Shannon Lyons and Lisa Liebetrau make an interesting duo; two artists whose critical practices often meditate on the roles of institutions and the experiences of those who come into contact with them. The artists are paired for the first time by curator Brent Harrison for The beautiful is useful—the fifteenth iteration of Tilt, Goolugatup Heathcote’s annual site-responsive exhibition. The pair have interrogated the building’s former use as the Heathcote Mental Reception Home, to thought-provoking ends.

Site-specificity/responsiveness has a particular appeal for galleries and arts organisations here in Western Australia, where a significant number inhabit heritage-listed buildings. These conditions have yielded both gaping yawns and immersive triumphs in equal measure. Particularly infectious is a kind of site-specific archive fever. The kind of site-specific archival work seen at a number of recent Tilt exhibitions find their antecedents in institutional critique, such as the works of Hans Haacke and Andrea Fraser, and decolonial practices—of which Brook Andrew is an exemplar par excellence.

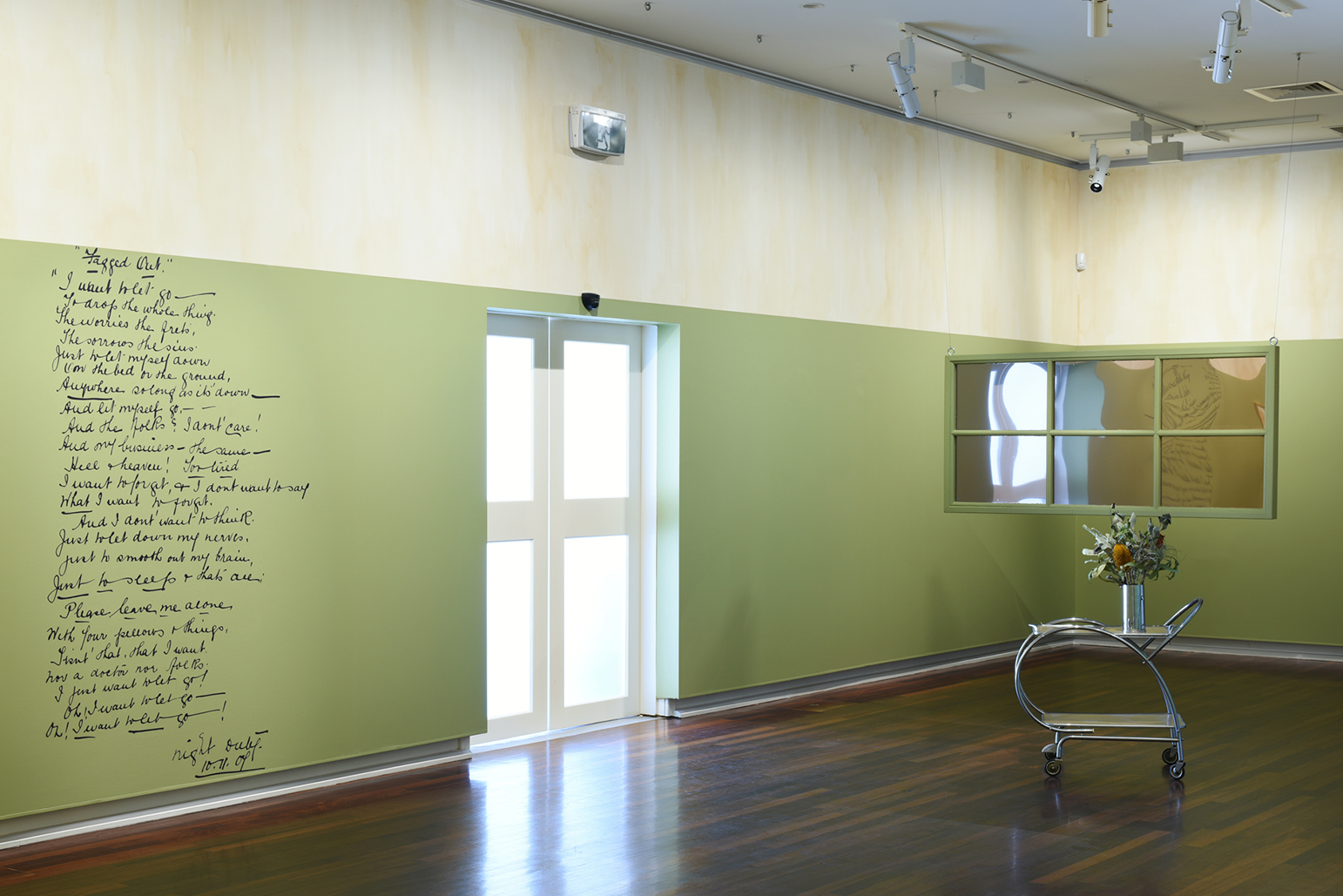

This array of critical practices are blended in The beautiful is useful. The walls of the gallery are painted a heritage green, with the top section stained in gentle translucent browns, painted with tea and coffee. The gallery is open, spacious, with work situated around the centre. Brent Harrison ensures that space is afforded to the work—a mix of paintings, text, assemblage and archival objects. Space is key. Content is dispersed, not dense. Whilst the archive is important, The beautiful is useful refrains from slipping into academic museology. As a result, Lyons and Liebetrau’s work blur concepts and mechanisms of “critique”: the artists evoke, conjure, suggest, and describe rather than solely explain, present, and inform.

Liebetrau plays the role of biographer-historian, mining various archives for items to recontextualise. Her work addresses specific and discreet stories, events and activities, as signified through her arrangements of archival objects and text. Liebetrau’s Six o’clock in the morning, twenty-five cups of tea and a judicious variety of flowers presents a dual function as both museological object and interpretive artwork. Her central work is a two-way mirror, floating within the gallery, which has been recreated in accordance with the original building plans—a reminder of the complex relationship between institutional care and panoptic observation. Here, Liebetrau acts as both informative historian as well as assembler of objects. Her work demands a particular type of looking from its audience; deriving meaning from and imparting meaning to their archival source material.

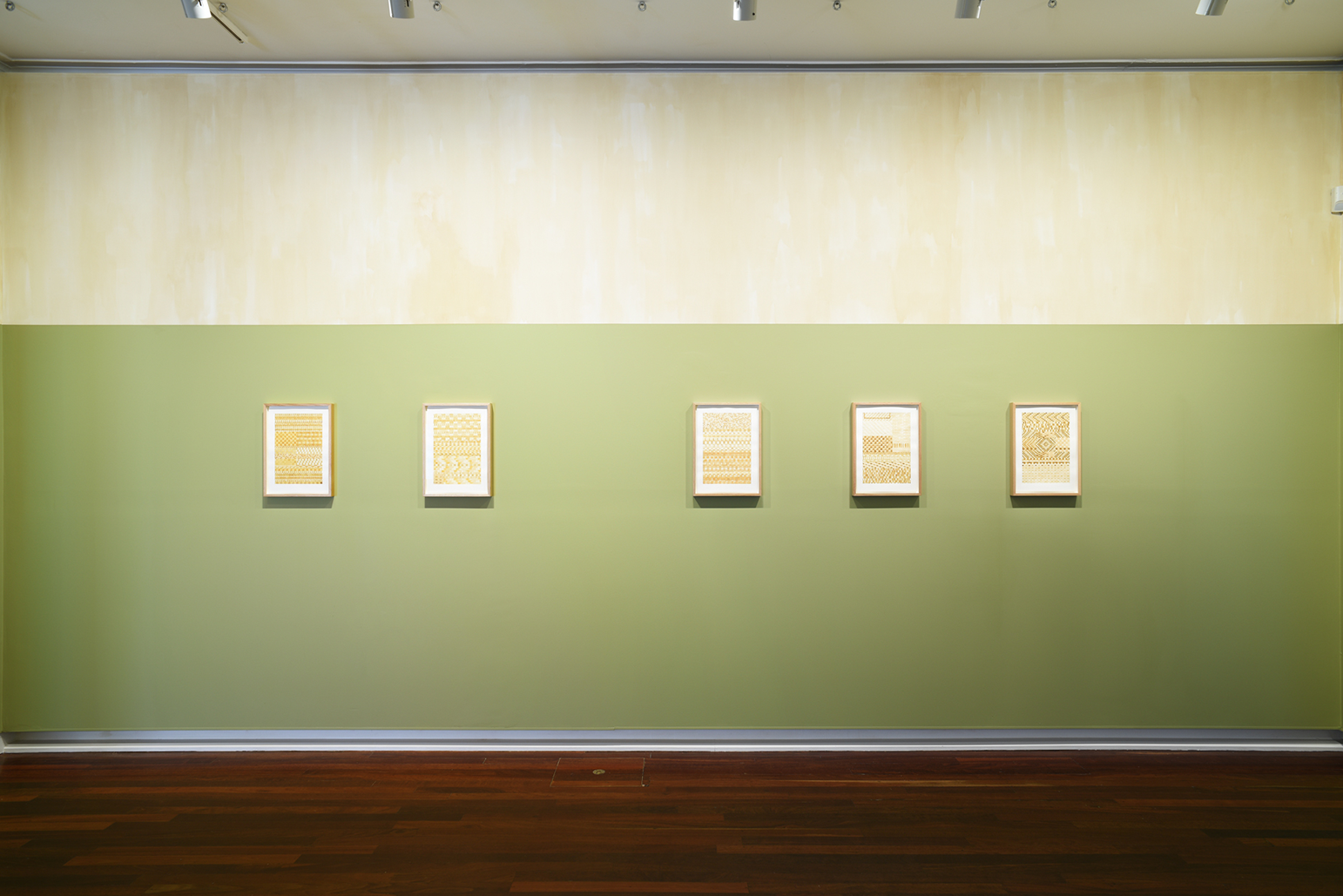

Acting as a counterpoint to Liebetrau’s archival investigations are Shannon Lyons’ tessellating tea and coffee-stained paintings (or drawings, perhaps). These works are visually appealing. The images are repetitive, yet never tiresome. Painterly washes stain the page in red-brick tones; oscillating grids of rigid linework. They are architectural: they meditate on the site and its lines, boundaries, and geometry. In this sense, the images are about the building’s structures, both physical as well as institutional. In Things went on I, light and dark stains outline architectural elements. Repeated viewings of these “floorplans” and “renders” had me wonder how life might have flowed through the old Mental Reception Home. The grids occasionally seem labyrinthine—connoting mazes, puzzles, and perhaps even crosswords. All of these connotations relate to repetitive pastimes and gentle activities that offer moments of respite and escapism for staff and patients alike. This might seem a long bow to draw, but it is certainly an entertaining possibility. This aspect of free association is part of the joy of Lyons’ images.

This thoughtfully interpretive dimension offers rewards upon repeated viewings. Mad Magladry and Francis Russell’s catalogue essay argues that Lyons’ paintings are a continuation of her ‘career-spanning attempt to draw attention to the structural forces that shape artistic production and interpretation’. Viewed with the building’s context in mind, the authors suggest the paintings ‘encourage us to think through the unique temporality of psychiatric ‘recovery’ and the confines of the hospital and gallery’. Another reading might argue that these paintings are, in fact, a departure from Lyons’ previous work, at least formally; that the very source of their interminable appeal is their ‘decorative and quietist’ nature. In their insightful text, Russell and Magladry conjure several of their own referential interpretations. So, perhaps it is this interpretive quality—the activation of the viewer’s curiosity and critical thinking—that sees these works as a continuation of Lyons’ broader practice.

Both Liebetrau and Lyons are artists who operate within similar conceptual paradigms to different, but complementary, aesthetic ends. Each have long been concerned with institutional critique. Neither are clumsy in their dealings with the subject matter offered by Goolagatup Heathcote. Brent Harrison intertwines their works visually, which fends off a tendency to compare or contrast the two artists’ responses to their shared subject. Instead, The beautiful is useful reads as a unified and engaging whole, a testament to Harrison’s curatorial vision.

Lisa Liebetrau and Shannon Lyons, The beautiful is useful, 4 Nov 2023 – 14 Jan 2024, Goolugatup Heathcote.

Images by Dan McCabe, artdoc, courtesy of Goolugatup Heathcote.

Site-specificity/responsiveness has a particular appeal for galleries and arts organisations here in Western Australia, where a significant number inhabit heritage-listed buildings. These conditions have yielded both gaping yawns and immersive triumphs in equal measure. Particularly infectious is a kind of site-specific archive fever. The kind of site-specific archival work seen at a number of recent Tilt exhibitions find their antecedents in institutional critique, such as the works of Hans Haacke and Andrea Fraser, and decolonial practices—of which Brook Andrew is an exemplar par excellence.

This array of critical practices are blended in The beautiful is useful. The walls of the gallery are painted a heritage green, with the top section stained in gentle translucent browns, painted with tea and coffee. The gallery is open, spacious, with work situated around the centre. Brent Harrison ensures that space is afforded to the work—a mix of paintings, text, assemblage and archival objects. Space is key. Content is dispersed, not dense. Whilst the archive is important, The beautiful is useful refrains from slipping into academic museology. As a result, Lyons and Liebetrau’s work blur concepts and mechanisms of “critique”: the artists evoke, conjure, suggest, and describe rather than solely explain, present, and inform.

Liebetrau plays the role of biographer-historian, mining various archives for items to recontextualise. Her work addresses specific and discreet stories, events and activities, as signified through her arrangements of archival objects and text. Liebetrau’s Six o’clock in the morning, twenty-five cups of tea and a judicious variety of flowers presents a dual function as both museological object and interpretive artwork. Her central work is a two-way mirror, floating within the gallery, which has been recreated in accordance with the original building plans—a reminder of the complex relationship between institutional care and panoptic observation. Here, Liebetrau acts as both informative historian as well as assembler of objects. Her work demands a particular type of looking from its audience; deriving meaning from and imparting meaning to their archival source material.

Acting as a counterpoint to Liebetrau’s archival investigations are Shannon Lyons’ tessellating tea and coffee-stained paintings (or drawings, perhaps). These works are visually appealing. The images are repetitive, yet never tiresome. Painterly washes stain the page in red-brick tones; oscillating grids of rigid linework. They are architectural: they meditate on the site and its lines, boundaries, and geometry. In this sense, the images are about the building’s structures, both physical as well as institutional. In Things went on I, light and dark stains outline architectural elements. Repeated viewings of these “floorplans” and “renders” had me wonder how life might have flowed through the old Mental Reception Home. The grids occasionally seem labyrinthine—connoting mazes, puzzles, and perhaps even crosswords. All of these connotations relate to repetitive pastimes and gentle activities that offer moments of respite and escapism for staff and patients alike. This might seem a long bow to draw, but it is certainly an entertaining possibility. This aspect of free association is part of the joy of Lyons’ images.

This thoughtfully interpretive dimension offers rewards upon repeated viewings. Mad Magladry and Francis Russell’s catalogue essay argues that Lyons’ paintings are a continuation of her ‘career-spanning attempt to draw attention to the structural forces that shape artistic production and interpretation’. Viewed with the building’s context in mind, the authors suggest the paintings ‘encourage us to think through the unique temporality of psychiatric ‘recovery’ and the confines of the hospital and gallery’. Another reading might argue that these paintings are, in fact, a departure from Lyons’ previous work, at least formally; that the very source of their interminable appeal is their ‘decorative and quietist’ nature. In their insightful text, Russell and Magladry conjure several of their own referential interpretations. So, perhaps it is this interpretive quality—the activation of the viewer’s curiosity and critical thinking—that sees these works as a continuation of Lyons’ broader practice.

Both Liebetrau and Lyons are artists who operate within similar conceptual paradigms to different, but complementary, aesthetic ends. Each have long been concerned with institutional critique. Neither are clumsy in their dealings with the subject matter offered by Goolagatup Heathcote. Brent Harrison intertwines their works visually, which fends off a tendency to compare or contrast the two artists’ responses to their shared subject. Instead, The beautiful is useful reads as a unified and engaging whole, a testament to Harrison’s curatorial vision.

Lisa Liebetrau and Shannon Lyons, The beautiful is useful, 4 Nov 2023 – 14 Jan 2024, Goolugatup Heathcote.

Images by Dan McCabe, artdoc, courtesy of Goolugatup Heathcote.