The dark recesses of The Strelley Mob exhibition at John Curtin Gallery are inviting, split in two by the narrow

corridor which leads from one gallery space to the other. At one end lies a

room full of projected multimedia works, while the other features iconic

Pilbara paintings. The two are thematically linked by the Strelley strike

story, and lived experiences from the 1940s into the present. The show has a

meandering, museum-like layout. Viewers are directed past multiple glass cases

which present an assortment of sketchbooks, Strelley press produced materials,

and objects such as Spearim Jimmy’s metal yandy. The yandy stands out in this

show both as the only object without a printed overlay, and as an emblem of

itinerant miners and Strike Mob across the West. [1] Metal yandies, such as

these in the show, are adaptations of the wooden ones used by Aboriginal people

for seed processing, transformed first into sorters of precious metals and key

tools of self-determination. [2] The space at the other end of the corridor

displays four videos produced by Vladimir Todorović on large screens. Their

sequential rotation encourages the viewer to move through the dark space to

consume its cosmology, memories, and historical events. This effect is produced

through the layering of imagery and landscape photography such as the

transformation of Solomon Cocky Ngalyarrkiny sketches into unique animations,

or the collaging of historic photographs and maps. Keeping country is key to

these stories.

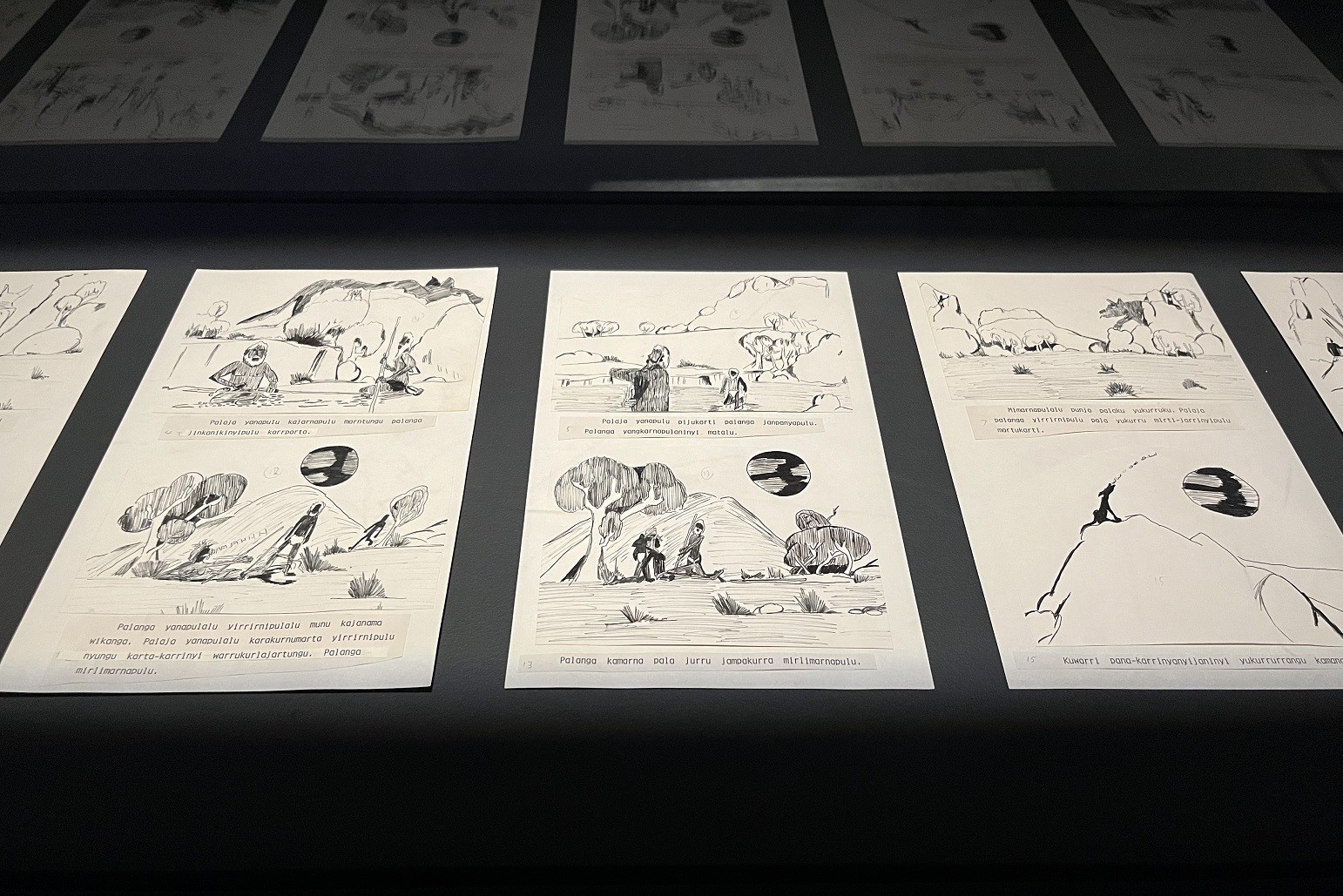

This show brings together different perspectives on Pilbara history through reflections on life during the strike and the resulting formation of the titular Strelley Mob, through works by key individuals such as Cocky Ngalyarrkiny and William Nyaparu Gardiner. The exhibition follows the experiences of the Strelley Mob during the 1946 Pilbara strike, which brought about the end of indentured labour in the north-west. Strelley Station was purchased some decades later by some of the “Strike Mob” with the assistance of unionist and communist Don McLeod. Nyangumarta is the lingua franca at Strelley station, with a focus on the celebration of language retention patent in the works. [3] There is even Nyangumarta signage for the exhibits, such as marnipirni for “illustrators” and yarntarna for “writers”, and in the audio tracks that form the soundscape of the gallery. The Strelley Mob established a bilingual school at Strelley Station, and a printing press, the Strelley Illustrated Literature Production Centre, which has produced hundreds of Nyangumarta language books. The Strelley Mob walk strong in both worlds, and their ambitions for self-determination are showcased throughout the exhibition. Their books dot the exhibition, but particularly cluster in the adjoining corridor. The prolific material of Cocky Ngalyarrkiny exemplifies both the variety and distinctive character of the exhibition, from his pujiman time plant collection in Bush Tucker, to the Station times massacre at Braeside, through to the strike period experiences such as The Shooting Dogs story. His unique and confident mode of illustration has an almost comic-like quality, a style which through his work with the Strelley Illustrated Literature Production Centre has come to exemplify both an idiom and a uniquely Aboriginal way of making books, in line with the goals of self-determination upon which Strelley Station was founded. [4]

Inclusions in this exhibition of artists such as Sam Fullbrook and James Wigley speak to the documentarians within the art scene at the time of the strike—drawn westwards to join various strike camps, and later Strelley—with both of these artists also embedding themselves within their host communities. Fullbrook and Wigley’s access to the everyday lives of the Strelley Mob appears to be facilitated by their time spent on country. Fullbrook, for example, based out of Pilangoora strike camp, would shoot kangaroos for mob to eat, or act as a legal representative for the group in disputes with the government. His Girl with Yandy is included in this exhibition, marked by his iconic colourist style, capturing the important role of the yandy as a symbol of the strike movement.[5] James Wigley ran the Strelley printing press and fell in with the community there, and went on to influence on the developing style of Nyaparu Gardiner as a fellow social realist.[6] Fullbrook was directly quoted by Gardiner as an influence in encouraging him to draw.[7] Other visiting artists include Allan Baker, whose sketches made during the 1950s and 1960s shared everyday life scenes from the camp, such as “The Reading Lesson” (circa 1980s)—which references literacy and numeracy classes run in the strike camps.

William Nyaparu Gardiner’s inclusions in the show speak to his earlier years growing up within the strike movement, with a series of sketches that act as a prelude to his painting style. This style is characterised by references to religious texts set against evocative landscapes and askew human figures. In his later life Gardiner would employ his memory to provide an insider’s perspective on the strike movement. Two examples of this body of work are included in the show, one a pencil sketch and the other a work in pencil, ink and acrylic, on the theme: Yandying. His broader themes and commentary speak to the slower and hungrier parts of the Strike movement, and the individuals within the itinerant labour force of this period.[8]

The film components of this exhibition feature the landscape characters that appear in the various Strelley press books exhibited in the show. Dreaming stories marked by landscape features as drawn by Cocky Ngalyarrkiny are reflected in Todorovic’s layering of materials, where Country remains integral to storytelling. Todorovic, a colleague of Jorgensen and Kral, uses film to explore people’s changing relationship with the environment (vimeo.com/tadar for examples), and this is on show in the films included in The Strelley Mob. These films are products of his work with the Nyangumarta and Strelley communities to retell these stories, undertaken in part out of the Illustrating Nyangumarta project. Two of these are dreaming stories, a family hunting memory for bush turkey, and The Convoy, which is based on a sit-down protest in 1980 in support of the Noonkanbah strike. The lives lived across this period of Pilbara history, and the many media that are used to mark and reflect these stories, invite the viewer into an important history—one that goes well beyond the Strike—as told by mob.

The Strelley Mob, John Curtin Gallery, 9 May - 8 Jul 2024.

Footnotes:

1. Stuart, D. (1959). Yandy. Georgian House.

2. Jorgensen, D. (2020). Slow Time: Nyaparu (William) Gardiner and the Strike Camps of the Pilbara. Journal of Australian Studies, 44(1), 82-96.

3. Ibid.

4. Kral, I., & Jorgensen, D. (2024b). The illustrated literature of Solomon Cocky: turning the Dreaming into books. World Art, 14(1), 27-47.

5. Jorgensen, D. (2020). Slow Time: Nyaparu (William) Gardiner and the Strike Camps of the Pilbara. Journal of Australian Studies, 44(1), 82-96.

6. Kral, I., & Jorgensen, D. (2024a). James Wigley and the Strelley Mob: Social Realist Painting in an Aboriginal Community. Journal of Australian Studies, 48(1), 17-32.

7. Jorgensen, D. (2020). Slow Time: Nyaparu (William) Gardiner and the Strike Camps of the Pilbara. Journal of Australian Studies, 44(1), 82-96.

8. Ibid.

Image credits: Installation photographs of The Strelley Mob at John Curtin Gallery provided by the author.

This show brings together different perspectives on Pilbara history through reflections on life during the strike and the resulting formation of the titular Strelley Mob, through works by key individuals such as Cocky Ngalyarrkiny and William Nyaparu Gardiner. The exhibition follows the experiences of the Strelley Mob during the 1946 Pilbara strike, which brought about the end of indentured labour in the north-west. Strelley Station was purchased some decades later by some of the “Strike Mob” with the assistance of unionist and communist Don McLeod. Nyangumarta is the lingua franca at Strelley station, with a focus on the celebration of language retention patent in the works. [3] There is even Nyangumarta signage for the exhibits, such as marnipirni for “illustrators” and yarntarna for “writers”, and in the audio tracks that form the soundscape of the gallery. The Strelley Mob established a bilingual school at Strelley Station, and a printing press, the Strelley Illustrated Literature Production Centre, which has produced hundreds of Nyangumarta language books. The Strelley Mob walk strong in both worlds, and their ambitions for self-determination are showcased throughout the exhibition. Their books dot the exhibition, but particularly cluster in the adjoining corridor. The prolific material of Cocky Ngalyarrkiny exemplifies both the variety and distinctive character of the exhibition, from his pujiman time plant collection in Bush Tucker, to the Station times massacre at Braeside, through to the strike period experiences such as The Shooting Dogs story. His unique and confident mode of illustration has an almost comic-like quality, a style which through his work with the Strelley Illustrated Literature Production Centre has come to exemplify both an idiom and a uniquely Aboriginal way of making books, in line with the goals of self-determination upon which Strelley Station was founded. [4]

Inclusions in this exhibition of artists such as Sam Fullbrook and James Wigley speak to the documentarians within the art scene at the time of the strike—drawn westwards to join various strike camps, and later Strelley—with both of these artists also embedding themselves within their host communities. Fullbrook and Wigley’s access to the everyday lives of the Strelley Mob appears to be facilitated by their time spent on country. Fullbrook, for example, based out of Pilangoora strike camp, would shoot kangaroos for mob to eat, or act as a legal representative for the group in disputes with the government. His Girl with Yandy is included in this exhibition, marked by his iconic colourist style, capturing the important role of the yandy as a symbol of the strike movement.[5] James Wigley ran the Strelley printing press and fell in with the community there, and went on to influence on the developing style of Nyaparu Gardiner as a fellow social realist.[6] Fullbrook was directly quoted by Gardiner as an influence in encouraging him to draw.[7] Other visiting artists include Allan Baker, whose sketches made during the 1950s and 1960s shared everyday life scenes from the camp, such as “The Reading Lesson” (circa 1980s)—which references literacy and numeracy classes run in the strike camps.

William Nyaparu Gardiner’s inclusions in the show speak to his earlier years growing up within the strike movement, with a series of sketches that act as a prelude to his painting style. This style is characterised by references to religious texts set against evocative landscapes and askew human figures. In his later life Gardiner would employ his memory to provide an insider’s perspective on the strike movement. Two examples of this body of work are included in the show, one a pencil sketch and the other a work in pencil, ink and acrylic, on the theme: Yandying. His broader themes and commentary speak to the slower and hungrier parts of the Strike movement, and the individuals within the itinerant labour force of this period.[8]

The film components of this exhibition feature the landscape characters that appear in the various Strelley press books exhibited in the show. Dreaming stories marked by landscape features as drawn by Cocky Ngalyarrkiny are reflected in Todorovic’s layering of materials, where Country remains integral to storytelling. Todorovic, a colleague of Jorgensen and Kral, uses film to explore people’s changing relationship with the environment (vimeo.com/tadar for examples), and this is on show in the films included in The Strelley Mob. These films are products of his work with the Nyangumarta and Strelley communities to retell these stories, undertaken in part out of the Illustrating Nyangumarta project. Two of these are dreaming stories, a family hunting memory for bush turkey, and The Convoy, which is based on a sit-down protest in 1980 in support of the Noonkanbah strike. The lives lived across this period of Pilbara history, and the many media that are used to mark and reflect these stories, invite the viewer into an important history—one that goes well beyond the Strike—as told by mob.

The Strelley Mob, John Curtin Gallery, 9 May - 8 Jul 2024.

Footnotes:

1. Stuart, D. (1959). Yandy. Georgian House.

2. Jorgensen, D. (2020). Slow Time: Nyaparu (William) Gardiner and the Strike Camps of the Pilbara. Journal of Australian Studies, 44(1), 82-96.

3. Ibid.

4. Kral, I., & Jorgensen, D. (2024b). The illustrated literature of Solomon Cocky: turning the Dreaming into books. World Art, 14(1), 27-47.

5. Jorgensen, D. (2020). Slow Time: Nyaparu (William) Gardiner and the Strike Camps of the Pilbara. Journal of Australian Studies, 44(1), 82-96.

6. Kral, I., & Jorgensen, D. (2024a). James Wigley and the Strelley Mob: Social Realist Painting in an Aboriginal Community. Journal of Australian Studies, 48(1), 17-32.

7. Jorgensen, D. (2020). Slow Time: Nyaparu (William) Gardiner and the Strike Camps of the Pilbara. Journal of Australian Studies, 44(1), 82-96.

8. Ibid.

Image credits: Installation photographs of The Strelley Mob at John Curtin Gallery provided by the author.