Under the existing dominant society… a true artistic activity is necessarily classed as criminality. It is semi-clandestine. It appears in the form of scandal.

—The Situationist Manifesto

There are lots of ways in our great democracy that you can protest lawfully, but to protest unlawfully in that manner has no place, I know the people of Perth will be rightly outraged with what they have seen.

— Basil Zempilas, Lord Mayor of Perth

Maniacs are emerging from their hovels at noon, howling vulgar slogans and wielding mashed potatoes, tomato soup, and superglue. The casualties of their indecency: the bullet-proof plexiglass and gilt frames of our finest art establishments. To thank for this exciting new phenomenon we have activist organisations such as Just Stop Oil, Extinction Rebellion, Last Generation, and the latest group Disrupt Burrup Hub, who have begun an activist campaign of scandalising interventions into the cultural life of Western Australia. So far they have targeted the Art Gallery of Western Australia, the Perth Police Centre, Parliament House, Optus Stadium, and Woodside’s Perth headquarters. Its members include ceramicist Joana Partyka, graphic designer Tahlia Stohlarski, and musicians Trent Rojahn and Emil Davey. As a result of their activities these artist-activists have faced significant state repression, everything from fines to full-on raids by WA Police’s special counter-terrorism unit (we all know our former Premier’s predilection for a loose definition of terrorism). Their first action garnered significant press attention in January 2023, when Partyka and Indigenous rights activist Desmond Blurton entered AGWA and stencilled the Woodside logo on top of Frederick McCubbin’s nationally renowned painting Down on his luck.

The carnival of reaction plays out the same way each time: How dare these freaks threaten the hallowed art museums? Won’t someone think of the culture! In chorus they howl a common-sense refrain, so often weaponised against agitators and activists, “We agree with their ideas but not their methods, go somewhere else!”. What an odd thing to say on a planet tilting towards catastrophe, where those who are at the wheel are more interested in garnering every scrap of profit than ensuring a habitable Earth. The tipping point for a hothouse Earth (+2℃) is currently slated for somewhere between 2050 and 2080, though this approximation is continually revised downwards as successive governments fail to keep to their patently inadequate international frameworks and conventions, themselves manufactured solely to placate an increasingly anxious public. Various mitigation strategies are trotted out year after year, usually “carbon” with words like “offset”, “capture”, “storage”, or “credits” annexed to it. We’ll doubtless see more of these, with each new proposal more farcical than the last.

In 2015 we got a glimpse behind the political veil, when Peter Dutton was caught off-guard by a hot microphone sharing a quip with Tony Abbott at the Pacific Islands Forum: ‘Time doesn’t mean anything when you’re, you know, about to have water lapping at your door.’ They know the scale of the crisis that’s facing the world—they just don’t care. While we hear less of these kinds of obscenities under a Labor government, they are clearly just as committed to climate disaster as the Liberals. We live in a period of historic attacks on wages and public services, in a time of massive wealth transfer from poor to rich. It’s all pretty glum, really. We know from history that the only way to change these things is to fight back, but how do we best do that today? Can art vandalism, actions by groups like Disrupt Burrup Hub and Extinction Rebellion, really change the world, and if not, then what can? The only way to begin to answer these questions is to turn to history, and attempt to sketch out a theory of vandalism.

Breaking things is fun. What’s more: it’s art. Destructions, erasures, effacements, defacements, replacements, and profanings are the little things that make life worth living. Simple pleasures like drawing a dick on a politician’s face in a café newspaper, concocting new and suggestive versions of church hymns and national anthems, or penning offensive latrinalia—these dynamic interventions sometimes find their way into the galleries and museums, where in place of their usual quiet anonymity we find a media spectacle. Art vandalism (or “iconoclasm”) has a long and storied career, and yet art critics have devoted little sustained energy to its examination. At worst you get criminological essays which collapse all destructive acts levelled at artworks into the—singularly classed—category of “property damage”. At best you get essays offering a gallerists perspective on art vandalism, such as Helen Scott’s synoptic PhD thesis Confronting Nightmares or Brian Dillon’s article Seven faces of the art vandal, which provide interesting case studies and posit potential categories of vandalism, but, again, do not engage in any kind of rigorous class analysis. Dario Gamboni’s 1997 book The Destruction of Art remains the only contemporary systematic attempt at a detailed history of iconoclasm and vandalism, however, his approach renders politics in a largely two-dimensional and top-down way, essentially eschewing class analysis like all the rest. Any examination of the aesthetics of iconoclasm / vandalism without a simultaneous critique of the broader politics of art production in its total context is doomed to this kind of flatness.

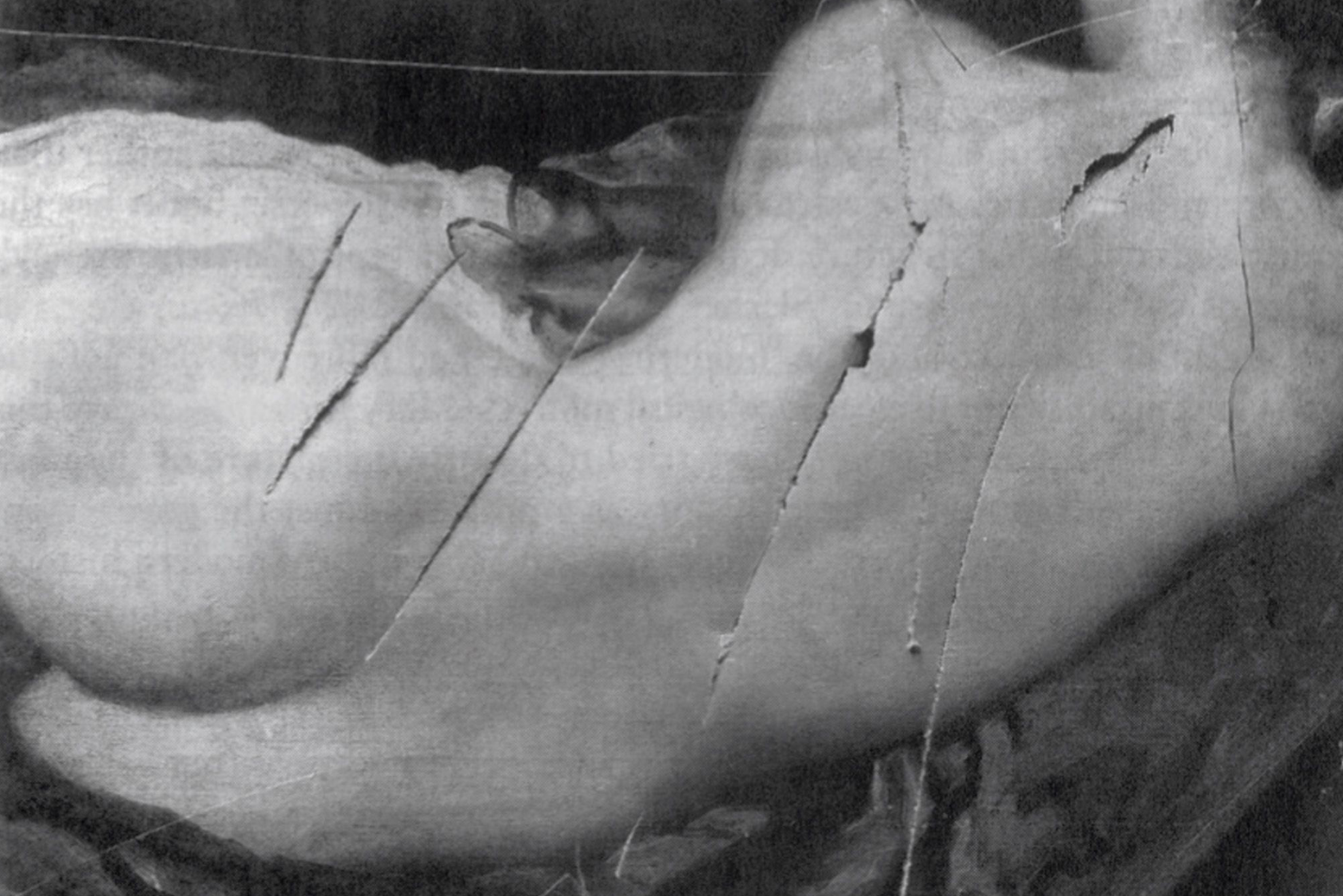

The first major example comparable to the present climate interventions is the (ad hoc) vandalism campaign conducted by the Womens Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1914, to which climate activists still refer today. In addition to pamphleting and street protests, the overwhelmingly middle-class suffragettes of the WSPU conducted arson and bombing campaigns, got in fist-fights with police, and (most famously) threw themselves on to horse-racing tracks. Other organisations, such as the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), were quick to distance themselves from such activities, in favour of mass working class organisation and demonstrations. In March of 1914, WSPU member Mary Richardson entered the National Gallery in London and, producing a meat cleaver from her coat, slashed several times at the Rokeby Venus. Best described by its former owner John Morritt as a ‘fine portrait of Venus’ backside’, the Venus had been paid for with a public subscription, including a key contribution by the lecherous King Edward the VII, to the tune of £45,000. Richardson had selected the Venus on account of its commercial and aesthetic value, and had prepared a statement for the press before the vandalisation, which read:

Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the WSPU, had been re-arrested by the British government a few days earlier, in a frail and emaciated state from repeated spells in Holloway prison. Richardson’s action inspired a wave of suffragette vandalism, with nine incidents damaging a total of fourteen paintings between March and the outbreak of World War I in July of that year, which marked the end of suffragette radicalism.

In response to the war the WSPU pivoted, and Emmeline Pankhurst became an icon of ultra-nationalist and pro-war politics, encouraging members to not only join the workforce, but also to join in the noble bourgeois pursuits of strikebreaking and union-busting. Mary Richardson would go on to take this reactionary politics to its logical conclusion, joining the women’s section of Sir Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists, along with several other former members of the WSPU, at one point saying that she was attracted by its ‘policy of Imperialism, and action combined with discipline’.[i] The class-divided women’s movement obtained a partial victory with the Representation of the People Act 1918, which expanded suffrage to include women over thirty, subject to a property qualification which excluded the poorest third of the population (those whose rent amounted to less than £5 annually). For the WSPU this was success enough to wind up the movement. This break was consistent with their middle-class base which, unlike the predominantly socialist NUWSS, was only ever really interested in suffrage for themselves, on the same terms as men. The pro-war pivot is ultimately explicable in a similar way: the middle-class WSPU ultimately shared many of the same imperialist interests as the ruling class. Clara Zetkin described best the difference between working class and bourgeois suffragists when she wrote:

Her later politics aside, Richardson’s tactic was drawn from a strain of mid-nineteenth century political activism: the “propaganda of the deed”[ii]. European anarchists in that period considered individual passivity, in a world built on the violence and coercion of the ruling classes, to be tantamount to participation, and embraced a campaign of terrorism against the ruling class not only as one political strategy among many, but as a moral imperative. Over time the propaganda of the deed became cloaked in new justifications—not only was it morally necessary, it also could have a stimulating influence on the masses to join in the anarchist cause. On the ground, however, the view was a little different. The anarchists carried out their attacks in a haphazard and disorganised fashion, and the State, predictably, responded with violence and repression, easily breaking whatever organisational capacity they possessed. Without a clear plan for broadening and deepening the struggle, each action simply corresponded to the outlook of its perpetrator, eventually resulting in isolation. This parochial and inward-facing approach lends itself to elitism: if no-one responds to your consciousness-raising call to arms, is it because they don’t care? To which the answer is often that the hard work of organising the movements necessary to bring about change has been neglected. This approach has been taken up most recently by Extinction Rebellion, whose particular brand of spectacular direct action contains echoes of the propaganda of the deed.

It is frequently reported that the public reacted with outrage to suffragette art vandalism. It is true that many newspapers published incendiary pieces about these incidents—labelling the suffragettes “insane”, “wanton” or “hysterical”—, but studies have tended to uncritically conflate this coverage with actual popular sentiment, citing the subscription which paid for the Rokeby Venus as evidence (given that it was composed of donations of all sizes from, it is inferred, all strata of society). It seems more likely to me that the subscription was drawn entirely from the bourgeoisie and aristocracy: the people who find greatest use for the gallery as an aesthetic and ideological tool. To quote the reactionary writer Louis Réau: ‘Beauty offends inferior beings who are conscious of their inferiority.’[iii] Digging a little deeper into the vandalism literature, its class dimensions quickly become apparent.

One of the most striking things about Helen Scott’s Confronting Nightmares is the sheer amount of vandalism that is motivated by financial distress, which is usually written off as the result of mental illness. In 1913 a man wearing a painters smock took a metal ruler to four paintings on display at the National Gallery. He was captured by the police-constable on duty, giving his name as Ernest Welch, a 40-year-old house-painter from Parkstone, Dorset.[iv] The prison doctor’s report stated, euphemistically, that Welch was ‘very confused, incoherent at times, and … generally in a melancholic condition. He has recently had a severe illness and a good deal of worry.’[v] Conditions for workers in the United Kingdom, particularly for labourers, had been on the decline since the economic peak in 1899.[vi] One 2011 study found that poverty rates among labourers reached almost 50% during this period. Is it such a stretch to think that Welch’s actions were a response to his impoverishment, rather than madness alone?

There are many other examples. In 1907, recently unemployed French governess Valentine Contrel vandalised Ingres’ The Sistine Chapel with scissors, giving the class rationale its clearest articulation: ‘It is a shame to see so much money invested in dead things like those at the Louvre collections when so many poor devils like myself starve because they cannot find work.’ R.A. Sigrist, an unemployed ship’s cook, who damaged Rembrandt’s Nightwatch in 1911 with a bread knife, did so under the belief that he was being prevented from finding employment by the authorities. In 1912 Prolaine Delarre, an impoverished Parisian seamstress, entered the Louvre and coloured in the lips of a Boucher, afterwards explaining:

A homeless man named Ugo Villegas threw a rock at the Mona Lisa in 1956, reportedly so that he could be imprisoned—at least then he would have somewhere to sleep. Robert Cambridge’s 1987 vandalism of a cartoon by da Vinci with a sawn-off shotgun was clearly motivated by social distress caused by the ‘political, social, and economic conditions in Britain’, though he later recanted this rationale after psychological treatment, calling his actions “a cry for help” instead. (I fail to see any meaningful distinction between his initial social distress and this born-again characterisation.) Beauty offends inferior beings who are conscious of their inferiority. Class-conscious, that is.

The scholarly emphasis on mere criminology and half-baked sociology[vi] obscures the classed nature of these events, along with other acts that are clearly products of alienation under capitalist society. The emphasis on an iconoclasm that is defined narrowly as property destruction bears much of the blame here. It is particularly difficult, to my mind, to equate the actions of Contrel, Villegas, or Cambridge, with the Islamic State’s destruction of Assyrian holy sites, the Russian state’s tacit approval of iconoclastic acts by Orthodox Christians, or the 1999 defacement of a black Madonna by a conservative Catholic which was so roundly approved of by then-New York mayor Rudy Giuliani. These latter acts have a top-down character, and serve to consolidate or perpetuate either the dominant or emergent ruling-class ideologies. Conversely, vandalism from below is aimed at dominant ideology, generally seeking to subvert or capitalise on the regime of property ownership. Through the painting, the sculpture, the gallery, the vandal is appealing to something, and that something should be determinative. I would propose an initial division between iconoclasm which reinforces dominant ideology, and vandalism which seeks to undermine it. It seems quite clear that there is a relationship between capitalist crisis and acts of art vandalism, which constitutes an appeal to the public at large; whereas iconoclasm’s only determinant is the moralistic outrage of its reactionary and conservative perpetrators—constituting, in essence, an appeal to (or by) the ruling class. There is a crucial difference also between Richardson’s destruction of the Rokeby Venus and acts of vandalism by the working class more generally: theirs was a cry of the oppressed, hers was a self-interested and middle-class militancy.

Can a straight line be drawn from the vandalism of the Rokeby Venus in 1914 through to Joana Partyka’s graffiti on Down on his luck in 2023? The answer depends on whether Disrupt Burrup Hub can transcend its elitism and reach out to a mass base, call protests, and push the struggle forward. Extinction Rebellion recently did just this in London, riding on a wave of British working class struggle. The dwindling of the School Strike for Climate movement left us all disheartened and demoralised, but this is not a good reason in and of itself to dismiss the political possibilities opened up by mass mobilisations, nor to claim that these movements are no longer possible. Groups like Disrupt Burrup Hub have the right idea when they say that we cannot trust the system to save the planet, but they are wrong to think that they can do it alone.

How should we understand movements like the Dadaists, the Situationists, and the Yes Men in a political history of art? And how do we take the lessons of past art movements, aesthetically and politically, into new and productive territory? This is the first article in Punctured, a series set on answering these kinds of questions at the intersection of history, politics, and art. The next article will look at debates on the purpose of art on the left after the 1917 Russian revolution.

The first article in the series Punctured 🚩

#2 coming soon...

[i] In fact, the motto of the WSPU was ‘Deeds not words’.

[ii] ‘Outrage at the National Gallery’, Times, 24 January 1913, p. 6.

[iii] L. Réau, Histoire du Vandalism, Paris, 1959, p. 16.

[iv] ‘Police Courts’, Times, 1 February 1913, p. 5.

[v] I. Gazeley & A. Newell, ‘Poverty in Edwardian Britain’, The Economic History Review, Vol. 64, No. 1, 2011.

[vi] See e.g. J. Kerr, ‘The Art of Violent Protest and Crime Prevention’, Arts, Vol 7(4) 2018; C. Cordess & Maja Turcan, ‘Art Vandalism’, British Journal of Criminology, Vol. 33(1) 1993; M.J. Williams, ‘Framing art vandalism: a proposal to address violence against art’, Brooklyn Law Review, Vol. 74(2), 2009; A. Nordmaker, T. Norlander, & T. Archer, ‘The Effects of Alcohol Intake and Induced Frustration on Art Vandalism’, Social Behavior and Personality, Vol. 28(1), 2000.

Image credits:

1. Still from a video released by Disrupt Burrup Hub that showed a woman spraypainting a Woodside logo on an artwork at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Photograph: HUB Disrupt Burrup Hub.

2. Punch a Monet by Tom Galle, Eiji Muroichi, and Dries Depoorter, available at http://punchamonet.gallery

3. The Rokeby Venus after Richardson’s Vandalism.

—The Situationist Manifesto

There are lots of ways in our great democracy that you can protest lawfully, but to protest unlawfully in that manner has no place, I know the people of Perth will be rightly outraged with what they have seen.

— Basil Zempilas, Lord Mayor of Perth

Maniacs are emerging from their hovels at noon, howling vulgar slogans and wielding mashed potatoes, tomato soup, and superglue. The casualties of their indecency: the bullet-proof plexiglass and gilt frames of our finest art establishments. To thank for this exciting new phenomenon we have activist organisations such as Just Stop Oil, Extinction Rebellion, Last Generation, and the latest group Disrupt Burrup Hub, who have begun an activist campaign of scandalising interventions into the cultural life of Western Australia. So far they have targeted the Art Gallery of Western Australia, the Perth Police Centre, Parliament House, Optus Stadium, and Woodside’s Perth headquarters. Its members include ceramicist Joana Partyka, graphic designer Tahlia Stohlarski, and musicians Trent Rojahn and Emil Davey. As a result of their activities these artist-activists have faced significant state repression, everything from fines to full-on raids by WA Police’s special counter-terrorism unit (we all know our former Premier’s predilection for a loose definition of terrorism). Their first action garnered significant press attention in January 2023, when Partyka and Indigenous rights activist Desmond Blurton entered AGWA and stencilled the Woodside logo on top of Frederick McCubbin’s nationally renowned painting Down on his luck.

The carnival of reaction plays out the same way each time: How dare these freaks threaten the hallowed art museums? Won’t someone think of the culture! In chorus they howl a common-sense refrain, so often weaponised against agitators and activists, “We agree with their ideas but not their methods, go somewhere else!”. What an odd thing to say on a planet tilting towards catastrophe, where those who are at the wheel are more interested in garnering every scrap of profit than ensuring a habitable Earth. The tipping point for a hothouse Earth (+2℃) is currently slated for somewhere between 2050 and 2080, though this approximation is continually revised downwards as successive governments fail to keep to their patently inadequate international frameworks and conventions, themselves manufactured solely to placate an increasingly anxious public. Various mitigation strategies are trotted out year after year, usually “carbon” with words like “offset”, “capture”, “storage”, or “credits” annexed to it. We’ll doubtless see more of these, with each new proposal more farcical than the last.

In 2015 we got a glimpse behind the political veil, when Peter Dutton was caught off-guard by a hot microphone sharing a quip with Tony Abbott at the Pacific Islands Forum: ‘Time doesn’t mean anything when you’re, you know, about to have water lapping at your door.’ They know the scale of the crisis that’s facing the world—they just don’t care. While we hear less of these kinds of obscenities under a Labor government, they are clearly just as committed to climate disaster as the Liberals. We live in a period of historic attacks on wages and public services, in a time of massive wealth transfer from poor to rich. It’s all pretty glum, really. We know from history that the only way to change these things is to fight back, but how do we best do that today? Can art vandalism, actions by groups like Disrupt Burrup Hub and Extinction Rebellion, really change the world, and if not, then what can? The only way to begin to answer these questions is to turn to history, and attempt to sketch out a theory of vandalism.

Breaking things is fun. What’s more: it’s art. Destructions, erasures, effacements, defacements, replacements, and profanings are the little things that make life worth living. Simple pleasures like drawing a dick on a politician’s face in a café newspaper, concocting new and suggestive versions of church hymns and national anthems, or penning offensive latrinalia—these dynamic interventions sometimes find their way into the galleries and museums, where in place of their usual quiet anonymity we find a media spectacle. Art vandalism (or “iconoclasm”) has a long and storied career, and yet art critics have devoted little sustained energy to its examination. At worst you get criminological essays which collapse all destructive acts levelled at artworks into the—singularly classed—category of “property damage”. At best you get essays offering a gallerists perspective on art vandalism, such as Helen Scott’s synoptic PhD thesis Confronting Nightmares or Brian Dillon’s article Seven faces of the art vandal, which provide interesting case studies and posit potential categories of vandalism, but, again, do not engage in any kind of rigorous class analysis. Dario Gamboni’s 1997 book The Destruction of Art remains the only contemporary systematic attempt at a detailed history of iconoclasm and vandalism, however, his approach renders politics in a largely two-dimensional and top-down way, essentially eschewing class analysis like all the rest. Any examination of the aesthetics of iconoclasm / vandalism without a simultaneous critique of the broader politics of art production in its total context is doomed to this kind of flatness.

The first major example comparable to the present climate interventions is the (ad hoc) vandalism campaign conducted by the Womens Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1914, to which climate activists still refer today. In addition to pamphleting and street protests, the overwhelmingly middle-class suffragettes of the WSPU conducted arson and bombing campaigns, got in fist-fights with police, and (most famously) threw themselves on to horse-racing tracks. Other organisations, such as the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), were quick to distance themselves from such activities, in favour of mass working class organisation and demonstrations. In March of 1914, WSPU member Mary Richardson entered the National Gallery in London and, producing a meat cleaver from her coat, slashed several times at the Rokeby Venus. Best described by its former owner John Morritt as a ‘fine portrait of Venus’ backside’, the Venus had been paid for with a public subscription, including a key contribution by the lecherous King Edward the VII, to the tune of £45,000. Richardson had selected the Venus on account of its commercial and aesthetic value, and had prepared a statement for the press before the vandalisation, which read:

I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history. I protest at the Government who are destroying [Emmeline Pankhurst], who is the most beautiful character in modern history… If there is an outcry against my deed, let everyone remember that such an outcry is hypocritical as long as they allow the destruction of Mrs. Pankhurst… the stones cast against me for the destruction of this picture are evidence against them as artistic as well as moral and political humbugs and hypocrites.

Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the WSPU, had been re-arrested by the British government a few days earlier, in a frail and emaciated state from repeated spells in Holloway prison. Richardson’s action inspired a wave of suffragette vandalism, with nine incidents damaging a total of fourteen paintings between March and the outbreak of World War I in July of that year, which marked the end of suffragette radicalism.

In response to the war the WSPU pivoted, and Emmeline Pankhurst became an icon of ultra-nationalist and pro-war politics, encouraging members to not only join the workforce, but also to join in the noble bourgeois pursuits of strikebreaking and union-busting. Mary Richardson would go on to take this reactionary politics to its logical conclusion, joining the women’s section of Sir Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists, along with several other former members of the WSPU, at one point saying that she was attracted by its ‘policy of Imperialism, and action combined with discipline’.[i] The class-divided women’s movement obtained a partial victory with the Representation of the People Act 1918, which expanded suffrage to include women over thirty, subject to a property qualification which excluded the poorest third of the population (those whose rent amounted to less than £5 annually). For the WSPU this was success enough to wind up the movement. This break was consistent with their middle-class base which, unlike the predominantly socialist NUWSS, was only ever really interested in suffrage for themselves, on the same terms as men. The pro-war pivot is ultimately explicable in a similar way: the middle-class WSPU ultimately shared many of the same imperialist interests as the ruling class. Clara Zetkin described best the difference between working class and bourgeois suffragists when she wrote:

… the liberation struggle of the proletarian woman cannot be—as it is for the bourgeois woman—a struggle against the men of her own class … The end-goal of her struggle is not free competition with men but bringing about the political rule of the proletariat.

Her later politics aside, Richardson’s tactic was drawn from a strain of mid-nineteenth century political activism: the “propaganda of the deed”[ii]. European anarchists in that period considered individual passivity, in a world built on the violence and coercion of the ruling classes, to be tantamount to participation, and embraced a campaign of terrorism against the ruling class not only as one political strategy among many, but as a moral imperative. Over time the propaganda of the deed became cloaked in new justifications—not only was it morally necessary, it also could have a stimulating influence on the masses to join in the anarchist cause. On the ground, however, the view was a little different. The anarchists carried out their attacks in a haphazard and disorganised fashion, and the State, predictably, responded with violence and repression, easily breaking whatever organisational capacity they possessed. Without a clear plan for broadening and deepening the struggle, each action simply corresponded to the outlook of its perpetrator, eventually resulting in isolation. This parochial and inward-facing approach lends itself to elitism: if no-one responds to your consciousness-raising call to arms, is it because they don’t care? To which the answer is often that the hard work of organising the movements necessary to bring about change has been neglected. This approach has been taken up most recently by Extinction Rebellion, whose particular brand of spectacular direct action contains echoes of the propaganda of the deed.

It is frequently reported that the public reacted with outrage to suffragette art vandalism. It is true that many newspapers published incendiary pieces about these incidents—labelling the suffragettes “insane”, “wanton” or “hysterical”—, but studies have tended to uncritically conflate this coverage with actual popular sentiment, citing the subscription which paid for the Rokeby Venus as evidence (given that it was composed of donations of all sizes from, it is inferred, all strata of society). It seems more likely to me that the subscription was drawn entirely from the bourgeoisie and aristocracy: the people who find greatest use for the gallery as an aesthetic and ideological tool. To quote the reactionary writer Louis Réau: ‘Beauty offends inferior beings who are conscious of their inferiority.’[iii] Digging a little deeper into the vandalism literature, its class dimensions quickly become apparent.

One of the most striking things about Helen Scott’s Confronting Nightmares is the sheer amount of vandalism that is motivated by financial distress, which is usually written off as the result of mental illness. In 1913 a man wearing a painters smock took a metal ruler to four paintings on display at the National Gallery. He was captured by the police-constable on duty, giving his name as Ernest Welch, a 40-year-old house-painter from Parkstone, Dorset.[iv] The prison doctor’s report stated, euphemistically, that Welch was ‘very confused, incoherent at times, and … generally in a melancholic condition. He has recently had a severe illness and a good deal of worry.’[v] Conditions for workers in the United Kingdom, particularly for labourers, had been on the decline since the economic peak in 1899.[vi] One 2011 study found that poverty rates among labourers reached almost 50% during this period. Is it such a stretch to think that Welch’s actions were a response to his impoverishment, rather than madness alone?

There are many other examples. In 1907, recently unemployed French governess Valentine Contrel vandalised Ingres’ The Sistine Chapel with scissors, giving the class rationale its clearest articulation: ‘It is a shame to see so much money invested in dead things like those at the Louvre collections when so many poor devils like myself starve because they cannot find work.’ R.A. Sigrist, an unemployed ship’s cook, who damaged Rembrandt’s Nightwatch in 1911 with a bread knife, did so under the belief that he was being prevented from finding employment by the authorities. In 1912 Prolaine Delarre, an impoverished Parisian seamstress, entered the Louvre and coloured in the lips of a Boucher, afterwards explaining:

I am miserably hungry and have been unable to find work. I often go to the Louvre, and the sight of the young woman in the picture with a happy smile and luxurious clothes maddened me. I decided to mutilate her hateful face in the hope that perhaps after that people would notice me and save me from starving.

A homeless man named Ugo Villegas threw a rock at the Mona Lisa in 1956, reportedly so that he could be imprisoned—at least then he would have somewhere to sleep. Robert Cambridge’s 1987 vandalism of a cartoon by da Vinci with a sawn-off shotgun was clearly motivated by social distress caused by the ‘political, social, and economic conditions in Britain’, though he later recanted this rationale after psychological treatment, calling his actions “a cry for help” instead. (I fail to see any meaningful distinction between his initial social distress and this born-again characterisation.) Beauty offends inferior beings who are conscious of their inferiority. Class-conscious, that is.

The scholarly emphasis on mere criminology and half-baked sociology[vi] obscures the classed nature of these events, along with other acts that are clearly products of alienation under capitalist society. The emphasis on an iconoclasm that is defined narrowly as property destruction bears much of the blame here. It is particularly difficult, to my mind, to equate the actions of Contrel, Villegas, or Cambridge, with the Islamic State’s destruction of Assyrian holy sites, the Russian state’s tacit approval of iconoclastic acts by Orthodox Christians, or the 1999 defacement of a black Madonna by a conservative Catholic which was so roundly approved of by then-New York mayor Rudy Giuliani. These latter acts have a top-down character, and serve to consolidate or perpetuate either the dominant or emergent ruling-class ideologies. Conversely, vandalism from below is aimed at dominant ideology, generally seeking to subvert or capitalise on the regime of property ownership. Through the painting, the sculpture, the gallery, the vandal is appealing to something, and that something should be determinative. I would propose an initial division between iconoclasm which reinforces dominant ideology, and vandalism which seeks to undermine it. It seems quite clear that there is a relationship between capitalist crisis and acts of art vandalism, which constitutes an appeal to the public at large; whereas iconoclasm’s only determinant is the moralistic outrage of its reactionary and conservative perpetrators—constituting, in essence, an appeal to (or by) the ruling class. There is a crucial difference also between Richardson’s destruction of the Rokeby Venus and acts of vandalism by the working class more generally: theirs was a cry of the oppressed, hers was a self-interested and middle-class militancy.

Can a straight line be drawn from the vandalism of the Rokeby Venus in 1914 through to Joana Partyka’s graffiti on Down on his luck in 2023? The answer depends on whether Disrupt Burrup Hub can transcend its elitism and reach out to a mass base, call protests, and push the struggle forward. Extinction Rebellion recently did just this in London, riding on a wave of British working class struggle. The dwindling of the School Strike for Climate movement left us all disheartened and demoralised, but this is not a good reason in and of itself to dismiss the political possibilities opened up by mass mobilisations, nor to claim that these movements are no longer possible. Groups like Disrupt Burrup Hub have the right idea when they say that we cannot trust the system to save the planet, but they are wrong to think that they can do it alone.

How should we understand movements like the Dadaists, the Situationists, and the Yes Men in a political history of art? And how do we take the lessons of past art movements, aesthetically and politically, into new and productive territory? This is the first article in Punctured, a series set on answering these kinds of questions at the intersection of history, politics, and art. The next article will look at debates on the purpose of art on the left after the 1917 Russian revolution.

The first article in the series Punctured 🚩

#2 coming soon...

[i] In fact, the motto of the WSPU was ‘Deeds not words’.

[ii] ‘Outrage at the National Gallery’, Times, 24 January 1913, p. 6.

[iii] L. Réau, Histoire du Vandalism, Paris, 1959, p. 16.

[iv] ‘Police Courts’, Times, 1 February 1913, p. 5.

[v] I. Gazeley & A. Newell, ‘Poverty in Edwardian Britain’, The Economic History Review, Vol. 64, No. 1, 2011.

[vi] See e.g. J. Kerr, ‘The Art of Violent Protest and Crime Prevention’, Arts, Vol 7(4) 2018; C. Cordess & Maja Turcan, ‘Art Vandalism’, British Journal of Criminology, Vol. 33(1) 1993; M.J. Williams, ‘Framing art vandalism: a proposal to address violence against art’, Brooklyn Law Review, Vol. 74(2), 2009; A. Nordmaker, T. Norlander, & T. Archer, ‘The Effects of Alcohol Intake and Induced Frustration on Art Vandalism’, Social Behavior and Personality, Vol. 28(1), 2000.

Image credits:

1. Still from a video released by Disrupt Burrup Hub that showed a woman spraypainting a Woodside logo on an artwork at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Photograph: HUB Disrupt Burrup Hub.

2. Punch a Monet by Tom Galle, Eiji Muroichi, and Dries Depoorter, available at http://punchamonet.gallery

3. The Rokeby Venus after Richardson’s Vandalism.