Not all art benefits from art criticism. Sometimes the personal, non-academic gain from art is far more valuable than any insight a piece of critical writing could provide. If you happened to see Helen Johnson’s solo-exhibition Follower, Leader at PICA earlier this year, the same thoughts might have crossed your mind. Johnson’s practice has all the desired qualities of technical achievement, idiosyncratic style, and conceptual depth, but the greatest intrigue of her most recent body of work is the inspiration she has taken from therapeutic art—a discipline that requires none of the above.

Distinct from the art that artworld enthusiasts are familiar with, therapeutic art rarely gains a mention in professional art circles (except in fractured ways); its tenure is to the psychoanalytic field rather than the visual arts field. Therapeutic art is rarely subjected to interpretation or aesthetic criticism as it is occupationally kept within the treatment room, rarely ever meeting a viewing public. Instead of seeking validation from an audience’s value-conferring aesthetic judgements, therapeutic art seeks to foster a deep respect for the autonomy a person has as the subject of their own experience. Whilst the non-therapeutic artworld has fashioned itself into a breeding ground for the sharing of personal stories, the insight into the personal achieved through the employment of art as therapeutic practice is encased by an impenetrable circle of trust that promises such art remains in the enclave of the private. Therapeutic art creates secure spaces to open avenues of reflection and discussion, but these conversations unfold in reach of the person who is seeking understanding, the art itself left residing beyond the spotlight.

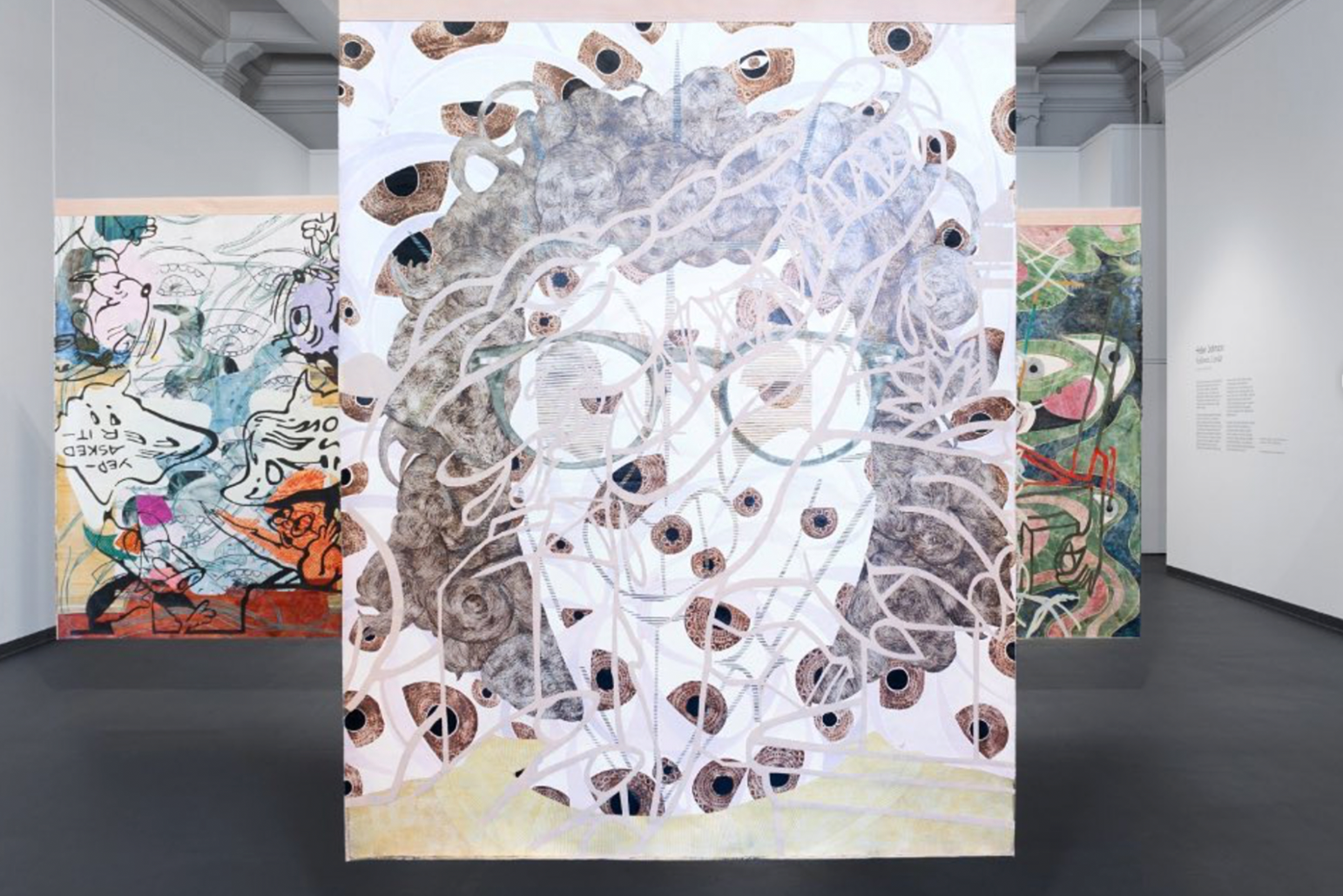

In bringing these ideas into the gallery space, Johnson inadvertently questions the entire practice of art viewership and (to my own dismay) complicates the role of art criticism. Whilst Johnson’s art is not an instance of therapeutic art and thus not beyond critical comment, her cross-disciplinary approach, spread between art therapy and contemporary practice, would make a forthright treatment of her work from the domain of the visual arts alone cheap and inexhaustive. The uncompromising, cryptic demeanour of Johnson’s paintings evidences the deeper engagement Johnson requires from her audience. Johnson’s paintings are expressive works that bungle abstract forms with figurative images to create a mumbo-jumbo of coarsely inhabited paintings. The use of stencils in the construction of each painted layer prohibits the cohesion of any one layer with another, resulting in seven finished paintings that look to be caught in internal struggles for space. The uncanny effect of these pieces is their fogginess —the figuration suggests narrative, but the imposition of untethered lines confuses the narrative, keeping the works retracted and incoherent. As in Debate, where an array of cartoon characters are squidged across the canvas, the nostalgic but distorted figures simultaneously allow a sense of familiarity whilst they strategically evade proper recognition. Knowable and unknowable, they are figures we’ve seen before but cannot confidently place. The additional uncanny pairs of eyes are rendered like the accompanying characters through the use of stencils, but are kept distinct through their stylistic ambiguity. The collision of images feeds into the push and pull between each layer, creating an irresolvable distortion of space. Such effects (which can be hitched to Johnson’s technical mastery of stencilling) express the complexity of the personal experiences that are often shared in art therapy sessions. Unlike traditional painting, where layers are dissolved to give way to a final image, Johnson’s layers remain on display, keenly ignorant of each other whilst ironically battling for inclusion—perhaps mirroring the struggle for coherent narratives sometimes enacted by patients of psychotherapy. As onlookers, we are prohibited from understanding the works in the way that the artist herself understands them. Of course, this could be said of almost all art, but what is unique is the disavowal of the spectator’s requirement to understand in this instance.

Not only does the technical construction of Johnson’s works place a divot between audience and painting in a turnabout recognition of the absences of audiences in art therapy, but Johnson’s body of work also creates avenues into the psychoanalytic field. Each work, styled around particular psychoanalytic theories and debates, created an exhibition that was as informative as it was visually stimulating. In Account authority, Johnson references a debate about the commonly used metaphor of pulling out weeds often employed to represent the eradication of unproductive thoughts. Weighing in with her agreement of Jacqueline Freeman’s alternative notion of metaphorically thinking of weeds as beneficial additions to deficient soil and as valuable markers for identifying spaces that require growth, Johnson’s didactic for the work is not only educational, but she is also providing an entryway into the long-stigmatised subject of psychotherapy. The works which otherwise evade any sort of deliberate interpretation from visual engagement alone instead put forward intriguing thoughts about mental well-being and the tools we use to maintain it.

Whilst the cross-disciplinary flair of Johnson’s work makes Follower, Leader an engaging and thought-provoking exhibition, Follower, Leader was somewhat let down by PICA’s undiscerning curation, which could have done more to speak to the nuances of Johnson’s paintings. The large works were each suspended from the ceiling in a tight arrangement, all facing the same direction. This display required a self-lead tour that, confusingly, needed to start from the back of the room. Many visitors entered from the front of the gallery, therefore seeing the backs of each of the paintings first, causing a disorientated viewing experience that resulted in a confusing first impression. Thinking back to the cosy setting PICA created for Wu Tsang’s Duilian (2023) and the resting places provided throughout the Joan Jonas exhibition that was being held downstairs concurrently to Johnson’s, it is a wonder the gallery did not put effort into making Follower, Leader a more welcoming and restful space, especially given the tone of Johnson’s art-therapy-inspired work.

What almost caused a bigger interpretive misfire was Follower, Leader’s untimely coalescence with the Perth Festival. To fasten a connection between the exhibition with this year’s theme of Ngaangk, the mother star or sun, there was a disproportionate emphasis on Johnson herself as a mother—which, despite being true and a subtle element in her work, was overexaggerated to create an awkward rejoinder between Ngaangk and the art therapy theme. A too strong and too exclusive emphasis on motherhood in an exhibition centred on art therapy comes dangerously close to feeding tropes of women as necessary caregivers—even risking the revival of the tired old characterisation of therapeutic art as an essentially feminine art. What saved the exhibition from this misdemeanour was the very minimal reference to motherhood in the works themselves, and the diverse treatment of the theme reinforced by didactics authored by the artist (leaving this almost-accident as the would-be-folly of insincere public planning).

Follower, Leader was a triumph for Johnson above anything else. She brought into the gallery a body of work that reaped the successful fruits of an art practice that bravely reaches beyond the closed box of contemporary art, towards art as it exists in another context. More so than simply taking art therapy as an inspiration for her work, Johnson’s exhibition showed painting reformatted at a fundamental level, a feat made possible by her expansive knowledge and understanding of the alternative role art serves in therapeutic settings. Whilst much of the success of Johnson’s work was left, at times, undermined by its unimaginative and lacklustre curation, it might be said that this is because not all art spaces (if any) are ready to alter their ways of working to make the most of cross-disciplinary or ‘outsider’ art practices. Thankfully for Johnson, her work is able to speak for itself.

Helen Johnson’s Follower, Leader was held at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 9 February - 31 March 2024.

Image credits: ‘Helen Johnson: Follow, Leader’, installation view, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), 2024. Photo: @artdoc_au

Distinct from the art that artworld enthusiasts are familiar with, therapeutic art rarely gains a mention in professional art circles (except in fractured ways); its tenure is to the psychoanalytic field rather than the visual arts field. Therapeutic art is rarely subjected to interpretation or aesthetic criticism as it is occupationally kept within the treatment room, rarely ever meeting a viewing public. Instead of seeking validation from an audience’s value-conferring aesthetic judgements, therapeutic art seeks to foster a deep respect for the autonomy a person has as the subject of their own experience. Whilst the non-therapeutic artworld has fashioned itself into a breeding ground for the sharing of personal stories, the insight into the personal achieved through the employment of art as therapeutic practice is encased by an impenetrable circle of trust that promises such art remains in the enclave of the private. Therapeutic art creates secure spaces to open avenues of reflection and discussion, but these conversations unfold in reach of the person who is seeking understanding, the art itself left residing beyond the spotlight.

In bringing these ideas into the gallery space, Johnson inadvertently questions the entire practice of art viewership and (to my own dismay) complicates the role of art criticism. Whilst Johnson’s art is not an instance of therapeutic art and thus not beyond critical comment, her cross-disciplinary approach, spread between art therapy and contemporary practice, would make a forthright treatment of her work from the domain of the visual arts alone cheap and inexhaustive. The uncompromising, cryptic demeanour of Johnson’s paintings evidences the deeper engagement Johnson requires from her audience. Johnson’s paintings are expressive works that bungle abstract forms with figurative images to create a mumbo-jumbo of coarsely inhabited paintings. The use of stencils in the construction of each painted layer prohibits the cohesion of any one layer with another, resulting in seven finished paintings that look to be caught in internal struggles for space. The uncanny effect of these pieces is their fogginess —the figuration suggests narrative, but the imposition of untethered lines confuses the narrative, keeping the works retracted and incoherent. As in Debate, where an array of cartoon characters are squidged across the canvas, the nostalgic but distorted figures simultaneously allow a sense of familiarity whilst they strategically evade proper recognition. Knowable and unknowable, they are figures we’ve seen before but cannot confidently place. The additional uncanny pairs of eyes are rendered like the accompanying characters through the use of stencils, but are kept distinct through their stylistic ambiguity. The collision of images feeds into the push and pull between each layer, creating an irresolvable distortion of space. Such effects (which can be hitched to Johnson’s technical mastery of stencilling) express the complexity of the personal experiences that are often shared in art therapy sessions. Unlike traditional painting, where layers are dissolved to give way to a final image, Johnson’s layers remain on display, keenly ignorant of each other whilst ironically battling for inclusion—perhaps mirroring the struggle for coherent narratives sometimes enacted by patients of psychotherapy. As onlookers, we are prohibited from understanding the works in the way that the artist herself understands them. Of course, this could be said of almost all art, but what is unique is the disavowal of the spectator’s requirement to understand in this instance.

Not only does the technical construction of Johnson’s works place a divot between audience and painting in a turnabout recognition of the absences of audiences in art therapy, but Johnson’s body of work also creates avenues into the psychoanalytic field. Each work, styled around particular psychoanalytic theories and debates, created an exhibition that was as informative as it was visually stimulating. In Account authority, Johnson references a debate about the commonly used metaphor of pulling out weeds often employed to represent the eradication of unproductive thoughts. Weighing in with her agreement of Jacqueline Freeman’s alternative notion of metaphorically thinking of weeds as beneficial additions to deficient soil and as valuable markers for identifying spaces that require growth, Johnson’s didactic for the work is not only educational, but she is also providing an entryway into the long-stigmatised subject of psychotherapy. The works which otherwise evade any sort of deliberate interpretation from visual engagement alone instead put forward intriguing thoughts about mental well-being and the tools we use to maintain it.

Whilst the cross-disciplinary flair of Johnson’s work makes Follower, Leader an engaging and thought-provoking exhibition, Follower, Leader was somewhat let down by PICA’s undiscerning curation, which could have done more to speak to the nuances of Johnson’s paintings. The large works were each suspended from the ceiling in a tight arrangement, all facing the same direction. This display required a self-lead tour that, confusingly, needed to start from the back of the room. Many visitors entered from the front of the gallery, therefore seeing the backs of each of the paintings first, causing a disorientated viewing experience that resulted in a confusing first impression. Thinking back to the cosy setting PICA created for Wu Tsang’s Duilian (2023) and the resting places provided throughout the Joan Jonas exhibition that was being held downstairs concurrently to Johnson’s, it is a wonder the gallery did not put effort into making Follower, Leader a more welcoming and restful space, especially given the tone of Johnson’s art-therapy-inspired work.

What almost caused a bigger interpretive misfire was Follower, Leader’s untimely coalescence with the Perth Festival. To fasten a connection between the exhibition with this year’s theme of Ngaangk, the mother star or sun, there was a disproportionate emphasis on Johnson herself as a mother—which, despite being true and a subtle element in her work, was overexaggerated to create an awkward rejoinder between Ngaangk and the art therapy theme. A too strong and too exclusive emphasis on motherhood in an exhibition centred on art therapy comes dangerously close to feeding tropes of women as necessary caregivers—even risking the revival of the tired old characterisation of therapeutic art as an essentially feminine art. What saved the exhibition from this misdemeanour was the very minimal reference to motherhood in the works themselves, and the diverse treatment of the theme reinforced by didactics authored by the artist (leaving this almost-accident as the would-be-folly of insincere public planning).

Follower, Leader was a triumph for Johnson above anything else. She brought into the gallery a body of work that reaped the successful fruits of an art practice that bravely reaches beyond the closed box of contemporary art, towards art as it exists in another context. More so than simply taking art therapy as an inspiration for her work, Johnson’s exhibition showed painting reformatted at a fundamental level, a feat made possible by her expansive knowledge and understanding of the alternative role art serves in therapeutic settings. Whilst much of the success of Johnson’s work was left, at times, undermined by its unimaginative and lacklustre curation, it might be said that this is because not all art spaces (if any) are ready to alter their ways of working to make the most of cross-disciplinary or ‘outsider’ art practices. Thankfully for Johnson, her work is able to speak for itself.

Helen Johnson’s Follower, Leader was held at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, 9 February - 31 March 2024.

Image credits: ‘Helen Johnson: Follow, Leader’, installation view, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), 2024. Photo: @artdoc_au