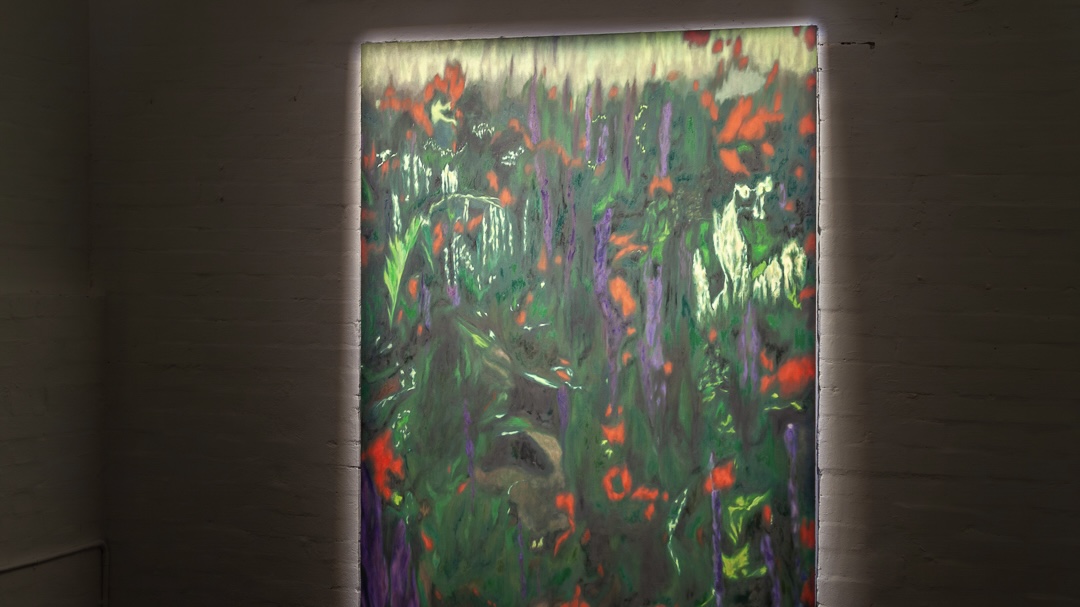

All painters, perhaps, in their secret heart, wish for a return to the medieval. To the resacralization of art and the reconstitution of its religious affect—a return to the magic of images, to the image as magic. In Jacob Kotzee’s flowerfield, Current Gallery’s reclamation of the Old Naval Store’s junkspace brick storage shed was remade into a shrine for a single painting ensconced like an altarpiece in the gallery’s north wall. A non-specific painting of a “non-specific field of flowers”[1]; just abstracted enough to avoid falling into accusations of kitsch that might accompany a figurative painting of actual flowers.

Kotzee’s methodology usually involves the selection of photographs or film stills as painting reference, interrogating the construction of cultural and political mythologies through imagery, though here this process is omitted from any discursive statement (or lack thereof) about the work. I assume the painting was painted from reference to some photographic image, and so situated somewhat in the tradition (and aesthetic) of Monet’s water lilies, which he painted from his garden pond, an artificial landscape created to serve as a reference material for painting; a mediated image of an already mediated image of a vague landscape. Or perhaps more in the vein of Rothko’s paintings for the Rothko Chapel in Texas; the work is emptied of content to be filled with affect.

Through darkness and light, Current Gallery is made into a makeshift shrine. The painting is made-to-measure for its north wall recess, like a holy relic illumined in a darkened sepulcher; a cave painting in the rarefied crawlspaces of Lascaux. There is a conscious striving here to achieve a heightened experience of presence, to reconstitute the cult-value of the art-object through isolation and illumination. Unfortunately, the directness of the lighting does not always jibe with the materiality of the paint. In the sunken-in areas, the hard glare washes it out, rendering it flat and lifeless, obscuring detail. I’m reminded of Frank Auerbach’s Looking Towards Mornington Crescent Station, Night currently on display at AGWA; a wonderfully expressive work whose material impact up close is let down by insensitive lighting. Or Melissa Clement’s recent exhibition Flight of the Battery Hens at PS Artspace, in which a penchant for glossy varnish and spotlights obliterates the proficiently rendered faces in her portraits when scrutinised from the wrong position. Such installs are always predicated on an idealised subject, one standing in removed, passive contemplation of the work of art. Stand on your mark and look, no moving around. I’ll refrain from too much judgement of the painting itself, because the painting itself is beside the point, which is the striving for the auratic possibility of the artwork achieved through its staging.

Walter Benjamin locates the aura of an artwork in “its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” which “withers” with its reproduction.[2] But there is no longer any question of the reproduction of the artwork, which always now exists in a multiplicity of states, both physical and digital. Exhibitions now begin before their actual opening, existing not as a discrete experience, but a flow of images that precede and proceed it.[3] Kotzee has resisted the dispersed experience of art in the age of social media by carefully curating the lead up to the exhibition, consciously avoiding the pre-reproduction of the work. The painting was revealed/veiled through cropped sections teased on instagram stories, disappearing after 24 hours, careful not to hint at the form of the exhibition or even the quantity of works. Will Ek-Uvelius, the poster designer, mentions his discussions with the artist being “centred around maintaining an element of surprise when visitors experience the work in person at the gallery”. [4] Aura is diminished through reproduction; the aura of the work is maintained by denying its reproduction before the fact. The cult-value of the art-object rests in its being hidden away, revealed only in its proper time and place; revealed as revelation.

Benjamin elucidates the aura of artworks with reference to the aura of natural things as “the unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be”.[5] Distance and proximity is inherent in Kotzee’s painting; the close up image of a flower field is ambiguated through the abstraction of paint; a fuzzy rendering, barely legible as what it is without the titular hint. There is a unique sensation of being within this field but also removed from it, a vacillation which draws us in through the desire to resolve this ambiguity through proximal inspection, to be intimate with the materiality of the paint. But this desire for intimacy is rebuffed by the hard glare of the light up close, by the resistance of the painting to resolve into specificity, and we are sent back to our proper place.[6] The auratic always insists on distance, on the separation of the subject from the object, on which aura depends.

In the week after the close of flowerfield the usual flow of documentation has been uploaded to instagram. Shots of silhouetted viewers in contemplation on Current Gallery’s feed, and finally documentation of the work in isolation on Kotzee’s instagram and website. I have to profess myself disappointed with this regression to the usual formalities of the post-exhibition. If the exhibition is not documented, did it even happen? If it does not at least allow the possibility of its historicisation, can it ever be important? But what remains of the artwork after its acquiescence to the discursive field, and what is lost by not allowing it to remain in its time and space?

Footnotes:

1. https://current.gallery/025-FLOWERFIELD

2. Walter Benjamin. 1935. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

3. fakewhale. April 2, 2025. “Beyond the Real: Art in the Age of Perpetual Reproduction”https://log.fakewhale.xyz/beyond-the-real-art-in-the-age-of-perpetual-reproduction/

4. https://www.instagram.com/p/DHkcl6CJxE1/?img_index=1

5. Walter Benjamin. 1935. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

6. For a discussion of the effect of light as both revealing and concealing/obscuring see Barbara Bolt’s “Shedding Light for the Matter”.

Image credits: Artwork by Jacob Kotzee. Photographs by Scott Burton.

Kotzee’s methodology usually involves the selection of photographs or film stills as painting reference, interrogating the construction of cultural and political mythologies through imagery, though here this process is omitted from any discursive statement (or lack thereof) about the work. I assume the painting was painted from reference to some photographic image, and so situated somewhat in the tradition (and aesthetic) of Monet’s water lilies, which he painted from his garden pond, an artificial landscape created to serve as a reference material for painting; a mediated image of an already mediated image of a vague landscape. Or perhaps more in the vein of Rothko’s paintings for the Rothko Chapel in Texas; the work is emptied of content to be filled with affect.

Through darkness and light, Current Gallery is made into a makeshift shrine. The painting is made-to-measure for its north wall recess, like a holy relic illumined in a darkened sepulcher; a cave painting in the rarefied crawlspaces of Lascaux. There is a conscious striving here to achieve a heightened experience of presence, to reconstitute the cult-value of the art-object through isolation and illumination. Unfortunately, the directness of the lighting does not always jibe with the materiality of the paint. In the sunken-in areas, the hard glare washes it out, rendering it flat and lifeless, obscuring detail. I’m reminded of Frank Auerbach’s Looking Towards Mornington Crescent Station, Night currently on display at AGWA; a wonderfully expressive work whose material impact up close is let down by insensitive lighting. Or Melissa Clement’s recent exhibition Flight of the Battery Hens at PS Artspace, in which a penchant for glossy varnish and spotlights obliterates the proficiently rendered faces in her portraits when scrutinised from the wrong position. Such installs are always predicated on an idealised subject, one standing in removed, passive contemplation of the work of art. Stand on your mark and look, no moving around. I’ll refrain from too much judgement of the painting itself, because the painting itself is beside the point, which is the striving for the auratic possibility of the artwork achieved through its staging.

Walter Benjamin locates the aura of an artwork in “its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” which “withers” with its reproduction.[2] But there is no longer any question of the reproduction of the artwork, which always now exists in a multiplicity of states, both physical and digital. Exhibitions now begin before their actual opening, existing not as a discrete experience, but a flow of images that precede and proceed it.[3] Kotzee has resisted the dispersed experience of art in the age of social media by carefully curating the lead up to the exhibition, consciously avoiding the pre-reproduction of the work. The painting was revealed/veiled through cropped sections teased on instagram stories, disappearing after 24 hours, careful not to hint at the form of the exhibition or even the quantity of works. Will Ek-Uvelius, the poster designer, mentions his discussions with the artist being “centred around maintaining an element of surprise when visitors experience the work in person at the gallery”. [4] Aura is diminished through reproduction; the aura of the work is maintained by denying its reproduction before the fact. The cult-value of the art-object rests in its being hidden away, revealed only in its proper time and place; revealed as revelation.

Benjamin elucidates the aura of artworks with reference to the aura of natural things as “the unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be”.[5] Distance and proximity is inherent in Kotzee’s painting; the close up image of a flower field is ambiguated through the abstraction of paint; a fuzzy rendering, barely legible as what it is without the titular hint. There is a unique sensation of being within this field but also removed from it, a vacillation which draws us in through the desire to resolve this ambiguity through proximal inspection, to be intimate with the materiality of the paint. But this desire for intimacy is rebuffed by the hard glare of the light up close, by the resistance of the painting to resolve into specificity, and we are sent back to our proper place.[6] The auratic always insists on distance, on the separation of the subject from the object, on which aura depends.

In the week after the close of flowerfield the usual flow of documentation has been uploaded to instagram. Shots of silhouetted viewers in contemplation on Current Gallery’s feed, and finally documentation of the work in isolation on Kotzee’s instagram and website. I have to profess myself disappointed with this regression to the usual formalities of the post-exhibition. If the exhibition is not documented, did it even happen? If it does not at least allow the possibility of its historicisation, can it ever be important? But what remains of the artwork after its acquiescence to the discursive field, and what is lost by not allowing it to remain in its time and space?

Footnotes:

1. https://current.gallery/025-FLOWERFIELD

2. Walter Benjamin. 1935. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

3. fakewhale. April 2, 2025. “Beyond the Real: Art in the Age of Perpetual Reproduction”https://log.fakewhale.xyz/beyond-the-real-art-in-the-age-of-perpetual-reproduction/

4. https://www.instagram.com/p/DHkcl6CJxE1/?img_index=1

5. Walter Benjamin. 1935. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

6. For a discussion of the effect of light as both revealing and concealing/obscuring see Barbara Bolt’s “Shedding Light for the Matter”.

Image credits: Artwork by Jacob Kotzee. Photographs by Scott Burton.