Despite the fact of their very well-established material relationship, myth and art history—by their very definitions—seem antithetical. Myth is invented, suggesting the unfounded or false. Its frequent synonym, legend, is of the same root as legible, a morpheme encapsulating the idea being that the written word can transmute history into fact, the past into truth. Consider a map, whose “legend” is a code that offers explanations for a map’s abstract signs and symbols. It is the job of pesky art historians to add time and historicization to ‘decode’ such texts. Whither visual art in this foggy set of ideas? A recent exhibition of works by painter Susan Ecker at the small Orangery Gallery in Shenton Park was certainly not where I expected to find any answers.

I found myself confronting these ideas in front of a selection of Susan Ecker’s drawings, paintings, prints, and mixed media works at the Orangery. The exhibition, Players, Places: Reprised, Renewed, does not dispel the fraught hazes of myth, symbol, and legend, but rather offers us a way of moving through them. Taking art, art histories, and lived experience as her subjects, Ecker reinterprets and repositions them against known narratives. Ecker’s set of characters—players, if you will—are the touchstones offering us concrete meanings.

Some of the key subjects that appear and repeat throughout Ecker’s iconography are Daphne, horses, Virgil, cows, art museums, goddesses, Lady Godiva, and roads. Those familiar with stories of the Greeks, Romans, and Anglo-Saxons will already recognise the potent themes that stem from these subjects: moments of transformation; struggles for power and ambition; liminal or transitory spaces; the contested site/sight of the female body; the acts of looking, reading, seeing. Ecker, a native New Yorker who mostly lives in the rural south west of WA, adds a distinct Australian-ness to her landscape works, a handful of which feature in this mostly-figurative exhibition. Anyone who has lived down south will know that a road is very different to a street—only the latter leads to museums, galleries, art institutions. But I am getting ahead of myself. First, the Greeks.

The story of Daphne and Apollo is one of resistance: Daphne, either a mortal or nymph woman, is the object d’affectionof Apollo, male god of poetry and light. Unfortunately, for any romantics reading, Daphne did not love Apollo back, and in protest against his persistent and unwanted advances she transformed herself into a laurel tree. Written versions of the story exaggerate different aspects (Apollo’s chase, Daphne’s refusal) but most visual depictions focus on Daphne’s moment of transformation—including Ecker’s drawing and Bernini’s famed sculpture (more on that Renaissance work shortly). In Daphne Entwined, Ecker’s drawing is loose, gestural, “in process” as much as Daphne is in process, beginning her moment of transforming. The surface washes (the work is charcoal on prepared canvas) give a delicate quality, offset by deliberate mark-making, both controlled and evocative. Daphne’s face just makes it into the top of the composition. Her arms are raised above her head in a pose resembling the T-shape of Christ’s crucifixion, alluding to the idea of sacrifice: in Ecker’s drawing, she is more martyr than naiad. The other famous T-shape/iconography within art history is of course the Vitruvian man by Leonardo Da Vinci—but here the outstretched pose is not a symbol of man/science/history, rather woman/nature/myth.

Back to Bernini: the 17th century artist is credited with the most famous artistic rendition of Daphne, in a late Renaissance/Baroque marble sculpture at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. Having seen the sculpture in its grandiose location, it is impossible to dispute Bernini's mastery of making marble appear as flesh. In Googling that sculpture, the first image result is a detail of Apollo’s hand grasping at the soft ‘flesh’ of Daphne’s waist, his finger indents subtly curving the marble.

Ecker’s renditions of Daphne (there are three in the exhibition) are equally compelling, but for very different reasons. One is their materiality: Ecker works with charcoal. Forgetting that charcoal is known for being cheap, messy, and easily accessible to artists, and that Ecker is a ‘contemporary woman artist’ whilst Bernini is a ‘Renaissance man artist’, the crucial difference here is this choice of medium. Charcoal—charred twigs of willow or vine—is as intimate to its subject as the viewer is with these three-quarter depictions of Daphne. The connotation of charcoal being the favoured material for the modest preparatory sketch is eviscerated by Ecker’s masterful handling of the material. To further a feminist reading, one might consider how Bernini has chiselled out his marble Daphne—carving, subtracting, removing—whilst Ecker has drawn in her subject; adding, suggesting, transmitting. Ecker’s 74.7 x 59.5 cm retelling conveys the flurry of the story’s climax through whooshing lines and ghostly smears—leaves borne upwards on the air as her transformation takes hold. In this way, one might be tempted to suggest that Ecker’s is a more realistic depiction than Bernini’s life-size statue. For Bernini, the drama is melodrama, all stricken poses (Daphne’s wide-open mouth, her frozen and wooded hair, the line of Apollo’s piercing gaze redirecting us to the tense scenario). Ecker’s is a visual drama—the becoming, enveloping, gesturing, the pivotal moment for Daphne herself.

Ecker also paints/draws (a distinction she blurs throughout the exhibition) Daphne Enwrapped and Daphne Changing. In the latter work, we see her expression: eyes closed, mouth open, her face a death mask of sorts, as she begins a new life in the laurel tree. The organic forms grow like a cage around her—not to keep her in, but to keep her pursuer out. This work has a heavy darkness in the charcoal marks, more urgent than her Entwined, communicating the gravitas of the narrative. In Daphne Enwrapped she is no longer naked, and a slight serene smile plays about her mouth. Ecker has drawn Daphne’s own hand disappearing into foliage. Now there’s a thought—here, the impossible choice of Daphne becoming the laurel tree to avoid the grasp of a man becomes an allegory for painting: the shapeshifting in between-ness of a subject represented through paint, at once present and out of reach, neither “hand” nor “foliage”, as we describe, but really the arrangement of marks on a surface.

In Godiva: Coventry Ride, Ecker depicts the 13th century legend, perhaps known more commonly today by the fleeting reference in the Queen song (or by Velvet Underground for the true fans). Lady Godiva is another story about womanhood—and interestingly for a painter, it is a story about looking. This story is repeated in material and visual culture throughout history, in various paintings, coins, sculptures, and a permanent exhibition in the English town of Coventry.

The impossible choice here was not death but shame. Lady G, wife of an Earl, was forced to ride through the streets naked, a challenge she accepted at the threat/incentive of her husband (who had refused to cease a heavy tax on the starving townspeople despite her pleading) . The story goes that Lady Godiva accepted the insulting proposal to ride naked through the streets, ordered the citizens indoors, and used her long hair to cover herself. One version of the legend is where the phrase “Peeping Tom” allegedly originates: the man who couldn’t help himself was blinded (or killed in some versions) for his transgression. “His eyes, before they had their will, / Were shrivel'd into darkness in his head,” so saith poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Ecker’s painting depicts not Lady Godiva’s nude pose, voluptuous form, or hurried dash, but Lady Godiva in a moment of quiet commune with her trusty steed. The horse faces towards her figure, instead of charging ahead. Beginning, or ending, her journey, this moment of true communication, trust, companionship, is not the usual artistic choice (by usually male artists), which prefers her static in the ride, her body poised and on display. Like the laurel tree-become-cage, Lady Godiva’s hair is a symbol of her femininity, thus her vulnerability, and her protective shield, thus her defence. I’m reminded of that fantastic quote from Fleabag: “Hair is everything. We wish it wasn’t so we could actually think about something else occasionally. But it is. It’s the difference between a good day and a bad day. We’re meant to think that it’s a symbol of power, that it’s a symbol of fertility. Some people are exploited for it and it pays your fucking bills. Hair is everything.”

Depictions of horses continue in Ecker’s Figures & Horse: West Frieze – Parthenon, and Horse: West Frieze – Parthenon. Horses are complex and social mammals. Domesticated for use in war, sport, and (most recently) therapy. In contemporary city life they are most commonly encountered, strangely, as police transport. Symbolically they are creatures of strength and independence. The Parthenon Frieze depicts the grandiose behaviours of horses—rearing, whinnying, wearing armour—that embody these associations. Ecker further explores the Parthenon sculptures in Figures: East Frieze – Parthenon, Three Figures: Parthenon Pediment, and Heifers: Parthenon – East Frieze. These works appear gentle, delicate and subtle on their surface, but through the repetition of subject it is clear Ecker does not shy away from ideas and debates about access, beauty, and ownership.

There is a knowingness here, a life spent looking—at artworks in museums, in galleries, in studios. The result is, frankly, a distillation of so much visual noise into coherent and compelling moments. The images are highly resolved, but that is not to say they are static, lifeless or boring. Ecker’s undulating compositions constantly remind us that we are looking, too. To paraphrase the art historian Griselda Pollock, Ecker’s works, taken both individually and as a whole exhibition, shift accepted meanings and undo cultural fixities. Undeniably there is a contemporary feminist logic to producing these works, as much as feminism is a reading strategy available to us to look at them.

Susan Ecker’s Players, Places: Reprised, Renewed runs until Sunday 7 April at The Orangery Gallery, 320 Onslow Road, Shenton Park.

Image credits:

Susan Ecker, Three Figures: Parthenon Pediment, mixed media on prepared paper, 63 x 80 cm.

Susan Ecker, Daphne Changing, charcoal on prepared canvas, 63 x 63 cm.

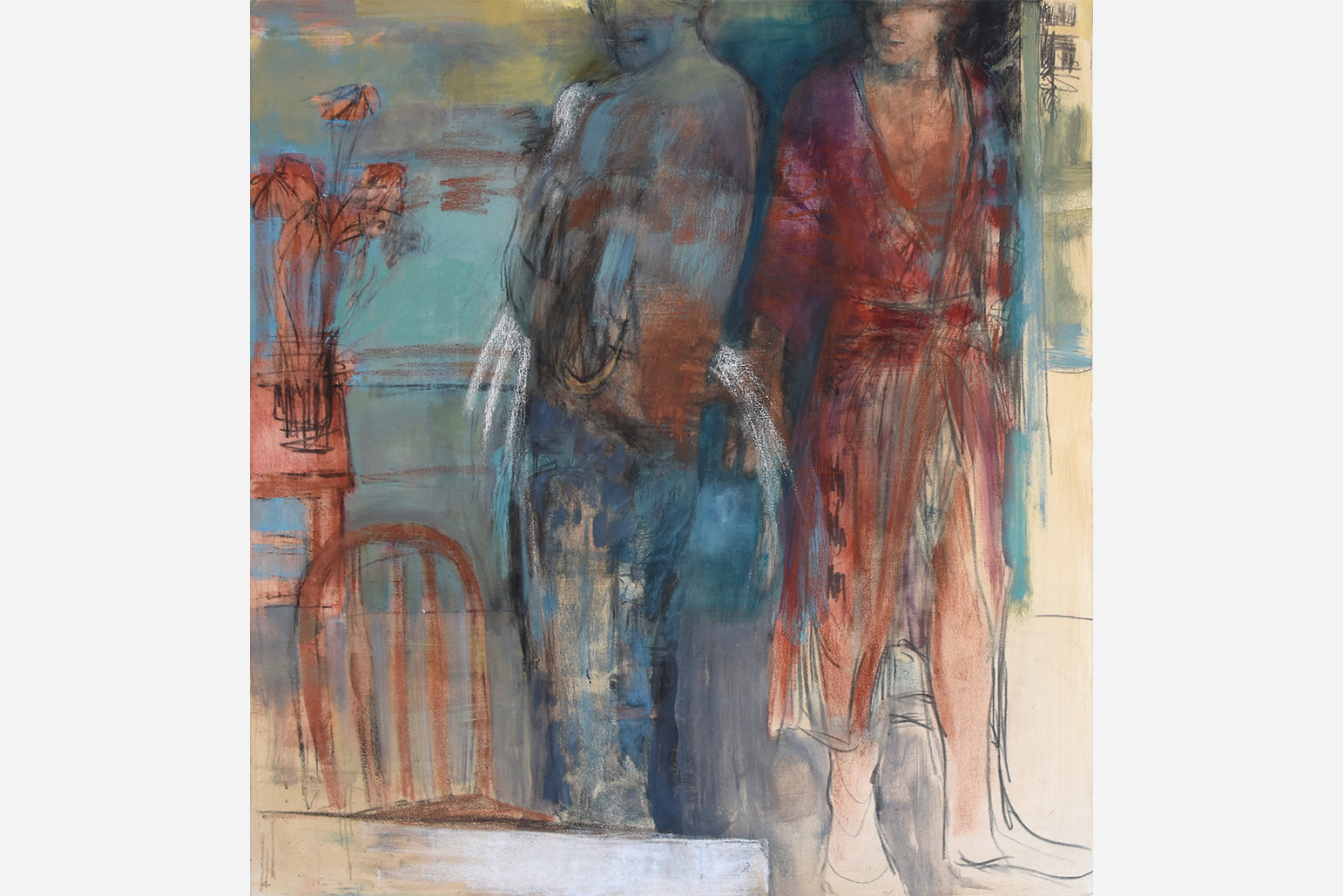

Susan Ecker, Players: Red – Blue, mixed media/oil on canvas, 129.5 x 121.5 cm.

I found myself confronting these ideas in front of a selection of Susan Ecker’s drawings, paintings, prints, and mixed media works at the Orangery. The exhibition, Players, Places: Reprised, Renewed, does not dispel the fraught hazes of myth, symbol, and legend, but rather offers us a way of moving through them. Taking art, art histories, and lived experience as her subjects, Ecker reinterprets and repositions them against known narratives. Ecker’s set of characters—players, if you will—are the touchstones offering us concrete meanings.

Some of the key subjects that appear and repeat throughout Ecker’s iconography are Daphne, horses, Virgil, cows, art museums, goddesses, Lady Godiva, and roads. Those familiar with stories of the Greeks, Romans, and Anglo-Saxons will already recognise the potent themes that stem from these subjects: moments of transformation; struggles for power and ambition; liminal or transitory spaces; the contested site/sight of the female body; the acts of looking, reading, seeing. Ecker, a native New Yorker who mostly lives in the rural south west of WA, adds a distinct Australian-ness to her landscape works, a handful of which feature in this mostly-figurative exhibition. Anyone who has lived down south will know that a road is very different to a street—only the latter leads to museums, galleries, art institutions. But I am getting ahead of myself. First, the Greeks.

The story of Daphne and Apollo is one of resistance: Daphne, either a mortal or nymph woman, is the object d’affectionof Apollo, male god of poetry and light. Unfortunately, for any romantics reading, Daphne did not love Apollo back, and in protest against his persistent and unwanted advances she transformed herself into a laurel tree. Written versions of the story exaggerate different aspects (Apollo’s chase, Daphne’s refusal) but most visual depictions focus on Daphne’s moment of transformation—including Ecker’s drawing and Bernini’s famed sculpture (more on that Renaissance work shortly). In Daphne Entwined, Ecker’s drawing is loose, gestural, “in process” as much as Daphne is in process, beginning her moment of transforming. The surface washes (the work is charcoal on prepared canvas) give a delicate quality, offset by deliberate mark-making, both controlled and evocative. Daphne’s face just makes it into the top of the composition. Her arms are raised above her head in a pose resembling the T-shape of Christ’s crucifixion, alluding to the idea of sacrifice: in Ecker’s drawing, she is more martyr than naiad. The other famous T-shape/iconography within art history is of course the Vitruvian man by Leonardo Da Vinci—but here the outstretched pose is not a symbol of man/science/history, rather woman/nature/myth.

Back to Bernini: the 17th century artist is credited with the most famous artistic rendition of Daphne, in a late Renaissance/Baroque marble sculpture at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. Having seen the sculpture in its grandiose location, it is impossible to dispute Bernini's mastery of making marble appear as flesh. In Googling that sculpture, the first image result is a detail of Apollo’s hand grasping at the soft ‘flesh’ of Daphne’s waist, his finger indents subtly curving the marble.

Ecker’s renditions of Daphne (there are three in the exhibition) are equally compelling, but for very different reasons. One is their materiality: Ecker works with charcoal. Forgetting that charcoal is known for being cheap, messy, and easily accessible to artists, and that Ecker is a ‘contemporary woman artist’ whilst Bernini is a ‘Renaissance man artist’, the crucial difference here is this choice of medium. Charcoal—charred twigs of willow or vine—is as intimate to its subject as the viewer is with these three-quarter depictions of Daphne. The connotation of charcoal being the favoured material for the modest preparatory sketch is eviscerated by Ecker’s masterful handling of the material. To further a feminist reading, one might consider how Bernini has chiselled out his marble Daphne—carving, subtracting, removing—whilst Ecker has drawn in her subject; adding, suggesting, transmitting. Ecker’s 74.7 x 59.5 cm retelling conveys the flurry of the story’s climax through whooshing lines and ghostly smears—leaves borne upwards on the air as her transformation takes hold. In this way, one might be tempted to suggest that Ecker’s is a more realistic depiction than Bernini’s life-size statue. For Bernini, the drama is melodrama, all stricken poses (Daphne’s wide-open mouth, her frozen and wooded hair, the line of Apollo’s piercing gaze redirecting us to the tense scenario). Ecker’s is a visual drama—the becoming, enveloping, gesturing, the pivotal moment for Daphne herself.

Ecker also paints/draws (a distinction she blurs throughout the exhibition) Daphne Enwrapped and Daphne Changing. In the latter work, we see her expression: eyes closed, mouth open, her face a death mask of sorts, as she begins a new life in the laurel tree. The organic forms grow like a cage around her—not to keep her in, but to keep her pursuer out. This work has a heavy darkness in the charcoal marks, more urgent than her Entwined, communicating the gravitas of the narrative. In Daphne Enwrapped she is no longer naked, and a slight serene smile plays about her mouth. Ecker has drawn Daphne’s own hand disappearing into foliage. Now there’s a thought—here, the impossible choice of Daphne becoming the laurel tree to avoid the grasp of a man becomes an allegory for painting: the shapeshifting in between-ness of a subject represented through paint, at once present and out of reach, neither “hand” nor “foliage”, as we describe, but really the arrangement of marks on a surface.

In Godiva: Coventry Ride, Ecker depicts the 13th century legend, perhaps known more commonly today by the fleeting reference in the Queen song (or by Velvet Underground for the true fans). Lady Godiva is another story about womanhood—and interestingly for a painter, it is a story about looking. This story is repeated in material and visual culture throughout history, in various paintings, coins, sculptures, and a permanent exhibition in the English town of Coventry.

The impossible choice here was not death but shame. Lady G, wife of an Earl, was forced to ride through the streets naked, a challenge she accepted at the threat/incentive of her husband (who had refused to cease a heavy tax on the starving townspeople despite her pleading) . The story goes that Lady Godiva accepted the insulting proposal to ride naked through the streets, ordered the citizens indoors, and used her long hair to cover herself. One version of the legend is where the phrase “Peeping Tom” allegedly originates: the man who couldn’t help himself was blinded (or killed in some versions) for his transgression. “His eyes, before they had their will, / Were shrivel'd into darkness in his head,” so saith poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Ecker’s painting depicts not Lady Godiva’s nude pose, voluptuous form, or hurried dash, but Lady Godiva in a moment of quiet commune with her trusty steed. The horse faces towards her figure, instead of charging ahead. Beginning, or ending, her journey, this moment of true communication, trust, companionship, is not the usual artistic choice (by usually male artists), which prefers her static in the ride, her body poised and on display. Like the laurel tree-become-cage, Lady Godiva’s hair is a symbol of her femininity, thus her vulnerability, and her protective shield, thus her defence. I’m reminded of that fantastic quote from Fleabag: “Hair is everything. We wish it wasn’t so we could actually think about something else occasionally. But it is. It’s the difference between a good day and a bad day. We’re meant to think that it’s a symbol of power, that it’s a symbol of fertility. Some people are exploited for it and it pays your fucking bills. Hair is everything.”

Depictions of horses continue in Ecker’s Figures & Horse: West Frieze – Parthenon, and Horse: West Frieze – Parthenon. Horses are complex and social mammals. Domesticated for use in war, sport, and (most recently) therapy. In contemporary city life they are most commonly encountered, strangely, as police transport. Symbolically they are creatures of strength and independence. The Parthenon Frieze depicts the grandiose behaviours of horses—rearing, whinnying, wearing armour—that embody these associations. Ecker further explores the Parthenon sculptures in Figures: East Frieze – Parthenon, Three Figures: Parthenon Pediment, and Heifers: Parthenon – East Frieze. These works appear gentle, delicate and subtle on their surface, but through the repetition of subject it is clear Ecker does not shy away from ideas and debates about access, beauty, and ownership.

There is a knowingness here, a life spent looking—at artworks in museums, in galleries, in studios. The result is, frankly, a distillation of so much visual noise into coherent and compelling moments. The images are highly resolved, but that is not to say they are static, lifeless or boring. Ecker’s undulating compositions constantly remind us that we are looking, too. To paraphrase the art historian Griselda Pollock, Ecker’s works, taken both individually and as a whole exhibition, shift accepted meanings and undo cultural fixities. Undeniably there is a contemporary feminist logic to producing these works, as much as feminism is a reading strategy available to us to look at them.

Susan Ecker’s Players, Places: Reprised, Renewed runs until Sunday 7 April at The Orangery Gallery, 320 Onslow Road, Shenton Park.

Image credits:

Susan Ecker, Three Figures: Parthenon Pediment, mixed media on prepared paper, 63 x 80 cm.

Susan Ecker, Daphne Changing, charcoal on prepared canvas, 63 x 63 cm.

Susan Ecker, Players: Red – Blue, mixed media/oil on canvas, 129.5 x 121.5 cm.