Ceramically Speaking: Wonky pottery, Post-millennial pottery, and Weed Craft 2.0

Saturday, 20 July 2024

Introduction

How do trends in art emerge? According to John Roberts, aesthetic movements follow a process of negation where skills that have become ‘bloated with cultural capital’ are subsequently rejected, replaced or botched. If we look at the modern art timeline and blur our eyes, we can see each successive movement as a rejection of what had come before. Realism sucks, paint crazy. Crazy paint sucks, show a blank canvas. Canvas sucks, just have a chair. Chairs suck, just write a word. Writing sucks, just dance. Ad infinitum? Consensus goes that the great project of stripping-back ended in the 80s when Danto saw Warhol’s Brillo box and said, ‘well, that’s it. It’s all been done. It’s the end of art.’[1] Everyone agreed, probably because they were sick of getting confused. After a century of deskilling and throwing the old tools away, had artists arrived at their final utopian art form? For Adorno, an aesthetic end-point is impossible: ‘The moment a limit is posited, it is overstepped, and that against which the limit was established is absorbed’. With time and popularity, the radical becomes water.

While the subsequent epochs lacked the downhill running-race logic of modernism, today’s aesthetic trends are just as reactionary. Artists deskill and reskill as times necessitate. The process of negation not only applies to capital-a Art, but all aspects of visual culture. My interest today is in pottery. Specifically, three recent aesthetic styles that have arisen during the crockery boom of the last ten years: wonky pottery, post-millennial pottery, and Weed Craft; each a reaction against the surrounding culture, and each aestheticising a different kind of amateurism.

Why have pottery classes become so popular? After the Arts and Crafts revival of the 1970s, demand for hand-made ceramics all but died. Art schools closed their studios, pawned their kilns, and for years pottery was relegated to the hobby of your daggy aunt. Now, it’s been dubbed ‘the new yoga’ and everyone from all your friends to Seth Rogen are making cool stuff out of clay. We can credit the revived interest in ceramics to the popularity of one aesthetic in the mid 2010s: wonky pottery, whose light and cheerful amateurism gave a wholesome millennial facelift to the earthy ergonomic austerity previously associated with ceramics.

But where do we go when amateurism becomes the new normal, not found just in markets and Etsy but K-Marts everywhere? Instead of chucking a u-ey and re-embracing functional sleekness, the aesthetics of post-millennial pottery and Weed Craft further double down on amateurism as a rejection of wonky pottery’s easily commodified and mass-produced cuteness. Weed Craft, however innocently, uses amateurism to weaponize irony, humour and meaninglessness against the cultural turn towards sincerity and performed vulnerability. The style aligns itself with the ‘radical stupidity’ aesthetic of memes, Adult Swim, and teen boys everywhere. Perhaps less ideologically reactionary but more of a formal contrast is the aesthetic of post-millennial pottery, which pushes the limits of amateurism towards maximalism, ugliness, and chaos. While wonky pottery, Weed Craft and post-millennial pottery began as radical changes from the status quo, their styles became ubiquitous and predictable enough to call for further unnamed movements.

Wonky pottery, millennial aesthetics and the cute

When Vogue referred to pottery as ‘the new yoga’ in 2017, it was indicative of a cultural turn towards self-care and wellness during the instability of the late 2010s, heightened to further extremes during the pandemic. Pottery, framed not just as an art form but a lifestyle choice, offers the appealing promise of having something slow, methodical and physical to do with your hands on a Tuesday night. Like the children's pastime of colouring in, ceramics has come to be reframed as a meditative practice.[2] While the end goal is still to make something functional and/or decorative while improving your skills, the technical skill and beauty of the finished product is seen as secondary to the process. With the ‘your-best-is-okay’ mentality of extra-curricular workshops, and the ever-increasing ability (and expectation) to share any act of creation online to the masses, a particular aesthetic of amateurism emerges.

For several years, one could enter any gallery gift-shop, craft market or middlebrow homeware store and find a range of minimalistic, slightly mis-shapen and blob-like mugs and planters in combinations of white and pastel colours. This ‘light and fun’ aesthetic was a sharp contrast from the earthy browns, visual heaviness and general symmetry previously associated with the artform. This pottery is quirky and funky and you gotta have it.

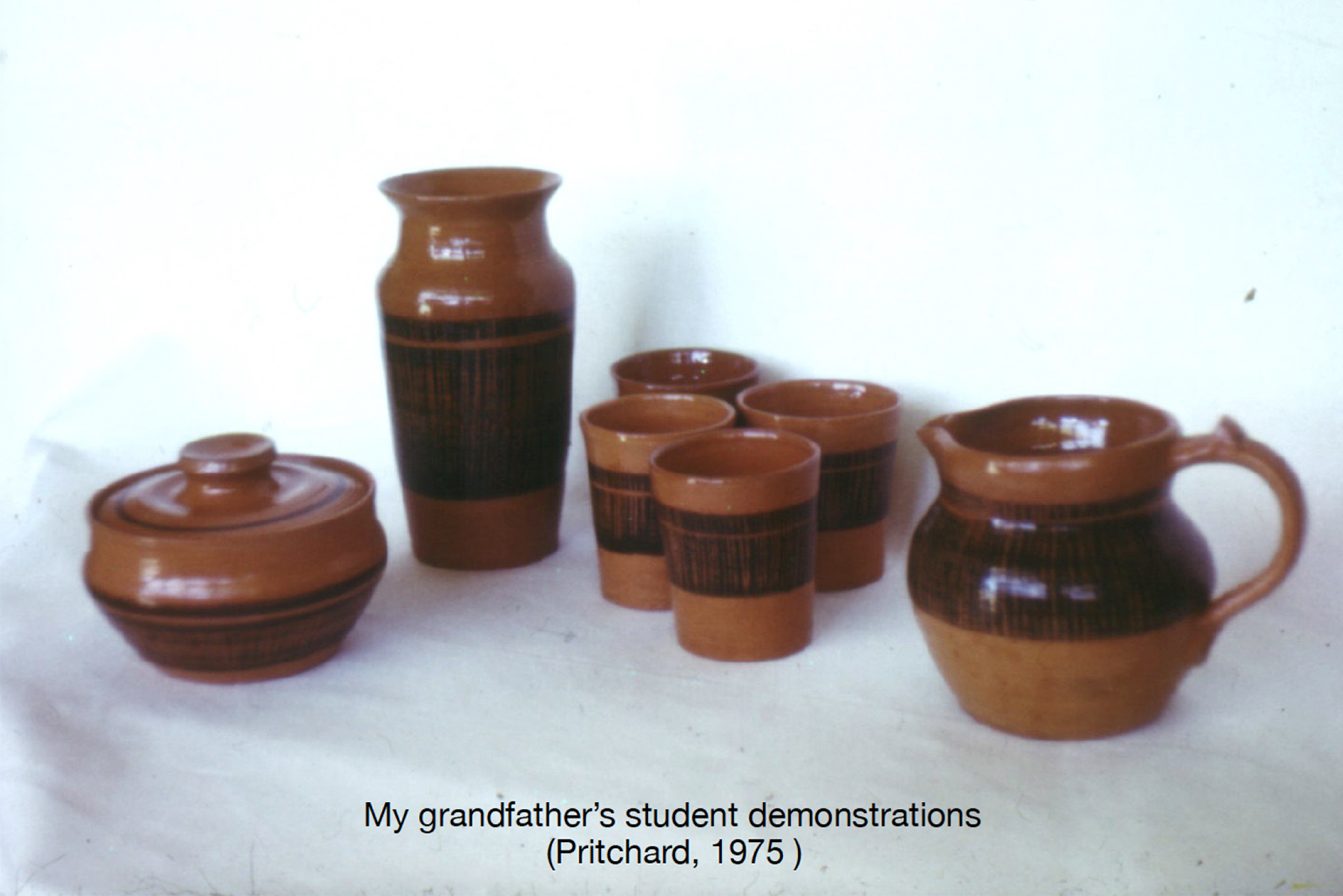

My grandfather Leon Pritchard taught ceramics in Perth from the mid-60s to early-80s and noted there was a similar market desire for ‘back to nature’ homemade wares.[3] [4] The key principle my grandpa taught was ‘form follows function’; technical skill and ergonomic design were the potter’s first priority. The criteria for making something ‘good enough to give away’ was, more-or-less, prescriptive. Unsurprisingly, my grandpa was not a fan of the wonky pottery popular today, likening it to ‘aviomorphic excrement’. This isn’t to say that ceramic artists weren’t doing creative, experimental or whimsical things during the Craft boom—lot of my grandpa’s work was funny and playful, but still had an austere quality. In order for ceramics to regain popularity with modern audiences, older ideals of skill and beauty had to be updated.

Wonky pottery has become inseparable from the Corporate Memphis-inspired ‘millennial aesthetic’, whose main domains are infographics, flat-illustrations, interior design, and anything rose-gold.[5] While millennial aesthetics seem innocent in their calming visuals, diverse representations, and general whimsy, they are also the chosen aesthetics of hegemonic tech companies (excluding the gamer-keyboard stylings of the Muskiverse). One way of understanding the enduring appeal of millennial aesthetics is through Sienne Ngai’s theory of the cute, which she equates to the “aestheticization of powerlessness.”[6] Cute is generally used to describe things that are small, weak, simple in form, infantile, feminine, and unthreatening. Extreme cuteness invites us to react in turn with infantile adoration: curling up, doing a baby voice and mushmouthing our words. Small becomes smol, haha becomes hehe, and every Subject becomes ‘just a little guy.’[7] Most importantly, the cute desires to be held and acquired, “to want us and only us to be its mommy.” In other words, cuteness is an ingeniously marketable aesthetic for selling commodities.

Yet cuteness often has the opposite effect of repellance, being employed so obviously to manipulate our sympathies—think of when the spanish cat makes the big eyes in Shrek 2. According to Harris, objects are cutest when ‘maimed and hobbled’, often straddling the line into the grotesque. The wonkiness of wonky pottery is undeniably ‘cute’, and so are Google’s ubiquitous bean people with their disproportionate limbs; but they are not too cute. Rarely do we notice the manipulation until someone points it out. The subtle cuteness of millennial aesthetics have so easily become the default, a weighted blanket of pleasantry and calmness. Is this a bad thing? To be openly hateful or dismissive of cuteness, of its associations with femininity, care and vulnerability, will cast doubts on the quality of one’s character. The cute often doesn’t want to be critiqued or questioned, just adored or ignored.

Weed Craft 2.0, irony and radical stupidity

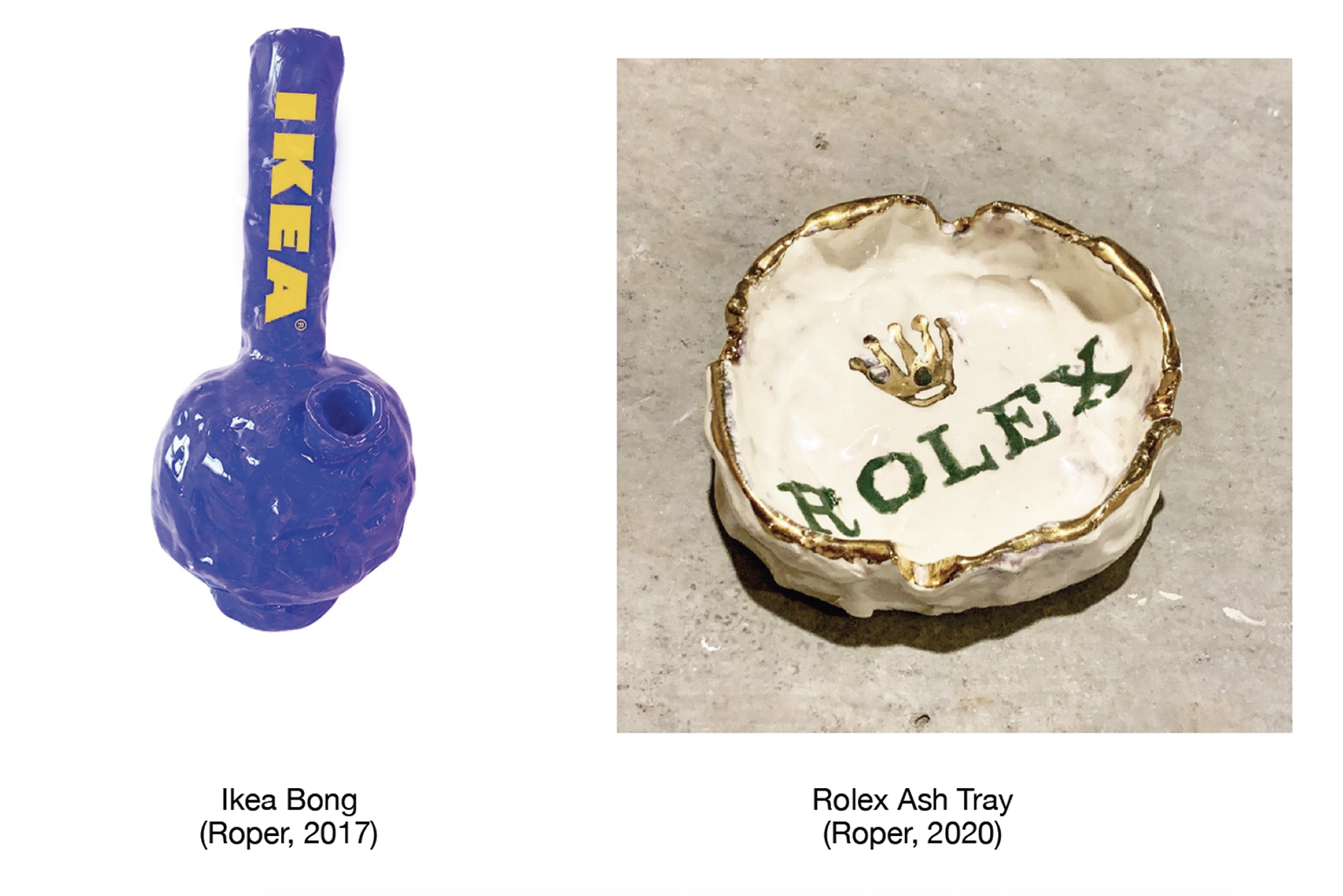

Parallel, and perhaps counter, to the inoffensiveness of wonky pottery rose the irony—laden ceramic movement of ‘Weed Craft’, coined by artist Dean Roper in 2012. Like many internet spawned aesthetic genres, it is doubtful that Weed Craft was meant to be anything other than a dumb and meaningless name, like chillwave or seapunk; yet the Weed Craft Tumblr and Instagram pages show a clear aesthetic sensibility spread across ceramic artists from round the world, making pottery that is neither traditionally skilled, tasteful, cute or immediately sincere. Roper’s own work—badly rendered IKEA bongs, ceramic Cheetos, and Rolex ash trays—follow the ‘so dumb it's great’ logic of what Nicolas Holm labels 'radical stupidity’.[8]

Holm traces this style of contemporary humour to the rise of Adult Swim in the early 2000s, a block on Cartoon Network that showcased original cartoons that were all aesthetically ugly, cheaply produced, seemingly incoherent, and heavily appropriated the detritus of popular culture. While shows like Space Ghost, Aqua Teen Hunger Force and Tim & Eric were groundbreaking at the time, breaking the established setup/punchline formula of the joke, Holm argues that radical stupidity is now unquestionably the internet’s dominant style of humour. From the nonsensical and crude aesthetics of memes, to the glitchy editing of TikTok videos, and most unpleasantly, the maxed-out irony and nihilism of 4chan and the alt-right… has the comedic freedom of radical stupidity actually freed us? While the radically stupid aesthetics of Weed Craft subvert the traditional skill, beauty and seriousness of ‘old white dude ceramics’,[9]and seem to be an alternative to the unfunniness of wonky pottery, they can also come off as obvious, serving up more of the same kind of humour we have come to expect. Even Roper admits that Weed Craft may have smirked itself into a corner: ‘I see the same shit being copied and posted on Instagram and Etsy and it makes me sick lol. So here is weed craft 2.0 for the real ass people out there.’ It is unclear whether 2.0 differs in any way from Weed Craft vanilla, or if the confession was also a half-ironic joke. This is the problem that every naughty boy artist, myself included, must face. To discuss your real problems openly is to be self-important and cringe, but if you do it with a bad Garfield drawing and a mirthless laugh, people will at least be laughing with you, right? Irony is both the paintbrush and the prison bars for every naughty boy.

Post-millennial pottery and ugliness

The embrace of ugliness as an expressive form—of clashing colours, jarring textures and whatever achieves disharmony, is the most recent ceramic trend I’ll discuss, and is most noticeably tied to subcultural fashion and y2k-revival web-design. Peter Hohendahl describes ugliness as a ‘result of techniques that refuse the final return from dissonance to consonance’.[10] If consonance or harmony is seen by most as a necessary quality of not just beauty, but agreeable taste and good art, then surely doing the opposite is a subversive act, right? In 2022, Side Gallery in Barcelona held the show Exposed Materials, gathering works from several contemporary artists whose pottery sought to push the limits of disharmony, ugliness, and chaos. Alex Knoche and Virginia Leonard’s pieces in the show looked so visually and texturally overwhelming they were said to provoke anxiety. Bearing only the slightest resemblance to functional homeware, the traditional ‘form follows function’ principles of ceramics are reversed, yet still we can recognise them as cups or vases in the medium’s tradition.

The botching involved in these works make Weed Craft and wonky pottery look conservative, yet skill is by no means abandoned, but employed strategically. Techniques deemed boring are negated and botched, yet techniques deemed necessary or desirable are continued and strengthened.[11] The chaotic shapes and colours may seem radical compared to traditional pottery, but the processes are nothing new and still employ the same methods that ceramic artists were experimenting with in my grandpa’s classes. What seems new about post-millennial pottery is its commitment to disharmony, and the aesthetic skills required of knowing how to botch, and when to stop.

The Exposed Materials show was reflective of a wider turn in visual culture away from the minimalism of millennial aesthetics, and towards a loud and maximalist aesthetic of bricolage. The most notable version of this is so-called ‘ugly fashion’, adopted by trendier millennials and zoomers, where outfits are curated from the tackiest op-shop finds and designer-wear of the 90’s and 2000’s: Crocs, Birkenstocks, belt chains, cargo shorts, flame patterns and raver-wear. Initially a reaction to the ‘don’t stand out’ mentality of normcore and paisley frailty of Pigeonholean indie, dressing fashionably-terrible was a way to flaunt your superior taste-in-bad-taste without being seen as shallow, elitist or consumerist. But as the aesthetic stopped being an op-shop affair and was adopted by high end fashion designers, a particular brand of ‘ugliness’ was prized, requiring high amounts of cultural and financial capital to participate.

For this reason, I feel like the term ‘ugly’ is misleading, and the bloated term post-millennial aesthetics feels appropriate[12]. This aesthetic goes beyond fashion and pottery into other visual forms: tattoos, jewellery, digital art and graphic design. Neon chains covered in goop and spikes can be found all over instagram and people’s bodies. The Gen Z revival of mid-2000s MySpace aesthetics dominates Tumblr, TikTok, and has given birth to the MySpace revival clone SpaceHey. While the excesses of post-millennial aesthetics are a refreshing change from their precursor’s blandness, and offer more potential for sincere artistic expression than the radical stupidity of Weed Craft; it still runs into the same problems as other cultural movements. As soon as it becomes familiar enough to label and emulate, it loses its radical cultural function.

Conclusion

If newness in art emerges from a repulsion with the surrounding culture, then there will never be an end to the progression of aesthetic movements. While there is no apparent ‘great modernist project’ and the only grand projects of contemporaneity are self, health and wealth… there is no end! No cliff for the lemmings, only brick walls. As Bill Callahan said ‘no matter how wrong you gone, you can always turn around’. As we saw through the recent pottery revival, techniques, mediums, and styles may come back full circle, but never the same way; each aesthetic trend a reflection of what the surrounding culture desires, and, more importantly, desires no longer.

My grandpa is in the ocean, riding a ghost yacht. The other week in his drawer I found a cartoon by a former student. In it a crowd of gawkers stand round a nude man on a stretcher. A nun carries in a bedpan reading ‘TEDEUM’. Unimpressed, my grandpa pats his smock, a speech bubble rising from his red bushy beard reading: ‘ceramically speaking sister, I think it may have been done before’. Don’t ask me what it means.

Footnotes:

1. See Arthur Danto’s essay ‘The End of Art’ (1984)

2. Lutyens, 2021

3. Yet like wonky pottery, the handcrafted earthcore pottery aesthetics of the late 60s were imitated by manufacturers such as Arabia Finland and reproduced on mass scale. Google the ruska series if you want a clear idea.

4. Other artforms that were less successful at surviving the 1970s Craft revival were macrame, crochet clothes, needlepoint by numbers and, I guess, pet rocks.

5. For more on millennial aesthetics, see Brad Tromel’s video essay Pastel Hell (2021)

6. Ngai, 2012

7. It’s neat that the word cute also follows the same etymological fluffening, shortened from the root word acute. Imagine that! The world’s sharpest angle made round.

8. Holm, 2022

9. Roper, 2021

10. Hohendahl, 2013

11. Beech, 2005

12. I will side with gen z by not calling it zoomer aesthetics

References:

Adorno, T. W. (1997). Aesthetic theory. Continuum.

Beech, D. (2005). The art of skill. Art Monthly, 290, 1-4.

Fischer, M. (2020). The tyranny of Terrazzo: Will the millenial aesthetic ever end? https://www.thecut.com/2020/03/will-the-millennial-aestheticever-end.html

Harris, D. (2000). Cute quaint, hungry, romantic: The aesthetics of consumerism. Basic Books.

Hohendahl, P. U. (2013). The fleeting promise of art: Adorno's aesthetic theory revisited. Cornell University Press.

Holm, N. (2022). No more jokes: Comic complexity, Adult Swim and a political aesthetic model of humour. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(2), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494221087296

Lutyens, D. (2021). Why the slow mindful craft of pottery is booming worldwide. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210428-why-theslow-mindful-craft-of-pottery-is-bo oming-worldwide

Ngai, S. (2012). Our aesthetic categories: Zany, cute, interesting. Harvard University Press.

Rivera, P. (2018). Normcore: Ugly is the New Normal. https://medium.com/@patriciariv/normcore-ugly-is-the-normal-6f76e7f15810

Roberts, J. (2010). Art after deskilling. Historical Materialism, 18, 77-96.

Roper, D. (2022). [@superchillandcool420]. (2020, February 5). Back in 2012 there was a lot of bullshit ceramics… [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/B8KkXrRFowM/ Roper, D. (2022). [@weedcraft2.0].

WEED-CRAFT2.0. https://www.instagram.com/weedcraft2.0/

Side Gallery. (2022). Exposed material. Side Gallery. https://side-gallery.com/exhibition/exposed-material-2022/#11

Troemel, B. (2021, September 13). Pastell hell: The definitive guide to millenial aesthetics [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qnX_S74jyq8

Vogue. (2017). Pottery is the new yoga! Here's to the mind-clearing benefits of clay. https://www.vogue.com/article/ceramics-pottery-therapeuticbenefits-Mindfulness-medita tion

Image credits: Images courtesy of the author, with artwork credits captioned.