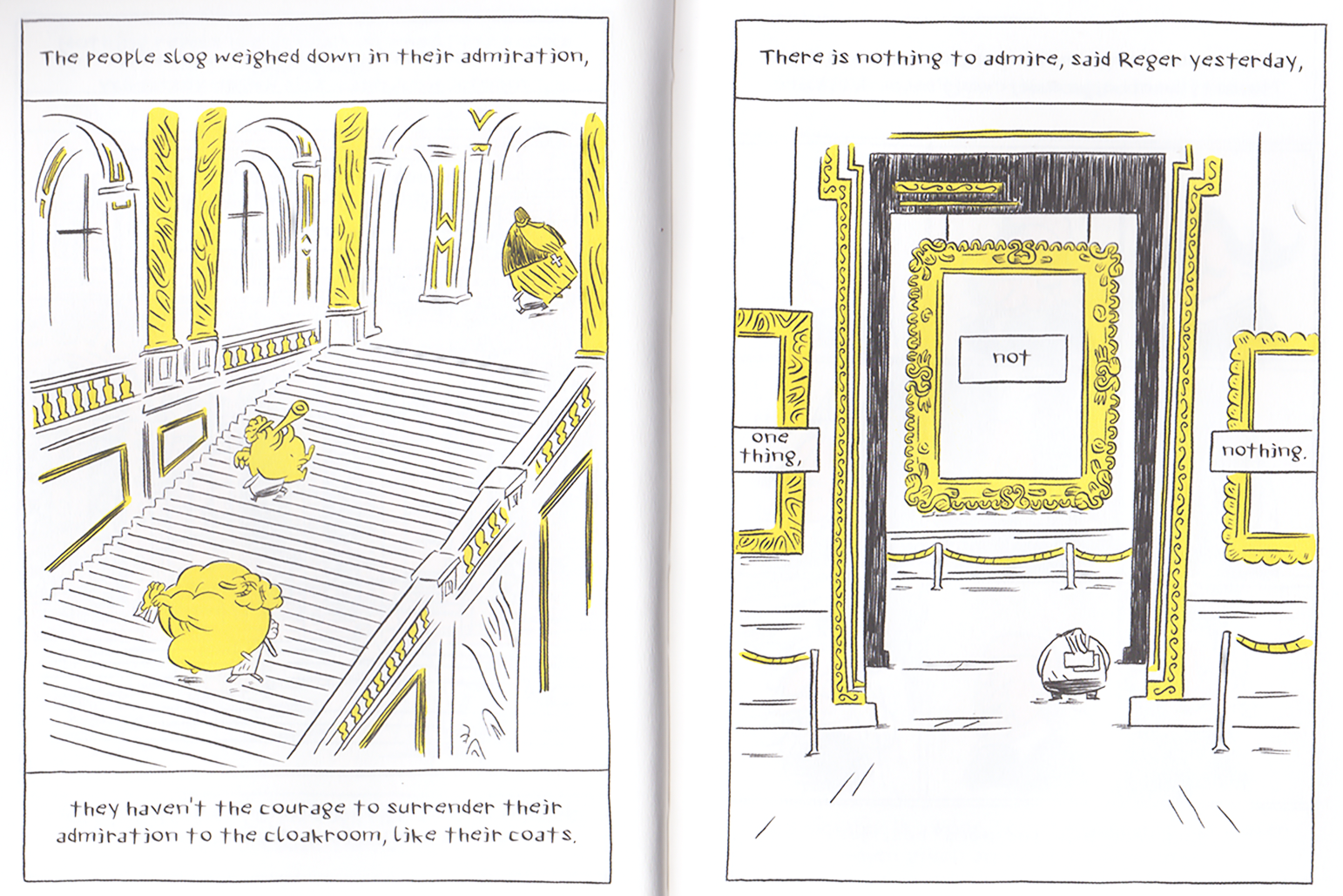

The admiration of the so-called educated ... is a positively perverse perverseness.

—Thomas Bernhard, Old Masters: A Comedy, 1985.

Years ago, in an undergraduate art history class, a lecturer advised me ‘only write about art that you love! Otherwise, what’s the point?’ This infuriated me. While silently cursing the class’s minimum attendance requirement, I wondered why this struck me as so acutely condescending and foolish. On an individual level, articulating and interrogating the contours of what we don’t like seemed crucial to me, not only for the purpose of establishing a genuine and informed appreciation of art and beauty, but in building a resistance to lazy or malicious appropriations.

Those who write about art shouldn’t be precluded from liking it, but, surely, they shouldn’t be fans. Negative criticism matters. The state of torpor induced by basking too long in the undeserved praise of others further enfeebles middling talent. This situation is not only a humiliating disservice to writers, institutions, and the public, but also to artists themselves. Ideally, the critic should wrest us from the stifling languor of unchecked mediocrity.

Today, dissatisfaction with the discourse on art and culture is rife in para-academic spaces. Rather than in journals or newsprint, robust art writing is championed by online platforms. Perth’s Dispatch Review is one example. As the marquee on their website declares, Dispatch brand themselves “Candid art criticism”. In what follows, I reflect on Dispatch’s first year of publication, considering its contribution to the Australian scene, and its place within global trends in criticism. With reference to several stirring reviews and their broader impact, I draw on the idea of negative criticism, the nature of the hostility it elicits, and the dangers of indulging too thoroughly. Due to the cultural hesitancy to criticise, to be a “hater”, the responses to Dispatch I draw from are primarily anecdotal, sourced from passing conversations and quips on social media. Admittedly, my appraisal of Dispatch’s work is directed by my own scholarly commitments and idiosyncrasies. However, I aim—as everybody should—to be objective and generous in my criticism, even when it is “negative”.

Dispatch operates on a weekly review schedule, inviting writers to respond to exhibitions in the vicinity of Perth or regional Western Australia. There are recent national precedents for this format. Most obvious is Melbourne’s Memo Review, which has been running since 2017 and has recently expanded to platform Sydney-based art and writing. But outside Australia’s major cultural capitals of Sydney and Melbourne, art scenes are constricted, making it more challenging to facilitate a culture of critical discourse. Coincidentally, Brisbane also has an equivalent, one year Dispatch’s senior. Described on its website as ‘a love letter to Queensland art and artists,’ Lemonade Letters to Art boasts some stand out reviews by writers like Kyle Weise and Adam Ford. However, its treacly branding—reminiscent of the platitudinal rhetoric of a Sunday paper’s “Arts and Culture” section—betrays a quaint regionalism that is reinforced by the bulk of its content.[1] As Western Australia’s relative isolation is comparable to Queensland’s “double displacement” from both national and international centres, to quote Rex Butler’s diagnosis, it’s all the more striking that Dispatch has facilitated a critical edge.[2]

The inaugural review by Sam Beard, one of the founding editors, set the tone. Published in April 2023 “Being Realistic” interrogates a contentious journalistic response to Beijing Realism (11 February – 26 March 2023) published a month prior by ArtsHub.[3] Beard deftly dismantles the original review, revealing its inconsistencies and oversights, a critical exercise that illuminates the nuances of the exhibition, the context of Asian art in Australia, and the failings of the current culture of complaint. Beard laments:

I thoroughly enjoy reading criticism that cuts deep, takes a side, advocates a point, and encourages me to rethink, reconsider, and, ultimately, to question art and ideas. Pickup and Lei’s ArtsHub article was a missed opportunity […]

The review ends with the simple statement ‘well- considered art criticism matters.’ Rather than following its sunshine state counterpart, Dispatch’s agenda aligns with the more senior Memo, which was similarly founded by an independent collective of art scholars committed to, as their website explains, filling ‘a gap in quality art criticism ... offering critical perspectives from a new generation of art scholars, writers and artists.’[4] And indeed, from the first review, Dispatch has demonstrated a commitment to critical and unapologetic commentary on art and culture, inevitably drawing the ire of some.

Some of the most compelling reviews Dispatch has published shed light on the intricacies of WA’s “art ecosystem”, such as Aimee Dodds’ ‘Bizarrely, a Biennale’ which examines the perplexing context of Bunbury Biennale and the regional translation of cosmopolitan “cutting edge” insights. Matching Dodds’ precision, many reviews interrogate the role and function of smaller, artist- run initiatives (ARI) in Perth. Of note is ‘Disneyland, Paris, Ardross and the artworld’ by Darren Jorgensen. The review considered Daniel Argyle’s Plastic ● Concrete at Dave Attwood’s Disneyland, Paris; an ARI located in the Perth suburb of Ardross. In this review, Jorgensen foregrounded the art world’s subsumption of radical values during ‘an era of anti-capitalism in the contemporary artworld’ and the symbiotic relationship between artist-run spaces and large state-funded institutions. It’s a compelling counter to conventional knowledge that rigidly upholds the subversive potential of independent spaces. And yet, Instagram commentary targeted the review for allegedly failing to address “anti-capitalism”. Likely established by the conventions of journalism in the social media age, readers are today wired to respond to formulas and assess a writer’s ability to repeat and synthesise the usual talking points. Increasingly, if a writer doesn’t address a topic in a very direct, box-ticking fashion—even if it’s clear to a discerningreader that the writer is deliberately negating the topic or raising it only to address the nuances of context— then the reader, like a studious tutor marking an essay alongside a tabled rubric, is emboldened to find fault.[5]

While a few humble debates have sparked on Instagram, some Perth locals have speculated about the potential overlap between members of Dispatch’s editorial board and those behind the now defunct Art Hysterical meme page: an Instagram account that lampooned Western Australia’s central art world figures and institutional controversies. Regardless of whether there is any truth behind this,[6] the impulse to insistently conflate the two outlets betrays the cynical desire to paint two very different forms of rhetoric—quippy memes and long-form art criticism—as the same, or to suggest that the indulgence in one must necessarily inform the other.

This is a symptom of a broader trend in public life that encroaches on criticism: surveillance-mindset. As Michel Houellebecq argues, the drive to constantly monitor others is a defining feature of the contemporary capitalist subject.[7] In turn, an artwork or text isn’t judged in isolation, but assessed alongside the person, or people, that created it. If this sounds dubious, consider the inverse. How often is a negative comment on another’s artwork met with therebuff “they are actually really nice!” as if this “niceness” disqualifies critical or unflattering commentary. And so, when somebody is perceived as not nice, the author or artist is rigorously screened for any possible ideological impurities or transgressions. The things they have done in public—and increasingly also in private—can be used to silence robust discourse on their work or permit an author to retreat from a considered appraisal. It’s a useful strategy for those unwilling, or unable, to engage with work beyond superficial, context-laden readings, ready to resort to personal attacks to cover their own hopeless inability to engage sincerely and deeply with art and ideas.[8]

Indeed, to accuse another of cruelty and vindictiveness while eschewing one’s own capacity for such behaviours is a strong play. Memes are the work of “trolls” or devil’s advocates, or provocateurs, not respectable creative class subjects. Due to the former’s associations with macho egos and deliberate insensitivity, the speculative conflation is a neat way of dismissing strident commentary.

However, the aversion to uncloaked criticality has deeper roots. As Barbara Ehrenreich noted in her book Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class (1990), the middle class subject (the primary demographic in the art world) prides themself on their ability to regulate their emotions, a distinguishing quality they believe separates them from the uncouth working class.[9] Managed through therapeutic practices, their love of administrative strictures manifests in their emphasis on emotional control, and in interpersonal relations which are subject to risk management in pursuit of mutually beneficial professional outcomes. This does not provide a good environment to make or discuss art.[10]

One recent manifestation of this tyranny of kindness is the promotion of “care ethics” in art and curatorial practices: a turn that apparently celebrates community-minded approaches and relationships forged in the gallery space. Sounds nice! But what about art? A common refrain for curators and writers who extoll care ethics is to rehash the etymology of the word curate, which comes from the Latin cura meaning “care”. As is often the case when etymological research passes through the soft hands of the reactive philistine, this emphasis is quite literalist and selective. Nevertheless, it conveys a truth: Ironically, those who champion “care” in curating generally don’t care about art. This is why it’s so easy for the care-pilled to sideline critical work for good vibes and networking activities.

Indeed, art criticism is often employed as an extension of networking, and any deviation from untempered praise is regarded with suspicion. A few years ago, an internationally celebrated Australian artist emailed me in anger about a positive, though not gleeful or flowery, review. They were shocked to discover that I had written this without consulting them! as though it were a violation for me to write about their work without having them explain it to me first (and, presumably, direct my “interpretation”). What does this say about art criticism in Australia? That, rather than an obvious and egregious conflict of interest, such an arrangement is now protocol?[11]

The interactions between artists, critics, institutions, and the public are more carefully managed than it first might seem. Indeed, art spaces are deftly aware of the power of the saccharine for reputational management. Case-in-point, in “Sweet sweet pea”, Beard analyses the strategic use of “playfulness” by a highly regarded Perth commercial gallery. Buffered by a caveat excusing his anecdotal “vibe check”, Beard unpacks Sweet Pea’s atmospheric echo of the ARI, cultivated by a more experimental, young, and fun energy than the comparative sterility and seriousness of commercial spaces. He explains: ‘I perceive sweet pea’s “sincere playfulness” as twee: a combination of democratising playfulness and aggrandising earnestness which codes the gallery as both egalitarian and accomplished.’ As Beard notes, this cultivated hybridity is, in fact, an established model. Neon Parc in Melbourne, forexample, straddles a similar line. As he recounts, Beard didn’t have knowledge of these precedents until after he formulated his thesis, which was informed by the relationship between Sweet Pea and a small selection of other local art spaces. In a sense, Perth’s relative isolation, and constricted art world, might provide a petri dish for thinking through art world conventions, especially with the support of a like-minded set.

The most notable critical exchange prompted by Dispatch began at the close of its first year of publication with Max Vickery’s review of Roberta Joy Rich’s The Purple Shall Govern (3 November – 31 December 2023) at Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. In the review, titled “What We Memorialise”, while appreciating Rich’s generative comparison between the political turmoil and impact of South Africa’s apartheid and segregation in Australia’s colonial history, Vickery offered a brilliantly detailed interrogation of the potential oversights of Rich’s exhibition and the discourse it imbibed. ‘In focusing narrowly on the political rights gained under liberal democracy,’ Vickery summarises in the conclusion, ‘the broader context of the fight for better economic conditions for everyday people is obscured.’

Vickery’s review wasn’t damning, but rather even- handed, giving due attention to the place of class politics in ending apartheid in South Africa. And yet, weeks later, Melbourne-based un projects published a review of the exhibition by Timmah Ball that unwaveringly defended Rich’s exhibition from criticism levelled by “a recent review”, obviously Vickery’s. Ball’s criticism centred primarily on Vickery’s discussion of exhibited footage concerning Nelson Mandela’s visit to Australia in 1990. In his original review, Vickery expressed disappointment that Mandela’s eschewal of working class concerns wasn’t explored further, but only suggested by juxtaposed archival footage. Ball’s review follows standard procedure, giving the artist the benefit of the doubt, and drawing on the context provided by the artist/gallery. Any ambiguity in the exhibition, Ball explains, is intentional. It’s great that Ball entered a dialogue with Dispatch. This is what a lively culture of art criticism looks like. A rejoinder from Vickery followed. Without Ball’s prompt, we wouldn’t have this extended exploration of the limits and false promises of political art and institutional critique. Not only did Vickery’s rejoinder provide the space for a nuanced and thorough analysis of his original claims about art’s political potential, and the class-blindness exhibited by the hot names of decolonial theory,[12] but an astute, long-overdue critique of an exemplary sample of industry supported writing.

Vickery’s review in particular signals Dispatch’s alignment with a culture of critical writing that has emerged in the past few years. Though the obvious comparison is Memo Review—and perhaps also The Manhattan Art Review—there are other art-aligned publications which are not so much precedents as examples of parallel thinking. The critical edge boldly forwarded by Dispatch writers—Vickery, Jorgensen and Francis Russell in particular—aligns with the project of Nonsite.org (2011-), an online, open access journal whose editorial board includes prominent figures such as the divisive American art historian Michael Fried, literary theorist Walter Benn Michaels, and political scientist Adolph Reed Jr. The latter two have respectively authored The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality (2006), and Class Notes: Posing as Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene (2001). This is a compelling grouping. The nexus of their concerns—regarding art, politics, and the neoliberal bureaucratisation of good intentions—is what makes the publication the perfect ground to interrogate how art, obfuscatory language, and covert institutional and political agendas collide today, making the creative class complicit. A respect for seriousness and intellectual debate (and its current deficit) similarly inspired another American publication titled The Point (2008-), and the United Kingdom’s more controversial Compact (2022-).

Perhaps it seems that I’ve deviated from talking about art criticism, but I am trying to demonstrate a cultural turn. Two decades ago, Benjamin Genocchio described art criticism as prose formed ‘under the pressure of deadlines [...] not a polished disquisition but a lively, hurried response to an object or exhibition.’[13] I doubt Genocchio’s definition applies to the longer-form online reviews offered by publications like Dispatch and Memo Review. Rather than written in the hours between the media preview and the public exhibition opening, writers for these platforms often labour a little longer over their reviews, offering something more than a hastily written, one-note response. Unlike reviews in newspapers, there is at least the pretence that these online reviews will remain easily accessible. Indeed, some serve as the primary literature on emerging artists.

The same frustrations that have inspired platforms like Nonsite.org seem to drive a lot of new art criticism. In 2023, Australian academic Simon During damningly declared that Australian universities are “demoralised” under the reign of neoliberal managerialism. The University, once the so-called “ivory tower” preserving the traditions of philosophy, literature, and art history, has practically forfeit these foundational commitments. As During explains, in the humanities ‘Traditional disciplines ... are now often regarded by both managers and students not as bodies of practice and scholarship built up over centuries, but as strictures from which to be freed.’[14] Accordingly, a trend emerges today. Those that really love art history are being edged out of—or are voluntarily retreating from—institutional settings where genuine investment in a discipline is treated as baggage to be jettisoned.

Online art and cultural criticism pick up the slack, as do atomised, terminally online autodidacts and anons populating sites like WordPress and Substack. Indeed, it feels like a rare, clandestine meeting to encounter people who genuinely engage with art history or literature. Though it’s still sometimes imagined that the University classroom or common area facilitate such generative meetings, it’s not that likely. Chance conversations of this nature are more likely to present at parties, pubs, or online, infused with an electric charge akin to that shared by those earnestly enthusiastic comic-book nerds who congregated in basements or conventions in the days before social media, or the music freaks on local radio stations who host, or religiously tune into, grave-yard segments dedicated to their niche interest. This comparison was inspired by Francis Russell, a regular Dispatch contributor who has himself recently retreated from academia. His astute review of COBRA’s Story of eggs (bird gallery for bird), an exhibition hosted by Bill’s PC, compared the “the curatorial practices of the hobbyist or pop-culture collector” to the globally networked, niche interests of contemporary artist run spaces. “It is arguable that the loaning of artworks between these physically small and yet internationally networked exhibition programs is closer to the act of friends loaning each other cards”, Russell explains. And indeed, like the adult nerds frequenting conventions and internet forums, for artist-run- and para- academic spaces alike, the motivation is often (though not always) purely driven by enthusiasm, rather than monetary gain. Refining and defending sensibilities in a competitive and impassioned environment, many in these spaces pursue their love of art, philosophy, or literature purely as hobbies that eat up their free time and are subsidised by unrelated employment.

In a statement that captures the tenor of these forums and their frustrations, Dodds encourages “punching downward” to keep bad art from rising.[15] Such a statement recalls the late Dave Hickey’s warnings about “our new motto” of fairness, which he saw as synonymous with mediocrity.[16] Art was better, he asserts, before we started encouraging people.[17] I agree with Dodds/Hickey. But as negative critics I think we should be careful with this suggestion, lest it fall into clumsy hands. Today, there’s a lot of bad, industry supported art. Many emerging artists are just following leader. I wonder if it’s unreasonable to expect the fresh crop to be better when so many art world successes are oh so punchable?[18] Yet, Dodds’ point resounds.

As Jorgensen notes, Dodds’ call to action recalls a bygone idea of art criticism. To varying degrees, this tone resonates across Dispatch. To contextualise this, we’ll return to the lessons of Dave Hickey. In many public lectures in the last decade of his life, Hickey talked about how he began writing art criticism. Along with figures such as Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, and Lester Bangs, he championed what we now call New Journalism, a genre that wed personal narrative with journalistic convention in a flowing prose style. Perhaps surprisingly, Hickey denied any innovation on his part. Rather, he claimed to be ripping off Victorian social reportage. ‘Go back,’ he advises, ‘and find somebody that you really like, and steal shit from them ... this is a process which I have certainly followed ... it’s called going back to the moment right before it started sucking.’[19] Such a method goes against the now rather standard belief in the arts that the cultural offerings of the past are obsolete, and that any interest in “the canon” is nostalgic or, worse, reactionary (“the return”, yikes!) Today, the tendencies of New Journalism are rife in our culture of narcissism, across auto-fiction, personal essays, post-Vice journalism, and social-media. In other words, it’s started sucking. Accordingly, Dispatch writers rarely defer to personal anecdotes, unless they are obviously relevant, and they don’t rely on an account of their visit to the gallery, or the bigwigs they saw at the exhibition opening, as a crutch to frame their reviews. Instead, Dispatch takes cues from “before it started sucking”, seemingly straddling the early days of New Journalism and the culture of serious, rigorous criticism it countered, where something was at stake and writers weren’t afraid to make broad statements and define—and argue for—their preferences.[20]

When Hickey was asked “why be a critic” in a 1999 interview, he answered:

Well, for the same reason that you do anything in culture—you want your views to prevail. You want to win. That is, you have a view of culture with which you are comfortable ... and you are always, I think, arguing in favour of a world that is more like that. And you want to win.[21]

There you have it. Dispatch have an idea of a better world, and want to win.

Tara Heffernan is an art historian and critic. Her work concerns modernism and the avant-gardes, conceptual art and the lineage/s of the New Left.

Footnotes:

1. Lemonade Letters intentionally courts this style, celebrating accessibility and an intentional eschewal of technical language, while still, somewhat contradictorily, positioning itself as a specialised, art world platform. The official website explains: “Lemonade aspires to be accessible, engaging, experimental, concise, humble, exploratory, passionate and jargon-free.” Louise R. Mayhew, “Lemonade is art criticism for the Sunshine State”, Lemonade Letters, n.d.

2. Rex Butler, Double Displacement: Rex Butler on Queensland Art 1992- 2016 (Brisbane, Institute of Modern Art, 2018).

3. See Jo Pickup and Celina Lei, “Curators’ responsibilities in spotlight as Chinese audiences feel ‘let down’”, ArtsHub, 24 March 2023.; The curators of the exhibition also published a response. See Darren Jorgensen and Tami Xiang, “Chinese art in Australia: Beijing Realism and the ethics of exhibition making”, ArtsHub, 12 April 2023.

4. The editors, “About Memo”, Memo Review, n.d.

5. This kind of person often unselfconsciously defer to celebrity thinkers as if they are the ultimate authority on a topic. “Oh my God, have you read David Graeber?!”, “Check out Sarah Ahmed!”, “I love Adam Curtis!” and so on.

6. While Sam Beard is rumoured to be connected, he neither confirmed nor denied his role.

7. Michel Houellebecq, Quelques mois dans ma vie: Octobre 2022 – Mars 2023 (Paris: Editions Flammarion, 2023), 84-86.

8. I am not suggesting that “good” artists who have done terrible things should be excused. Great art criticism can emerge if a writer provided they have sincere motivations—can locate the continuity between an artist’s transgressions and their expression in their art. What I am arguing is that the art, and the artist, are not inextricably connected. Moreover, assuming that good people make good art and bad people make bad art is not only foolish, but dangerous. Remember, when convicted murderer Jack Unterweger created admirable art, his talent convinced the Austrian literary elite that he was rehabilitated, leading to his release and subsequent murders. No doubt, this is an extreme example, but it’s telling.

9. Barbara Ehrenreich, Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class (New York: Harper Perennial, 1990), 51–52.

10. If anything verging on negative is said, it is typically expressed in cowardly, backhanded compliments. These comments exist in a protective ambiguous zone where nobody can be held accountable for their cruelty as it cannot be definitively defined or proven, nor can the aggressor make any substantial or important argument.

11. The number of reviews written by people who are friends with the artists or have an even more pronounced relationship with them (such as student/thesis advisor) is demonstrative of the apparently sanctioned corrosion of journalistic ethics to the detriment of art criticism. No doubt, these crossovers are often unavoidable. The art world is small, particularly in Australia. But it is suspicious that it’s now common for a writer to nearly exclusively write about, and promote, people in their inner circle.

12. Vickery summarises the dubious suggestion embedded in a bell hooks quote featured in Ball’s review: “For hooks, the problem isn’t the exploitation of the working class, it’s the elitism of the rich.”

13. Benjamin Genocchio, “Scrubbing Up: The Art of Art Criticism”, in The Art of Persuasion: Australian Art Criticism1950-2001, edited by Benjamin Genocchio (Sydney: Craftsman House, 2002), 9.

14. Simon During, “Friday Essay: Simon During on the demoralisation of the humanities and what can be done about it”, The Conversation, 15 July 2022; Similarly, Harold Bloom warned of the marginalisation of literary studies in academia, which he defended—not as some kind of snobbish propaganda—but as a necessary forum for thinking and learning in ways that challenge the mind and facilitate critical engagement with the world around us. Bloom saw encroaching philistinism in academia as promoting “a state of another kind of poverty”, a poverty of the imagination. Harold Bloom, “Harold Bloom interview on “The Weston Canon” (1994)”, YouTube, uploaded 7 June 2016, interview from Charlie Rose first aired on 29 December 1994, 10:00 – 11:00.

15. Aimee Dodds quoted in Darren Jorgensen, “Abstract art, DMT capitalism and the ugliness of David Attwood’s paintings”, Dispatch Review.

16. Dave Hickey, “Glasstire Presents: Dave Hickey, part 3 of 4: Administrated Art History”, Glasstire TV, 14 January 2014, footage of a lecture recorded 14 December 2013, 20:20 – 21:20, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7sxq8328tA.

17. Dave Hickey, “Dave Hickey: The God Ennui”, School of Visual Arts, 28 May 2021, footage of a lecture recorded 9 September 2009,41:08 – 42:12.

18. Though this is different to thought-out, negative criticism, punching down is also already rife in the art world. Like any neoliberal industry where credentialism is king, hostility finds its outlet in punishing underlings. Take the art school experience, for example. If you went to art school, you’ll remember seeing stars getting picked. Undesirable, typically lower class, non-cosmopolitan subjects are quickly sidelined while art-prac tutors and lecturers—who often vie for the same “emerging art” prizes as their more precocious students—form alliances with those they deem potential threats. These cool vampires, ready to sap the youth from the latest batch of air-headed trendies, know how precarious their own position is, and how valuable creating and maintaining hierarchies becomes in such a climate.

19. Dave Hickey, “Dave Hickey: The God Ennui”, 29:29 – 29:50.

20. More evidence of the cross-over: Beard’s “Weird Rituals” enthusiastically discusses Thomas Wolfe’s The Painted World.

21. Dave Hickey, interview with Terry Gross, “Defending Norman Rockwell”, Fresh Air, WHHY, 11 November 1999, 05:54-06:22.

Image: Nicolas Mahler’s adaptation of Thomas Bernhard’s Old Masters: A Comedy. Seagull Press.