At the edge of Northbridge sits a

pocket of the city that feels almost self-contained. It is an eclectic corner

crowded with late-night eateries, gaming rooms, and bubble tea counters. Tucked

among these fluorescent shopfronts and the steady hum of foot traffic is

_____g.s (otherwise

known as Underscore Gallery Space), an unlikely yet fitting home for some of

Perth’s more experimental art practices. It is a venue where the grit of the

local art scene brushes up against the everyday rhythms of the neighbourhood,

never fully separating itself from the street outside. It is this uneasy

proximity between an art space and street life that makes _____g.s particularly

receptive to a performance artist like Lucas “Granpa” Abela, formerly known as

Justice Yeldham. Abela’s work pushes sound beyond conventional musical

structures, finding its footing in environments that resist polish and

predictability. Even before Abela produced a single sound, the setting itself

suggested that this would not be a performance for passive listening, but one

requiring a more deliberate and attentive form of engagement.

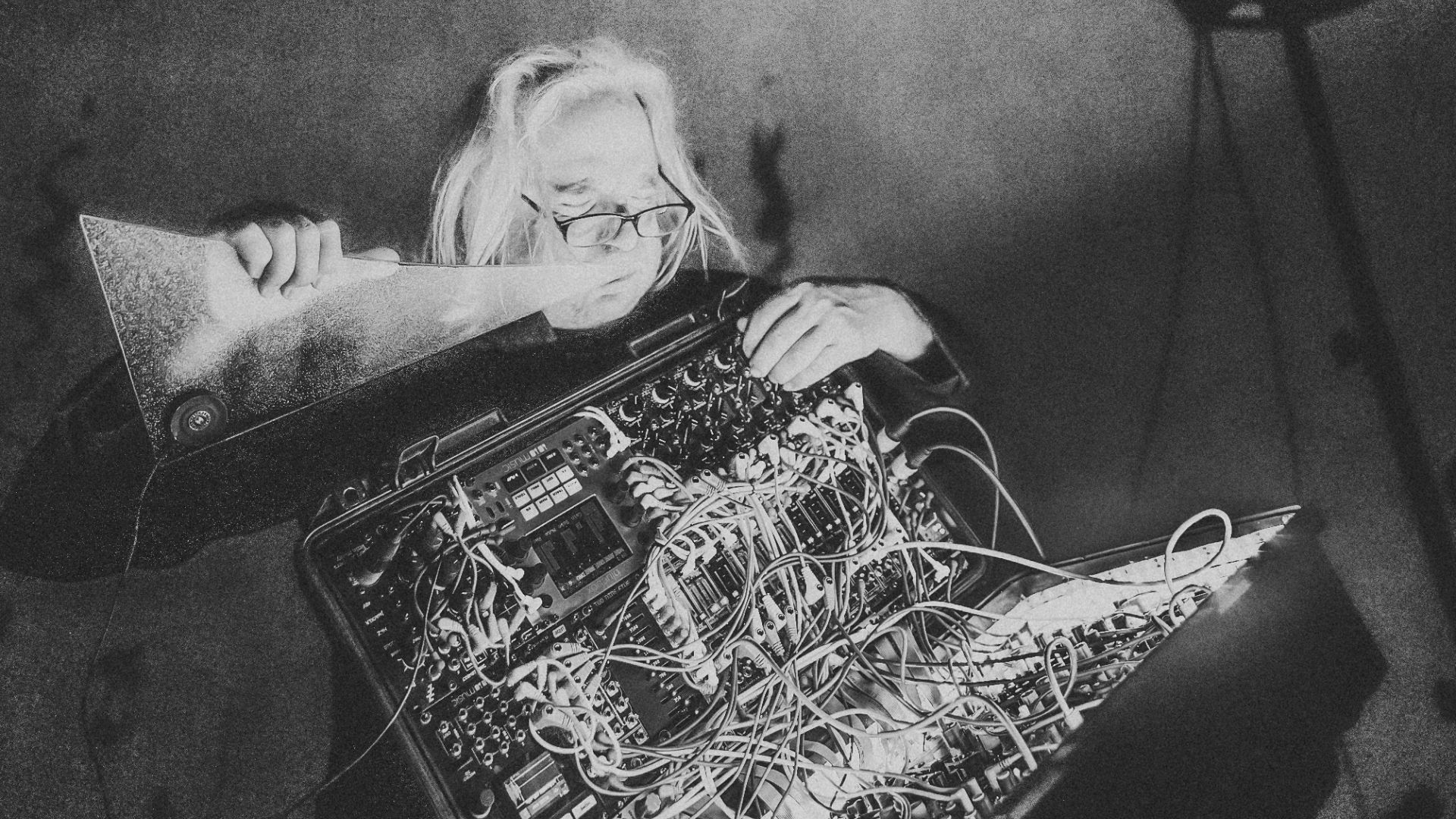

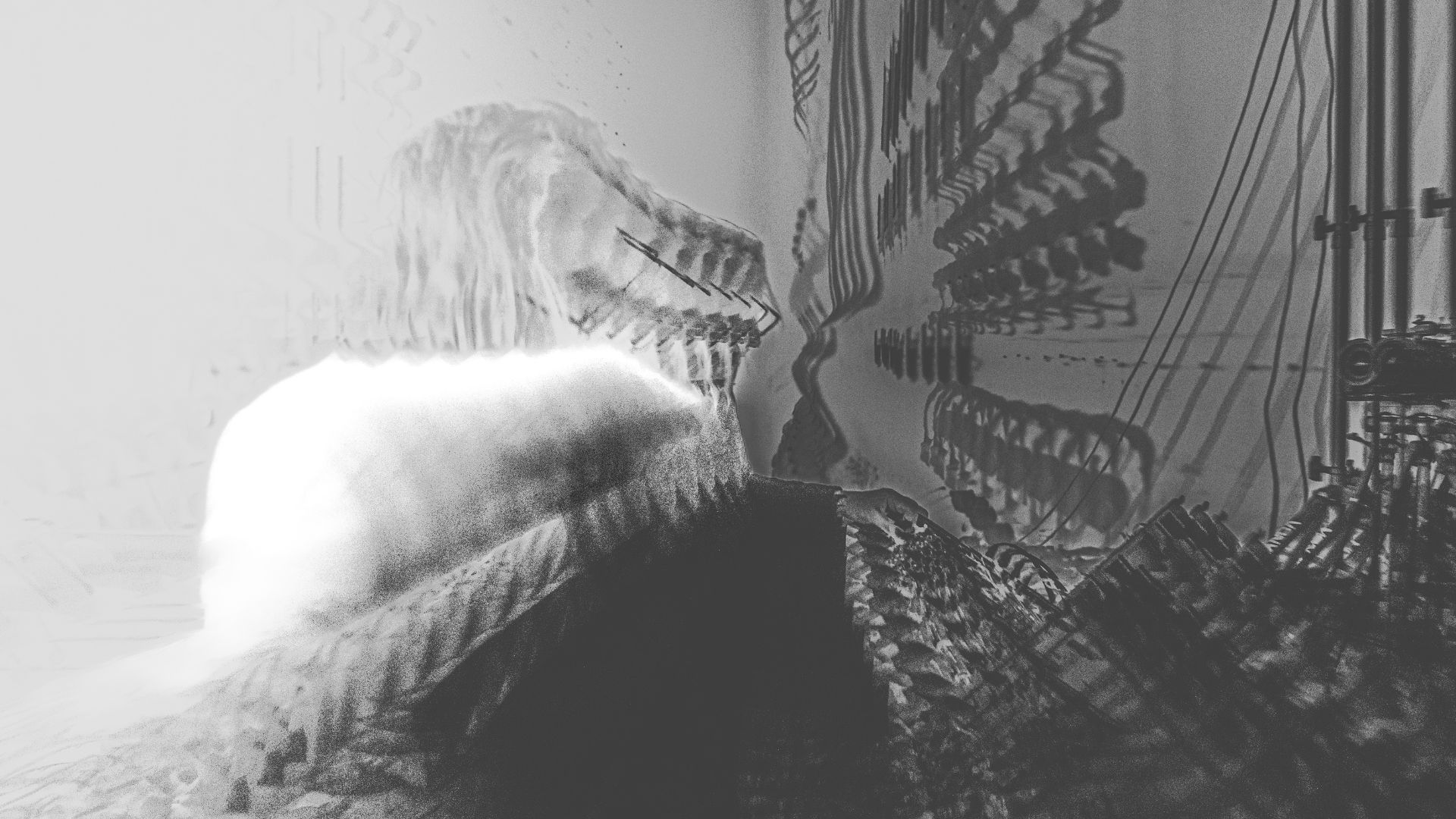

That expectation is inextricably linked to Abela’s long-standing practice. As an Australian experimental musician and performance artist, he has spent more than two decades operating at the outer limits of noise music, where sound functions less as composition and more as a physical and psychological force. His performances often involve large shards of glass treated as instruments, generating harsh, unstable sounds that blur the boundaries between music, bodily endurance, and sensory confrontation. Touring extensively both in Australia and internationally, Abela has developed a reputation for intensity and abrasiveness. Yet beyond the immediate shock value of his performances, Abela’s practice is driven by a sustained interest in how sound can disrupt habitual listening and unsettle an audience’s relationship to comfort and control. During his performance at _____g.s, these concerns became materially and perceptually present. The work unfolded less like a sequence of moments and more like an atmosphere that settled over the room. Sound arrived abruptly, jagged, and unannounced, then lingered in uneasy suspension. There was no sense of build or release, only a steady insistence that refused to guide the listener toward any point of orientation. Time stretched and compressed in strange ways, with each burst of sound blurring into the next, making it difficult to anticipate what might follow or when it might end.

While Abela’s practice is often framed through its extremity, my response oscillated between fascination and resistance. I liked the performance not despite its discomfort, but because of it; it scratched an itch in my brain while simultaneously making me want to claw at my own skin. That conclusion, however, took time to arrive. My initial response was shaped by the absence of anything familiar to hold onto. With no rhythm to follow or pattern to settle into, I struggled to find my footing as a listener. Instead of being carried by the sound, I became acutely aware of my own mind at work, searching for structure and anticipating change but repeatedly encountering refusal. Over time, that resistance became the source of the work’s appeal. The performance demanded a relinquishing of control, keeping both body and attention in a state of heightened alertness. What began as discomfort gradually shifted into a form of cognitive stimulation with an insistence on staying present. At moments, the sound felt less like something entering through the ears than something pressing against the body, vibrating through the room and making sustained attention feel physical, almost muscular. In this way, enjoyment emerged not through ease or familiarity, but through the ongoing friction between a desire for order and its persistent denial.

Rather than losing myself in the sound, I became increasingly aware of my own efforts to impose structure on it. What held my attention was not unease alone, but a growing curiosity about the psychology of noise music, specifically what draws some listeners toward its raw intensity while leaving others feeling uncertain and unsettled. Abela’s work operates where sound slips into sensation, foregrounding the mental and bodily dynamics that shape how audiences encounter noise. Noise theorist Paul Hegarty describes noise music as existing in a space of productive discomfort. This space hovers between attraction and irritation, pleasure and repulsion.[1] That ambivalence felt palpable throughout Abela’s performance. Deprived of any stable point of entry, the listener was held in a constant state of attentiveness. The work, instead of offering release or resolution, demanded presence, refusing to settle into something legible or comforting. This helps explain why responses to noise music are often so polarised: for some, the intensity sharpens focus and heightens sensory engagement; for others, it triggers resistance as the mind searches for patterns that never materialise.

![]()

Across the room, however, the audience appeared strikingly receptive. Heads bobbed in loose, unselfconscious rhythm, bodies subtly moving perceptibly in response to the jagged sound. The atmosphere felt attentive as opposed to tense, as if many listeners had already accepted the terms of the encounter and were moving with the noise instead of against it. This physical responsiveness suggested a familiarity with discomfort, a willingness to allow sound to register through the body rather than be neatly interpreted. Throughout the performance, the mechanisms listeners typically rely on to orient themselves were systematically denied. Without rhythm or progression to anchor attention, the work offered no basis for anticipation or coherence. This denial of recognisable musical cues ultimately shaped its appeal, requiring endurance instead of immersion and positioning discomfort as an active mode of engagement. In line with Hegarty’s framing, enjoyment emerged through the ongoing oscillation between attraction and irritation, keeping the listener alert, unsettled, and engaged.

In this context, the performance worked not by overcoming discomfort, but by sustaining it. Abela’s joyful denial of resolution or ease was deliberate yet never alienating, positioning endurance as a central part of the listening experience. What lingered was not a melody, moment, or release, but an awareness of how attention was being held, tested, and repeatedly redirected. The work asked for commitment rather than surrender, rewarding persistence with heightened sensitivity rather than comfort.

_____g.s proved to be a fitting site for this encounter. Its proximity to the street, modest scale, and resistance to polish mirrored the conditions of the performance itself. The space did not insulate the work from the world outside, nor did it soften its edges. Instead, it reinforced the sense that this was an experience unfolding within everyday life, not apart from it, one that demanded presence amid distraction. In an era where listening is often fragmented and mediated, Abela’s performance foregrounded attention as something physical, effortful, and, at times, uncomfortable. It challenged the expectation that engagement should be seamless or immediately gratifying, suggesting instead that sustained focus may require friction. In doing so, the work reframed discomfort not as a barrier to enjoyment, but as a condition through which a different kind of listening might emerge.

Lucas “Granpa” Abela’s performance took place at _____g.s on 22 November 2025.

Footnote:

1. Paul Hegarty, Noise/Music: A History (New York: Continuum, 2007), Introduction, pp. 1–7.

Image credits: Lucas Abela performing at _____g.s, photographed by Joe Rae @convectionpattern.

That expectation is inextricably linked to Abela’s long-standing practice. As an Australian experimental musician and performance artist, he has spent more than two decades operating at the outer limits of noise music, where sound functions less as composition and more as a physical and psychological force. His performances often involve large shards of glass treated as instruments, generating harsh, unstable sounds that blur the boundaries between music, bodily endurance, and sensory confrontation. Touring extensively both in Australia and internationally, Abela has developed a reputation for intensity and abrasiveness. Yet beyond the immediate shock value of his performances, Abela’s practice is driven by a sustained interest in how sound can disrupt habitual listening and unsettle an audience’s relationship to comfort and control. During his performance at _____g.s, these concerns became materially and perceptually present. The work unfolded less like a sequence of moments and more like an atmosphere that settled over the room. Sound arrived abruptly, jagged, and unannounced, then lingered in uneasy suspension. There was no sense of build or release, only a steady insistence that refused to guide the listener toward any point of orientation. Time stretched and compressed in strange ways, with each burst of sound blurring into the next, making it difficult to anticipate what might follow or when it might end.

While Abela’s practice is often framed through its extremity, my response oscillated between fascination and resistance. I liked the performance not despite its discomfort, but because of it; it scratched an itch in my brain while simultaneously making me want to claw at my own skin. That conclusion, however, took time to arrive. My initial response was shaped by the absence of anything familiar to hold onto. With no rhythm to follow or pattern to settle into, I struggled to find my footing as a listener. Instead of being carried by the sound, I became acutely aware of my own mind at work, searching for structure and anticipating change but repeatedly encountering refusal. Over time, that resistance became the source of the work’s appeal. The performance demanded a relinquishing of control, keeping both body and attention in a state of heightened alertness. What began as discomfort gradually shifted into a form of cognitive stimulation with an insistence on staying present. At moments, the sound felt less like something entering through the ears than something pressing against the body, vibrating through the room and making sustained attention feel physical, almost muscular. In this way, enjoyment emerged not through ease or familiarity, but through the ongoing friction between a desire for order and its persistent denial.

Rather than losing myself in the sound, I became increasingly aware of my own efforts to impose structure on it. What held my attention was not unease alone, but a growing curiosity about the psychology of noise music, specifically what draws some listeners toward its raw intensity while leaving others feeling uncertain and unsettled. Abela’s work operates where sound slips into sensation, foregrounding the mental and bodily dynamics that shape how audiences encounter noise. Noise theorist Paul Hegarty describes noise music as existing in a space of productive discomfort. This space hovers between attraction and irritation, pleasure and repulsion.[1] That ambivalence felt palpable throughout Abela’s performance. Deprived of any stable point of entry, the listener was held in a constant state of attentiveness. The work, instead of offering release or resolution, demanded presence, refusing to settle into something legible or comforting. This helps explain why responses to noise music are often so polarised: for some, the intensity sharpens focus and heightens sensory engagement; for others, it triggers resistance as the mind searches for patterns that never materialise.

Across the room, however, the audience appeared strikingly receptive. Heads bobbed in loose, unselfconscious rhythm, bodies subtly moving perceptibly in response to the jagged sound. The atmosphere felt attentive as opposed to tense, as if many listeners had already accepted the terms of the encounter and were moving with the noise instead of against it. This physical responsiveness suggested a familiarity with discomfort, a willingness to allow sound to register through the body rather than be neatly interpreted. Throughout the performance, the mechanisms listeners typically rely on to orient themselves were systematically denied. Without rhythm or progression to anchor attention, the work offered no basis for anticipation or coherence. This denial of recognisable musical cues ultimately shaped its appeal, requiring endurance instead of immersion and positioning discomfort as an active mode of engagement. In line with Hegarty’s framing, enjoyment emerged through the ongoing oscillation between attraction and irritation, keeping the listener alert, unsettled, and engaged.

In this context, the performance worked not by overcoming discomfort, but by sustaining it. Abela’s joyful denial of resolution or ease was deliberate yet never alienating, positioning endurance as a central part of the listening experience. What lingered was not a melody, moment, or release, but an awareness of how attention was being held, tested, and repeatedly redirected. The work asked for commitment rather than surrender, rewarding persistence with heightened sensitivity rather than comfort.

_____g.s proved to be a fitting site for this encounter. Its proximity to the street, modest scale, and resistance to polish mirrored the conditions of the performance itself. The space did not insulate the work from the world outside, nor did it soften its edges. Instead, it reinforced the sense that this was an experience unfolding within everyday life, not apart from it, one that demanded presence amid distraction. In an era where listening is often fragmented and mediated, Abela’s performance foregrounded attention as something physical, effortful, and, at times, uncomfortable. It challenged the expectation that engagement should be seamless or immediately gratifying, suggesting instead that sustained focus may require friction. In doing so, the work reframed discomfort not as a barrier to enjoyment, but as a condition through which a different kind of listening might emerge.

Lucas “Granpa” Abela’s performance took place at _____g.s on 22 November 2025.

Footnote:

1. Paul Hegarty, Noise/Music: A History (New York: Continuum, 2007), Introduction, pp. 1–7.

Image credits: Lucas Abela performing at _____g.s, photographed by Joe Rae @convectionpattern.