It was 40 degrees celsius at Boorloo, Perth station when boarding the train bound for Walyalup, Fremantle on Thursday, February 1st. Gazing out as we pulled into town, the mass of shipping containers, unwavering lifting cranes and a blinding white ensemble of new toyota hilux utes came together to form an image of neoliberalism’s organisation of dug up metals, minerals and fuels—a thematic primer that anticipated the exhibition at PS Arts Space.

Open cut, closed loop, curated by Chantelle Mitchell and Jaxon Waterhouse, brings together two video works: Regina de Miguel’s Nekya, A River Film (2023) and Georgia Nowak & Eugene Perepletchikov’s Aurum (2020) at PS Art Space in the port city of Walyalup. Docked from January 27 to February 11, the project surfaces in the mining empire of Western Australia, and explores how histories of extractivism can operate as a central node between disciplinary understandings. It is a nexus of connections between the logistics of late-capitalism; our archaic, insatiable desire to dig; the origins of subsurface resources; life under extreme circumstances on our planet; and the potentiality of existence on others—all of these strata are present in the show.

One might expect a fairly derivative message from a mining themed exhibition opening in the industrial embodiment of cargo-logistics—a waterside town located within the extraction-state of the country. However, the show’s intentions stem from a place of curiosity and ideation, rather than relying solely on conclusive histories of mine sites (of which there are plenty) to construct a purely documentary outcome. De Miguel and Nowak & Perepletchikovs’ videos synthesise an extractivist conspiracy; an exploratory overview of how cosmic forces and earthly materials are in cahoots. The show teeters around a question at the core Urbanomic Press’ Hydroplutonic Kernow (a 2020 publication that tracks a separate site-specific geophilosophy project in Cornwall, England); “Was it us harnessing the loop, or the loop harnessing us? Put differently, did we penetrate the earth—by burning fossilised sunlight—or did the earth coax us down into it?” [1] This meandering research makes a compelling case for collusion between the extraterrestrial origin of life and much sought after, contested mineral and ore deposits; the two working together, coaxing us into drilling downwards towards our own demise. As reflected in the first century AD by Pliny the Elder:

We see this archaic epigraph maintain its relevance in Open cut, closed loop’s investigations of the geotrauma-impact of our obsession with reopening wounds of the earth over and over to extract riches and knowledge of the universe. I couldn’t help but analyse the works’ creative methodology through the lens of what is termed speculative art practice—a label that runs rampant in contemporary art discourse. It has come to denote an aesthetic rendering of a set of (loose) philosophical postulates concerning our intermeshed world of material and social forces. It can be understood as a broad inquiry into how aesthetics, images, and creative forms of representation reflect the reality of our world, without being entirely constitutive of it. In other words, speculative aesthetics recognises that art always encodes and transmutates the reality at hand. From this understanding, it offers a framework for exploring potential connections between often sporadic objects, images and aesthetics that spur novel ontological hypotheses “[...] that both occults and doubles its epistemological conceits.” [3] The exhibition takes this very approach towards reprocessing extractivism’s pervasive past, reflecting on the geotrauma of the present and musing on its enduring legacy. It does so by drawing theoretical links between contested sites and histories of extraction, Greek mythology, archaeological research and geological deep time, all welded together via sci-fi tropes and structuralist film conventions. Ultimately, this amounts to an outcome that unravels several separate, yet connected fields of research in a way that expands our conception of mining beyond that of the resource industrial complex outward in all directions. This is achieved through drawing from hard-science, enduring histories and curious folklore to conjure up a refreshing epistemology of extraction. From the archaic pits of the Riotinto basin in Andalusia, Spain, to future extraction projects on Mars, Open cut, closed loop leaps back and forth before the dust momentarily settles in the sweltering summer heat of Australia’s mining capita. Squinting through these harsh conditions, one gets a hazy, yet expansive, view of geotrauma’s past, present and future.

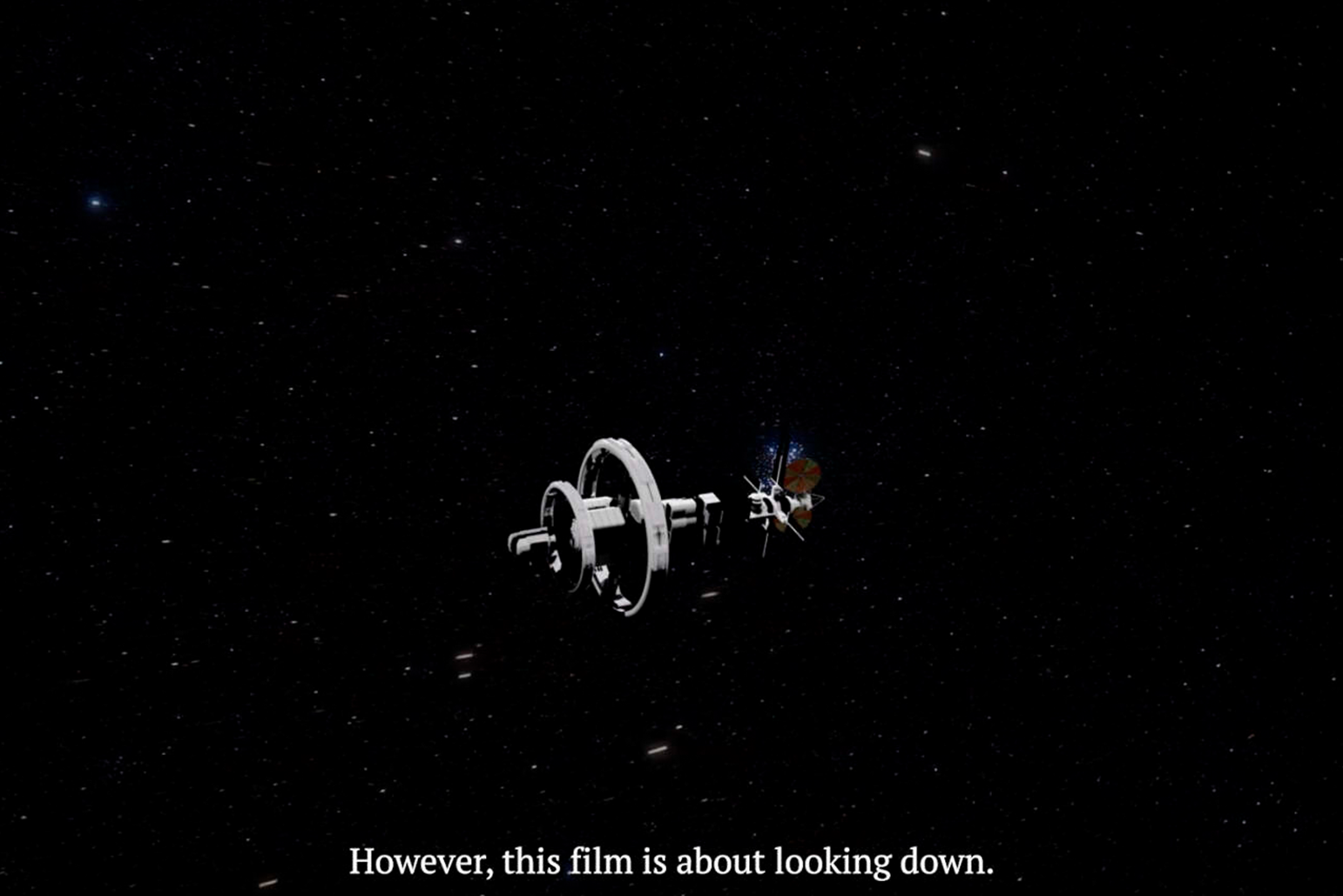

While the mind may “soar aloft” in the cavernous downstairs exhibition space of PSAS, de Miguel reminds us that, at its core, this exhibition “is about looking down.” [4] Her 74 minute speculative documentary-cross-sci-fi epic begins with a Kubrick-esque shot of a shuttle floating through the abyss of space. A narrator speaks in Spanish (with accompanying subtitles) deliberating on the theory that life on Earth was brought here with the first comets and meteorites. This notion suggests the pivotal role played by extremophiles, organisms that can endure extreme conditions, warrant a modern sort of “bio-prospecting” by astrobiologists with joint interests in underground life. As the film progresses, de Miguel winds the clocks back, to a montage of ancient scenes on a microscopic level that document the evolution of life and its shaping of our subsurface earthly world. We bear witness to menacing cave systems that carry water and minerals via slow, brooding animations, before landing on an image of stalactites and stalagmites. Illuminated by the water's reflection shimmering up at the cave ceiling, these upwards and downwards mounds of mineral deposits angle themselves at each other, nodding to the fact that the little critters found in such deep and extreme environments below may have origins that lie above in the stars.

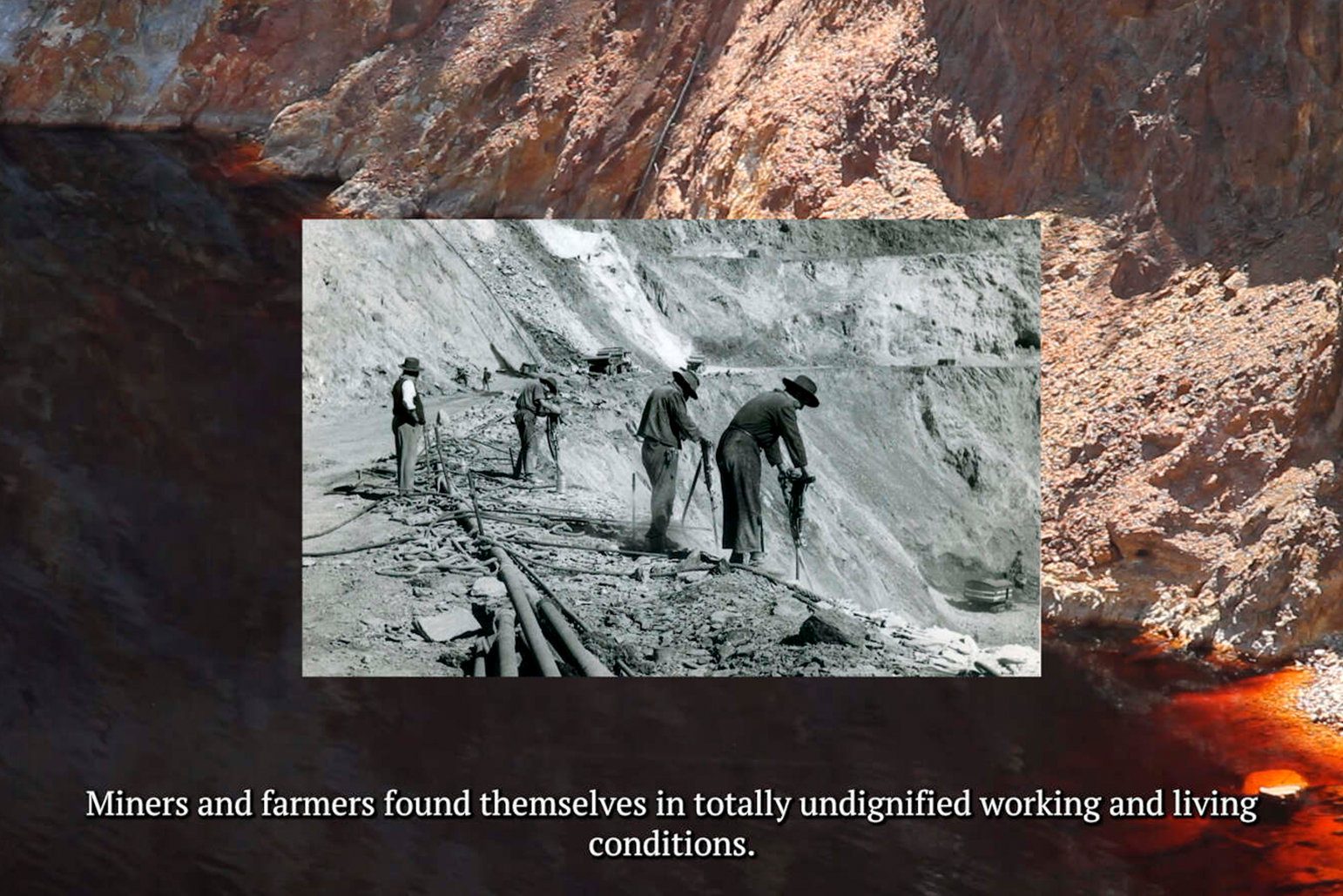

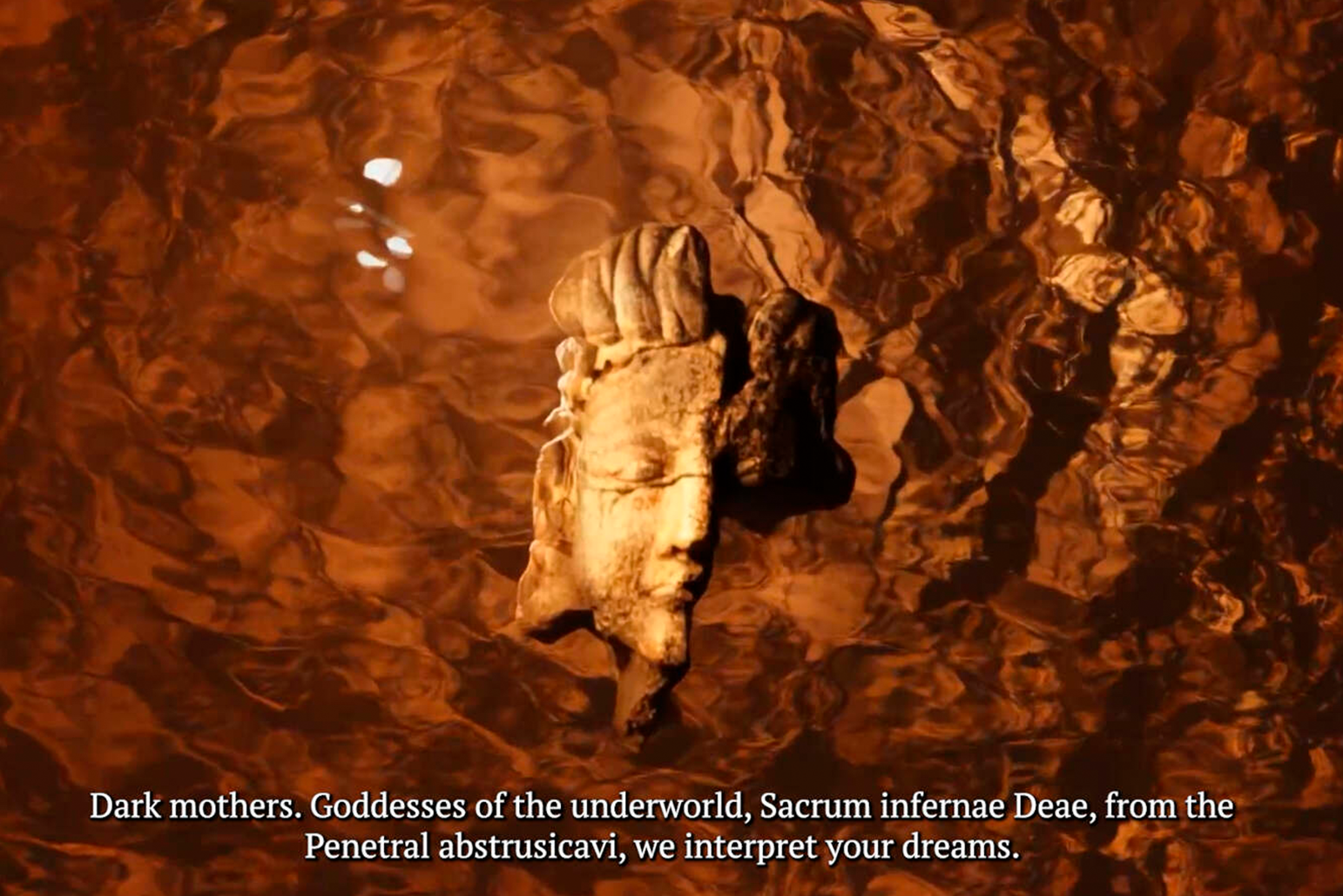

During this poetic acknowledgement between matter coming down and complex structures moving up, a narrative of life forged in the hellish extremes of the subsurface is conveyed. Enter Goddesses of the underworld: “Astart, Ishtar, Hecate, Medea, Persphone, Proserpina, Gaia, Medusa”, the narrator rattles off through “a fiery monody from the underground.” [5] Hecate (a chthonic Goddess of necromancy and liminal spaces between worlds) plays an important role here in transporting us to the Riotinto basin; the site-specific locus central to de Miguel’s narrative, and from where the mining company takes its name. The largest hectacomb (a bloody offering of more than a hundred animals sacrificed to Hecate) in the West is found here. “These rites were linked to the cycles of death and life, but also to the seasons and harvests.” [6] The territory is widely regarded as one of the most important mining districts of antiquity, with evidence of mining projects dating back to 3000 BC. [7] Taking up the middle chunk of this expansive odyssey, the narrator unravels the tumultuous facts of late 19th and early 20th century mining practices of the region. An 1888 massacre that saw anti-smoke league agriculturists and Andalusian miners protest for safer work conditions showcases our class societies’ ancient extractivist compulsion at a horrific modern boiling point. Here, the narrator transitions from geological deep time and Greek mythology to interviews with archaeologists, astrobiologists, and a descendant of one of the eighteen murdered miners who had marched to Riotinto town hall, fired upon by the Spanish civil guard. This era of the basin mining operation saw pollution caused by mineral extraction; the enslavement of the local population; and the collusion of a corrupt government with the British Rio Tinto mining company. Beyond a compelling historical case study of extraction, de Miguel’s fusing of eerie sci-fi animations, Greek odysseys of underworld goddesses, archival imagery, and engagement with contemporary researchers makes this film a dense, ambitious and compelling effort.

Similarly, Aurum is an essay film that teases out the boundaries between history and mythology. As the Spanish artist’s film came to a close, I repositioned myself, switching from one half-tonne limestone-rock-turned-seat to another, and settled into the considerably shorter second half of the exhibition. At 21 minutes, Aurum is less of a slow burn than the Nekya film, asserting an accelerated atmosphere which matches its foreboding narration. We see the narrative convention switch from site-specificity to material-specificity, as Nowak & Perepletchikov’s video opts for a single resource case study, expanding our focus out from the Riotinto basin to investigate gold at a global level. As a material that has shaped civilizations and is a token of wealth and prestige, gold is approached by the duo as a resource with worth that lies mostly in its exchange value. Nowak and Perepletchikov use their film to frame gold as perhaps the most clear expression of commodity fetishism; even in its most unprocessed forms, our cultural systems place a metaphysical and theological worth behind it. [8] The film’s narrator repeats on several occasions, “the value of gold lies in our belief in the value of gold.” [9] A captivating protagonist to this story, gold makes an apt central figure for an extractivism case study as it physically resists decay and endures all sorts of extreme conditions with pride and power. The film begins with describing the collision of two neutron stars that shoot debris containing massive quantities of platinum, silver and gold. Like de Miguel’s work, this premise is succeeded by a litany of fables from bygone ages: Ra, the sun God of ancient Egypt (the creator of all Egyptian Gods); Inti, the Sun God of the Incas (who sheds gold tears onto the earth); and Caesar (the first Roman to have an effigy on a gold coin during his lifetime) to name a few. From here, a desaturated montage of aerial extraction site footage, minting operations, and coin stamping follows. This gritty documentation of gold’s industrialised extraction and laborious manipulation is intertwined with spectral imagery of its plating on computer motherboard circuitry and spacecraft insulation—uses owing to the material’s conductive properties and refusal to corrode. Overviewing more than 7000 years of gold mining, Aurum presents an essay reminding us that whilst bodies break down and people turn to dust, wealth builds up and gold endures.

The circular nature of extractivism whereby industrialists, labourers and Gods continually return to the deep earth is mimicked by the screening cycles, with Nekya’s loop beginning as Aurum’s ends. Over the course of 90-odd minutes, Nekya and Aurum work concurrently, constructing a montage of sparse archival footage, ghostly animations and suspenseful drone shots as a pertinent reminder of the image-politics that art produces, as well as their contingent nature. Open cut, closed loop basks in art’s mediating capacity, a testament to the fact that “to take the image seriously is to understand how images exact force,” as artist and writer Amanda Beech frames it. [10] The show appears to consciously pursue the political ramifications and speculative potentials for imagining seemingly distant connections between scattered materials, histories and lore. Research-based artists of the science/technology/art matrix have a tendency to underscore themselves with ‘scientific’ methodologies in order to do away art’s mediation of reality, as if this would be getting to the “real truth” of the thing at hand. Instead, de Miguel, Nowak and Perepletchikov bolster speculative aesthetics via interdisciplinary research in a way that effectively dives head first into the idea of the art image-as-mediator. This decision’s value lies in the notion that art produces images that are derived from reality, but these images are not wholly constitutive of it. As Beech asserts, “undoing the image to undo power.” [11] In other words, un-doing art in an attempt to undo its mediation of reality to reach a certain truth is a futile effort. Perhaps it's even fair to say that for all the dense extraction histories entangled with mythologies, theories, astrobiological origins, and speculations on future mining on a cosmic scale, Open cut, closed loop brings a critical attitude towards the apparent objectivity of “hard” scientific research.

The show is a stark reminder of the fact that even methodically researched, historically attentive creative projects cannot escape art's inevitable proclivity to encode. The assemblage of these interdisciplinary works under one exhibition frames this conundrum as a glass-half-full scenario: it poses that there is a great deal of merit in applying lofty speculative aesthetics as a form of creative research, as it unearths new epistemologies of extraction. Of course, this celebration of speculative art’s exciting generative capacities manifests through a grim tale of a theoretical “millenary chain” of extracted resources and human labour. [12] The exhibition espouses a speculative methodology that ought to be adopted by audiences and artists alike — an approach to storytelling that can be applied on the sending and receiving ends of art discourse. It’s ambitious, but not overly so; a long and tumultuous ride that, if stuck with, marks an impressive feat of being dense yet exploratory; demanding yet engaging.

Open cut, closed loop runs from 27 January - 11 February 2024 at PS Art Space.

Footnotes:

1. Robin Mackay ed., Hydroplutonic Kernow (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020), 12.

2. Max Wade, “Stoic Pantheism and Environmental Ethics in Pliny the Elder” in Luca Valera eds., Pantheism and Ecology: Cosmological, Theoretical and Philosophical Perspectives (Cham: Springer, 2023), 20, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40040-7_2.

3. Robin Mackay, Luke Pendrell and James Trafford eds., Speculative Aesthetics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014), 4.

4. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023), HD video and 3D animation.

5. Ibid.

6. Regina de Miguel, “Nekya, A River Film,” Regina de Miguel, 2023, https://www.reginademiguel.net/NEKYA-A-RIVER-FILM.

7. R. Davis Jr., A. Welty, J. Borrego, et al., “Rio Tinto estuary (Spain): 5000 years of pollution,” Environmental Geology 39 no. 10 (2000), 1107–1116, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002549900096.

8. Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Penguin, 1867; repr., 1990), 163.

9. Georgia Nowak, “Aurum,” Georgia Nowak, 2020, https://georgianowak.com/Aurum.

10. Mackay et al., Speculative Aesthetics, 17.

11. Ibid, 6.

12. de Miguel, “Nekya, A River Film.”

Image Credits:

1. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023, HD video and 3D animation, 1 hr 13 min, film still).

2. Georgia Nowak and Eugene Perepletchikov, Aurum (2020, 4K video, 21 min, 7 sec, film still).

3. Samuel Beilby, Open cut, closed loop exhibition documentation image.

4. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023, HD video and 3D animation, 1 hr 13 min, film still).

5. Georgia Nowak and Eugene Perepletchikov, Aurum (2020, 4K video, 21 min, 7 sec, film still).

6. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023, HD video and 3D animation, 1 hr 13 min, film still).

Open cut, closed loop, curated by Chantelle Mitchell and Jaxon Waterhouse, brings together two video works: Regina de Miguel’s Nekya, A River Film (2023) and Georgia Nowak & Eugene Perepletchikov’s Aurum (2020) at PS Art Space in the port city of Walyalup. Docked from January 27 to February 11, the project surfaces in the mining empire of Western Australia, and explores how histories of extractivism can operate as a central node between disciplinary understandings. It is a nexus of connections between the logistics of late-capitalism; our archaic, insatiable desire to dig; the origins of subsurface resources; life under extreme circumstances on our planet; and the potentiality of existence on others—all of these strata are present in the show.

One might expect a fairly derivative message from a mining themed exhibition opening in the industrial embodiment of cargo-logistics—a waterside town located within the extraction-state of the country. However, the show’s intentions stem from a place of curiosity and ideation, rather than relying solely on conclusive histories of mine sites (of which there are plenty) to construct a purely documentary outcome. De Miguel and Nowak & Perepletchikovs’ videos synthesise an extractivist conspiracy; an exploratory overview of how cosmic forces and earthly materials are in cahoots. The show teeters around a question at the core Urbanomic Press’ Hydroplutonic Kernow (a 2020 publication that tracks a separate site-specific geophilosophy project in Cornwall, England); “Was it us harnessing the loop, or the loop harnessing us? Put differently, did we penetrate the earth—by burning fossilised sunlight—or did the earth coax us down into it?” [1] This meandering research makes a compelling case for collusion between the extraterrestrial origin of life and much sought after, contested mineral and ore deposits; the two working together, coaxing us into drilling downwards towards our own demise. As reflected in the first century AD by Pliny the Elder:

The things that she has concealed and hidden underground [...] are the things that destroy us and drive us to the depths below; so that suddenly the mind soars aloft into the void and ponders what finally will be the end of draining her dry in all the ages, what will be the point to which avarice will penetrate. [2]

We see this archaic epigraph maintain its relevance in Open cut, closed loop’s investigations of the geotrauma-impact of our obsession with reopening wounds of the earth over and over to extract riches and knowledge of the universe. I couldn’t help but analyse the works’ creative methodology through the lens of what is termed speculative art practice—a label that runs rampant in contemporary art discourse. It has come to denote an aesthetic rendering of a set of (loose) philosophical postulates concerning our intermeshed world of material and social forces. It can be understood as a broad inquiry into how aesthetics, images, and creative forms of representation reflect the reality of our world, without being entirely constitutive of it. In other words, speculative aesthetics recognises that art always encodes and transmutates the reality at hand. From this understanding, it offers a framework for exploring potential connections between often sporadic objects, images and aesthetics that spur novel ontological hypotheses “[...] that both occults and doubles its epistemological conceits.” [3] The exhibition takes this very approach towards reprocessing extractivism’s pervasive past, reflecting on the geotrauma of the present and musing on its enduring legacy. It does so by drawing theoretical links between contested sites and histories of extraction, Greek mythology, archaeological research and geological deep time, all welded together via sci-fi tropes and structuralist film conventions. Ultimately, this amounts to an outcome that unravels several separate, yet connected fields of research in a way that expands our conception of mining beyond that of the resource industrial complex outward in all directions. This is achieved through drawing from hard-science, enduring histories and curious folklore to conjure up a refreshing epistemology of extraction. From the archaic pits of the Riotinto basin in Andalusia, Spain, to future extraction projects on Mars, Open cut, closed loop leaps back and forth before the dust momentarily settles in the sweltering summer heat of Australia’s mining capita. Squinting through these harsh conditions, one gets a hazy, yet expansive, view of geotrauma’s past, present and future.

While the mind may “soar aloft” in the cavernous downstairs exhibition space of PSAS, de Miguel reminds us that, at its core, this exhibition “is about looking down.” [4] Her 74 minute speculative documentary-cross-sci-fi epic begins with a Kubrick-esque shot of a shuttle floating through the abyss of space. A narrator speaks in Spanish (with accompanying subtitles) deliberating on the theory that life on Earth was brought here with the first comets and meteorites. This notion suggests the pivotal role played by extremophiles, organisms that can endure extreme conditions, warrant a modern sort of “bio-prospecting” by astrobiologists with joint interests in underground life. As the film progresses, de Miguel winds the clocks back, to a montage of ancient scenes on a microscopic level that document the evolution of life and its shaping of our subsurface earthly world. We bear witness to menacing cave systems that carry water and minerals via slow, brooding animations, before landing on an image of stalactites and stalagmites. Illuminated by the water's reflection shimmering up at the cave ceiling, these upwards and downwards mounds of mineral deposits angle themselves at each other, nodding to the fact that the little critters found in such deep and extreme environments below may have origins that lie above in the stars.

During this poetic acknowledgement between matter coming down and complex structures moving up, a narrative of life forged in the hellish extremes of the subsurface is conveyed. Enter Goddesses of the underworld: “Astart, Ishtar, Hecate, Medea, Persphone, Proserpina, Gaia, Medusa”, the narrator rattles off through “a fiery monody from the underground.” [5] Hecate (a chthonic Goddess of necromancy and liminal spaces between worlds) plays an important role here in transporting us to the Riotinto basin; the site-specific locus central to de Miguel’s narrative, and from where the mining company takes its name. The largest hectacomb (a bloody offering of more than a hundred animals sacrificed to Hecate) in the West is found here. “These rites were linked to the cycles of death and life, but also to the seasons and harvests.” [6] The territory is widely regarded as one of the most important mining districts of antiquity, with evidence of mining projects dating back to 3000 BC. [7] Taking up the middle chunk of this expansive odyssey, the narrator unravels the tumultuous facts of late 19th and early 20th century mining practices of the region. An 1888 massacre that saw anti-smoke league agriculturists and Andalusian miners protest for safer work conditions showcases our class societies’ ancient extractivist compulsion at a horrific modern boiling point. Here, the narrator transitions from geological deep time and Greek mythology to interviews with archaeologists, astrobiologists, and a descendant of one of the eighteen murdered miners who had marched to Riotinto town hall, fired upon by the Spanish civil guard. This era of the basin mining operation saw pollution caused by mineral extraction; the enslavement of the local population; and the collusion of a corrupt government with the British Rio Tinto mining company. Beyond a compelling historical case study of extraction, de Miguel’s fusing of eerie sci-fi animations, Greek odysseys of underworld goddesses, archival imagery, and engagement with contemporary researchers makes this film a dense, ambitious and compelling effort.

Similarly, Aurum is an essay film that teases out the boundaries between history and mythology. As the Spanish artist’s film came to a close, I repositioned myself, switching from one half-tonne limestone-rock-turned-seat to another, and settled into the considerably shorter second half of the exhibition. At 21 minutes, Aurum is less of a slow burn than the Nekya film, asserting an accelerated atmosphere which matches its foreboding narration. We see the narrative convention switch from site-specificity to material-specificity, as Nowak & Perepletchikov’s video opts for a single resource case study, expanding our focus out from the Riotinto basin to investigate gold at a global level. As a material that has shaped civilizations and is a token of wealth and prestige, gold is approached by the duo as a resource with worth that lies mostly in its exchange value. Nowak and Perepletchikov use their film to frame gold as perhaps the most clear expression of commodity fetishism; even in its most unprocessed forms, our cultural systems place a metaphysical and theological worth behind it. [8] The film’s narrator repeats on several occasions, “the value of gold lies in our belief in the value of gold.” [9] A captivating protagonist to this story, gold makes an apt central figure for an extractivism case study as it physically resists decay and endures all sorts of extreme conditions with pride and power. The film begins with describing the collision of two neutron stars that shoot debris containing massive quantities of platinum, silver and gold. Like de Miguel’s work, this premise is succeeded by a litany of fables from bygone ages: Ra, the sun God of ancient Egypt (the creator of all Egyptian Gods); Inti, the Sun God of the Incas (who sheds gold tears onto the earth); and Caesar (the first Roman to have an effigy on a gold coin during his lifetime) to name a few. From here, a desaturated montage of aerial extraction site footage, minting operations, and coin stamping follows. This gritty documentation of gold’s industrialised extraction and laborious manipulation is intertwined with spectral imagery of its plating on computer motherboard circuitry and spacecraft insulation—uses owing to the material’s conductive properties and refusal to corrode. Overviewing more than 7000 years of gold mining, Aurum presents an essay reminding us that whilst bodies break down and people turn to dust, wealth builds up and gold endures.

The circular nature of extractivism whereby industrialists, labourers and Gods continually return to the deep earth is mimicked by the screening cycles, with Nekya’s loop beginning as Aurum’s ends. Over the course of 90-odd minutes, Nekya and Aurum work concurrently, constructing a montage of sparse archival footage, ghostly animations and suspenseful drone shots as a pertinent reminder of the image-politics that art produces, as well as their contingent nature. Open cut, closed loop basks in art’s mediating capacity, a testament to the fact that “to take the image seriously is to understand how images exact force,” as artist and writer Amanda Beech frames it. [10] The show appears to consciously pursue the political ramifications and speculative potentials for imagining seemingly distant connections between scattered materials, histories and lore. Research-based artists of the science/technology/art matrix have a tendency to underscore themselves with ‘scientific’ methodologies in order to do away art’s mediation of reality, as if this would be getting to the “real truth” of the thing at hand. Instead, de Miguel, Nowak and Perepletchikov bolster speculative aesthetics via interdisciplinary research in a way that effectively dives head first into the idea of the art image-as-mediator. This decision’s value lies in the notion that art produces images that are derived from reality, but these images are not wholly constitutive of it. As Beech asserts, “undoing the image to undo power.” [11] In other words, un-doing art in an attempt to undo its mediation of reality to reach a certain truth is a futile effort. Perhaps it's even fair to say that for all the dense extraction histories entangled with mythologies, theories, astrobiological origins, and speculations on future mining on a cosmic scale, Open cut, closed loop brings a critical attitude towards the apparent objectivity of “hard” scientific research.

The show is a stark reminder of the fact that even methodically researched, historically attentive creative projects cannot escape art's inevitable proclivity to encode. The assemblage of these interdisciplinary works under one exhibition frames this conundrum as a glass-half-full scenario: it poses that there is a great deal of merit in applying lofty speculative aesthetics as a form of creative research, as it unearths new epistemologies of extraction. Of course, this celebration of speculative art’s exciting generative capacities manifests through a grim tale of a theoretical “millenary chain” of extracted resources and human labour. [12] The exhibition espouses a speculative methodology that ought to be adopted by audiences and artists alike — an approach to storytelling that can be applied on the sending and receiving ends of art discourse. It’s ambitious, but not overly so; a long and tumultuous ride that, if stuck with, marks an impressive feat of being dense yet exploratory; demanding yet engaging.

Open cut, closed loop runs from 27 January - 11 February 2024 at PS Art Space.

Footnotes:

1. Robin Mackay ed., Hydroplutonic Kernow (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020), 12.

2. Max Wade, “Stoic Pantheism and Environmental Ethics in Pliny the Elder” in Luca Valera eds., Pantheism and Ecology: Cosmological, Theoretical and Philosophical Perspectives (Cham: Springer, 2023), 20, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40040-7_2.

3. Robin Mackay, Luke Pendrell and James Trafford eds., Speculative Aesthetics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014), 4.

4. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023), HD video and 3D animation.

5. Ibid.

6. Regina de Miguel, “Nekya, A River Film,” Regina de Miguel, 2023, https://www.reginademiguel.net/NEKYA-A-RIVER-FILM.

7. R. Davis Jr., A. Welty, J. Borrego, et al., “Rio Tinto estuary (Spain): 5000 years of pollution,” Environmental Geology 39 no. 10 (2000), 1107–1116, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002549900096.

8. Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Penguin, 1867; repr., 1990), 163.

9. Georgia Nowak, “Aurum,” Georgia Nowak, 2020, https://georgianowak.com/Aurum.

10. Mackay et al., Speculative Aesthetics, 17.

11. Ibid, 6.

12. de Miguel, “Nekya, A River Film.”

Image Credits:

1. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023, HD video and 3D animation, 1 hr 13 min, film still).

2. Georgia Nowak and Eugene Perepletchikov, Aurum (2020, 4K video, 21 min, 7 sec, film still).

3. Samuel Beilby, Open cut, closed loop exhibition documentation image.

4. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023, HD video and 3D animation, 1 hr 13 min, film still).

5. Georgia Nowak and Eugene Perepletchikov, Aurum (2020, 4K video, 21 min, 7 sec, film still).

6. Regina de Miguel, Nekya, A River Film (2023, HD video and 3D animation, 1 hr 13 min, film still).