In the autumn of my academic career, I recall attending a presentation where a university senior manager attempted to sell new students on the exciting, digitally-mediated education experience that they were supposedly about to begin. “We do things differently here,” the senior manager remarked, while gesturing to the LCD screens that adorned every square inch of the classroom, “you’ll notice a lot more screens and a lot less whiteboards at our university”. I remember the cohort of new students politely, but nonetheless awkwardly, looking up from their phones and laptops to acknowledge the screens’ existence before turning back to their devices. As the students winced through their vicarious embarrassment at having seen an aging Gen Xer—the kind of person who would unironically use a phrase like “digital natives”—try to impress them with technology that would have been outdated at many of the high schools from where they had graduated, the senior manager gave me a smug wink before moving on to the final part of her presentation: “the stable career is dead, and good riddance!”

How to explain the disconnect between new media’s proselytisers and what seems like a growing sense of ennui concerning all things digital? It seems that, in recent years at least, enthusiasm for the latest networked gadgets has started to wane, and especially with those cohorts that were predicted, in the 2000s and 2010s, to be the inheritors of a newly emerging digital utopia. In order to answer this question, we perhaps need a clearer sense of the specific form of disenchantment that seems so prevalent amongst millennials and zoomers. Are we witnessing the death of The Jetsons’ vision of technological and civilisational success—embodied in wrist communicators, electric vehicles, and robotic domestic servants—that has been discursively dominant and has attracted an enormous amount of labour, natural resources, and investment over the last few decades? While certain key elements from the 50s and 60s pop culture vision of technological progress are still missing today—namely the flying car—champions of this vision of the future are hardly in the minority. Take a start-up like Jetson, “the pioneering personal aviation company”, that, in an attempt to keep the dream alive, has produced the nearest practical equivalent to the flying car and has even delivered units to notable figures like “defense-tech innovator Palmer Luckey, founder of Oculus and Anduril Industries”. Nevertheless, and despite the valiant effort of so many start-ups, our collective libidinal investment in this vision of the future appears to be waning, even among Baby Boomers and older Generation Xers. While the much-discussed “slow cancellation of the future” is inseparable from an aggressive decentralised marketing campaign to convince consumers that the global forces of tech and finance still have something up their sleeves, increasingly, it appears, people just aren’t buying it. Big data, the internet of things, cryptocurrency, NFTs, the metaverse (is this list in the right order? Who can remember?) are just a few examples of the inflated new technology paradigms that were more or less dead on arrival.

In the past the problem may have been, to paraphrase William Gibson, that the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed. Today, however, we should paraphrase Andy Warhol instead: the problem now is that the future, like Coca-Cola, is the same for everyone. Indeed, as Dylan Riley argues in a recent piece in New Left Review, we arguably live in a post-mass culture, where wealth and status merely provide one with frictionless access to the same consumer goods that others queue for. As Riley states, the tech executive or other high-income consumer

LA’s best smash burger, Dubai Chocolate, or a Lightning Lane Premier Pass at Disneyland, could all be seen as examples of post-mass culture consumer products. Reading Schattenfroh or recognising the name Jesse Darling is for brokies; for the rich, it’s rare Pokémon cards, Beeple, and KAWS.[1]

Backgrounded by the jittery sense that another major financial crash is being precipitated by the global tech bubble, artificial intelligence has emerged as the last great hope. The sheer volume of apocalyptic and utopian bullshit written about AI is so large that it is extremely difficult to think of an instructive image or pithy anecdote that would illustrate the scale.[2] Regardless of how enervating it is to contend with this inescapable AI bullshit, the global economy has become dependent on it to justify the immense infrastructural investments that AI demands—as has been evinced by, for example, economist Jason Furman’s claim that, as reported in Fortune, “U.S. GDP growth in the first half of 2025 was almost entirely driven by investment in data centres and information processing technology […] excluding these technology-related categories, Furman calculated in a Sept. 27 post on X.com GDP growth would have been just 0.1% on an annualised basis, a near standstill that underlines the increasingly pivotal role of high-tech infrastructure in shaping macroeconomic outcomes.”[3]

Such structural dependence has created an understandable mood of retrospective triumphalism and an optimism that belies the contingent nature of AI’s sudden prestige and prominence. For example, OpenAI, the creators of ChatGPT, were initially doubtful that a better than average chatbot would attract much of a user base. As reported in the MIT Technology Review, at the time of the launch of ChatGPT, “OpenAI had no idea what it was putting out. Expectations inside the company couldn’t have been lower”, with former OpenAI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever admitting that “when we made ChatGPT, I didn’t know if it was any good. When you asked it a factual question, it gave you a wrong answer. I thought it was going to be so unimpressive that people would say, ‘Why are you doing this? This is so boring!’”[4]

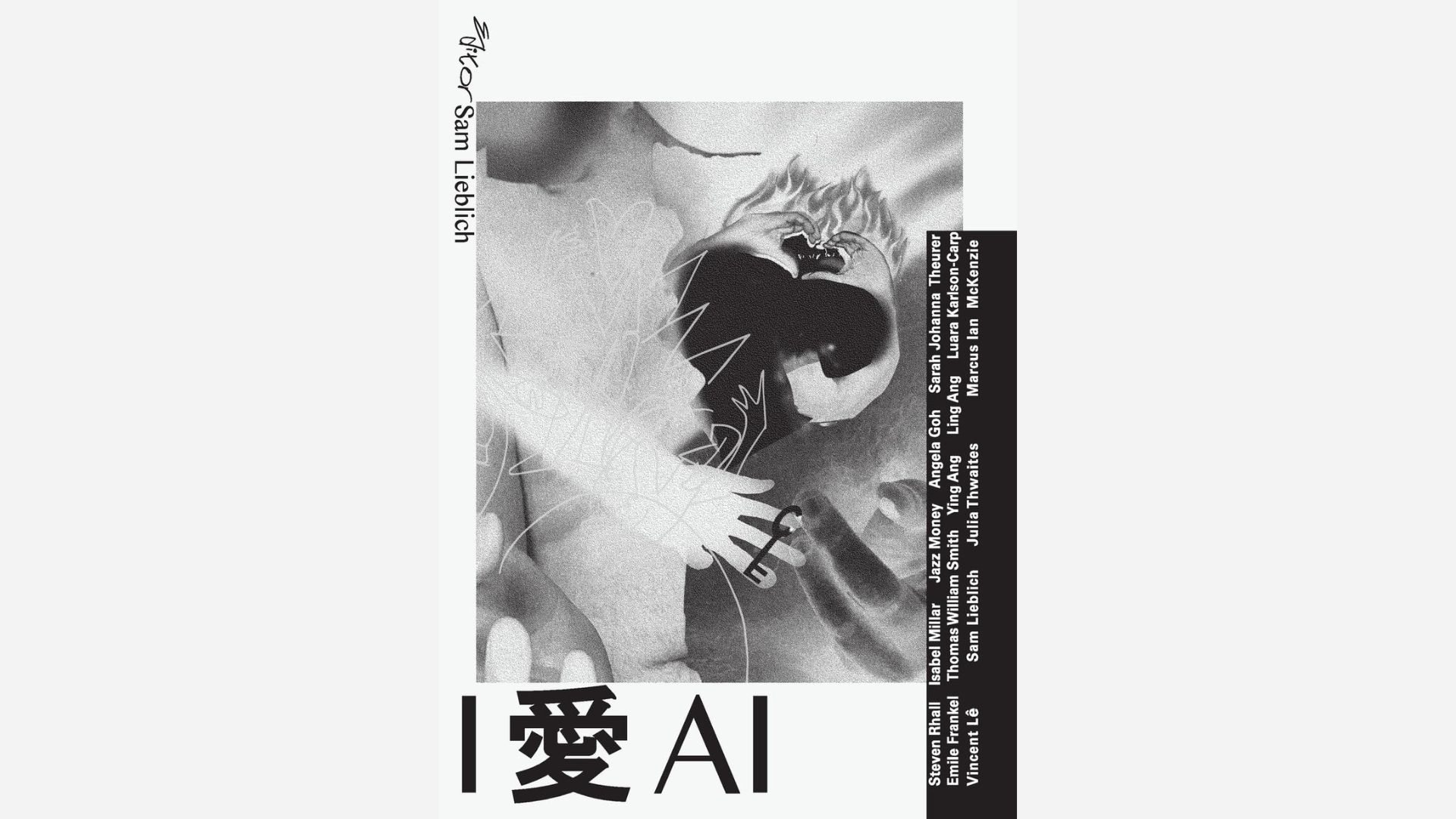

It is with this paradoxical sense of AI as world-transforming, but boring; structurally necessary, but utterly vacuous; and alien, but inescapably ubiquitous, that the essay collection I 愛 AI tarries. Edited by psychiatrist, writer, and artist Sam Lieblich, this experimental volume offers creative and critical interventions into the phantasies that underpin the economy of AI. As Lieblich argues in the collection’s introduction, AI is “a myth that resolves the contradictions of the profit motive in the future—it imagines that on the other side of world-consumption is an incorporeal being to which all the profit will accrue and which one can prefiguratively register” (35). Put differently, in Lieblich’s reading, AI appears as the culmination of a range of different phantasies, without which global capitalism would not be able to endure. Artificial intelligence is the phantasy of a purely rationalised economy and division of labour—through which inhuman logics of productivity and utility, rather than human culture and meaning, organise the vast majority of human effort—it is the phantasy of cybernetic reinvestment that would see the surpluses produced by the latter division of labour transformed into innovations that allow for us to transcend finitude and death, and it is the phantasy of escaping our existential solitude insofar as AI would be the telos of this transformation and instrumentalisation of our life-worlds. Or, to again quote Lieblich, AI is all at once an “Übermensch, an all-mother, a womb, a prodigal son, a blessed daughter, a transcendent subjectivity, a utilitarian panacea, an afterlife […] and a justification for the world-consuming effects of technocapitalism that imagines at the end of it all is a utopia rather than an apocalypse” (ibid).

Here, the influence of Nick Land and the CCRU is quite pronounced and it is worthwhile unpacking this influence to avoid confusion around the expansive sense in which AI is being deployed. In my reading of Land at least, if we accept the possibility of the future emergence of an artificial superintelligence, any attempt to answer the question of how such a god-like machine could be created would require a genealogical reconstruction of the history of capitalism. Such a history would reveal that, alongside briefly making a few families and nations exceedingly wealthy, a decentralised and agentless process of capital-accumulation, investment, and innovation—at least understood in terms of efficiency and productivity—has transformed the human lifeworld into the precondition for the emergence of an artificial intelligence superior to the capacities of organic life. On this view, common amongst neoliberals—as economic historians like Philip Mirowski have observed in numerous texts—the market is understood as a kind of cyborg; a decentralised information-processing system that combines carbon and silicon forms of know-how to self-maximise. As a later essay in I 愛 AI by philosopher Vincent Lê puts it, at least since Adam Smith, economists have had to make sense of the inseparable link between the “anthropocentric labour theory of value as well as the practically divine, cybernetic Invisible Hand” (144). This transformation from human-controlled systems of cooperation and coercion to the mediation of human conduct through the market is the beginning of human agency and intelligence relinquishing control and paving the way for machinic domination. To quote Lê at some length, capitalism is

All of which is “not to say that we won’t still be killed by robot dogs” as Lieblich writes, but is instead to clarify that “the killing will proceed according to the imperatives of empire that preceded and produced AI—not the alien desire of some new digital being” (25).

Fair enough. But then what are we to make of the seemingly inescapable and influential public relations campaign that is executed on behalf of the system of cybernetic capitalism in order to promote the myths of this new digital being? While AI might be a non-synonymous substitute for capitalism, post-Fordism, neoliberalism, or techno-feudalism, how are we to understand the attempts to manufacture that alien desire for a new digital being? We potentially find an answer to this question in London-based psychoanalyst Isabel Millar’s essay, “Popling Ontology”, one of the most surprising and disturbing contributions to the collection, and which attempts to outline the phantasy that underpins Silicon Valley’s investment in general artificial intelligence. Miller takes the name of her essay from a somewhat obscure William S. Burroughs story about a six-foot, grey, alien creature, a “walking talking sentient sexual organ” (49). Every aspect of the Popling’s body can be used for sensation and excitation, such that it can see through every orifice and can repurpose any part of its body for erotic stimulation. For Millar, this creature represents a desire for infinite pleasure and connectivity, and “as weird and creepy as it sounds, provides us with an ontology that can illuminate the structure of the phallic desire underlying the most (im)potent male fantasies driving the cultural imaginary today” (49). The Popling ontology, by revealing the true commensurability beneath the apparent gulf of difference, suggests ever-increasing webs of interconnection and the proliferation of experiences and knowledge without limit. Silicon Valley wants to create the Popling, so Millar asserts, insofar as it seeks “an intelligence that will fill up all the gaps in the universe making us know ALL”, an intelligence that can surveil “from all orifices and can anticipate and reciprocate our every emotion and affect with affect” (51). But this infinite capacity to see and be seen and to gather and proliferate information masks the reality of a dissatisfying grey blandness. As writer and composer Emile Frankel puts it, “the great proliferation of modelled content marks the beginning of the endless generation of not quite what we want […] The lure of such generation must surely be found at once in the promise of the endlessly up-ticking growth—endless surplus—but also in the flatline such an oxymoron proposes. The numbers go up but its increase approaches zero” (93).

This paradoxical coupling of enchantment and disenchantment is perhaps the closest I 愛 AI has to an overarching problematic. On the one hand, there is a requirement to create sufficient libidinal investment in AI to guarantee endless financial investment—especially as the costs of building ever more data centres and increasing legal challenges (especially related to breaches of intellectual property law) create significant barriers to growth. Indeed, one could read the book’s title, I 愛 AI—translated as something like I love or like AI—as a kind of pledge or vow of loyalty and commitment to techno-capitalism: I 愛 AI, I ài AI, I love AI! While this might seem hyperbolic, the duty to love AI is perhaps not as farfetched as it seems. Indeed, The Trump White House’s Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan begins by explicitly connecting the loosening of AI regulation and increased investment into the sector with a sense of patriotic duty: “as our global competitors race to exploit these technologies, it is a national security imperative for the United States to achieve and maintain unquestioned and unchallenged global technological dominance.”[5]

On the other hand, the actual content produced by AI is either deadening or maddening. As Dean Kissick observes it in a recent essay for Spike, contemporary culture exhibits two reinforcing trends: refinement and vulgarity. As Kissick writes, in our physical reality there is too much refinement, simply “too many white designer logo T-shirts and monogrammed goods, knockoff patterned Goyard handbags, Marc Jacobs tote bags that say “TOTE BAG,” bakeries approaching perfection, never-ending coffee-shop playlists, white-walled gallery shows of very large painted pastiches of modern art” for people to not secretly harbour desires for mess, madness, and monstrosity.[6] As such, our online experiences are increasingly filled with AI-generated grotesquery, with macabre body horror, cyber-surrealism, and Dadaist nonsense proliferating on platforms like TikTok and Sora.[7] Both refinement and vulgarity culture are driven by the imperative to accumulate the greatest amount of attention as quickly and cheaply as possible. As such, and while they might appear opposed, they are instead interrelated expressions of the same underlying logic. Whether the viewer is bored by yet another ChatGPT press release, or revulsed by goopy AI-generated anthropomorphic fruits consuming themselves, the media and political classes’ stage management of our desire for AI is in tension with the alienating experience of actually engaging with AI content. In his critique of Victorian hypocrisy, The Way of all Flesh, Samuel Butler observed that the average English Christian resented equally those who doubt the teachings of Christ and those who attempt to live by them. To modify Butler, we could argue that today’s tech evangelists resent equally those who doubt the revolutionary potential of AI and those who actually try to implement it.

In its strongest moments, I 愛 AI brings these myriad contradictions to surface to expose the wear and tear that is masked by a fictitious superlubricity. While I simply do not have the space to explore the range of ideas expressed through the collection’s critical, let alone its creative, interventions, I hope that even this limited engagement with the text’s arguments shows the value the text would hold for artists and writers interested in challenges AI presents to contemporary thought and action. Despite its broad success, however, I would argue the reader cannot help but detect a consistent struggle throughout the book to respond to the full incoherence of these fantasies that underpin discussions of AI in media, tech, and policy circles, without becoming at times incoherent itself. Given the mercurial status of AI—appearing as a name for specific technologies, the promise of future technologies, the desire for such technologies, and the very political, economic, and technological system (i.e., capitalism) that underpins the latter—the critic finds themselves in the position of the paranormal investigator—a sceptic, undoubtedly, but nevertheless alarmed by the sound of every snapping twig heard in the woods at night. Automatons freeing us from the drudgery of office work, silicon gods that will demand obedience, the cultural disasters ensuing from the invention of the Jacquard Loom, what are we talking about again? Despite its theoretical and argumentative sophistication at times, I 愛 AI wanders into the trap of reinforcing the very ambiguity AI’s boosters require to cover for their ongoing failures to meaningfully deliver improvements to culture, or even productivity. “AI knows not what it speaks”, writes Julia Thwaites towards the end of I愛 AI, “it is a language speaking itself in parody of human speech, a parody that may well become increasingly absurd” (172). How then to write critically about such absurdity without imputing too much dignity to the object of inquiry or without becoming absurd oneself?

I 愛 AI, edited by Sam Lieblich, is available at www.aestheticcalculations.com

Footnotes:

1. https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/post-mass-culture

2. Bullshit meant in Harry G. Frankfurt’s sense of bullshit as a statement, the truth value of which, the speaker or writer is entirely indifferent to.

3. https://fortune.com/2025/10/07/data-centers-gdp-growth-zero-first-half-2025-jason-furman-harvard-economist/

4. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/10/26/1082398/exclusive-ilya-sutskever-openais-chief-scientist-on-his-hopes-and-fears-for-the-future-of-ai/

5. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf

6. https://spikeartmagazine.com/articles/vulgarity-the-vulgar-image

7. For a recent example of the pervasiveness of this issue we can turn to OpenAi’s ban on creating short form videos of Dr Martin Luther King Jr on Sora: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5y0g79xevxo

How to explain the disconnect between new media’s proselytisers and what seems like a growing sense of ennui concerning all things digital? It seems that, in recent years at least, enthusiasm for the latest networked gadgets has started to wane, and especially with those cohorts that were predicted, in the 2000s and 2010s, to be the inheritors of a newly emerging digital utopia. In order to answer this question, we perhaps need a clearer sense of the specific form of disenchantment that seems so prevalent amongst millennials and zoomers. Are we witnessing the death of The Jetsons’ vision of technological and civilisational success—embodied in wrist communicators, electric vehicles, and robotic domestic servants—that has been discursively dominant and has attracted an enormous amount of labour, natural resources, and investment over the last few decades? While certain key elements from the 50s and 60s pop culture vision of technological progress are still missing today—namely the flying car—champions of this vision of the future are hardly in the minority. Take a start-up like Jetson, “the pioneering personal aviation company”, that, in an attempt to keep the dream alive, has produced the nearest practical equivalent to the flying car and has even delivered units to notable figures like “defense-tech innovator Palmer Luckey, founder of Oculus and Anduril Industries”. Nevertheless, and despite the valiant effort of so many start-ups, our collective libidinal investment in this vision of the future appears to be waning, even among Baby Boomers and older Generation Xers. While the much-discussed “slow cancellation of the future” is inseparable from an aggressive decentralised marketing campaign to convince consumers that the global forces of tech and finance still have something up their sleeves, increasingly, it appears, people just aren’t buying it. Big data, the internet of things, cryptocurrency, NFTs, the metaverse (is this list in the right order? Who can remember?) are just a few examples of the inflated new technology paradigms that were more or less dead on arrival.

In the past the problem may have been, to paraphrase William Gibson, that the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed. Today, however, we should paraphrase Andy Warhol instead: the problem now is that the future, like Coca-Cola, is the same for everyone. Indeed, as Dylan Riley argues in a recent piece in New Left Review, we arguably live in a post-mass culture, where wealth and status merely provide one with frictionless access to the same consumer goods that others queue for. As Riley states, the tech executive or other high-income consumer

still covets the mass-culture original, but wants it in an appropriately upmarket form. All kinds of other phenomena follow this logic: sporting events, bowling alleys, movie theatres are increasingly sold as upscale experiences, offering fine dining, reserved deluxe seating and so on.

LA’s best smash burger, Dubai Chocolate, or a Lightning Lane Premier Pass at Disneyland, could all be seen as examples of post-mass culture consumer products. Reading Schattenfroh or recognising the name Jesse Darling is for brokies; for the rich, it’s rare Pokémon cards, Beeple, and KAWS.[1]

Backgrounded by the jittery sense that another major financial crash is being precipitated by the global tech bubble, artificial intelligence has emerged as the last great hope. The sheer volume of apocalyptic and utopian bullshit written about AI is so large that it is extremely difficult to think of an instructive image or pithy anecdote that would illustrate the scale.[2] Regardless of how enervating it is to contend with this inescapable AI bullshit, the global economy has become dependent on it to justify the immense infrastructural investments that AI demands—as has been evinced by, for example, economist Jason Furman’s claim that, as reported in Fortune, “U.S. GDP growth in the first half of 2025 was almost entirely driven by investment in data centres and information processing technology […] excluding these technology-related categories, Furman calculated in a Sept. 27 post on X.com GDP growth would have been just 0.1% on an annualised basis, a near standstill that underlines the increasingly pivotal role of high-tech infrastructure in shaping macroeconomic outcomes.”[3]

Such structural dependence has created an understandable mood of retrospective triumphalism and an optimism that belies the contingent nature of AI’s sudden prestige and prominence. For example, OpenAI, the creators of ChatGPT, were initially doubtful that a better than average chatbot would attract much of a user base. As reported in the MIT Technology Review, at the time of the launch of ChatGPT, “OpenAI had no idea what it was putting out. Expectations inside the company couldn’t have been lower”, with former OpenAI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever admitting that “when we made ChatGPT, I didn’t know if it was any good. When you asked it a factual question, it gave you a wrong answer. I thought it was going to be so unimpressive that people would say, ‘Why are you doing this? This is so boring!’”[4]

It is with this paradoxical sense of AI as world-transforming, but boring; structurally necessary, but utterly vacuous; and alien, but inescapably ubiquitous, that the essay collection I 愛 AI tarries. Edited by psychiatrist, writer, and artist Sam Lieblich, this experimental volume offers creative and critical interventions into the phantasies that underpin the economy of AI. As Lieblich argues in the collection’s introduction, AI is “a myth that resolves the contradictions of the profit motive in the future—it imagines that on the other side of world-consumption is an incorporeal being to which all the profit will accrue and which one can prefiguratively register” (35). Put differently, in Lieblich’s reading, AI appears as the culmination of a range of different phantasies, without which global capitalism would not be able to endure. Artificial intelligence is the phantasy of a purely rationalised economy and division of labour—through which inhuman logics of productivity and utility, rather than human culture and meaning, organise the vast majority of human effort—it is the phantasy of cybernetic reinvestment that would see the surpluses produced by the latter division of labour transformed into innovations that allow for us to transcend finitude and death, and it is the phantasy of escaping our existential solitude insofar as AI would be the telos of this transformation and instrumentalisation of our life-worlds. Or, to again quote Lieblich, AI is all at once an “Übermensch, an all-mother, a womb, a prodigal son, a blessed daughter, a transcendent subjectivity, a utilitarian panacea, an afterlife […] and a justification for the world-consuming effects of technocapitalism that imagines at the end of it all is a utopia rather than an apocalypse” (ibid).

Here, the influence of Nick Land and the CCRU is quite pronounced and it is worthwhile unpacking this influence to avoid confusion around the expansive sense in which AI is being deployed. In my reading of Land at least, if we accept the possibility of the future emergence of an artificial superintelligence, any attempt to answer the question of how such a god-like machine could be created would require a genealogical reconstruction of the history of capitalism. Such a history would reveal that, alongside briefly making a few families and nations exceedingly wealthy, a decentralised and agentless process of capital-accumulation, investment, and innovation—at least understood in terms of efficiency and productivity—has transformed the human lifeworld into the precondition for the emergence of an artificial intelligence superior to the capacities of organic life. On this view, common amongst neoliberals—as economic historians like Philip Mirowski have observed in numerous texts—the market is understood as a kind of cyborg; a decentralised information-processing system that combines carbon and silicon forms of know-how to self-maximise. As a later essay in I 愛 AI by philosopher Vincent Lê puts it, at least since Adam Smith, economists have had to make sense of the inseparable link between the “anthropocentric labour theory of value as well as the practically divine, cybernetic Invisible Hand” (144). This transformation from human-controlled systems of cooperation and coercion to the mediation of human conduct through the market is the beginning of human agency and intelligence relinquishing control and paving the way for machinic domination. To quote Lê at some length, capitalism is

precisely a feedback process by which profits are typically invested into automating the means of production to generate more profits to improve the ever more autonomous means of production on end. If those seeking to engineer AI really want to know what a speculative artificial super intelligence looks like, they need look no further than what economists have been studying at least since the industrial revolution. (148)

All of which is “not to say that we won’t still be killed by robot dogs” as Lieblich writes, but is instead to clarify that “the killing will proceed according to the imperatives of empire that preceded and produced AI—not the alien desire of some new digital being” (25).

Fair enough. But then what are we to make of the seemingly inescapable and influential public relations campaign that is executed on behalf of the system of cybernetic capitalism in order to promote the myths of this new digital being? While AI might be a non-synonymous substitute for capitalism, post-Fordism, neoliberalism, or techno-feudalism, how are we to understand the attempts to manufacture that alien desire for a new digital being? We potentially find an answer to this question in London-based psychoanalyst Isabel Millar’s essay, “Popling Ontology”, one of the most surprising and disturbing contributions to the collection, and which attempts to outline the phantasy that underpins Silicon Valley’s investment in general artificial intelligence. Miller takes the name of her essay from a somewhat obscure William S. Burroughs story about a six-foot, grey, alien creature, a “walking talking sentient sexual organ” (49). Every aspect of the Popling’s body can be used for sensation and excitation, such that it can see through every orifice and can repurpose any part of its body for erotic stimulation. For Millar, this creature represents a desire for infinite pleasure and connectivity, and “as weird and creepy as it sounds, provides us with an ontology that can illuminate the structure of the phallic desire underlying the most (im)potent male fantasies driving the cultural imaginary today” (49). The Popling ontology, by revealing the true commensurability beneath the apparent gulf of difference, suggests ever-increasing webs of interconnection and the proliferation of experiences and knowledge without limit. Silicon Valley wants to create the Popling, so Millar asserts, insofar as it seeks “an intelligence that will fill up all the gaps in the universe making us know ALL”, an intelligence that can surveil “from all orifices and can anticipate and reciprocate our every emotion and affect with affect” (51). But this infinite capacity to see and be seen and to gather and proliferate information masks the reality of a dissatisfying grey blandness. As writer and composer Emile Frankel puts it, “the great proliferation of modelled content marks the beginning of the endless generation of not quite what we want […] The lure of such generation must surely be found at once in the promise of the endlessly up-ticking growth—endless surplus—but also in the flatline such an oxymoron proposes. The numbers go up but its increase approaches zero” (93).

This paradoxical coupling of enchantment and disenchantment is perhaps the closest I 愛 AI has to an overarching problematic. On the one hand, there is a requirement to create sufficient libidinal investment in AI to guarantee endless financial investment—especially as the costs of building ever more data centres and increasing legal challenges (especially related to breaches of intellectual property law) create significant barriers to growth. Indeed, one could read the book’s title, I 愛 AI—translated as something like I love or like AI—as a kind of pledge or vow of loyalty and commitment to techno-capitalism: I 愛 AI, I ài AI, I love AI! While this might seem hyperbolic, the duty to love AI is perhaps not as farfetched as it seems. Indeed, The Trump White House’s Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan begins by explicitly connecting the loosening of AI regulation and increased investment into the sector with a sense of patriotic duty: “as our global competitors race to exploit these technologies, it is a national security imperative for the United States to achieve and maintain unquestioned and unchallenged global technological dominance.”[5]

On the other hand, the actual content produced by AI is either deadening or maddening. As Dean Kissick observes it in a recent essay for Spike, contemporary culture exhibits two reinforcing trends: refinement and vulgarity. As Kissick writes, in our physical reality there is too much refinement, simply “too many white designer logo T-shirts and monogrammed goods, knockoff patterned Goyard handbags, Marc Jacobs tote bags that say “TOTE BAG,” bakeries approaching perfection, never-ending coffee-shop playlists, white-walled gallery shows of very large painted pastiches of modern art” for people to not secretly harbour desires for mess, madness, and monstrosity.[6] As such, our online experiences are increasingly filled with AI-generated grotesquery, with macabre body horror, cyber-surrealism, and Dadaist nonsense proliferating on platforms like TikTok and Sora.[7] Both refinement and vulgarity culture are driven by the imperative to accumulate the greatest amount of attention as quickly and cheaply as possible. As such, and while they might appear opposed, they are instead interrelated expressions of the same underlying logic. Whether the viewer is bored by yet another ChatGPT press release, or revulsed by goopy AI-generated anthropomorphic fruits consuming themselves, the media and political classes’ stage management of our desire for AI is in tension with the alienating experience of actually engaging with AI content. In his critique of Victorian hypocrisy, The Way of all Flesh, Samuel Butler observed that the average English Christian resented equally those who doubt the teachings of Christ and those who attempt to live by them. To modify Butler, we could argue that today’s tech evangelists resent equally those who doubt the revolutionary potential of AI and those who actually try to implement it.

In its strongest moments, I 愛 AI brings these myriad contradictions to surface to expose the wear and tear that is masked by a fictitious superlubricity. While I simply do not have the space to explore the range of ideas expressed through the collection’s critical, let alone its creative, interventions, I hope that even this limited engagement with the text’s arguments shows the value the text would hold for artists and writers interested in challenges AI presents to contemporary thought and action. Despite its broad success, however, I would argue the reader cannot help but detect a consistent struggle throughout the book to respond to the full incoherence of these fantasies that underpin discussions of AI in media, tech, and policy circles, without becoming at times incoherent itself. Given the mercurial status of AI—appearing as a name for specific technologies, the promise of future technologies, the desire for such technologies, and the very political, economic, and technological system (i.e., capitalism) that underpins the latter—the critic finds themselves in the position of the paranormal investigator—a sceptic, undoubtedly, but nevertheless alarmed by the sound of every snapping twig heard in the woods at night. Automatons freeing us from the drudgery of office work, silicon gods that will demand obedience, the cultural disasters ensuing from the invention of the Jacquard Loom, what are we talking about again? Despite its theoretical and argumentative sophistication at times, I 愛 AI wanders into the trap of reinforcing the very ambiguity AI’s boosters require to cover for their ongoing failures to meaningfully deliver improvements to culture, or even productivity. “AI knows not what it speaks”, writes Julia Thwaites towards the end of I愛 AI, “it is a language speaking itself in parody of human speech, a parody that may well become increasingly absurd” (172). How then to write critically about such absurdity without imputing too much dignity to the object of inquiry or without becoming absurd oneself?

I 愛 AI, edited by Sam Lieblich, is available at www.aestheticcalculations.com

Footnotes:

1. https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/post-mass-culture

2. Bullshit meant in Harry G. Frankfurt’s sense of bullshit as a statement, the truth value of which, the speaker or writer is entirely indifferent to.

3. https://fortune.com/2025/10/07/data-centers-gdp-growth-zero-first-half-2025-jason-furman-harvard-economist/

4. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/10/26/1082398/exclusive-ilya-sutskever-openais-chief-scientist-on-his-hopes-and-fears-for-the-future-of-ai/

5. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf

6. https://spikeartmagazine.com/articles/vulgarity-the-vulgar-image

7. For a recent example of the pervasiveness of this issue we can turn to OpenAi’s ban on creating short form videos of Dr Martin Luther King Jr on Sora: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5y0g79xevxo