At first, the unorthodox installation of Kieron Broadhurst and Ash Tower’s Border Chronicle at Goolugatup makes for uneasy navigation. Multiple short, shallow shelves litter the walls at irregular levels, interrupted occasionally by three large pin boards, and a low table stretches itself across one side of the room. There are small objects on the shelves and the table, and laminated pieces of paper pinned to the board—but it proves difficult to establish their material and just what they might represent. Some of the shelves are placed too high to have a good look at what sits atop them; to reach eye-level with others you need to almost land in the splits. Despite my attempts to maintain the nonchalant air appropriate to a critic I begin to feel a little lost, so I try my luck with the catalogue. Unable to make sense of the words and embarrassed by what feels like incompetence, I give up and proceed outdoors to listen to two ladies from Italy produce obscure noises as part of a separate event. With a bit of patience, I learn to love it, but I won’t be listening to it in my spare time.

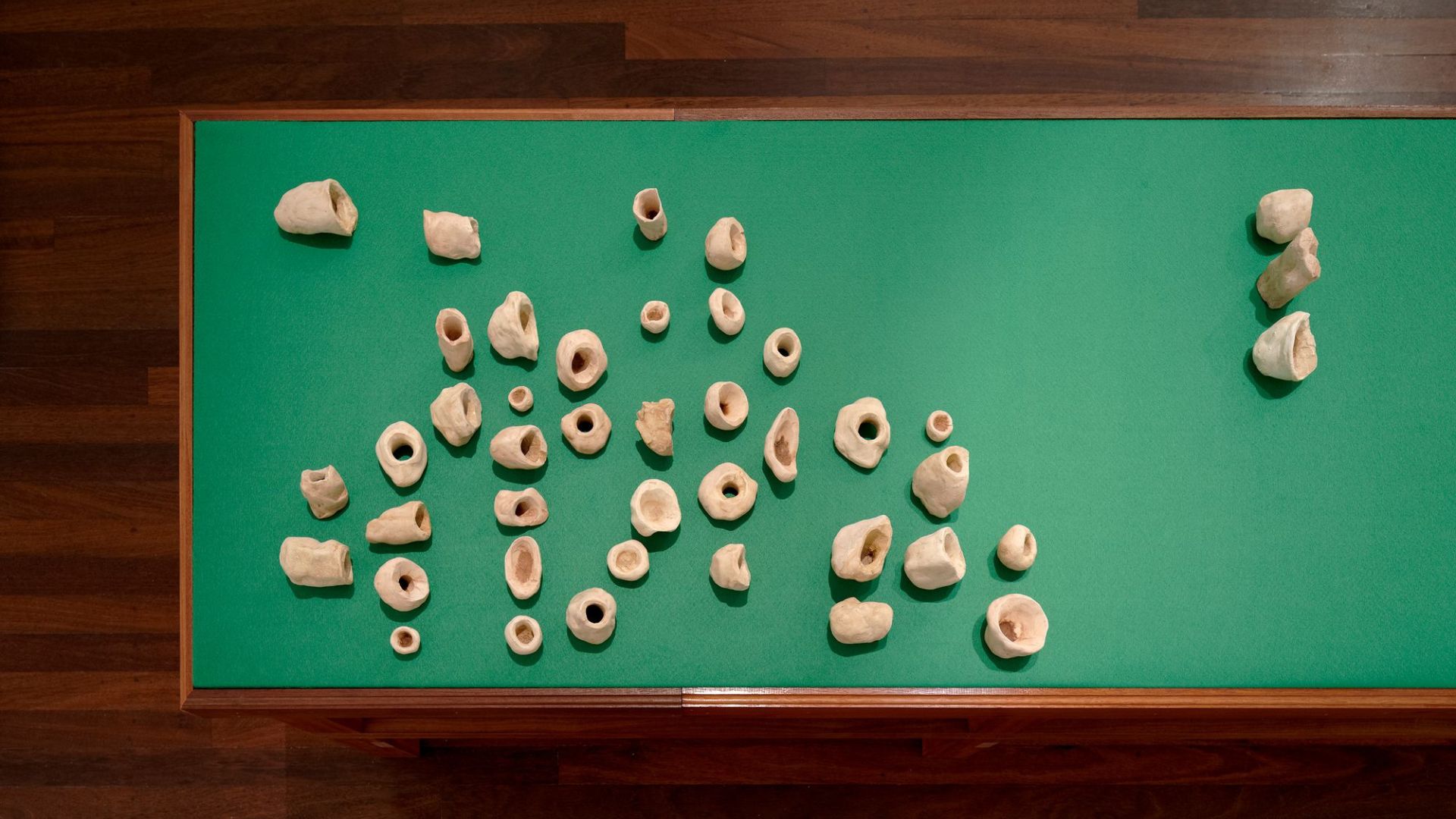

I revisit the exhibition a few more times, first for Broadhurst’s artist talk, and secondly with my pal Matt Marschall, who dresses himself in black from head to toe to “fit in”. The artist talk reveals that the inconsistent shelf placements allude to tide marks, spaces that have been ‘repeatedly flooded and then dried’.[1] This flooding is further signified through Tower’s watercolour and ink pieces, pinned up on the tacky-green felted boards. The archival scans of these works appear water-damaged—like they may have once been notes or drawings. Broadhurst mentions that he and Tower bickered about what the washed-out markings may represent.[2] The tea patinas on each ceramic work are suggestive of small pools that have evaporated over time. Each has been carefully placed upon the green felted puddle cut outs on the shelves or laid in a heap on the table. They look like seashells or lost treasures that have washed up on a deserted beach. Even Matt recognises that these objects are ‘kinda like shells’, simultaneously claiming that the work is ‘not unique on its own’, and that ‘they lay on the heavy conceptual stuff to make up for it’.

Although not inherently queer, Border Chronicle’s use of alternative exhibition and display techniques are reminiscent of those outlined by Nikki Sullivan and Craig Middleton in Queering the Museum (2020). Societal expectations directed towards museums are inherently rooted in the traditional museological practices enforced by dominant Western ideologies.[3] When these expectations are challenged through queer museum methods that encourage interpretation and meaning-making instead of factual information being spoon fed by an assumed ‘expert’,[4] many individuals, like my friend Matt, leave the exhibition feeling alienated. It has even been suggested that an absence of meeting these visitor expectations is associated with a lower intention to revisit said museum/s.[5] Gaining visitors being the main goal of most museums and art galleries means that such methods are fearfully avoided.

Matt feels that the heavy poetics in Broadhurst and Tower’s work makes the meaning less accessible, especially after he reads Jack Wansbrough’s catalogue essay with a furrowed brow. ‘Maybe you’re right, I don’t really understand’, he says. The aim of open-ended narratives in queer theory is to actually include a broader audience who have agency in making interpretations about, in this case art, through personal and unique contexts.[6] This process of experiencing museums, however, was proving difficult to popularise even before a world that is now beginning to rely on AI chat bots over original thought. There is such a desperate need to know something immediately. This need is consistently reinforced by the belief that ‘seeing is somehow equivalent to knowing,’[7] a belief that has been instilled by colonial and heteronormative ideologies within museum and exhibition settings, ‘reduc[ing] the ... self-expressive possibilities of all people’.[8] It therefore feels more important than ever for artists to utilise alternative museum and exhibition practices like the ‘novel arrangements’ and ‘non-conventional modes of display’[9] seen in Border Chronicle.

‘Oh, it’s supposed to be boring … not exciting’, Matt says with glee as he reads the summary of the exhibition. This obviously satisfies him enough and he asks if we can leave yet. But I have been waiting for him to mistakenly claim this victory. In some way, he is actually right. His overall lack-of-interest in the work at least enforces its attempt at referencing the mundanity of hobby and community museums.[10] At the same time however, the work hopes for its audience to notice the subtle metaphors and stories that these objects, images and supports have to offer. With no context of its own, it hopes that you will give it one. I wonder what it is about the work that Matt finds boring. I assume it may be the heavy repetition throughout the room. ‘There is good repetition and bad repetition … it is hard to say much about the latter beyond that it is, well, boring.’[11] But what makes good repetition good? Surely Broadhurst would not have spent as much time as I assume he did handmaking close to 400 ceramic pieces which he then repeatedly ‘dip[ped] in black tea’ for days on end,[12] only for his audience to respond with boredom. The ceramics, I feel, are like clouds: the closer you look, the more you notice their uniqueness. Some are shaped like tiny cups and bottles, others are like the bones of mysterious creatures.

Whilst thinking of clouds, I notice a similarity between the appearance of Tower’s watercolour and ink drawings—and more importantly the overall conceptual intentions of Border Chronicle (2025)—Alfred Stieglitz’s photographic series Equivalents (1925). The ‘intangible, constantly metamorphosing’ quality of clouds was ‘the ideal subject matter for a photographer interested in both metaphor and capturing the “real”.’[13] Through Stieglitz’s work we witness an exploration of personal philosophy that has been reflected through the reproduction of familiar subject matter abstracted through simple photographic methods such as zoom and long exposure.

Stieglitz’s photographs, Broadhurst’s ceramics and Tower’s drawings resemble things we have seen before. They beg us for our curiosity and imagination. As the audience, we each have the ability to draw connections between what someone has made and something we may have seen, thought, felt, or experienced in any form previously. This is a practice that feels key in preserving the heartbeat of contemporary art—and is one I hope to see encouraged more by our art museums and galleries.

Kieron Broadhurst & Ash Tower’s Border Chronicle ran from 5 April – 18 May 2025 at Goolugatup Heathcote.

Footnotes:

1. Broadhurst, Kieron. Unpublished artist talk. April 6, 2025, Goolugatup Heathcote.

2. Ibid.

3. Sullivan, Nikki, and Middleton, Craig. 2020. Queering the Museum. 1st ed. London: Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351120180

4. Ibid.

5. Trabskaya, Julia, Zelenskaya, Elena, Sinitsyna, Anastasia, and Tryapkin, Nikita. 2021. “Revisiting museums of contemporary art: what factors affect visitors with low and high levels of revisit intention intensity?” Museum Management and Curatorship 38 (2): 210-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2022.2073559

6. Ibid, 3.

7. Lehner, Ace. 2023. “GENDER/SEX THEORY: Feminist/Queer/Trans Theory and Trans Embodied Methodologies in Contemporary Art: An Intergenerational Dialogue on the Page.” In A Companion to Contemporary Art in a Global Framework, 1st ed., edited by Jane Chin Davidson and Amelia Jones, 377-297. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119841814

8. Ibid.

9. Goolugatup Heathcote. 2025. Border Chronicle Kieron Broadhurst & Ash Tower. Applecross: Goolugatup Heathcote. https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/61a5be0777ff7d68ce47f827/68088d2e86da548ea399a6c1_Roomsheet-GOO-APR2025-Digital.pdf.

10. Ibid.

11. Moller, Dan. 2014. “The Boring.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 72 (2): 181-191.https://www.jstor.org/stable/43282325

12. Ibid.

13. Diak, Heather A. 2016. “Clouded judgement: Conceptual art, photography, and the discourse of doubt.” In Photography and Doubt, 1st ed., edited by Sabine T. Kriebel and Andrés Zervigón, 253-274. London: Routledge. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/detail.action?docID=4748665

Images of Kieron Broadhurst & Ash Tower’s Border Chronicle, courtesy of Goolugatup Heathcote. Photography by Aaron Claringbold.

I revisit the exhibition a few more times, first for Broadhurst’s artist talk, and secondly with my pal Matt Marschall, who dresses himself in black from head to toe to “fit in”. The artist talk reveals that the inconsistent shelf placements allude to tide marks, spaces that have been ‘repeatedly flooded and then dried’.[1] This flooding is further signified through Tower’s watercolour and ink pieces, pinned up on the tacky-green felted boards. The archival scans of these works appear water-damaged—like they may have once been notes or drawings. Broadhurst mentions that he and Tower bickered about what the washed-out markings may represent.[2] The tea patinas on each ceramic work are suggestive of small pools that have evaporated over time. Each has been carefully placed upon the green felted puddle cut outs on the shelves or laid in a heap on the table. They look like seashells or lost treasures that have washed up on a deserted beach. Even Matt recognises that these objects are ‘kinda like shells’, simultaneously claiming that the work is ‘not unique on its own’, and that ‘they lay on the heavy conceptual stuff to make up for it’.

Although not inherently queer, Border Chronicle’s use of alternative exhibition and display techniques are reminiscent of those outlined by Nikki Sullivan and Craig Middleton in Queering the Museum (2020). Societal expectations directed towards museums are inherently rooted in the traditional museological practices enforced by dominant Western ideologies.[3] When these expectations are challenged through queer museum methods that encourage interpretation and meaning-making instead of factual information being spoon fed by an assumed ‘expert’,[4] many individuals, like my friend Matt, leave the exhibition feeling alienated. It has even been suggested that an absence of meeting these visitor expectations is associated with a lower intention to revisit said museum/s.[5] Gaining visitors being the main goal of most museums and art galleries means that such methods are fearfully avoided.

Matt feels that the heavy poetics in Broadhurst and Tower’s work makes the meaning less accessible, especially after he reads Jack Wansbrough’s catalogue essay with a furrowed brow. ‘Maybe you’re right, I don’t really understand’, he says. The aim of open-ended narratives in queer theory is to actually include a broader audience who have agency in making interpretations about, in this case art, through personal and unique contexts.[6] This process of experiencing museums, however, was proving difficult to popularise even before a world that is now beginning to rely on AI chat bots over original thought. There is such a desperate need to know something immediately. This need is consistently reinforced by the belief that ‘seeing is somehow equivalent to knowing,’[7] a belief that has been instilled by colonial and heteronormative ideologies within museum and exhibition settings, ‘reduc[ing] the ... self-expressive possibilities of all people’.[8] It therefore feels more important than ever for artists to utilise alternative museum and exhibition practices like the ‘novel arrangements’ and ‘non-conventional modes of display’[9] seen in Border Chronicle.

‘Oh, it’s supposed to be boring … not exciting’, Matt says with glee as he reads the summary of the exhibition. This obviously satisfies him enough and he asks if we can leave yet. But I have been waiting for him to mistakenly claim this victory. In some way, he is actually right. His overall lack-of-interest in the work at least enforces its attempt at referencing the mundanity of hobby and community museums.[10] At the same time however, the work hopes for its audience to notice the subtle metaphors and stories that these objects, images and supports have to offer. With no context of its own, it hopes that you will give it one. I wonder what it is about the work that Matt finds boring. I assume it may be the heavy repetition throughout the room. ‘There is good repetition and bad repetition … it is hard to say much about the latter beyond that it is, well, boring.’[11] But what makes good repetition good? Surely Broadhurst would not have spent as much time as I assume he did handmaking close to 400 ceramic pieces which he then repeatedly ‘dip[ped] in black tea’ for days on end,[12] only for his audience to respond with boredom. The ceramics, I feel, are like clouds: the closer you look, the more you notice their uniqueness. Some are shaped like tiny cups and bottles, others are like the bones of mysterious creatures.

Whilst thinking of clouds, I notice a similarity between the appearance of Tower’s watercolour and ink drawings—and more importantly the overall conceptual intentions of Border Chronicle (2025)—Alfred Stieglitz’s photographic series Equivalents (1925). The ‘intangible, constantly metamorphosing’ quality of clouds was ‘the ideal subject matter for a photographer interested in both metaphor and capturing the “real”.’[13] Through Stieglitz’s work we witness an exploration of personal philosophy that has been reflected through the reproduction of familiar subject matter abstracted through simple photographic methods such as zoom and long exposure.

Stieglitz’s photographs, Broadhurst’s ceramics and Tower’s drawings resemble things we have seen before. They beg us for our curiosity and imagination. As the audience, we each have the ability to draw connections between what someone has made and something we may have seen, thought, felt, or experienced in any form previously. This is a practice that feels key in preserving the heartbeat of contemporary art—and is one I hope to see encouraged more by our art museums and galleries.

Kieron Broadhurst & Ash Tower’s Border Chronicle ran from 5 April – 18 May 2025 at Goolugatup Heathcote.

Footnotes:

1. Broadhurst, Kieron. Unpublished artist talk. April 6, 2025, Goolugatup Heathcote.

2. Ibid.

3. Sullivan, Nikki, and Middleton, Craig. 2020. Queering the Museum. 1st ed. London: Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351120180

4. Ibid.

5. Trabskaya, Julia, Zelenskaya, Elena, Sinitsyna, Anastasia, and Tryapkin, Nikita. 2021. “Revisiting museums of contemporary art: what factors affect visitors with low and high levels of revisit intention intensity?” Museum Management and Curatorship 38 (2): 210-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2022.2073559

6. Ibid, 3.

7. Lehner, Ace. 2023. “GENDER/SEX THEORY: Feminist/Queer/Trans Theory and Trans Embodied Methodologies in Contemporary Art: An Intergenerational Dialogue on the Page.” In A Companion to Contemporary Art in a Global Framework, 1st ed., edited by Jane Chin Davidson and Amelia Jones, 377-297. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119841814

8. Ibid.

9. Goolugatup Heathcote. 2025. Border Chronicle Kieron Broadhurst & Ash Tower. Applecross: Goolugatup Heathcote. https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/61a5be0777ff7d68ce47f827/68088d2e86da548ea399a6c1_Roomsheet-GOO-APR2025-Digital.pdf.

10. Ibid.

11. Moller, Dan. 2014. “The Boring.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 72 (2): 181-191.https://www.jstor.org/stable/43282325

12. Ibid.

13. Diak, Heather A. 2016. “Clouded judgement: Conceptual art, photography, and the discourse of doubt.” In Photography and Doubt, 1st ed., edited by Sabine T. Kriebel and Andrés Zervigón, 253-274. London: Routledge. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/detail.action?docID=4748665

Images of Kieron Broadhurst & Ash Tower’s Border Chronicle, courtesy of Goolugatup Heathcote. Photography by Aaron Claringbold.