‘The

history that's not told is often the most interesting’: A conversation with Jo Darbyshire

Saturday, 11 January 2025

For as long as I’ve

been an arts worker, and long before meeting her, Jo Darbyshire has been on the

periphery of my awareness. This comes as no surprise: she has curated and

exhibited in Perth/Boorloo (and further afield) for decades.

When I learnt that Jo had been invited to curate an exhibition at Fremantle Arts Centre, with the curatorial premise being local protests, my interest was piqued immediately. I was skeptical about the potency of such an exhibition positioned within a local government context. I reflected on this as someone who has worked in arts roles at various local governments for many years, and participated in both the successes and shortcomings of this bureaucracy.

To spend this time with Jo has been an education in how to sustain a vigorous practice. She is both gentle and forthright. She actively welcomes others’ opinions, but never minces her words. This balance in her personality is, I feel, one of the reasons she is a well-regarded, prolific artist. She is driven to produce artistic outcomes that speak unwaveringly to this time, and its politics: a drive that is, ultimately, from a place of genuine care for others.

Desperate Measures is a showcase of objects from the City of Fremantle’s Civic and Art Collections, curated by Jo Darbyshire. The exhibition draws its name from the Fremantle-based theatre group, mostly active between 1977–1985. The Desperate Measures troupe wrote and performed political street theatre, led protests and demonstrations in Fremantle, and ran workshops with incarcerated people in prisons.

Desperate Measures works well in the context of Fremantle Arts Centre because Jo has designed the exhibition so as to highlight the aligned interest between the values of the Desperate Measures troupe, and local government, never compromising on the important aspects of protests by the troupe. At its best, local government celebrates and supports the community—for all its potency and, at times, dowdiness. Jo recognises this spirit, and highlights the way artists rallied (and continue to rally) with the broader community to generate change—manifest in City of Fremantle Council minutes, an object which features in Desperate Measures.

The artist I have subsequently come to know—in equal parts straight-talking and compassionate—is the one you will encounter below.

Stirling Kain: Tell me about your intention and your background as a curator, and as a researcher, and as an activist. I don't know if you consider yourself an activist, I haven't talked to you about that yet.

Jo Darbyshire: I prefer to call myself an artist-curator, because I think artists can be activists by their very nature. We're taught in art school to question things, to come up with alternatives, and to not be stopped. That's probably one of the best things about being an artist—you learn to go around obstacles and to think more laterally about problems. I think it's quite powerful to be an artist-curator.

SK: So for you, maybe 'curator' doesn't have that inherent sense of activism, but the word 'artist' does, and you include the sense of activism when you call yourself an artist-curator?

JD: In my mind, I like to think of the artist as being an activist. I mean, many artists are not, but putting 'artist' and 'curator' together, that is, for me, one of the great joys of life—when I'm allowed to curate an exhibition and I can use some of the skills that I have learned as an artist.

SK: I want to return to what we talked about a few weeks ago, when we were at the Fremantle Arts Centre, and one of the first things we talked about—how does a protest exhibition sit in a local government gallery context? Initially, I was thinking, ‘does the exhibition become less radical in that local government context, or does the gallery become more politically radical?’ And now I’ve seen your exhibition, I've been thinking that it really depends on the intent, and who's involved.

JD: It really depends on whether it's supported all the way up the line, and if you've got a manager or a person that's really supportive of the message being given, that is unimpeded, not sanitized. As soon as you sanitize anything, you kill it. Society is not sanitized, but people love to sanitize in museums, and they love to sanitize things in local government. City of Fremantle has been fantastic, because they trusted me—there's been no censorship and they're happy for this to be seen as a historical exhibition. But this exhibition is not trying to be political or controversial. I never try to be controversial. I just think history is controversial. It's how you interpret it, and when—the context.

I was asked to work with the curator Andre Lipscombe, and with the City of Fremantle Art and Civic Collections. The curators in the past would not have collected work, thinking that one day these works would be used in an exhibition about activism in Fremantle. So, they didn't really buy those works or acquire them for that purpose. But I think if you allow outside curators to come in, we can make meaning out of what is in those collections.

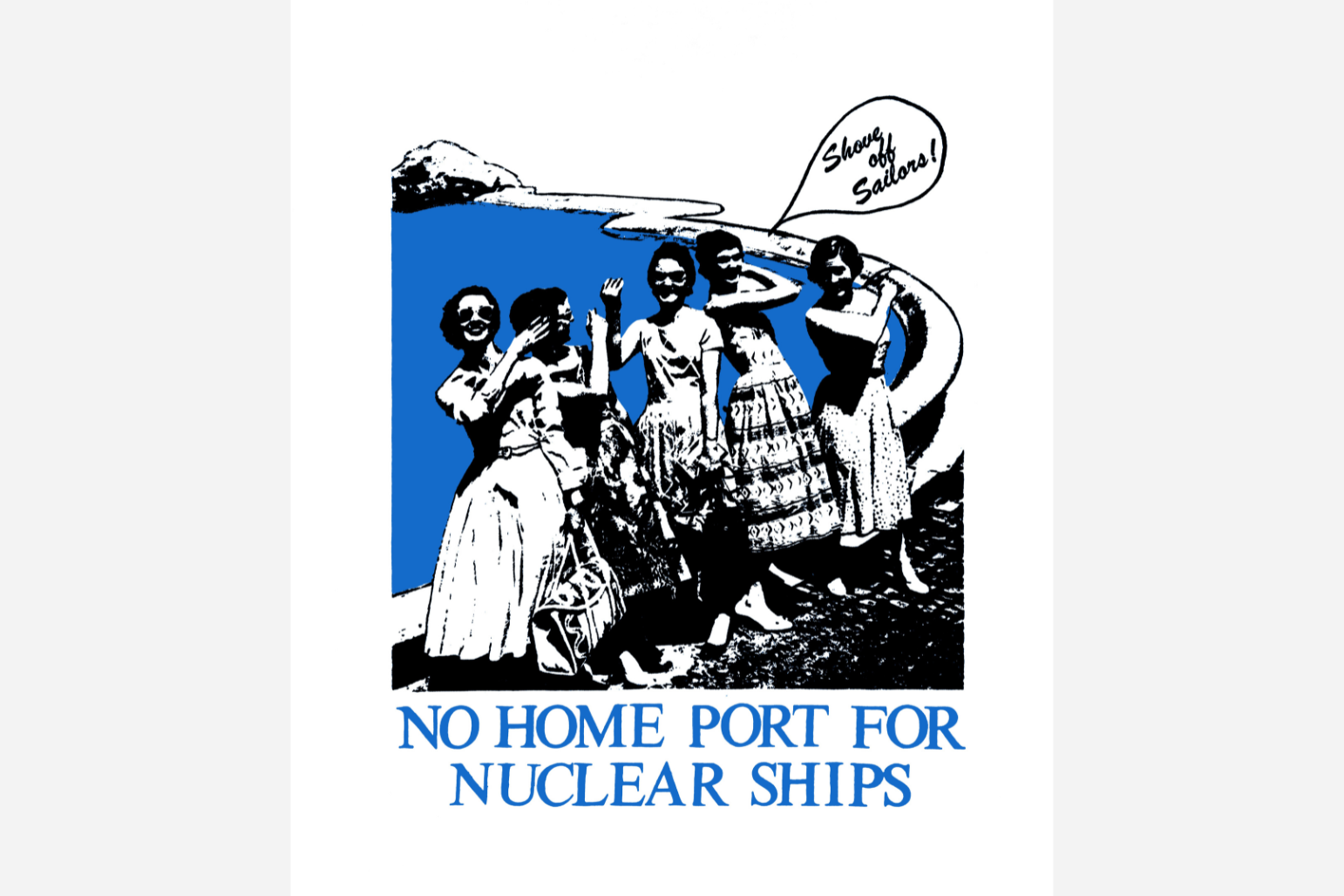

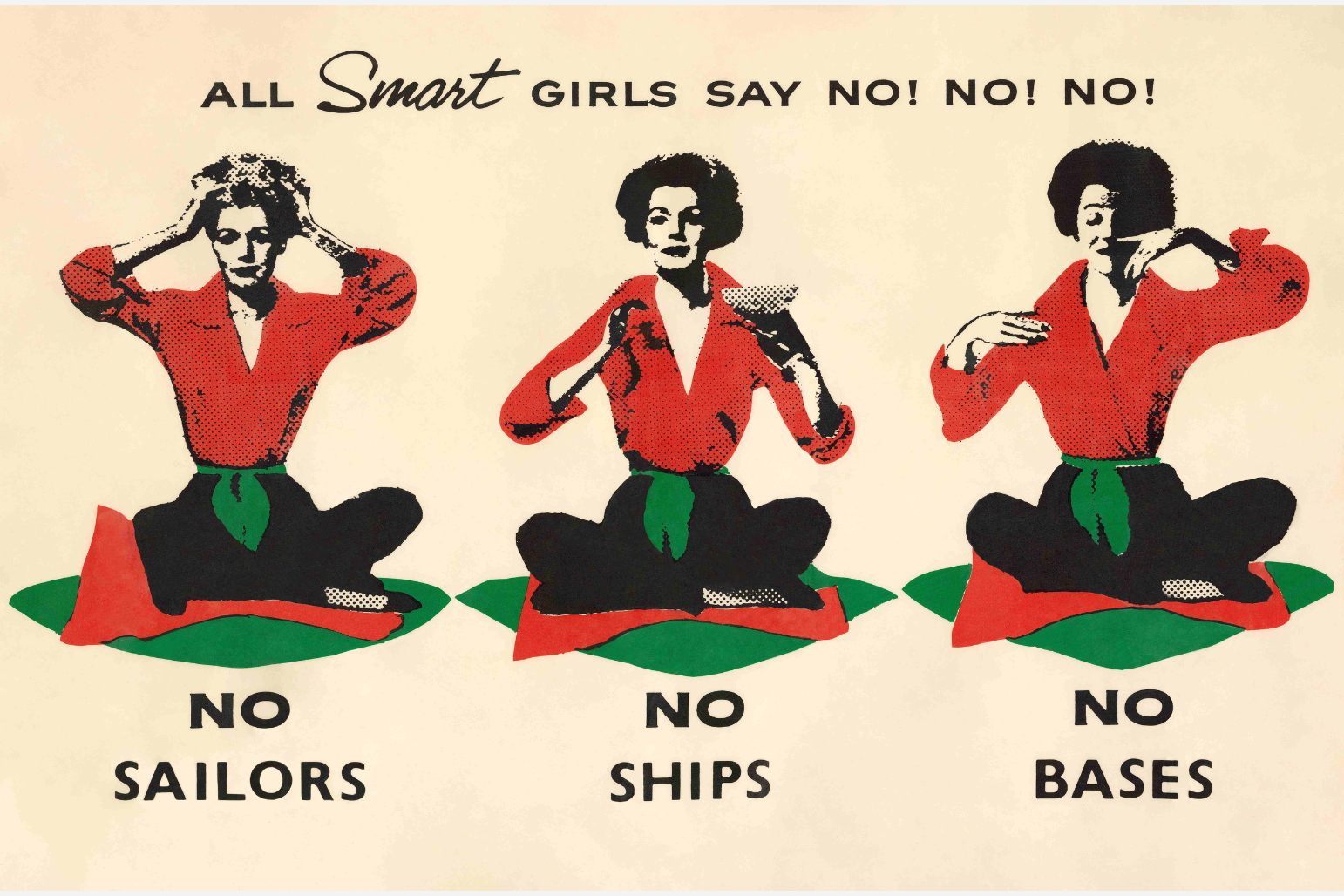

In this exhibition, we've also included a ceremonial plaque from one of the US nuclear warships that came in the ‘80s—and a hell of a lot of them did come to Perth and Fremantle. Most councils have these plaques from these US ships. And no one usually knows what to do with them. They're stuck in a cupboard somewhere, and then they're de-politicized—they're just a gift from that ship. So, to put them in a context—you've got the anti-nuclear protesters, showing their banners on the ship, which we've got photographs of—and to juxtapose the plaque next to it—is to show the connection between local government and the protests. They were welcomed by the council and the mayor, and then at the same time, they weren't welcomed by the local community. And quietly, I'm trying to make those connections visible to people and to say, ‘well, we're in exactly the same situation right now.’

SK: I've been thinking about a museological framework for protest exhibitions and using collections. I don't know if you saw the exhibition 1948: Palestine in Pictures, at Pakenham Street Art Space, with Cool Change Contemporary?

JD: Yeah, it was fantastic.

SK: It was really wonderful. And I felt it adopted a museological framework like Desperate Measures. And I wonder if that was informed by the fact that the people depicted, the Palestinian community, many of them had left their ancestral homes. The exhibition reflects what they were able to bring with them when they immigrated—small, flat objects like photographs. Reflecting on that exhibition, alongside Desperate Measures—what is it about using that museological framework and collections, within the context of a protest exhibition, that works so well? There's something particularly that you are drawn to, and I think that framework works really well in other protests exhibitions as well.

JD: What I liked about that exhibition—they used a whole range of objects and photos. They had vintage and contemporary photos, and vintage and contemporary objects. They put it together in a way that was more Installation than didactic interpretation. They also had sparse and beautifully curated text. They had quotes and video, and they also had a little bit of writing to put the exhibition in context. I love exhibitions like that—what I would call ‘encyclopedic’—using all the things that are available, to really draw people into the story.

You always need objects, I think, or really great photos—and this is where the visual arts come in—you're creating an opportunity for people to become bodily immersed in what they call a 'history exhibition.' Because history is often presented as didactic and dull—and sometimes it really can be. You can just kill history by how it's put together. But that exhibition, and I'm hoping the exhibitions that I do, try to make people bodily connected to what they're reading and what they're seeing. So, using text in a kind of visual way.

Sometimes you can't get to do that, because graphic designers tend to have a format. You know, they have the wall text, so they have the little label text that goes next to the object. I like to play around with those. I think that often the information that's in the little wall text is actually really vibrant and interesting.

SK: You definitely played with that in Desperate Measures, with the text being so physically large. And I also happened to see those conversations you had with the graphic designer right at the end. You were saying that the text in the panels was the incorrect size. And, on this occasion, that wasn't the graphic designer's fault, but that was a really important part for you.

JD: It is. I like to design exhibitions. I really have to have a visual idea in my head about the connection between that photo and the text next to it. You know, there are exhibitions where you just have wall label after wall label, and it's all the same, and it's all designed within a format. I prefer to prioritize the important text.

Cool Change Contemporary did this as well, with 1948: Palestine in Pictures. The bigger text: people are going to read that first. So, you make that the priority text. And then if people think 'I'm really interested in this little story', then they go into it further, and they might get the subtext, or they might read another little story around that, or they might understand a joke at the end.

Some people just walk into a history exhibition and they just want to look at the photos. So to have really interesting photos is fantastic. And in this show, I was really careful not to have too many photos, but to choose photos that were going to be super interesting for people, to draw people in and think, ‘oh, am I in the photo, or do I know someone in the photo?’ People love to interact with photographs.

SK: Something that I think about as an arts worker is that people often first go to the text, the explanation, and not the image. But in a history exhibition, you're saying that's reversed, and maybe it's because people think that they'll see themselves or someone they know, that they have a really personal connection to, in those images.

JD: I think people resist a lot of text. But if you are trying to get a story across you have to have facts, and you have to present them in a way that is not too didactic, but actually truthful—like if someone speaks in their own voice. That's also important.

SK: It's interesting that you say ‘truthful’. I think honesty is real when it includes people's voice. The way they speak, but then, their feelings as well.

JD: I agree with you. When you have people speaking, that's their truth. You can also have negative voices, and they are good to have in an exhibition about history, because they show what people were fighting against. So for instance, that little newspaper article in Desperate Measures, which headlines the then-Premier of Western Australia calling activists ‘evil’. That was just gold, because you could see the conservative forces that people were acting against. It's also quite humorous, because politicians often shoot themselves in the foot. You're just presenting the truth of what they said.

SK: And I'm thinking of that one quote from the Desperate Measures exhibition, one person talking about their experiences seeing Lesbian women on stage and performing.

JD: That was really fantastic. One of the Desperate Measures performers wrote to me—she said, ‘we weren't overtly into Queer stuff at that time, but we were exploring Feminism. And then, as part of that, we started to have Lesbian relationships.’ And she actually said, ‘when I was on tour to Adelaide, I became a Lesbian!’

SK: That's right, yeah! That's it.

JD: And so I wrote back to her and I said, ‘can I use that quote?’ Because it saves me having to be didactic. And saves me putting something into the text saying, 'oh, and Desperate Measures had lots of Lesbians involved', you know? It says a lot more than me just saying the bare information.

SK: How do you see protest happening today, as compared to Desperate Measures? What is the same, what’s different? For better or worse.

JD: I think there are definitely things happening, and in a different way to what Desperate Measures did. Hopefully with just as much fun, and also that commitment to it. That's going to be the crux in the future—how we work together as activists.

SK: You're absolutely right. I'm thinking that protest now looks very different to what Desperate Measures were doing—specifically, the artists I've seen protesting recently at fundraisers, they're performing in venues like the Buffalo Club.

JD: The aim of Desperate Measures was to do things publicly. I think everyone's gone a bit underground or online. There's certainly been consequences recently for artists that have even liked posts online. Big consequences for West Australian artists.

SK: I've been meaning to speak to you about that. I know recently in Sydney there was a climate protest to stop traffic on the Sydney Harbor Bridge, two of the protesters were charged.[1] Their jail sentences were successfully appealed, but one of the protesters was convicted of related charges. I'm interested in what you think—does that kind of response from the state influence how people protest?

JD: Absolutely. The protests that I have been arrested for—which were Roxby Downs uranium mine, Pine Gap in 1983, and, more recently, Roe 8—I would only get arrested when I knew that there was a big group of people getting arrested at the same time, and that we had pro bono lawyers ready to look after us, and bail us out. So I would not encourage anyone to go and do their own project and get arrested by themselves. Always do it with a group, and always have a lawyer.

All of these anti-nuclear [Project Iceberg] protesters that were arrested on US war ships in the ‘80s—they had lawyers, and those lawyers are still around. They organized themselves well, to keep things safe and to keep it non-violent. They all did ‘non-violent action training’, which was a weekend workshop where you learnt how to resist the police, but not to resist arrest.

SK: That reminds me of a conversation I had recently—someone commented that protesters and artists often have a really strong understanding of bureaucracy, because they have to navigate the bureaucracy.

JD: I think artists should break rules, but only when they know what the rules are. And only when it's better to break the rule than to keep it. I believe that's the same for activism.

SK: That's such a powerful statement. And you, personally, navigate bureaucracy by working within museum and art collections. That’s part of your protest and activism.

JD: I think it's great to invite artists to do exhibitions in museums. I mean, we just enliven them.

SK: Yeah, absolutely. We have spent time talking about that before—how archives can be living and breathing, but people have to imbue them with breath. They have to be used.

JD: That's beautiful. And a lot of people are afraid to let those archives be used in that way. Artists are not often welcomed into museums as curators. We have to claim that space. But once we are given the opportunity—we contribute to New Museology discourses, and we've really changed things in museums. Fred Wilsons' Mining the Museum exhibition, which showed slave shackles within a very traditional museum—he really changed the whole discourse. From there, other artists have worked with museums and really changed things as well. It's great to make history live. To make people realise: one, they're part of it, just in their ordinary, everyday lives. And two, the history that's not told is often the most interesting. When I did The Gay Museum…

SK: I'm so excited to talk about The Gay Museum! I love The Gay Museum!

JD: Did you see it?

SK: No, it was before my time, but I read your essay about it, and I loved it.[2]

JD: I knew that I wanted to go in and make an exhibition about gay and lesbian history in WA, but I couldn't until 2002, when the law changed.[3] Before that, institutions couldn't 'promote homosexuality'. As soon as we got that law reform, I went in and asked them, 'I want to do this'. Luckily, the Director of the Museum at the time, Dr. Gary Morgan, had just worked with Brooke Andrews at the Sydney Museum—so he said, 'okay'. It was quite a conservative Museum and there was a lot of resistance from the history department, from lots of people.

I had to be an enrolled master’s student to make The Gay Museum. They wouldn't let me just come in as an artist. But I had a fantastic supervisor called Mat Trinca, and he really helped me. And I got a lot of support from staff who were just waiting for someone to do something like this in the Museum. I wanted to bring something from every single department, to say: being gay, or being Lesbian, or Homosexual is not something that is outside of anything. We are part of everything.

For instance, they wanted me to bring in panels and stick them on the wall. And I said, no, no—I want to paint the walls black, and I want to have text panels really embedded in the space visually, so that we actually are part of the museum. It was a big project, but it was amazing. I worked with the community, and I worked trying to find empirical evidence. That was very difficult, because there was hardly anything—there was nothing collected in the Museum.

When I first went to the history department, I said that I wanted to physically look at all the collections. They said, no, no—you have to put search words into the catalogue. So, of course, what came up was one AIDS t-shirt, from South Australia. That was literally it.

SK: Ha!

JD: Then I found this crab—it was called a Shame-faced crab. And I thought, 'this is perfect.' So, I was able to talk about how museums think that they are objective, and yet they often name things with subjective meaning. So, I used that crab to talk about how Homosexuals were conditioned to feel shame, and how that affected their lives.

I found an electric shock machine in the Museum—which was in a medical section. It would have been kept for a medical display. But I put it near the Shame-faced crab, and talked about how gay men went through this terrible ‘conversion’ treatment. Right up to about 1978, they would be electrocuted with this machine to try and make them not gay; shocking them when they were shown pictures of naked men. That happened right here in WA, at Heathcote Hospital.[4]

And in that same exhibition, one of my art students at Edith Cowan University showed me his collection of ‘used soaps’, and I begged to use them. I displayed them next to the electric shock machine. All of these used soaps were not only beautiful as an installation, but they talked about trying to clean that ‘stain’ of Homosexuality, the shame that people felt in those days. So, taking things out of their normal context and using them metaphorically or poetically, or juxtaposing them with text that gave them a different context pertinent to gay and lesbian people, made a big difference.

SK: You would never have found the electric shock machine just by searching 'gay' and 'lesbian', or found it at all, unless you were looking for an electric shock machine. We've been talking about archives, and it's really important to think about how people might use them, in order to know how to categorise the objects. You have to future-craft in that way. And there are methodologies to researching and archiving that people can be educated in—but these things might change over time.

JD: Being able to have search words in an archive is important. You're right. However, I found the electric shock machine by looking physically through the collection. I would work for hours, searching through, and not find anything. And then suddenly you would come across something. And think, ‘wow, that's perfect.’ Like the Shame-faced crab was just perfect.

SK: Do you find that when you're making artwork as well, for example, paintings?

JD: Yeah.

SK: That's what I find in my practice, too. It can be a lot of nothing, nothing, nothing, and then you find something.

JD: Yeah. And that moment of joy, where it just comes.

SK: The curatorial research looks similar in the way it unfolds, to the making process of art.

JD: Putting yourself there, doing all the hard work to allow something to come—I think that's what painting is. And I think that's what curating an exhibition like this is. I did a lot of work contacting people about Desperate Measures and then asking them to send me stories.

A good example—Kati Thamo told me how she and Mandy Browne had ridden bikes up to Perth and did some graffiti on a public wall, which said, 'There once was a land full of laughing trees'. That graffiti stayed there for years, and someone made artwork about it, but Kati didn't know who. I searched online and found that we had a beautiful image in the State Art Gallery, and in the National Gallery as well. Screenprints had been made by Peter Clemesha, using a photograph he'd taken of the graffiti. That was one of those moments where I just thought, 'oh my God'. Peter Clemesha lives in Fremantle, and he never knew who made the graffiti. Kati and Mandy knew someone had made art about it, but they never saw it again. So, to bring them together was one of those great serendipitous stories about that time.

SK: It's interesting how these images relating to, and objects used for, protests are then acquired by institutions.

JD: They're starting to be. Initially, for Roe 8, they didn't want anything, but we collected everything ourselves, and we did work with the community. We made a database. There was a lot of art: posters, t-shirts, tea towels, banners. Even concrete Lock-on Barrels. We managed to save two of those out of the Roe 8 bush. One of those has gone to the WA Museum, and one has gone to the National Museum. I was pretty pleased to see the WA Museum collecting Disrupt Burrup stuff.

SK: I don't know how to feel about that yet.

JD: Well, they don't know how to exhibit them yet!

SK: I'm thinking about the Perspex that Joana Partyka spray-painted at the AGWA Disrupt Burrup Hub action from 2023. It was recently acquired by the WA Museum. She’s facing charges for her protest—but another state-funded institution only five-hundred meters away can acquire the object for its collection?

JD: But as Alec Coles [Director, WA Museum] said—the Museum's job is to collect both sides of an issue. In the past, they haven't. There are a lot of things that have never been collected, like women's history, and multicultural history. These were colonial institutions, and they looked at everything through that empirical lens. It's only since New Museology came on the scene—since the ‘80s and ‘90s—when people questioned the role of museums, that things have changed.

I think it's great that the Museum is collecting that protest material. It has to question itself as well. That's what happened in The Gay Museum. The museum was asked to question its own collecting practices, and its own curatorial practices. I think that was quite challenging for them, but they did. It really depends a lot on who's working in those places as well, as to what gets collected.

Desperate Measures: Art, Politics and Performance in Freo 1977 –1985, Fremanlte Arts Centre, 9 November 2024 – 27 January 2025.

—

Jo Darbyshire was born in 1961 in Perth, Western Australia. She studied Fine Arts at Curtin University in 1981, a Postgraduate Diploma at Canberra School of Art in 1991 and a Master of Creative Arts in Cultural Heritage at Curtin University of Technology in 2004.

Stirling Kain is an arts worker and artist in Perth (Boorloo). As an arts worker, she produces art festivals and events. Her photography practice involves film and darkroom techniques. Kain graduated with a Bachelor of Art (History of Art maj., History min.) from the University of Western Australia in 2020.

Footnotes:

1. See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/mar/15/climate-activist-deanna-violet-cocos-15-month-jail-sentence-overturned-on-appeal

2. See https://www.jodarbyshire.com/uploads/text-files/gay_museum_catalogue.pdf

3. See https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/prod/filestore.nsf/FileURL/mrdoc_7865.pdf/$FILE/Law%20Reform%20(Decriminalization%20of%20Sodomy)%20Act%201989%20-%20%5B00-00-00%5D.pdf?OpenElement

4. Tony Thomas, ‘Homosexuals and Perth’, The Critic, University of Western Australia, vol.8, no.10, 1968, p.94.

Images courtesy of the Fremantle Arts Centre.

When I learnt that Jo had been invited to curate an exhibition at Fremantle Arts Centre, with the curatorial premise being local protests, my interest was piqued immediately. I was skeptical about the potency of such an exhibition positioned within a local government context. I reflected on this as someone who has worked in arts roles at various local governments for many years, and participated in both the successes and shortcomings of this bureaucracy.

To spend this time with Jo has been an education in how to sustain a vigorous practice. She is both gentle and forthright. She actively welcomes others’ opinions, but never minces her words. This balance in her personality is, I feel, one of the reasons she is a well-regarded, prolific artist. She is driven to produce artistic outcomes that speak unwaveringly to this time, and its politics: a drive that is, ultimately, from a place of genuine care for others.

Desperate Measures is a showcase of objects from the City of Fremantle’s Civic and Art Collections, curated by Jo Darbyshire. The exhibition draws its name from the Fremantle-based theatre group, mostly active between 1977–1985. The Desperate Measures troupe wrote and performed political street theatre, led protests and demonstrations in Fremantle, and ran workshops with incarcerated people in prisons.

Desperate Measures works well in the context of Fremantle Arts Centre because Jo has designed the exhibition so as to highlight the aligned interest between the values of the Desperate Measures troupe, and local government, never compromising on the important aspects of protests by the troupe. At its best, local government celebrates and supports the community—for all its potency and, at times, dowdiness. Jo recognises this spirit, and highlights the way artists rallied (and continue to rally) with the broader community to generate change—manifest in City of Fremantle Council minutes, an object which features in Desperate Measures.

The artist I have subsequently come to know—in equal parts straight-talking and compassionate—is the one you will encounter below.

—Stirling Kain.

Stirling Kain: Tell me about your intention and your background as a curator, and as a researcher, and as an activist. I don't know if you consider yourself an activist, I haven't talked to you about that yet.

Jo Darbyshire: I prefer to call myself an artist-curator, because I think artists can be activists by their very nature. We're taught in art school to question things, to come up with alternatives, and to not be stopped. That's probably one of the best things about being an artist—you learn to go around obstacles and to think more laterally about problems. I think it's quite powerful to be an artist-curator.

SK: So for you, maybe 'curator' doesn't have that inherent sense of activism, but the word 'artist' does, and you include the sense of activism when you call yourself an artist-curator?

JD: In my mind, I like to think of the artist as being an activist. I mean, many artists are not, but putting 'artist' and 'curator' together, that is, for me, one of the great joys of life—when I'm allowed to curate an exhibition and I can use some of the skills that I have learned as an artist.

SK: I want to return to what we talked about a few weeks ago, when we were at the Fremantle Arts Centre, and one of the first things we talked about—how does a protest exhibition sit in a local government gallery context? Initially, I was thinking, ‘does the exhibition become less radical in that local government context, or does the gallery become more politically radical?’ And now I’ve seen your exhibition, I've been thinking that it really depends on the intent, and who's involved.

JD: It really depends on whether it's supported all the way up the line, and if you've got a manager or a person that's really supportive of the message being given, that is unimpeded, not sanitized. As soon as you sanitize anything, you kill it. Society is not sanitized, but people love to sanitize in museums, and they love to sanitize things in local government. City of Fremantle has been fantastic, because they trusted me—there's been no censorship and they're happy for this to be seen as a historical exhibition. But this exhibition is not trying to be political or controversial. I never try to be controversial. I just think history is controversial. It's how you interpret it, and when—the context.

I was asked to work with the curator Andre Lipscombe, and with the City of Fremantle Art and Civic Collections. The curators in the past would not have collected work, thinking that one day these works would be used in an exhibition about activism in Fremantle. So, they didn't really buy those works or acquire them for that purpose. But I think if you allow outside curators to come in, we can make meaning out of what is in those collections.

In this exhibition, we've also included a ceremonial plaque from one of the US nuclear warships that came in the ‘80s—and a hell of a lot of them did come to Perth and Fremantle. Most councils have these plaques from these US ships. And no one usually knows what to do with them. They're stuck in a cupboard somewhere, and then they're de-politicized—they're just a gift from that ship. So, to put them in a context—you've got the anti-nuclear protesters, showing their banners on the ship, which we've got photographs of—and to juxtapose the plaque next to it—is to show the connection between local government and the protests. They were welcomed by the council and the mayor, and then at the same time, they weren't welcomed by the local community. And quietly, I'm trying to make those connections visible to people and to say, ‘well, we're in exactly the same situation right now.’

SK: I've been thinking about a museological framework for protest exhibitions and using collections. I don't know if you saw the exhibition 1948: Palestine in Pictures, at Pakenham Street Art Space, with Cool Change Contemporary?

JD: Yeah, it was fantastic.

SK: It was really wonderful. And I felt it adopted a museological framework like Desperate Measures. And I wonder if that was informed by the fact that the people depicted, the Palestinian community, many of them had left their ancestral homes. The exhibition reflects what they were able to bring with them when they immigrated—small, flat objects like photographs. Reflecting on that exhibition, alongside Desperate Measures—what is it about using that museological framework and collections, within the context of a protest exhibition, that works so well? There's something particularly that you are drawn to, and I think that framework works really well in other protests exhibitions as well.

JD: What I liked about that exhibition—they used a whole range of objects and photos. They had vintage and contemporary photos, and vintage and contemporary objects. They put it together in a way that was more Installation than didactic interpretation. They also had sparse and beautifully curated text. They had quotes and video, and they also had a little bit of writing to put the exhibition in context. I love exhibitions like that—what I would call ‘encyclopedic’—using all the things that are available, to really draw people into the story.

You always need objects, I think, or really great photos—and this is where the visual arts come in—you're creating an opportunity for people to become bodily immersed in what they call a 'history exhibition.' Because history is often presented as didactic and dull—and sometimes it really can be. You can just kill history by how it's put together. But that exhibition, and I'm hoping the exhibitions that I do, try to make people bodily connected to what they're reading and what they're seeing. So, using text in a kind of visual way.

Sometimes you can't get to do that, because graphic designers tend to have a format. You know, they have the wall text, so they have the little label text that goes next to the object. I like to play around with those. I think that often the information that's in the little wall text is actually really vibrant and interesting.

SK: You definitely played with that in Desperate Measures, with the text being so physically large. And I also happened to see those conversations you had with the graphic designer right at the end. You were saying that the text in the panels was the incorrect size. And, on this occasion, that wasn't the graphic designer's fault, but that was a really important part for you.

JD: It is. I like to design exhibitions. I really have to have a visual idea in my head about the connection between that photo and the text next to it. You know, there are exhibitions where you just have wall label after wall label, and it's all the same, and it's all designed within a format. I prefer to prioritize the important text.

Cool Change Contemporary did this as well, with 1948: Palestine in Pictures. The bigger text: people are going to read that first. So, you make that the priority text. And then if people think 'I'm really interested in this little story', then they go into it further, and they might get the subtext, or they might read another little story around that, or they might understand a joke at the end.

Some people just walk into a history exhibition and they just want to look at the photos. So to have really interesting photos is fantastic. And in this show, I was really careful not to have too many photos, but to choose photos that were going to be super interesting for people, to draw people in and think, ‘oh, am I in the photo, or do I know someone in the photo?’ People love to interact with photographs.

SK: Something that I think about as an arts worker is that people often first go to the text, the explanation, and not the image. But in a history exhibition, you're saying that's reversed, and maybe it's because people think that they'll see themselves or someone they know, that they have a really personal connection to, in those images.

JD: I think people resist a lot of text. But if you are trying to get a story across you have to have facts, and you have to present them in a way that is not too didactic, but actually truthful—like if someone speaks in their own voice. That's also important.

SK: It's interesting that you say ‘truthful’. I think honesty is real when it includes people's voice. The way they speak, but then, their feelings as well.

JD: I agree with you. When you have people speaking, that's their truth. You can also have negative voices, and they are good to have in an exhibition about history, because they show what people were fighting against. So for instance, that little newspaper article in Desperate Measures, which headlines the then-Premier of Western Australia calling activists ‘evil’. That was just gold, because you could see the conservative forces that people were acting against. It's also quite humorous, because politicians often shoot themselves in the foot. You're just presenting the truth of what they said.

SK: And I'm thinking of that one quote from the Desperate Measures exhibition, one person talking about their experiences seeing Lesbian women on stage and performing.

JD: That was really fantastic. One of the Desperate Measures performers wrote to me—she said, ‘we weren't overtly into Queer stuff at that time, but we were exploring Feminism. And then, as part of that, we started to have Lesbian relationships.’ And she actually said, ‘when I was on tour to Adelaide, I became a Lesbian!’

SK: That's right, yeah! That's it.

JD: And so I wrote back to her and I said, ‘can I use that quote?’ Because it saves me having to be didactic. And saves me putting something into the text saying, 'oh, and Desperate Measures had lots of Lesbians involved', you know? It says a lot more than me just saying the bare information.

SK: How do you see protest happening today, as compared to Desperate Measures? What is the same, what’s different? For better or worse.

JD: I think there are definitely things happening, and in a different way to what Desperate Measures did. Hopefully with just as much fun, and also that commitment to it. That's going to be the crux in the future—how we work together as activists.

SK: You're absolutely right. I'm thinking that protest now looks very different to what Desperate Measures were doing—specifically, the artists I've seen protesting recently at fundraisers, they're performing in venues like the Buffalo Club.

JD: The aim of Desperate Measures was to do things publicly. I think everyone's gone a bit underground or online. There's certainly been consequences recently for artists that have even liked posts online. Big consequences for West Australian artists.

SK: I've been meaning to speak to you about that. I know recently in Sydney there was a climate protest to stop traffic on the Sydney Harbor Bridge, two of the protesters were charged.[1] Their jail sentences were successfully appealed, but one of the protesters was convicted of related charges. I'm interested in what you think—does that kind of response from the state influence how people protest?

JD: Absolutely. The protests that I have been arrested for—which were Roxby Downs uranium mine, Pine Gap in 1983, and, more recently, Roe 8—I would only get arrested when I knew that there was a big group of people getting arrested at the same time, and that we had pro bono lawyers ready to look after us, and bail us out. So I would not encourage anyone to go and do their own project and get arrested by themselves. Always do it with a group, and always have a lawyer.

All of these anti-nuclear [Project Iceberg] protesters that were arrested on US war ships in the ‘80s—they had lawyers, and those lawyers are still around. They organized themselves well, to keep things safe and to keep it non-violent. They all did ‘non-violent action training’, which was a weekend workshop where you learnt how to resist the police, but not to resist arrest.

SK: That reminds me of a conversation I had recently—someone commented that protesters and artists often have a really strong understanding of bureaucracy, because they have to navigate the bureaucracy.

JD: I think artists should break rules, but only when they know what the rules are. And only when it's better to break the rule than to keep it. I believe that's the same for activism.

SK: That's such a powerful statement. And you, personally, navigate bureaucracy by working within museum and art collections. That’s part of your protest and activism.

JD: I think it's great to invite artists to do exhibitions in museums. I mean, we just enliven them.

SK: Yeah, absolutely. We have spent time talking about that before—how archives can be living and breathing, but people have to imbue them with breath. They have to be used.

JD: That's beautiful. And a lot of people are afraid to let those archives be used in that way. Artists are not often welcomed into museums as curators. We have to claim that space. But once we are given the opportunity—we contribute to New Museology discourses, and we've really changed things in museums. Fred Wilsons' Mining the Museum exhibition, which showed slave shackles within a very traditional museum—he really changed the whole discourse. From there, other artists have worked with museums and really changed things as well. It's great to make history live. To make people realise: one, they're part of it, just in their ordinary, everyday lives. And two, the history that's not told is often the most interesting. When I did The Gay Museum…

SK: I'm so excited to talk about The Gay Museum! I love The Gay Museum!

JD: Did you see it?

SK: No, it was before my time, but I read your essay about it, and I loved it.[2]

JD: I knew that I wanted to go in and make an exhibition about gay and lesbian history in WA, but I couldn't until 2002, when the law changed.[3] Before that, institutions couldn't 'promote homosexuality'. As soon as we got that law reform, I went in and asked them, 'I want to do this'. Luckily, the Director of the Museum at the time, Dr. Gary Morgan, had just worked with Brooke Andrews at the Sydney Museum—so he said, 'okay'. It was quite a conservative Museum and there was a lot of resistance from the history department, from lots of people.

I had to be an enrolled master’s student to make The Gay Museum. They wouldn't let me just come in as an artist. But I had a fantastic supervisor called Mat Trinca, and he really helped me. And I got a lot of support from staff who were just waiting for someone to do something like this in the Museum. I wanted to bring something from every single department, to say: being gay, or being Lesbian, or Homosexual is not something that is outside of anything. We are part of everything.

For instance, they wanted me to bring in panels and stick them on the wall. And I said, no, no—I want to paint the walls black, and I want to have text panels really embedded in the space visually, so that we actually are part of the museum. It was a big project, but it was amazing. I worked with the community, and I worked trying to find empirical evidence. That was very difficult, because there was hardly anything—there was nothing collected in the Museum.

When I first went to the history department, I said that I wanted to physically look at all the collections. They said, no, no—you have to put search words into the catalogue. So, of course, what came up was one AIDS t-shirt, from South Australia. That was literally it.

SK: Ha!

JD: Then I found this crab—it was called a Shame-faced crab. And I thought, 'this is perfect.' So, I was able to talk about how museums think that they are objective, and yet they often name things with subjective meaning. So, I used that crab to talk about how Homosexuals were conditioned to feel shame, and how that affected their lives.

I found an electric shock machine in the Museum—which was in a medical section. It would have been kept for a medical display. But I put it near the Shame-faced crab, and talked about how gay men went through this terrible ‘conversion’ treatment. Right up to about 1978, they would be electrocuted with this machine to try and make them not gay; shocking them when they were shown pictures of naked men. That happened right here in WA, at Heathcote Hospital.[4]

And in that same exhibition, one of my art students at Edith Cowan University showed me his collection of ‘used soaps’, and I begged to use them. I displayed them next to the electric shock machine. All of these used soaps were not only beautiful as an installation, but they talked about trying to clean that ‘stain’ of Homosexuality, the shame that people felt in those days. So, taking things out of their normal context and using them metaphorically or poetically, or juxtaposing them with text that gave them a different context pertinent to gay and lesbian people, made a big difference.

SK: You would never have found the electric shock machine just by searching 'gay' and 'lesbian', or found it at all, unless you were looking for an electric shock machine. We've been talking about archives, and it's really important to think about how people might use them, in order to know how to categorise the objects. You have to future-craft in that way. And there are methodologies to researching and archiving that people can be educated in—but these things might change over time.

JD: Being able to have search words in an archive is important. You're right. However, I found the electric shock machine by looking physically through the collection. I would work for hours, searching through, and not find anything. And then suddenly you would come across something. And think, ‘wow, that's perfect.’ Like the Shame-faced crab was just perfect.

SK: Do you find that when you're making artwork as well, for example, paintings?

JD: Yeah.

SK: That's what I find in my practice, too. It can be a lot of nothing, nothing, nothing, and then you find something.

JD: Yeah. And that moment of joy, where it just comes.

SK: The curatorial research looks similar in the way it unfolds, to the making process of art.

JD: Putting yourself there, doing all the hard work to allow something to come—I think that's what painting is. And I think that's what curating an exhibition like this is. I did a lot of work contacting people about Desperate Measures and then asking them to send me stories.

A good example—Kati Thamo told me how she and Mandy Browne had ridden bikes up to Perth and did some graffiti on a public wall, which said, 'There once was a land full of laughing trees'. That graffiti stayed there for years, and someone made artwork about it, but Kati didn't know who. I searched online and found that we had a beautiful image in the State Art Gallery, and in the National Gallery as well. Screenprints had been made by Peter Clemesha, using a photograph he'd taken of the graffiti. That was one of those moments where I just thought, 'oh my God'. Peter Clemesha lives in Fremantle, and he never knew who made the graffiti. Kati and Mandy knew someone had made art about it, but they never saw it again. So, to bring them together was one of those great serendipitous stories about that time.

SK: It's interesting how these images relating to, and objects used for, protests are then acquired by institutions.

JD: They're starting to be. Initially, for Roe 8, they didn't want anything, but we collected everything ourselves, and we did work with the community. We made a database. There was a lot of art: posters, t-shirts, tea towels, banners. Even concrete Lock-on Barrels. We managed to save two of those out of the Roe 8 bush. One of those has gone to the WA Museum, and one has gone to the National Museum. I was pretty pleased to see the WA Museum collecting Disrupt Burrup stuff.

SK: I don't know how to feel about that yet.

JD: Well, they don't know how to exhibit them yet!

SK: I'm thinking about the Perspex that Joana Partyka spray-painted at the AGWA Disrupt Burrup Hub action from 2023. It was recently acquired by the WA Museum. She’s facing charges for her protest—but another state-funded institution only five-hundred meters away can acquire the object for its collection?

JD: But as Alec Coles [Director, WA Museum] said—the Museum's job is to collect both sides of an issue. In the past, they haven't. There are a lot of things that have never been collected, like women's history, and multicultural history. These were colonial institutions, and they looked at everything through that empirical lens. It's only since New Museology came on the scene—since the ‘80s and ‘90s—when people questioned the role of museums, that things have changed.

I think it's great that the Museum is collecting that protest material. It has to question itself as well. That's what happened in The Gay Museum. The museum was asked to question its own collecting practices, and its own curatorial practices. I think that was quite challenging for them, but they did. It really depends a lot on who's working in those places as well, as to what gets collected.

Desperate Measures: Art, Politics and Performance in Freo 1977 –1985, Fremanlte Arts Centre, 9 November 2024 – 27 January 2025.

—

Jo Darbyshire was born in 1961 in Perth, Western Australia. She studied Fine Arts at Curtin University in 1981, a Postgraduate Diploma at Canberra School of Art in 1991 and a Master of Creative Arts in Cultural Heritage at Curtin University of Technology in 2004.

Stirling Kain is an arts worker and artist in Perth (Boorloo). As an arts worker, she produces art festivals and events. Her photography practice involves film and darkroom techniques. Kain graduated with a Bachelor of Art (History of Art maj., History min.) from the University of Western Australia in 2020.

Footnotes:

1. See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/mar/15/climate-activist-deanna-violet-cocos-15-month-jail-sentence-overturned-on-appeal

2. See https://www.jodarbyshire.com/uploads/text-files/gay_museum_catalogue.pdf

3. See https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/prod/filestore.nsf/FileURL/mrdoc_7865.pdf/$FILE/Law%20Reform%20(Decriminalization%20of%20Sodomy)%20Act%201989%20-%20%5B00-00-00%5D.pdf?OpenElement

4. Tony Thomas, ‘Homosexuals and Perth’, The Critic, University of Western Australia, vol.8, no.10, 1968, p.94.

Images courtesy of the Fremantle Arts Centre.