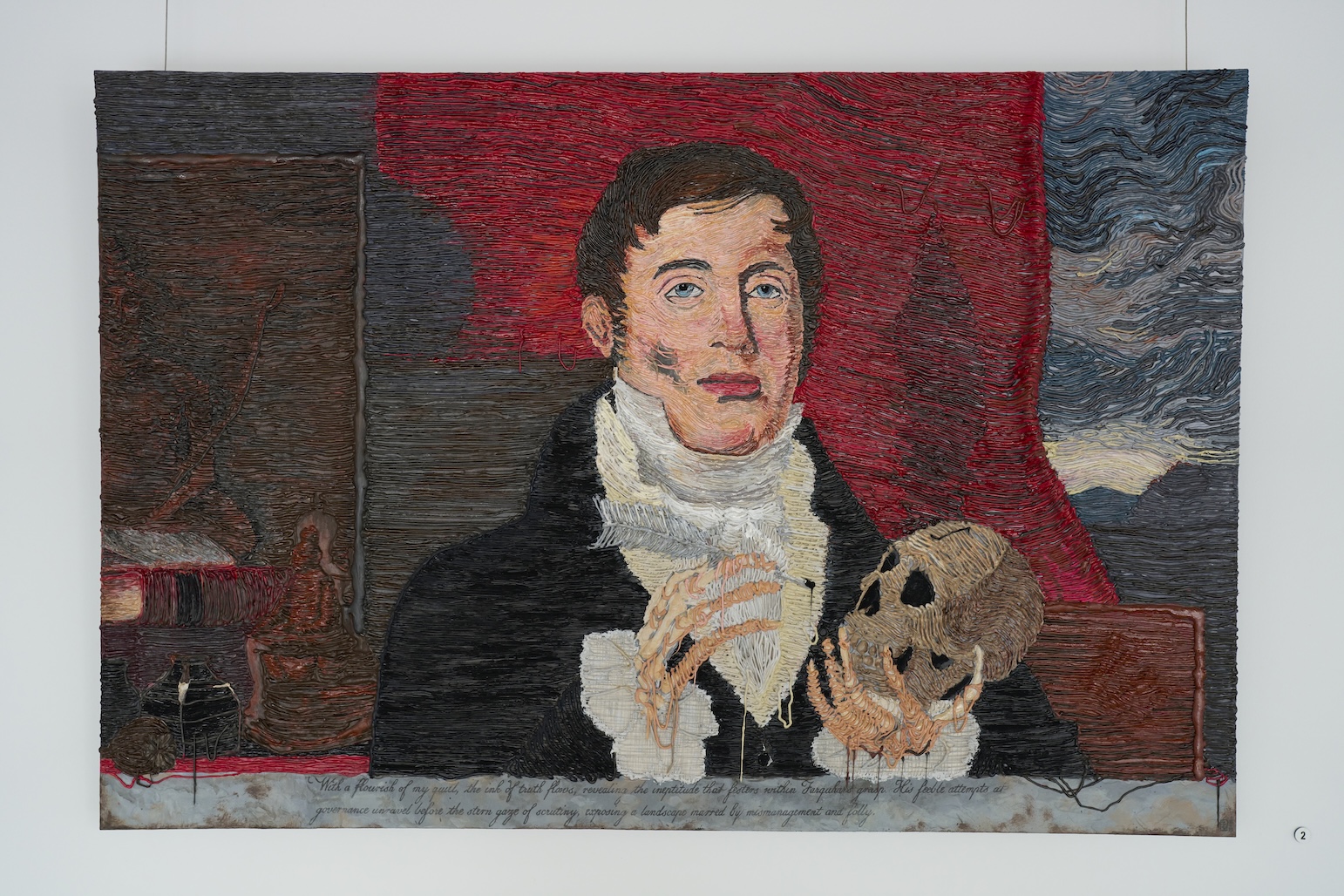

The tricks of turning a surface into a resolved image, technique into illusion, are part of the fun of Desmond Mah’s show at Mossenson Galleries. He layers thin, spaghetti-like tubes of colour atop each other to create a kind of relief painting, in a unique technique that he has perfected in this exhibition. His subjects are postcolonial, and include British diplomats and soldiers, Captain Cook and Queen Elizabeth II, as well as Stamford Raffles, the founder of Singapore. Through Mah’s tangle of paint it is impossible for the mind not to attempt to recover the portraits that served as his models, the images that have made Cook and Elizabeth such familiar figures, and yet whose appearances are known only through historical picture making. As we see through Bacon to Velázquez, and through Velázquez to centuries of the Church’s regime of arcane rituals and gauche symbology, in Mah’s exhibition we see through colonial iconicity to the troubled history of the British Empire. Mah’s tangle of paint becomes a metaphor for the complexity of the historical figure.

If the European and colonial represents one art history at play within Mah’s work, his childhood home of Singapore and its disjuncture of Asia and Englishness is another. The great, hypermodern city has what Joan Kee describes as a ‘hollowness’ that is reflected by its artists. Here Mah is preceded by other Singapore artists exhibiting in Perth, such as Lee Wen’s Yellow Man performance that means different things wherever and whenever he performs it. Lee appeared in Perth’s old railway workshops in the suburb of Midland in 2005. Painting himself yellow in front of the audience, he began to appear as a simulacrum of the cavernous building around him, the hollowness of his home hyper-city reflected in the conversion of an industrial hub into a post-industrial art venue, and the sandy, meaningless, and money grubbing city of Perth around him.

Mah’s tangled paint reliefs rework this theme of hollowness, the absences that Singapore and Perth do not have in common but commonly lack, into a colonial condition. Their mechanisms of colour and form lie like the insides of a machine and recall the tangled mess of British history, that is in both Australia and Singapore not so much a shared history but a shared absence of this history, as the British Empire belonged to someone who was not Australian or Singaporean. As artists in Singapore desperately attempt to make their voices heard amidst a conservative, censorial police state, trying to forge authenticity in the face of an artificial city, so Australian artists struggle with a history that is not their own, seeking out Indigenous collaborators or foregrounding their Indigenous heritage in attempts to overcome an unbelonging that lies as a lack within the nation’s sense of itself.

If the titles of Mah’s paintings tend toward the didactic, in I Secure My Place Whilst Disregarding Others (Capt. J. Cook) (2024), or in a series of ‘Empire Builder’ works, it is in the spirit of this postcolonial zeitgeist, this insecurity that haunts Australian and Singaporean artists. They not only sense a disjuncture with the nation around them, but in turn the lack of belonging that both places have to Asia itself. The resilience of colonial mythology in both countries, the way in which their histories both celebrate and disavow colonialism, creates an exceptionalism amidst postcolonial nationalisms elsewhere in Asia. The anachronisms in Mah’s show, including Cook, Elizabeth and Raffles, appear at a historical moment at which the postcolonial begins to appear merely postmodern, as colonial imagery and histories confront their own exhaustion in spiralling debates over history. Cook’s reproduction and revision is symptomatic of this exhaustion. We are more than three decades since Gordon Bennett’s Possession Island series (1991), and a few months since the last Australia Day, with its graffitiing and dismantling of Cook statues in the Eastern States. We live amidst not one but many Captain Cooks, as Gurindji, Mulgoa and other Aboriginal people say, with countless Captain Cooks running amok across Australia during the invasion, and more recently a swarm of Cooks in the postcolonial kitchen.

The problem with art that addresses the legacy of colonialism is that the institutions born of colonialism tend to embrace the anti-colonial because they recognise themselves within it. The anti-colonial, or postcolonial is a reverse mirror by which institutions are able to preen their collections and curatorial pretentions. The postcolonial artist is a vegetarian cooking fake tofu for the carnivorous, collecting institution.. Amidst this complexity the legacy of the colonial image is to tend less toward history and more toward the post-historical, as debates around national symbolism testify to a raging despair at the postcolonial condition. Mah’s relief paintings embody this hollowness that is not empty, this historical feeling and spaghetti-like complexity. What makes Mah’s I Secure My Place Whilst Disregarding Others (Capt. J. Cook) successful is that it lies precisely within this animating contradiction, while other, less known figures such as Dear Right Honourable Lord Hastings (2024) and a sculpture of tangled paint, Labourer No. 38 (2024), populate the history and make it more compelling as an exhibition, filling out the historical scene.

There is a difference between a show of portraits and pictures. When Perth born celebrity and paedophile Rolf Harris was commissioned to paint the Queen, for example, he painted Elizabeth instead, a smiling grandmother rather than a monarch, offending the art establishment while being embraced by the English public. The tubular lines of Mah’s Regalis Gemmiferus(2024) are a picture rather than a portrait of the Queen, their tubular accretion a metaphor for the symbolic survival of the British Empire well beyond its times. Other paintings work less well in this metaphoric space. A series of ‘Empire Builders’ are pictured with KKK-style hoods over their heads, rather than pith helmets. It is as if the pith helmets were not strong enough images for Mah, despite them being powerful images of colonial power from Africa to Asia. In 2008 postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha walked out of a keynote address by then British Museum boss Neil McGregor in Melbourne, for example, after McGregor made light of the pith helmets worn by imperial soldiers in a picture from the African Gold Coast. The use of the KKK hood loses the more precise focus upon British colonialism, stretching the colonial metaphor to a North American iconography (but admittedly one that has also appeared in rural Australia). These hoods also obscure the power of the face to create a relatable image in these works, and we lose the sense that these colonials were also subjects of Empire, human beings acting out nineteenth century ideologies. There is, however, no doubting the quality of Mah’s spidery painting technique and the way it lends itself conceptually to the colonial juggernaut, while also speaking to a longer history of painting, and to a metaphor of history as a tangled web within which we remain enmeshed.

Desmond Mah, Twisted Bodies Tell Their Stories, Mossenson Galleries, 16 October – 9 November 2024.

Images: Exhibition photos of Desmond Mah’s Twisted Bodies Tell Their Stories at Mossenson Galleries. Photography by Liang Xu.

The tricks of turning a surface into a resolved image, technique into illusion, are part of the fun of Desmond Mah’s show at Mossenson Galleries. He layers thin, spaghetti-like tubes of colour atop each other to create a kind of relief painting, in a unique technique that he has perfected in this exhibition. His subjects are postcolonial, and include British diplomats and soldiers, Captain Cook and Queen Elizabeth II, as well as Stamford Raffles, the founder of Singapore. Through Mah’s tangle of paint it is impossible for the mind not to attempt to recover the portraits that served as his models, the images that have made Cook and Elizabeth such familiar figures, and yet whose appearances are known only through historical picture making. As we see through Bacon to Velázquez, and through Velázquez to centuries of the Church’s regime of arcane rituals and gauche symbology, in Mah’s exhibition we see through colonial iconicity to the troubled history of the British Empire. Mah’s tangle of paint becomes a metaphor for the complexity of the historical figure.

If the European and colonial represents one art history at play within Mah’s work, his childhood home of Singapore and its disjuncture of Asia and Englishness is another. The great, hypermodern city has what Joan Kee describes as a ‘hollowness’ that is reflected by its artists. Here Mah is preceded by other Singapore artists exhibiting in Perth, such as Lee Wen’s Yellow Man performance that means different things wherever and whenever he performs it. Lee appeared in Perth’s old railway workshops in the suburb of Midland in 2005. Painting himself yellow in front of the audience, he began to appear as a simulacrum of the cavernous building around him, the hollowness of his home hyper-city reflected in the conversion of an industrial hub into a post-industrial art venue, and the sandy, meaningless, and money grubbing city of Perth around him.

Mah’s tangled paint reliefs rework this theme of hollowness, the absences that Singapore and Perth do not have in common but commonly lack, into a colonial condition. Their mechanisms of colour and form lie like the insides of a machine and recall the tangled mess of British history, that is in both Australia and Singapore not so much a shared history but a shared absence of this history, as the British Empire belonged to someone who was not Australian or Singaporean. As artists in Singapore desperately attempt to make their voices heard amidst a conservative, censorial police state, trying to forge authenticity in the face of an artificial city, so Australian artists struggle with a history that is not their own, seeking out Indigenous collaborators or foregrounding their Indigenous heritage in attempts to overcome an unbelonging that lies as a lack within the nation’s sense of itself.

If the titles of Mah’s paintings tend toward the didactic, in I Secure My Place Whilst Disregarding Others (Capt. J. Cook) (2024), or in a series of ‘Empire Builder’ works, it is in the spirit of this postcolonial zeitgeist, this insecurity that haunts Australian and Singaporean artists. They not only sense a disjuncture with the nation around them, but in turn the lack of belonging that both places have to Asia itself. The resilience of colonial mythology in both countries, the way in which their histories both celebrate and disavow colonialism, creates an exceptionalism amidst postcolonial nationalisms elsewhere in Asia. The anachronisms in Mah’s show, including Cook, Elizabeth and Raffles, appear at a historical moment at which the postcolonial begins to appear merely postmodern, as colonial imagery and histories confront their own exhaustion in spiralling debates over history. Cook’s reproduction and revision is symptomatic of this exhaustion. We are more than three decades since Gordon Bennett’s Possession Island series (1991), and a few months since the last Australia Day, with its graffitiing and dismantling of Cook statues in the Eastern States. We live amidst not one but many Captain Cooks, as Gurindji, Mulgoa and other Aboriginal people say, with countless Captain Cooks running amok across Australia during the invasion, and more recently a swarm of Cooks in the postcolonial kitchen.

The problem with art that addresses the legacy of colonialism is that the institutions born of colonialism tend to embrace the anti-colonial because they recognise themselves within it. The anti-colonial, or postcolonial is a reverse mirror by which institutions are able to preen their collections and curatorial pretentions. The postcolonial artist is a vegetarian cooking fake tofu for the carnivorous, collecting institution.. Amidst this complexity the legacy of the colonial image is to tend less toward history and more toward the post-historical, as debates around national symbolism testify to a raging despair at the postcolonial condition. Mah’s relief paintings embody this hollowness that is not empty, this historical feeling and spaghetti-like complexity. What makes Mah’s I Secure My Place Whilst Disregarding Others (Capt. J. Cook) successful is that it lies precisely within this animating contradiction, while other, less known figures such as Dear Right Honourable Lord Hastings (2024) and a sculpture of tangled paint, Labourer No. 38 (2024), populate the history and make it more compelling as an exhibition, filling out the historical scene.

There is a difference between a show of portraits and pictures. When Perth born celebrity and paedophile Rolf Harris was commissioned to paint the Queen, for example, he painted Elizabeth instead, a smiling grandmother rather than a monarch, offending the art establishment while being embraced by the English public. The tubular lines of Mah’s Regalis Gemmiferus(2024) are a picture rather than a portrait of the Queen, their tubular accretion a metaphor for the symbolic survival of the British Empire well beyond its times. Other paintings work less well in this metaphoric space. A series of ‘Empire Builders’ are pictured with KKK-style hoods over their heads, rather than pith helmets. It is as if the pith helmets were not strong enough images for Mah, despite them being powerful images of colonial power from Africa to Asia. In 2008 postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha walked out of a keynote address by then British Museum boss Neil McGregor in Melbourne, for example, after McGregor made light of the pith helmets worn by imperial soldiers in a picture from the African Gold Coast. The use of the KKK hood loses the more precise focus upon British colonialism, stretching the colonial metaphor to a North American iconography (but admittedly one that has also appeared in rural Australia). These hoods also obscure the power of the face to create a relatable image in these works, and we lose the sense that these colonials were also subjects of Empire, human beings acting out nineteenth century ideologies. There is, however, no doubting the quality of Mah’s spidery painting technique and the way it lends itself conceptually to the colonial juggernaut, while also speaking to a longer history of painting, and to a metaphor of history as a tangled web within which we remain enmeshed.

Desmond Mah, Twisted Bodies Tell Their Stories, Mossenson Galleries, 16 October – 9 November 2024.

Images: Exhibition photos of Desmond Mah’s Twisted Bodies Tell Their Stories at Mossenson Galleries. Photography by Liang Xu.