It was three days out from Christmas. More importantly to me, it was two days out from the opening of Something for Everyone, a showing of the titular work by Olia Lialina at Bill’s PC. Bill’s PC launched in September of last year, exhibiting a work by the Tokyo-based artist COBRA (reviewed here by Francis Russell), followed by an appealing display of Nihaal Faizal’s (video art), an ever-expanding mega-playlist of unauthorised footage of video art.

Run by artist Matthew Brown, Bill’s PC bookended 2023 with net art pioneer Olia Lialina, a Western Australian first for the Russian-born artist. Since the mid-1990s, Lialina has been presenting experimental internet art, much of which is available at her online archive, art.teleportacia.org.

Art Teleportacia is a digital cacophony of Lialina’s interrelated and referential projects. Traversing her expansive oeuvre is an investigative endeavour, filled with seductively obscure interactive digital works and unusual narratives told through hypertext. Among the most influential of her works is My Boyfriend Came Back from the War (hereafter MBCBFTW).[1] Since the 1996 original, several versions of MBCBFTW have been created by Lialina and others, including an adaptation by JODI (web artist duo Dirk Paesmans and Joan Heemskerk) using a Wolfenstein mod.[2] In the mid-1990s, Lialina created an additional version which was sold to the German internet magazine Telepolis, making MBCBFTW the first web artwork ever sold.[3]

With my (perhaps rather ill-informed) mental image of Olia Lialina as “preeminent cyberpunk net art trailblazer”, I was surprised to see four customised advent calendars carefully mounted on the storeroom walls of Bill’s PC. Something for Everyone is one work—the four calendars—and a snapshot of a particular family tradition. Each November, Lialina’s husband, net artist and 8-bit musician Dragan Espenschied, searches the internet for a pleasing image for each family member, uploading them to a print-on-demand service. The customised advent calendars are then used by the couple and their two children during the festive season.

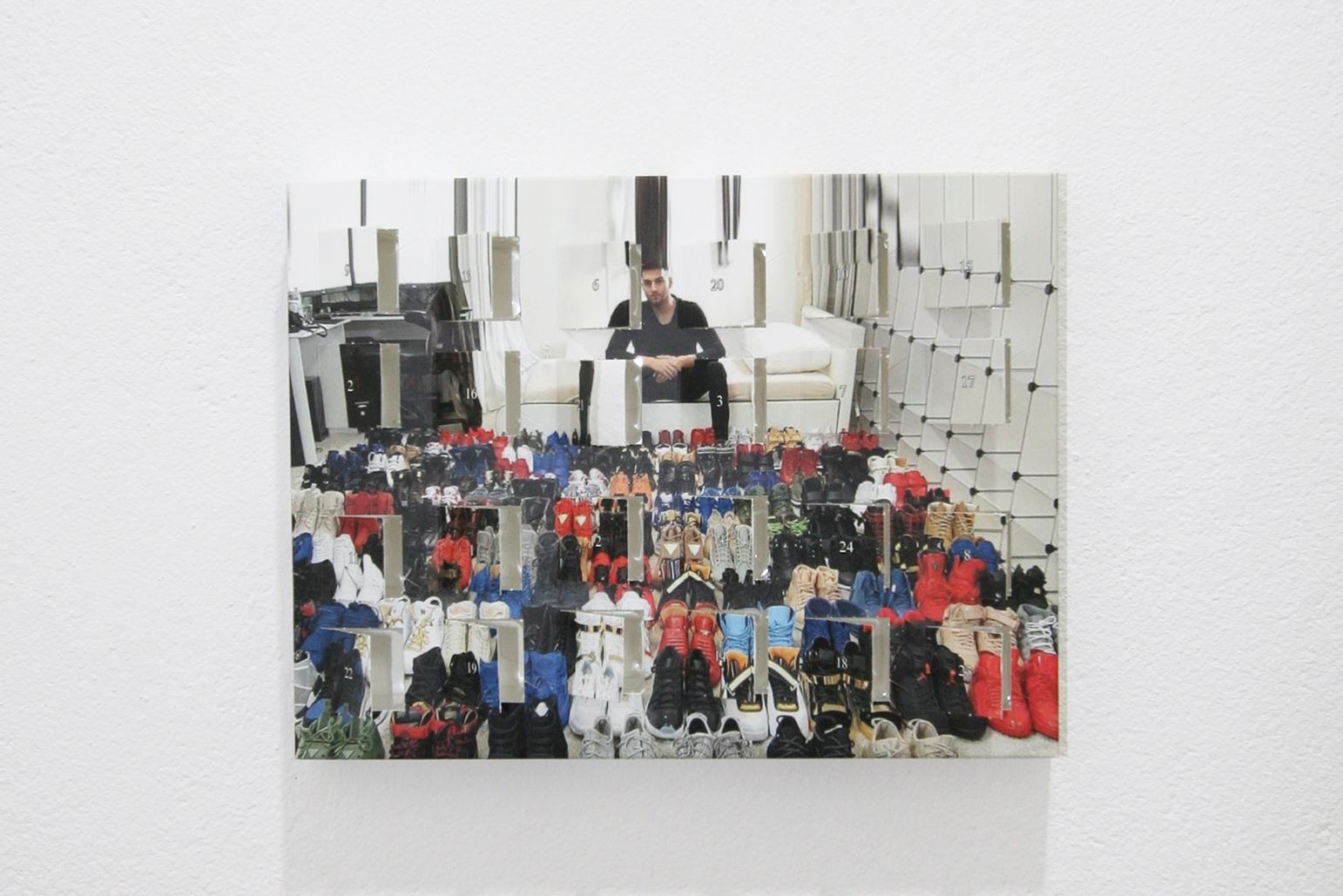

The four 2016 calendars became artworks the following year, displayed at Art Projects Ibiza in Asymmetrical Response. The exhibition was the first collaboration between Lialina and fellow media artist Cory Arcangel. Lialina’s four chocolate-stained readymade artworks sat in a row, enclosed in acryl-glass plinths. Personal kitsch-turned-cultural artefact, this capsule of a family’s cultural fascinations included images of: Vladimir Putin with his Karakachan dog Buffy gifted by the then Belgian prime minister Boyko Borisov; David Guetta in a scene from the music video for hit Dangerous, in which Guetta goes head-to-head against English actor James Purefoy on the Formula 1 track with the assistance of a bevy of sexy female mechanics ensuring the racecars are primed and ready; a famous scene from Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli classic, My Neighbor Totoro; and German YouTuber and self-proclaimed “King of Sneaker” ApoRed with over 130 pairs of sneakers.[4] They are curious images and intimate objects. At once sincere in familial intent, trashy and humorous, and, in the 2017 show, abstracted into archival artefact.

Six years later the works are mounted like small paintings on the walls of Bill’s PC. They are no longer artefacts best kept in art museum vitrines, but wall-mounted readymades; almost images as opposed to objects. This presentation (or perhaps modification) of the work had me judging them in what I imagine to be a very different light from their 2017 display. Inspecting the advent calendars, I spy the sticky remnants of 8-year-old chocolate and the increasingly fragile “hinges” of the calendar doors. Each semi-pixelated image is partially distorted by their layout. I cannot shake the urge to think through these objects as images—Guetta’s portrait appearing disfigured, his face peeled forward atop one of the doors. Familial (and perhaps banal) ritual and internet culture collide.

The variance between the 2017 and 2023 display of Something for Everyone speaks to the continued adaptation, modification, and reinvention that Lialina enthusiastically undertakes on her work—much like with My Boyfriend Came Back from the War nearly 30 years prior. It must be noted that the title of Lialina’s work is borrowed from a line in Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno’s The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. The essay puts forth that the consumable nature of popular culture lulls society into passivity. If Adorno could have seen Lialina’s advent calendars, I have no doubt he would have been left scratching his baldpate, troubled by whether the work transgresses or affirms his fears for what the future held for culture under capitalism. But it does transgress. Put simply, while the work utilises mass culture, it is also far too obtuse to be easily consumable. Or, to quote from The Culture Industry:

When I visited the exhibition, over a “cup of Joe”, Matthew Brown discussed the work, how the year had been, and what lay ahead. Brown’s outlook and vision for Bill’s PC yields an ambience in pitch-perfect harmony with that of Olia Lialina’s work—a seriousness about the work, an easiness toward experimentation, and a wittiness that is never conceited.

Perhaps all this is partially why Brown and Bill’s PC made it on to a list of “tastemakers” in the most recent edition of Art Collector. While it is excellent that the gallery and its manager have received such attention from a national publication like Art Collector, the noun bestowed seems at odds with the hyper-focused intention of the project: a tastemaker being “one who sets the standards of what is currently popular or fashionable”.[5] It appears to me that Brown has little interest in “tastemaking”. Rather, he is actively entrenched in a scene that has its own heroes, history, code of conduct, and methodologies; a scene that I believe is approaching definition, which it has so far evaded. An ism in the making? Certainly not. And any definition will likely be of little interest to its practitioners. Perhaps that is a part of the appealing gambit of these small exhibition spaces—galleries like Bill’s PC, Joshua Abelow’s Freddy, Josh Krum and Aden Miller’s Asbestos, David Attwood’s Disneyland Paris, or Bradford Kessler’s Kunsthalle Wichita to name but a few—, that they simultaneously operate within and outside of the dominant paradigms of contemporary art and its markets.

[1] A version of which is available at https://sites.rhizome.org/anthology/lialina.html

[2] Only scant information is available about this particular adaptation.

[3] https://www.josephinebosma.com/reviewing/44-olia-lialina-20-years-of-my-boyfriend-came-back-from-the-war?highlight=WyJsaWFsaW5hIl0=

[4] https://www.facebook.com/xApokalyptoRedx/photos/a.651319854879175/1247748781902943/?type=3

[5] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tastemaker

Photographs of Olia Lialina’s Something for Everyone at Bill’s PC, courtesy of Matthew Brown.

Run by artist Matthew Brown, Bill’s PC bookended 2023 with net art pioneer Olia Lialina, a Western Australian first for the Russian-born artist. Since the mid-1990s, Lialina has been presenting experimental internet art, much of which is available at her online archive, art.teleportacia.org.

Art Teleportacia is a digital cacophony of Lialina’s interrelated and referential projects. Traversing her expansive oeuvre is an investigative endeavour, filled with seductively obscure interactive digital works and unusual narratives told through hypertext. Among the most influential of her works is My Boyfriend Came Back from the War (hereafter MBCBFTW).[1] Since the 1996 original, several versions of MBCBFTW have been created by Lialina and others, including an adaptation by JODI (web artist duo Dirk Paesmans and Joan Heemskerk) using a Wolfenstein mod.[2] In the mid-1990s, Lialina created an additional version which was sold to the German internet magazine Telepolis, making MBCBFTW the first web artwork ever sold.[3]

With my (perhaps rather ill-informed) mental image of Olia Lialina as “preeminent cyberpunk net art trailblazer”, I was surprised to see four customised advent calendars carefully mounted on the storeroom walls of Bill’s PC. Something for Everyone is one work—the four calendars—and a snapshot of a particular family tradition. Each November, Lialina’s husband, net artist and 8-bit musician Dragan Espenschied, searches the internet for a pleasing image for each family member, uploading them to a print-on-demand service. The customised advent calendars are then used by the couple and their two children during the festive season.

The four 2016 calendars became artworks the following year, displayed at Art Projects Ibiza in Asymmetrical Response. The exhibition was the first collaboration between Lialina and fellow media artist Cory Arcangel. Lialina’s four chocolate-stained readymade artworks sat in a row, enclosed in acryl-glass plinths. Personal kitsch-turned-cultural artefact, this capsule of a family’s cultural fascinations included images of: Vladimir Putin with his Karakachan dog Buffy gifted by the then Belgian prime minister Boyko Borisov; David Guetta in a scene from the music video for hit Dangerous, in which Guetta goes head-to-head against English actor James Purefoy on the Formula 1 track with the assistance of a bevy of sexy female mechanics ensuring the racecars are primed and ready; a famous scene from Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli classic, My Neighbor Totoro; and German YouTuber and self-proclaimed “King of Sneaker” ApoRed with over 130 pairs of sneakers.[4] They are curious images and intimate objects. At once sincere in familial intent, trashy and humorous, and, in the 2017 show, abstracted into archival artefact.

Six years later the works are mounted like small paintings on the walls of Bill’s PC. They are no longer artefacts best kept in art museum vitrines, but wall-mounted readymades; almost images as opposed to objects. This presentation (or perhaps modification) of the work had me judging them in what I imagine to be a very different light from their 2017 display. Inspecting the advent calendars, I spy the sticky remnants of 8-year-old chocolate and the increasingly fragile “hinges” of the calendar doors. Each semi-pixelated image is partially distorted by their layout. I cannot shake the urge to think through these objects as images—Guetta’s portrait appearing disfigured, his face peeled forward atop one of the doors. Familial (and perhaps banal) ritual and internet culture collide.

The variance between the 2017 and 2023 display of Something for Everyone speaks to the continued adaptation, modification, and reinvention that Lialina enthusiastically undertakes on her work—much like with My Boyfriend Came Back from the War nearly 30 years prior. It must be noted that the title of Lialina’s work is borrowed from a line in Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno’s The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. The essay puts forth that the consumable nature of popular culture lulls society into passivity. If Adorno could have seen Lialina’s advent calendars, I have no doubt he would have been left scratching his baldpate, troubled by whether the work transgresses or affirms his fears for what the future held for culture under capitalism. But it does transgress. Put simply, while the work utilises mass culture, it is also far too obtuse to be easily consumable. Or, to quote from The Culture Industry:

Pure works of art, which negated the commodity character of society by simply following their own inherent laws, were at the same time always commodities. [...] The purposelessness of the great modern work of art is sustained by the anonymity of the market.

When I visited the exhibition, over a “cup of Joe”, Matthew Brown discussed the work, how the year had been, and what lay ahead. Brown’s outlook and vision for Bill’s PC yields an ambience in pitch-perfect harmony with that of Olia Lialina’s work—a seriousness about the work, an easiness toward experimentation, and a wittiness that is never conceited.

Perhaps all this is partially why Brown and Bill’s PC made it on to a list of “tastemakers” in the most recent edition of Art Collector. While it is excellent that the gallery and its manager have received such attention from a national publication like Art Collector, the noun bestowed seems at odds with the hyper-focused intention of the project: a tastemaker being “one who sets the standards of what is currently popular or fashionable”.[5] It appears to me that Brown has little interest in “tastemaking”. Rather, he is actively entrenched in a scene that has its own heroes, history, code of conduct, and methodologies; a scene that I believe is approaching definition, which it has so far evaded. An ism in the making? Certainly not. And any definition will likely be of little interest to its practitioners. Perhaps that is a part of the appealing gambit of these small exhibition spaces—galleries like Bill’s PC, Joshua Abelow’s Freddy, Josh Krum and Aden Miller’s Asbestos, David Attwood’s Disneyland Paris, or Bradford Kessler’s Kunsthalle Wichita to name but a few—, that they simultaneously operate within and outside of the dominant paradigms of contemporary art and its markets.

[1] A version of which is available at https://sites.rhizome.org/anthology/lialina.html

[2] Only scant information is available about this particular adaptation.

[3] https://www.josephinebosma.com/reviewing/44-olia-lialina-20-years-of-my-boyfriend-came-back-from-the-war?highlight=WyJsaWFsaW5hIl0=

[4] https://www.facebook.com/xApokalyptoRedx/photos/a.651319854879175/1247748781902943/?type=3

[5] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tastemaker

Photographs of Olia Lialina’s Something for Everyone at Bill’s PC, courtesy of Matthew Brown.