Katie Glaskin’s world is full of spirits. This holds true both for her artistic and anthropological work, whether it be her discurses on shinto shrines, examinations of Bardi mortuary rituals in north-west Australia, or Seek Wisdom, her marvellous recent exhibition at Gallows Gallery in Mosman Park. In her anthropological work, Glaskin is part of what has been called the “ontological turn”, a current within the discipline which seeks to overturn many of its basic frameworks. The ontological turn is characterised by investigations into categories of being. Instead of adopting the customary worldview which reduces practices such as folk magic or shamanism to mere charlatanry at worst or dogmatic tradition at best, the ontological turn seeks to understand these practices on their own terms, as constitutive of entire and complete worlds which frequently do not adhere to the more rigid Cartesian approach which predominates in the societies descended from western Europe.

For its practitioners, worlds are produced from categories which—though capable of wide variation—possess an elementary or essential quality. Put simply, they are the most basic categories into which reality may be divided. The concept of personhood, for instance, is a human universal, in that it is practically impossible to exist as a human being without it. Adherents of the ontological turn argue that the category of personhood is capable of containing more than just the mind and body. It may be “extended” into other domains which a Eurocentric approach would consider illogical. Totemism is an example of this, wherein the person includes a particular animal or entire species of animal, a specific place or diffuse geographical feature, or even other persons living or dead.

All of the above is helpful to keep in mind when visiting Glaskin’s exhibition, as the works explore a topic on which she has written extensively: extinction. Seek Wisdom consists of eighteen paintings of roughly the same size, detailed studies of the shifting moods and hues of the University of Western Australia’s Crawley campus. The works are displayed in a well lit, small, but ample and open space in a simple and effective manner. Four of the paintings hang from suspended planes in the windows at the front of the gallery, such that, whether inside or outside, it feels as if the paintings are reaching out into the world, entangled in it. While this seems largely a product of spatial constraints, the effect is fitting.

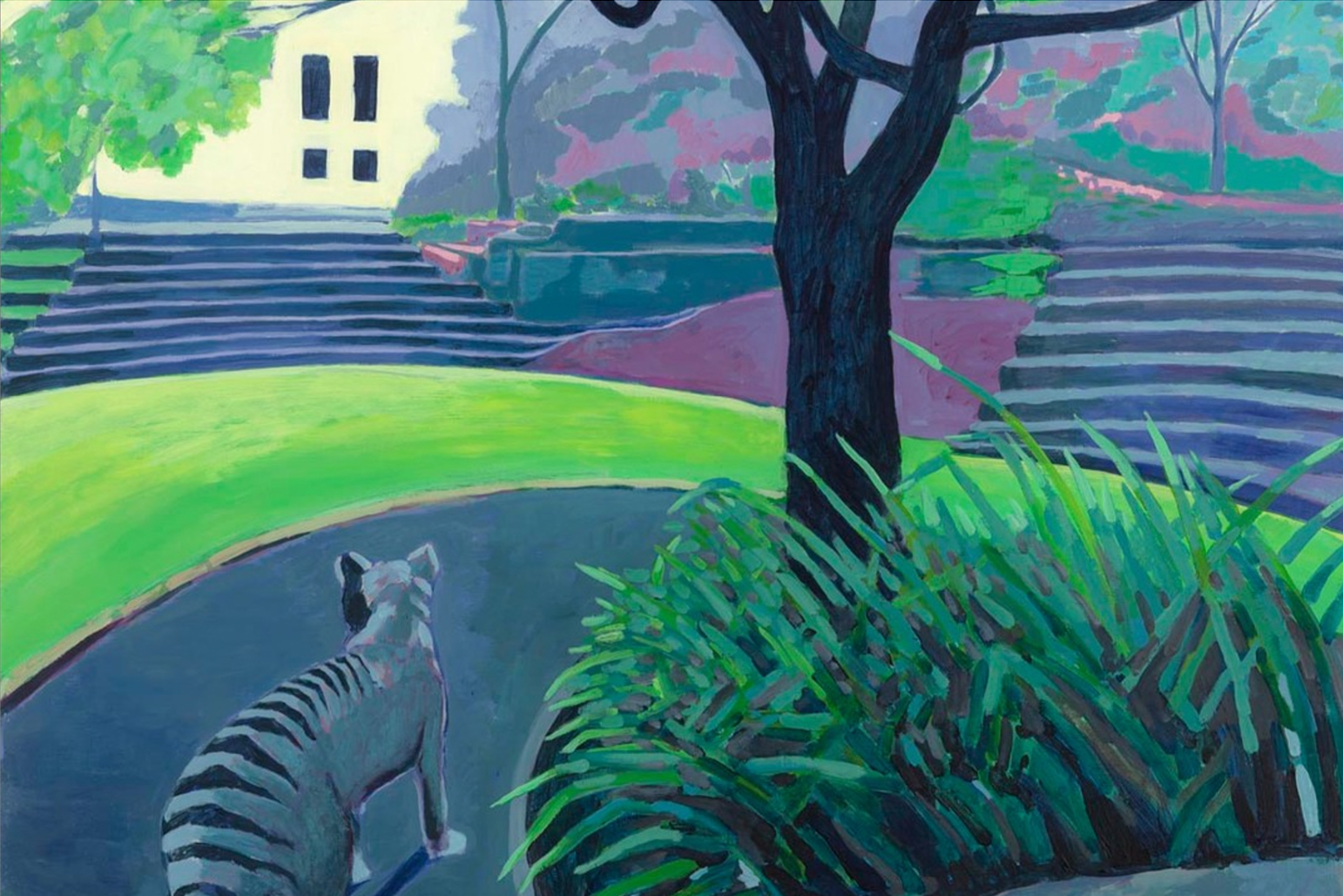

At first these works appear cartoonish, the worn beige sandstone of UWA rendered in bright pinks, greens, and blues. It is as if repeated exposures have captured afterimages burned into the retina at the peak of the day. Closer examination reveals each painting to be delicately worked, bright areas are overlaid with multiple layers of varied transparency, and the shadows are dappled and textured with thick, almost impasto brushstrokes. Glaskin’s palette obscures a subtle temporal warping. Her effulgent colours, almost fluorescent, are the colours of imagination. But something about them is impossible. Shadows of the late afternoon appear in the landscapes of mid-day; the dissolving gloam of dusk is accompanied by sharp-edged shadows. In Intimations, the polished concrete courtyard of the Social Sciences Building glistens and reflects as if wet with rain, and yet the buildings themselves sizzle with the heat of summer. Times and seasons blur and merge, compressed together into a single contradictory timescape.

Almost every one of these time-warped landscapes features a thylacine. They appear in different incarnations, as ghostly imprints left on UWA’s decidedly colonial lawns in Public Secret, looming over sandstone buildings in Overstory, or scandalous red graffiti in Witness and Understory. The thylacine lurks, much as it does in the consciousness of many Australians, as a symbol of extinction in connection with colonisation. The origin of Glaskin’s affinity with the thylacine lies in her anthropological background. In her 2021 article ‘Extinction, Inscription and the Dreaming’, Glaskin examines the ontology of extinction, drawing upon extensive rock art and ethnographic evidence to show that thylacines persist (or in some cases had persisted) as totem and rite across the continent:

Glaskin’s thylacines are meditations on the tantalising possibilities of different ontological frames, and on the contradictions arising from their conjunction.

In contrast, Parable, Class Act, and See No Evil feature the familiar sight of UWA’s irascible peafowl, in varying states of shabbiness and glory. Peafowl were introduced onto the campus by celebrated WA mining industrialist Sir Laurence Brodie-Hall in 1975. Brodie-Hall was exactly the kind of inhuman wretch one would expect from the mining industry. He despised unions, speaking of ‘engineering’ the Great Western Consolidated Mining (GWCM) company town in Bullfinch against ‘industrial unrest’. A cursory search of Trove showed that during his tenure at GWCM (1951–1958) there were at least seven accidental mining deaths at their Copperhead gold mine. While no violations of then-existing mining regulations were ever found, the fact that each accident had almost precisely the same cause is more than illustrative. GWCM was in financial ruin by the early 1960s, even with the aid of generous state subsidies, losing an estimated £3.5 million. For this extravagant and costly failure Brodie-Hall was rewarded with several directorships, a position as chair at the Chamber of Mines, and a knighthood. During his time as the latter he sacked engineering lecturer Andrew Corbyn from the WA School of Mines in Kalgoorlie after Corbyn released a report critical of the poor safety standards applied to Australian uranium production. A terrible man, like so many terrible men now lauded by our institutions; a terrible man whose legacy is terrible peacocks. It’s almost too perfect.

The Crawley campus is the ground on which these two forces interact. The thylacine as a symbol of the ontological peculiarities of extinction; the peacock as a symbol of institutions and wealth. Their more conventional implications are, of course, also engaged, the thylacine standing in for disappearance, destruction, and neglect; and the peacock standing in for flamboyance, preening, and preference. Both are conceptually united by their colonial histories, and submerged in the architecture of Western Australia’s first university.

There is no denying that this exhibition is informed by Glaskin’s experience at UWA during the 2021 restructure, when Vice-Chancellor Amit Chakma was flown out of the bloodbath he left at the University of Western Ontario to take a hatchet to the university. His restructure cut deep. An emphasis on teaching over research has almost annihilated academic careers in the traditional sense, and the anthropology major was decimated. This is a process playing out at universities globally. Universities have always had close relationships with industry. Historically they were places for the rich to send their heirs to learn the airs and graces of aristocratic society; their contemporary function under capitalism is to produce a layer of skilled workers and middle-class professionals. During our neoliberal period, characterised by austerity, degrees superfluous to this process are easily whittled away in favour of those with entrenched economic relationships with industry. UWA has always assiduously devoted itself to the needs of capitalist and state interests, whether they be agricultural, mineral, or defence. Their enthusiastic embrace of the arms industry in the wake of the AUKUS deal is a product of the same tendency which led to the restructure. Glaskin’s paintings are not of UWA, they are of its clashing idealisations, visions through rose-tinted spectacles, lamentations of the university’s petty interests, examinations under a harsh summer sun—but always with an eye to ostentation and extinction.

Photographs of Katie Glaskin’s exhibition Seek Wisdom, held at Gallows Gallery, courtesy of the artist. (Note, these images have been cropped to fit.)

For its practitioners, worlds are produced from categories which—though capable of wide variation—possess an elementary or essential quality. Put simply, they are the most basic categories into which reality may be divided. The concept of personhood, for instance, is a human universal, in that it is practically impossible to exist as a human being without it. Adherents of the ontological turn argue that the category of personhood is capable of containing more than just the mind and body. It may be “extended” into other domains which a Eurocentric approach would consider illogical. Totemism is an example of this, wherein the person includes a particular animal or entire species of animal, a specific place or diffuse geographical feature, or even other persons living or dead.

All of the above is helpful to keep in mind when visiting Glaskin’s exhibition, as the works explore a topic on which she has written extensively: extinction. Seek Wisdom consists of eighteen paintings of roughly the same size, detailed studies of the shifting moods and hues of the University of Western Australia’s Crawley campus. The works are displayed in a well lit, small, but ample and open space in a simple and effective manner. Four of the paintings hang from suspended planes in the windows at the front of the gallery, such that, whether inside or outside, it feels as if the paintings are reaching out into the world, entangled in it. While this seems largely a product of spatial constraints, the effect is fitting.

At first these works appear cartoonish, the worn beige sandstone of UWA rendered in bright pinks, greens, and blues. It is as if repeated exposures have captured afterimages burned into the retina at the peak of the day. Closer examination reveals each painting to be delicately worked, bright areas are overlaid with multiple layers of varied transparency, and the shadows are dappled and textured with thick, almost impasto brushstrokes. Glaskin’s palette obscures a subtle temporal warping. Her effulgent colours, almost fluorescent, are the colours of imagination. But something about them is impossible. Shadows of the late afternoon appear in the landscapes of mid-day; the dissolving gloam of dusk is accompanied by sharp-edged shadows. In Intimations, the polished concrete courtyard of the Social Sciences Building glistens and reflects as if wet with rain, and yet the buildings themselves sizzle with the heat of summer. Times and seasons blur and merge, compressed together into a single contradictory timescape.

Almost every one of these time-warped landscapes features a thylacine. They appear in different incarnations, as ghostly imprints left on UWA’s decidedly colonial lawns in Public Secret, looming over sandstone buildings in Overstory, or scandalous red graffiti in Witness and Understory. The thylacine lurks, much as it does in the consciousness of many Australians, as a symbol of extinction in connection with colonisation. The origin of Glaskin’s affinity with the thylacine lies in her anthropological background. In her 2021 article ‘Extinction, Inscription and the Dreaming’, Glaskin examines the ontology of extinction, drawing upon extensive rock art and ethnographic evidence to show that thylacines persist (or in some cases had persisted) as totem and rite across the continent:

This account suggests that in Aboriginal cosmologies, the disappearance of a species (in embodied form) does not indicate a final end, any more than the death of a person, from within this perspective, is understood as an end to a person’s very being, with the continuation of their existence involving different dimensions of the person…

Glaskin’s thylacines are meditations on the tantalising possibilities of different ontological frames, and on the contradictions arising from their conjunction.

In contrast, Parable, Class Act, and See No Evil feature the familiar sight of UWA’s irascible peafowl, in varying states of shabbiness and glory. Peafowl were introduced onto the campus by celebrated WA mining industrialist Sir Laurence Brodie-Hall in 1975. Brodie-Hall was exactly the kind of inhuman wretch one would expect from the mining industry. He despised unions, speaking of ‘engineering’ the Great Western Consolidated Mining (GWCM) company town in Bullfinch against ‘industrial unrest’. A cursory search of Trove showed that during his tenure at GWCM (1951–1958) there were at least seven accidental mining deaths at their Copperhead gold mine. While no violations of then-existing mining regulations were ever found, the fact that each accident had almost precisely the same cause is more than illustrative. GWCM was in financial ruin by the early 1960s, even with the aid of generous state subsidies, losing an estimated £3.5 million. For this extravagant and costly failure Brodie-Hall was rewarded with several directorships, a position as chair at the Chamber of Mines, and a knighthood. During his time as the latter he sacked engineering lecturer Andrew Corbyn from the WA School of Mines in Kalgoorlie after Corbyn released a report critical of the poor safety standards applied to Australian uranium production. A terrible man, like so many terrible men now lauded by our institutions; a terrible man whose legacy is terrible peacocks. It’s almost too perfect.

The Crawley campus is the ground on which these two forces interact. The thylacine as a symbol of the ontological peculiarities of extinction; the peacock as a symbol of institutions and wealth. Their more conventional implications are, of course, also engaged, the thylacine standing in for disappearance, destruction, and neglect; and the peacock standing in for flamboyance, preening, and preference. Both are conceptually united by their colonial histories, and submerged in the architecture of Western Australia’s first university.

There is no denying that this exhibition is informed by Glaskin’s experience at UWA during the 2021 restructure, when Vice-Chancellor Amit Chakma was flown out of the bloodbath he left at the University of Western Ontario to take a hatchet to the university. His restructure cut deep. An emphasis on teaching over research has almost annihilated academic careers in the traditional sense, and the anthropology major was decimated. This is a process playing out at universities globally. Universities have always had close relationships with industry. Historically they were places for the rich to send their heirs to learn the airs and graces of aristocratic society; their contemporary function under capitalism is to produce a layer of skilled workers and middle-class professionals. During our neoliberal period, characterised by austerity, degrees superfluous to this process are easily whittled away in favour of those with entrenched economic relationships with industry. UWA has always assiduously devoted itself to the needs of capitalist and state interests, whether they be agricultural, mineral, or defence. Their enthusiastic embrace of the arms industry in the wake of the AUKUS deal is a product of the same tendency which led to the restructure. Glaskin’s paintings are not of UWA, they are of its clashing idealisations, visions through rose-tinted spectacles, lamentations of the university’s petty interests, examinations under a harsh summer sun—but always with an eye to ostentation and extinction.

Photographs of Katie Glaskin’s exhibition Seek Wisdom, held at Gallows Gallery, courtesy of the artist. (Note, these images have been cropped to fit.)