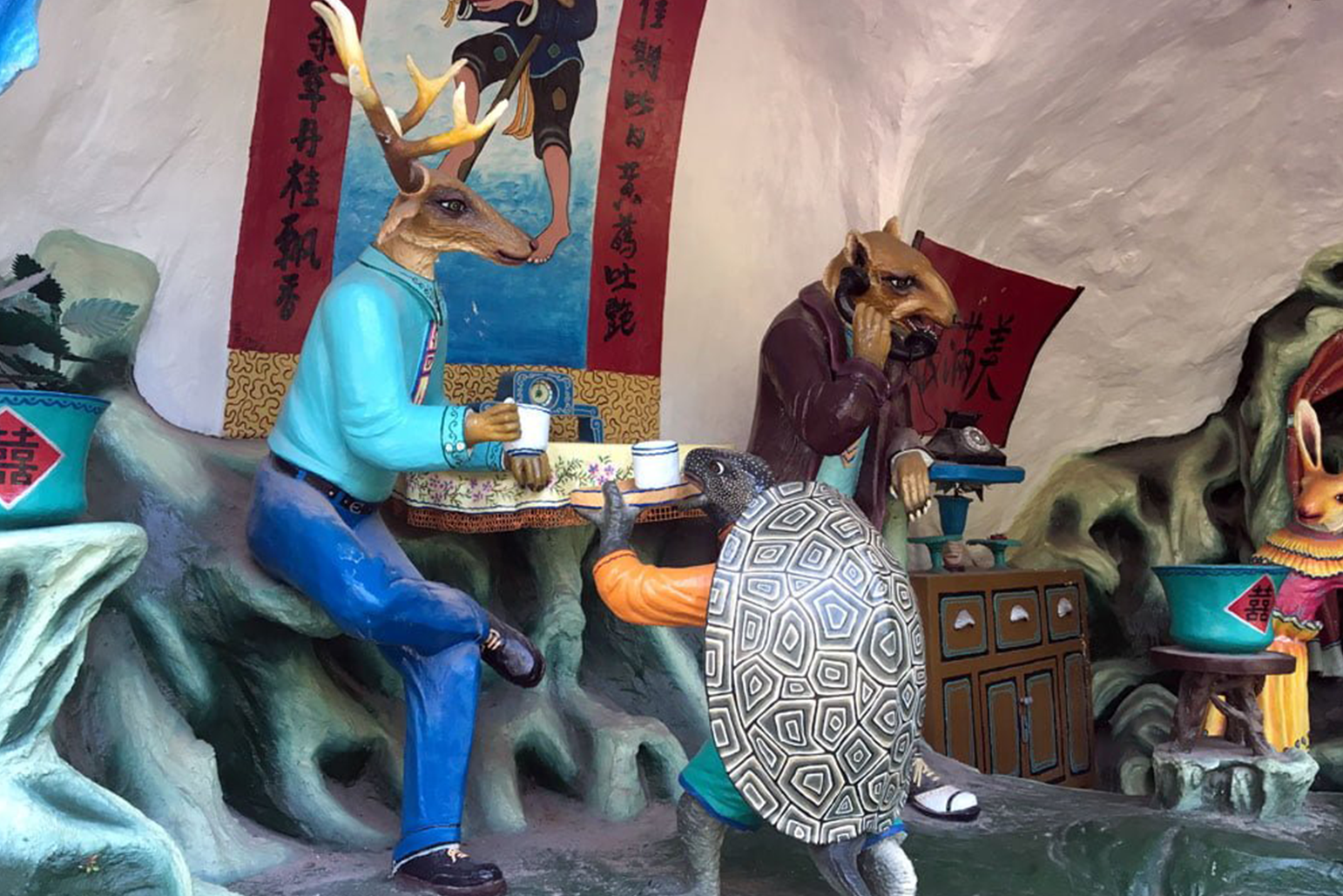

A gaggle of humanoid geese engaged in a domestic dispute, a gory battle between fish-men and warriors, monkeys bearing rifles, and a turtle riding an emu—these are some of the scenes one can expect to encounter when visiting Haw Par Villa in Singapore. However, underneath the absurd collection of over 1000 public sculptures and 150 giant dioramas is a compelling insight into Chinese folklore about death, punishment, and hell that are interlaced with attractions which nod to the park’s unique history and origin.

On arriving at the “theme park”, visitors proceed through the main entrance paifang (a traditional Chinese gateway arch). For us, a group of foreigners, we weren’t quite sure what we were walking into. As we climbed the hill to the first of many outdoor displays, our tour guide informed us that many Gen X and baby boomer Singaporeans, like herself, recall first being brought to the park by their parents to learn about Confucianism. However, she remembers it more vividly as a means of scaring children into good behaviour, intensified by the hellish scenes of violence and punishment that may await in the afterlife. For me, the only reference point to this is sort of horror-surrealism was the infamous psychedelic-boat-ride-through-hell scene in Willy Wonka.

The park was constructed in the late-1930s by Burmese-Chinese millionaire, entrepreneur, and philanthropist Aw Boon Haw, a marketing mogul who rebranded his family’s heat rub product, Ban Yin Yu, as the now famous Tiger Balm. As a side-project to his burgeoning pharmaceutical empire, Aw Boon Haw decided to build a cultural park as a gift for his younger brother and business partner, Aw Boon Par. Haw Par Villa, named after the two brothers (originally titled ‘Tiger Balm Gardens’), was opened to the public in 1937 to serve two purposes: commercial and ideological. The theme park at once marketed the family ointment and served to communicate Confucian ideas and Chinese folklore.

Arriving at the foot of the first of many displays, what becomes immediately apparent is the sheer scale, vibrance, and detail of the more elaborate dioramas—some of which have a tiny jar of the Aw family’s ointment nestled in their hands. The bizarre and cartoonish style of the sculptures begins to make more sense once you become aware of the pharmaceutical tycoon’s aversion to working with blueprints, and his insistence on personally inspecting and meticulously directing the construction of the sculptures himself, despite not having any experience in sculpting. The first display to confront park visitors is a chaotic depiction of a tale from Chinese mythology: the invasion of Neptune’s palace by the Eight Immortals and their battle with the Dragon King of the East Sea with his army of ocean creatures. The bloody scene is held within an unsure structure, half cave and half collapsing wave. Some figures are caught in the surf as they climb to higher ground, while others are positioned on ledges firing harpoons from above. The piece is huge—both physically and with regard to their painterly and sculpturally detailed attention to Chinese folklore. Initially, one is unsure where to look, as the Eight Immortals—each wielding a power that is stored within a vessel instrument used to either destroy evil or bestow life—manifests in a visual onslaught. There is a figure in a frog-suit being attacking another in a fish-costume while being harpooned in the chest. Crabs, turtles, and clams consume some of the more unfortunate warriors. A dual-wielding swordsman emerges from a seashell and a trumpet player rides a stingray like a surfboard across the battlefield. The lack of a concise focal point accentuates the bizarre imagery that is as disorientating as it is transgressive and brutal.

Moving on, it became obvious that we were the only group in the park. Once we were informed about the steady decline of visitors over the years, the ageing sculptures, swathed in explosively vibrant fresh coats of paint, became all the more eerily captivating. As our tour guide took us on a crash-course of Haw Par Villa trivia, a complex narrative of folklore preservation, Confucian ethics, and business venture began to emerge. Shortly after running into a troupe of gorillas (all of them nine to twelve feet tall), followed by a massive crab with a particularly stoked human head which beams at perplexed onlookers from across the grass with a cartoonish grin, you’ll stumble upon what remains of Boon Par’s mansion. Boon Haw built the private estate on the top of the park’s hill as a gift for his younger brother, but Boon Par only lived there for a few years before Japanese troops seized the grounds during their WWII occupation of Singapore (1942– 1945), using it as a lookout for incoming enemy ships in the bay. Following Boon Par’s sudden death in 1944 and the end of the war, Boon Haw returned to Singapore to find the mansion heavily vandalised and decided to tear it down. The vacant brickwork that remains carries a solemn sense of fraternal loss—a sobering scene echoing the remnants of a traumatising era for Singapore and Boon Haw. However, this emotional intermission functions only as a brief detour, as it is is sandwiched between the gorillas and a series of emus being ridden by smaller animals including a frog wearing a baseball cap.

Just down the hill you will reach the main attraction: the infamous ‘Ten Courts of Hell’. It’s an exhibit that’s not for the faint hearted (or faint-stomached). For this displeasure, you’ll have to pay an $18 (SGD) entry fee—a fair price for visiting hell, but one that serves as a final word of caution to any on-the-fence visitors before they enter. Inside is a brooding, dark tunnel featuring ten scenes of torturous punishment that the sinful dead are believed to endure in the afterlife. Each diorama stars a Buddhist Yama or King carrying out judgement on specific crimes, ranging from misusing books and wasting food, to murder and abduction. Depending on their crime, the deceased are sent to a specific court that specialises in its own cleansing form of punishment. There are people being thrown into volcanic pits (for the sin of inflicting physical injury) tied and grilled on red hot copper (for drug addicts and traffickers), crushed under boulders (for neglecting of the old or young) and sinners getting their heart cut out (for the crime of ungratefulness). Yikes. After twenty minutes of wading through the bloodbath, viewers arrive at the tenth court of hell. It features King Zhuanlun, who passes final judgement on the prisoners before they drink from an elderly woman’s cup of magic tea, causing them to forget their past lives. Finally, visitors are presented with the wheel of reincarnation, the process by which prisoners' new lives as either humans or animals are determined based on their behaviour in their previous lives. The experience concludes with a trip to the gift shop to buy a container of tiger balm and marvel at Aw Boon Haw’s bright orange tiger car (it’s exactly what it sounds like), his most flamboyant marketing ploy of all that is parked on permanent display by the exit.

Perhaps it was accentuated by the summer humidity beating down upon us as we crammed in as much of the 8.5 hectare grounds as possible into our schedule, but from our foreigner perspectives, Haw Par Villa signalled something uniquely Singaporean: a combination of ancient Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist moral storytelling made spectacular through vibrant theme park aesthetics, the Aw’s business venture ethos, and the underlying residue of WWII Japanese occupation. The latter two components undoubtedly make for a complicated cultural and historical experience, one that the Aw brothers couldn’t have foreseen playing such dominant roles in how visitors understand the park today. This isn’t to say that the Aw’s exuberant passion for eastern mythology, history, and lore doesn’t translate effectively—the diorama’s allusion to the importance of piety, loyalty, fidelity, charity, judgement in the afterlife, and resisting temptation becomes ferociously apparent once you adjust to the material intensity of the displays. Rather, these themes are wedged in between visuals that allude to the dramatic history of the tiger balm empire and Aw Boon Haw’s lavish taste for the spectacular, making for an unconventional pairing of ancient spiritual values with modern private enterprise. The outcome is a confronting, occasionally perplexing yet undoubtedly mesmerising window into a wild business venture that manages to pull off a highly theatrical 20th century animation of Chinese mythology. Suffice to say, Haw Par Villa is the weirdest tourist art attraction that I’ve encountered. However, it is a must-see (or rather, must-experience) Singaporean treasure that is sure to spark your curiosity, make your eyes water, bring your children to tears and inadvertently have you silently mouthing to yourself “what the fuck”.

Haw Par Villa, 262 Pasir Panjang Road, Singapore.

Image credits:

1. Choo Yut Shing, “The Eight Immortals #4,” Uploaded April 30, 2014.

2. Jaclynn Seah, “Haw Par Villa – Singapore’s weirdest park about Chinese culture,” Uploaded March 27, 2014.

3. “Haw Par Villa – Unusual Singapore Theme Park,” Uploaded October 15, 2017.

4. “Haw Par Villa – Unusual Singapore Theme Park,” Uploaded October 15, 2017.

5. Jaclynn Seah, “Haw Par Villa – Singapore’s weirdest park about Chinese culture,” Uploaded March 27, 2014.

On arriving at the “theme park”, visitors proceed through the main entrance paifang (a traditional Chinese gateway arch). For us, a group of foreigners, we weren’t quite sure what we were walking into. As we climbed the hill to the first of many outdoor displays, our tour guide informed us that many Gen X and baby boomer Singaporeans, like herself, recall first being brought to the park by their parents to learn about Confucianism. However, she remembers it more vividly as a means of scaring children into good behaviour, intensified by the hellish scenes of violence and punishment that may await in the afterlife. For me, the only reference point to this is sort of horror-surrealism was the infamous psychedelic-boat-ride-through-hell scene in Willy Wonka.

The park was constructed in the late-1930s by Burmese-Chinese millionaire, entrepreneur, and philanthropist Aw Boon Haw, a marketing mogul who rebranded his family’s heat rub product, Ban Yin Yu, as the now famous Tiger Balm. As a side-project to his burgeoning pharmaceutical empire, Aw Boon Haw decided to build a cultural park as a gift for his younger brother and business partner, Aw Boon Par. Haw Par Villa, named after the two brothers (originally titled ‘Tiger Balm Gardens’), was opened to the public in 1937 to serve two purposes: commercial and ideological. The theme park at once marketed the family ointment and served to communicate Confucian ideas and Chinese folklore.

Arriving at the foot of the first of many displays, what becomes immediately apparent is the sheer scale, vibrance, and detail of the more elaborate dioramas—some of which have a tiny jar of the Aw family’s ointment nestled in their hands. The bizarre and cartoonish style of the sculptures begins to make more sense once you become aware of the pharmaceutical tycoon’s aversion to working with blueprints, and his insistence on personally inspecting and meticulously directing the construction of the sculptures himself, despite not having any experience in sculpting. The first display to confront park visitors is a chaotic depiction of a tale from Chinese mythology: the invasion of Neptune’s palace by the Eight Immortals and their battle with the Dragon King of the East Sea with his army of ocean creatures. The bloody scene is held within an unsure structure, half cave and half collapsing wave. Some figures are caught in the surf as they climb to higher ground, while others are positioned on ledges firing harpoons from above. The piece is huge—both physically and with regard to their painterly and sculpturally detailed attention to Chinese folklore. Initially, one is unsure where to look, as the Eight Immortals—each wielding a power that is stored within a vessel instrument used to either destroy evil or bestow life—manifests in a visual onslaught. There is a figure in a frog-suit being attacking another in a fish-costume while being harpooned in the chest. Crabs, turtles, and clams consume some of the more unfortunate warriors. A dual-wielding swordsman emerges from a seashell and a trumpet player rides a stingray like a surfboard across the battlefield. The lack of a concise focal point accentuates the bizarre imagery that is as disorientating as it is transgressive and brutal.

Moving on, it became obvious that we were the only group in the park. Once we were informed about the steady decline of visitors over the years, the ageing sculptures, swathed in explosively vibrant fresh coats of paint, became all the more eerily captivating. As our tour guide took us on a crash-course of Haw Par Villa trivia, a complex narrative of folklore preservation, Confucian ethics, and business venture began to emerge. Shortly after running into a troupe of gorillas (all of them nine to twelve feet tall), followed by a massive crab with a particularly stoked human head which beams at perplexed onlookers from across the grass with a cartoonish grin, you’ll stumble upon what remains of Boon Par’s mansion. Boon Haw built the private estate on the top of the park’s hill as a gift for his younger brother, but Boon Par only lived there for a few years before Japanese troops seized the grounds during their WWII occupation of Singapore (1942– 1945), using it as a lookout for incoming enemy ships in the bay. Following Boon Par’s sudden death in 1944 and the end of the war, Boon Haw returned to Singapore to find the mansion heavily vandalised and decided to tear it down. The vacant brickwork that remains carries a solemn sense of fraternal loss—a sobering scene echoing the remnants of a traumatising era for Singapore and Boon Haw. However, this emotional intermission functions only as a brief detour, as it is is sandwiched between the gorillas and a series of emus being ridden by smaller animals including a frog wearing a baseball cap.

Just down the hill you will reach the main attraction: the infamous ‘Ten Courts of Hell’. It’s an exhibit that’s not for the faint hearted (or faint-stomached). For this displeasure, you’ll have to pay an $18 (SGD) entry fee—a fair price for visiting hell, but one that serves as a final word of caution to any on-the-fence visitors before they enter. Inside is a brooding, dark tunnel featuring ten scenes of torturous punishment that the sinful dead are believed to endure in the afterlife. Each diorama stars a Buddhist Yama or King carrying out judgement on specific crimes, ranging from misusing books and wasting food, to murder and abduction. Depending on their crime, the deceased are sent to a specific court that specialises in its own cleansing form of punishment. There are people being thrown into volcanic pits (for the sin of inflicting physical injury) tied and grilled on red hot copper (for drug addicts and traffickers), crushed under boulders (for neglecting of the old or young) and sinners getting their heart cut out (for the crime of ungratefulness). Yikes. After twenty minutes of wading through the bloodbath, viewers arrive at the tenth court of hell. It features King Zhuanlun, who passes final judgement on the prisoners before they drink from an elderly woman’s cup of magic tea, causing them to forget their past lives. Finally, visitors are presented with the wheel of reincarnation, the process by which prisoners' new lives as either humans or animals are determined based on their behaviour in their previous lives. The experience concludes with a trip to the gift shop to buy a container of tiger balm and marvel at Aw Boon Haw’s bright orange tiger car (it’s exactly what it sounds like), his most flamboyant marketing ploy of all that is parked on permanent display by the exit.

Perhaps it was accentuated by the summer humidity beating down upon us as we crammed in as much of the 8.5 hectare grounds as possible into our schedule, but from our foreigner perspectives, Haw Par Villa signalled something uniquely Singaporean: a combination of ancient Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist moral storytelling made spectacular through vibrant theme park aesthetics, the Aw’s business venture ethos, and the underlying residue of WWII Japanese occupation. The latter two components undoubtedly make for a complicated cultural and historical experience, one that the Aw brothers couldn’t have foreseen playing such dominant roles in how visitors understand the park today. This isn’t to say that the Aw’s exuberant passion for eastern mythology, history, and lore doesn’t translate effectively—the diorama’s allusion to the importance of piety, loyalty, fidelity, charity, judgement in the afterlife, and resisting temptation becomes ferociously apparent once you adjust to the material intensity of the displays. Rather, these themes are wedged in between visuals that allude to the dramatic history of the tiger balm empire and Aw Boon Haw’s lavish taste for the spectacular, making for an unconventional pairing of ancient spiritual values with modern private enterprise. The outcome is a confronting, occasionally perplexing yet undoubtedly mesmerising window into a wild business venture that manages to pull off a highly theatrical 20th century animation of Chinese mythology. Suffice to say, Haw Par Villa is the weirdest tourist art attraction that I’ve encountered. However, it is a must-see (or rather, must-experience) Singaporean treasure that is sure to spark your curiosity, make your eyes water, bring your children to tears and inadvertently have you silently mouthing to yourself “what the fuck”.

Haw Par Villa, 262 Pasir Panjang Road, Singapore.

Image credits:

1. Choo Yut Shing, “The Eight Immortals #4,” Uploaded April 30, 2014.

2. Jaclynn Seah, “Haw Par Villa – Singapore’s weirdest park about Chinese culture,” Uploaded March 27, 2014.

3. “Haw Par Villa – Unusual Singapore Theme Park,” Uploaded October 15, 2017.

4. “Haw Par Villa – Unusual Singapore Theme Park,” Uploaded October 15, 2017.

5. Jaclynn Seah, “Haw Par Villa – Singapore’s weirdest park about Chinese culture,” Uploaded March 27, 2014.