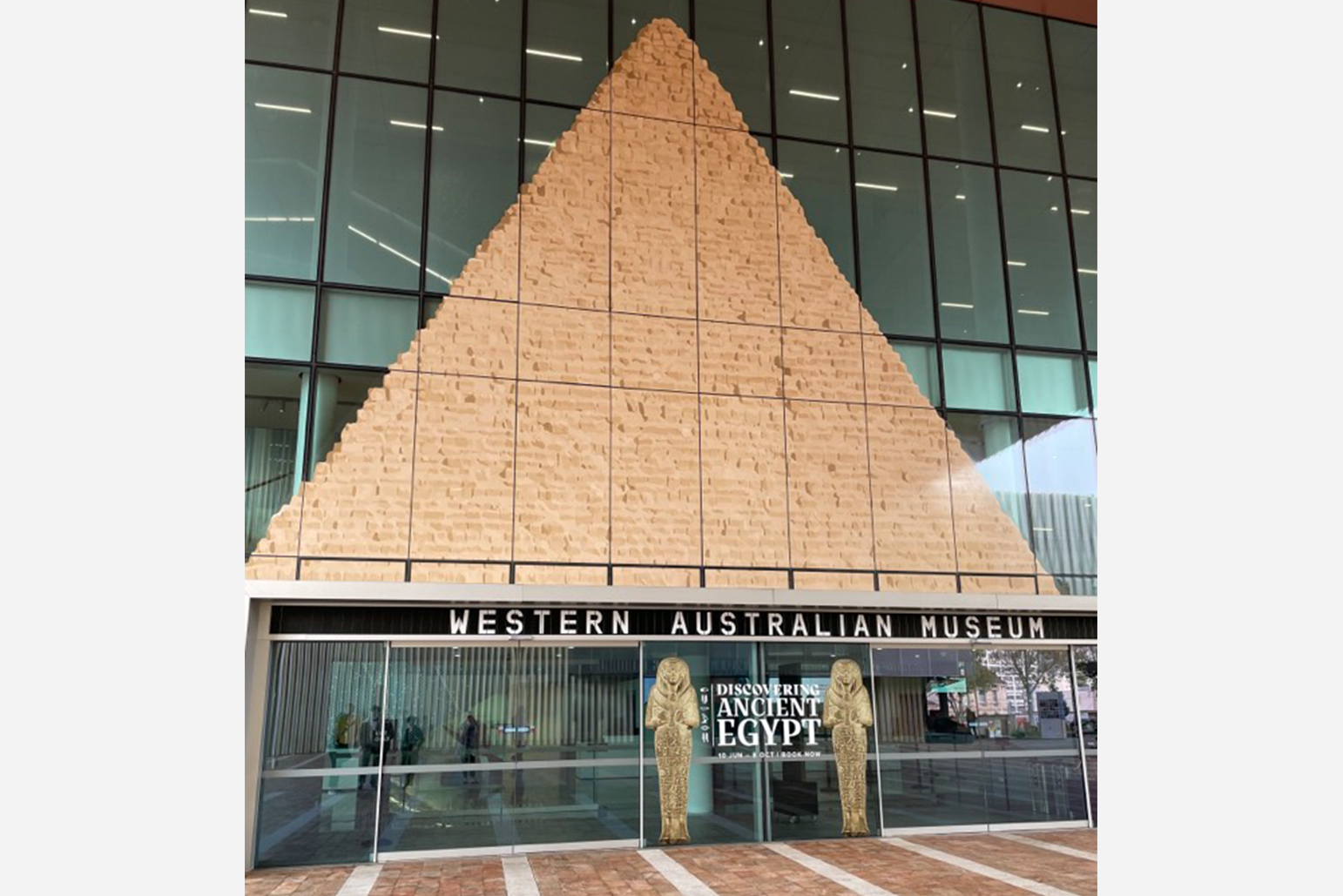

Discovering Ancient Egypt is the WA Museum Boola Bardip’s international blockbuster exhibition for the year, travelling all the way from the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (RMO). As I watch the introductory film—an animation cast over a replica of the Temple of Taffeh—I can’t help but think the timing of the exhibition is awkward. The key themes of Discovering Ancient Egypt orbit around the harmonious relations between Dutch and Egyptian research teams. Anyone keeping up with the latest politics in international museum discourse knows that the RMO had its Saqqara excavation permits revoked on June 6 of this year due to curatorial disagreements. Attending the exhibition opening four days later, the panels espousing the “unique partnership” shared between the RMO and Egyptian authorities leaves a stale taste in one’s mouth. This timing cannot be helped—the didactics were presumably planned and printed months before this controversy occurred. However, a feeling of silence lies heavy on the didactical interpretation of many objects throughout the exhibition.

I spent several hours in the exhibition and I am still uncertain as to the actual intent (beyond the customary ambitions for a blockbuster show). The title, Discovering Ancient Egypt, is an interesting choice. Is it the audience who are “discovering”? The Dutch? The exhibition is broadly split into three categories. The first is the strongest, where it breaks down the umbrella term of “Ancient Egypt” into distinct periods. The middle section revolves around the West’s “new perspectives” on Ancient Egypt and “obsession” with Egyptology towards the later part of the twentieth century. Heavily sanitised, it reads like a PR exercise for the RMO. I do not expect the interpretation to give a dissertation-long history of issues arising from the West’s exoticisation and exploitation of Egypt, but it reads like revisionism to not even mention such facts, and instead present them as harmless fascinations. Wall space that could have explored this context is instead occupied by panels explaining how the Egyptian government gifted a statue to the Dutch royal family, or how 17th century Dutch explorers apolitically “collected” mummies to cart home to Leiden.

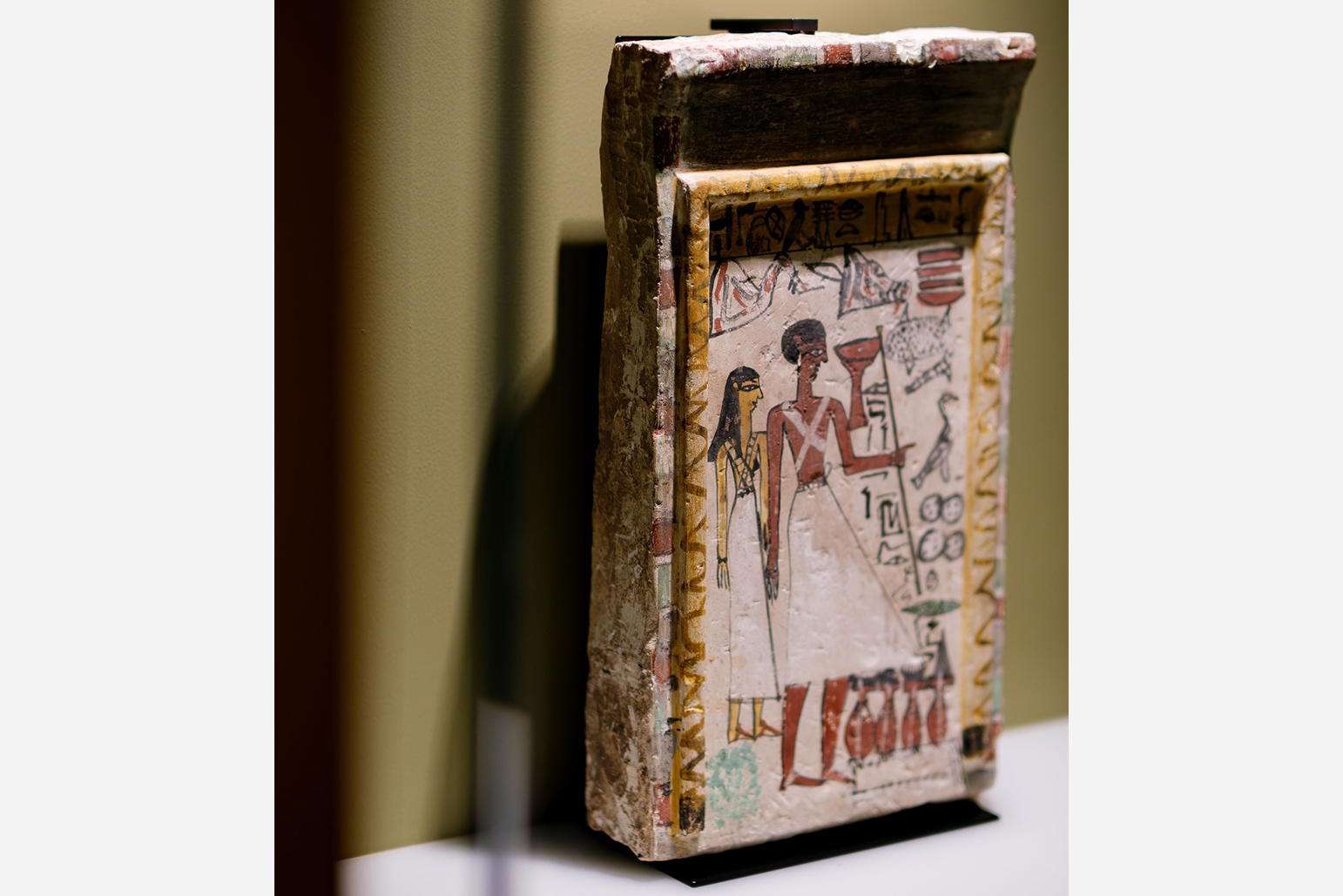

The final section of the exhibition relates to the Egyptian afterlife. This includes grave goods, funerary rituals, and of course, coffins and mummified human remains. As a touring exhibition, I doubt that Boola Bardip had any input into the didactic panels. What they do control is the advertising; the website features a two-sentence warning regarding the display of human remains. In contrast, the website for the National Museum of Australia (NMA)—the next institution to host the exhibition—handles the inclusion of remains not with a trigger warning, but as an opportunity for thought. “The existence of these remains prompts us all to think about profound questions relating to life and death,” the NMA’s site tells us. I wish WAM trusted their public enough to have hinted at such questions. Unfortunately, their marketing seems more invested in encouraging WA residents to “walk like an Egyptian” instead of encouraging any shred of critical thought.

I am undecided as to how I feel about human remains being displayed. It is not that I vehemently object to such displays, but I do think it is an interesting and necessary conversation to have concerning museums and their collections. This is an opportunity for the WA Museum to stimulate such dialogues. The biggest didactic in the “mummy annexe” is a panel on the x-ray process for investigating what lies beneath a mummified person’s linen bandages. The statement reassures the viewer that though “early scholars” unwrapped mummies to “study” them, now “non-invasive” scanning procedures are used. It rings like a platitude. Is keeping these bodies in their wrappings while shipping them around the world for the paying public somehow less invasive? They have already been taken from their eternal resting places, their possessions disseminated between countries, and stuck behind glass for kids to press their faces up against. The suggestion that those participating in past unwrappings were “scholars” seems misleading. The historic display of human remains is fraught with issues around respect and exploitation of the dead. Such an interpretation suggests to the public that those cutting up “mummies” were researchers doing so because the x-ray hadn’t been invented, when in fact, for many years, an industry of performative “mummy unwrappings” had been booming. Giovanni d’Athanasi, the dealer who sold the RMO their Book of the Dead of Qenna in 1835, hosted “mummy unravellings” in central London. Hundreds of punters would pack into an auditorium for hours to watch these bodies stripped, bandage by bandage. This procedure was not for research, but for public spectacle: to make money. This history was far more complex than the RMO’s exhibition would have us believe. This simplistic misrepresentation is a discursive block to understanding these historical nuances.

The decision to curate a historical exhibition so abstracted from the history it references is fascinating. To spend an hour reading about all the ways in which Ancient Egyptians would safeguard their burials—false doors, winding tombs, cartonnage coffins to prevent reuse—and then end with the display of bodies which, despite their best efforts, were turfed from their tombs, feels tone deaf, like an underhanded show of superiority. But what stays with me long after I left the exhibition is a didactic relating to the body of a mummified woman whose name is either Ta(net)kharu or Tadis. Her name was written on her coffin, but the panel informs us that “she was taken out of her coffin in the 19th century and confused with a similar looking mummy from another coffin”. This fact is presented uncritically, as if it was a common mix-up orchestrated by nobody in particular. Something that just happened. Whoops! Looking at Ta(net)kharu or Tadis I think about everything I have just learned in this very exhibition: the tiny shabtis designed to assist the dead in their afterlife, the linen amulets bearing spells to wrap around one’s body to protect those who had died, the intricate stories decorating coffins specific to that person’s life and favoured gods. Immediately prior to this room, the exhibition outlines many indicators of highly personalised funerary rituals pertaining to Ancient Egyptians. Presumably Ta(net)kharu or Tadis would have engaged in these same rituals, long before somebody came and nabbed her from her tomb and couldn’t be fucked recording her name properly. I guess they were just booting too many dead people out of their graves that day and it all got a little confusing—it happens!

Our histories are not clean. Sensibilities change. I am not expecting twenty-first century ideological purity from every archeologist or curator who came before; that line of thought is tedious and reductive. What I do want from my museum visits is to understand historical context, to be trusted with the full picture, to be encouraged to think about our past and present. The RMO, and by extension WAM, should trust their public to reflect critically on the artefacts in this exhibition. It will be interesting to see how the NMA handles these challenges. The 240 objects on display have a past, and surely to view them is more interesting when that past is contextualised? Why come to see objects in their physical form if the intent is to just snap a photo and move on, no questions asked? I was driven out of my mind while looking at the display about the Book of the Dead of Qenna, the longest written papyrus text in the RMO collection. The label states, in vague terms, that this object was chopped up into 38 pieces after being accessioned into the collection. Why was this action taken? Was this standard practice? Is chopping up manuscripts still done today, or is it frowned upon? Who knows! These vague, decontextualised statements fill the didactics throughout, and they provoke far more questions than they provide answers. We are told explicitly when the RMO has done things “correctly”, but the rest is silence.

Do these critiques matter? The exhibition is clearly a sell-out. Down at the front desk, I overhear staff telling patrons that tickets are sold out for most of the day. The narrow corridors of the exhibition space are packed with people leaving smeared prints on glass as they hunch over shabtis. Children stumbling around wearing noise-cancelling headphones are enraptured by the digital guides, more than any of the objects in their physical surrounds. What is the exhibition’s overwhelming intent? Seemingly, to make money. And boy, are they making it.

Discovering Ancient Egypt,

10 Jun – 8 Oct 2023,

WA Museum Boola Bardip

Images courtesy of the WA Museum Boola Bardip’s Facebook page.

I spent several hours in the exhibition and I am still uncertain as to the actual intent (beyond the customary ambitions for a blockbuster show). The title, Discovering Ancient Egypt, is an interesting choice. Is it the audience who are “discovering”? The Dutch? The exhibition is broadly split into three categories. The first is the strongest, where it breaks down the umbrella term of “Ancient Egypt” into distinct periods. The middle section revolves around the West’s “new perspectives” on Ancient Egypt and “obsession” with Egyptology towards the later part of the twentieth century. Heavily sanitised, it reads like a PR exercise for the RMO. I do not expect the interpretation to give a dissertation-long history of issues arising from the West’s exoticisation and exploitation of Egypt, but it reads like revisionism to not even mention such facts, and instead present them as harmless fascinations. Wall space that could have explored this context is instead occupied by panels explaining how the Egyptian government gifted a statue to the Dutch royal family, or how 17th century Dutch explorers apolitically “collected” mummies to cart home to Leiden.

The final section of the exhibition relates to the Egyptian afterlife. This includes grave goods, funerary rituals, and of course, coffins and mummified human remains. As a touring exhibition, I doubt that Boola Bardip had any input into the didactic panels. What they do control is the advertising; the website features a two-sentence warning regarding the display of human remains. In contrast, the website for the National Museum of Australia (NMA)—the next institution to host the exhibition—handles the inclusion of remains not with a trigger warning, but as an opportunity for thought. “The existence of these remains prompts us all to think about profound questions relating to life and death,” the NMA’s site tells us. I wish WAM trusted their public enough to have hinted at such questions. Unfortunately, their marketing seems more invested in encouraging WA residents to “walk like an Egyptian” instead of encouraging any shred of critical thought.

I am undecided as to how I feel about human remains being displayed. It is not that I vehemently object to such displays, but I do think it is an interesting and necessary conversation to have concerning museums and their collections. This is an opportunity for the WA Museum to stimulate such dialogues. The biggest didactic in the “mummy annexe” is a panel on the x-ray process for investigating what lies beneath a mummified person’s linen bandages. The statement reassures the viewer that though “early scholars” unwrapped mummies to “study” them, now “non-invasive” scanning procedures are used. It rings like a platitude. Is keeping these bodies in their wrappings while shipping them around the world for the paying public somehow less invasive? They have already been taken from their eternal resting places, their possessions disseminated between countries, and stuck behind glass for kids to press their faces up against. The suggestion that those participating in past unwrappings were “scholars” seems misleading. The historic display of human remains is fraught with issues around respect and exploitation of the dead. Such an interpretation suggests to the public that those cutting up “mummies” were researchers doing so because the x-ray hadn’t been invented, when in fact, for many years, an industry of performative “mummy unwrappings” had been booming. Giovanni d’Athanasi, the dealer who sold the RMO their Book of the Dead of Qenna in 1835, hosted “mummy unravellings” in central London. Hundreds of punters would pack into an auditorium for hours to watch these bodies stripped, bandage by bandage. This procedure was not for research, but for public spectacle: to make money. This history was far more complex than the RMO’s exhibition would have us believe. This simplistic misrepresentation is a discursive block to understanding these historical nuances.

The decision to curate a historical exhibition so abstracted from the history it references is fascinating. To spend an hour reading about all the ways in which Ancient Egyptians would safeguard their burials—false doors, winding tombs, cartonnage coffins to prevent reuse—and then end with the display of bodies which, despite their best efforts, were turfed from their tombs, feels tone deaf, like an underhanded show of superiority. But what stays with me long after I left the exhibition is a didactic relating to the body of a mummified woman whose name is either Ta(net)kharu or Tadis. Her name was written on her coffin, but the panel informs us that “she was taken out of her coffin in the 19th century and confused with a similar looking mummy from another coffin”. This fact is presented uncritically, as if it was a common mix-up orchestrated by nobody in particular. Something that just happened. Whoops! Looking at Ta(net)kharu or Tadis I think about everything I have just learned in this very exhibition: the tiny shabtis designed to assist the dead in their afterlife, the linen amulets bearing spells to wrap around one’s body to protect those who had died, the intricate stories decorating coffins specific to that person’s life and favoured gods. Immediately prior to this room, the exhibition outlines many indicators of highly personalised funerary rituals pertaining to Ancient Egyptians. Presumably Ta(net)kharu or Tadis would have engaged in these same rituals, long before somebody came and nabbed her from her tomb and couldn’t be fucked recording her name properly. I guess they were just booting too many dead people out of their graves that day and it all got a little confusing—it happens!

Our histories are not clean. Sensibilities change. I am not expecting twenty-first century ideological purity from every archeologist or curator who came before; that line of thought is tedious and reductive. What I do want from my museum visits is to understand historical context, to be trusted with the full picture, to be encouraged to think about our past and present. The RMO, and by extension WAM, should trust their public to reflect critically on the artefacts in this exhibition. It will be interesting to see how the NMA handles these challenges. The 240 objects on display have a past, and surely to view them is more interesting when that past is contextualised? Why come to see objects in their physical form if the intent is to just snap a photo and move on, no questions asked? I was driven out of my mind while looking at the display about the Book of the Dead of Qenna, the longest written papyrus text in the RMO collection. The label states, in vague terms, that this object was chopped up into 38 pieces after being accessioned into the collection. Why was this action taken? Was this standard practice? Is chopping up manuscripts still done today, or is it frowned upon? Who knows! These vague, decontextualised statements fill the didactics throughout, and they provoke far more questions than they provide answers. We are told explicitly when the RMO has done things “correctly”, but the rest is silence.

Do these critiques matter? The exhibition is clearly a sell-out. Down at the front desk, I overhear staff telling patrons that tickets are sold out for most of the day. The narrow corridors of the exhibition space are packed with people leaving smeared prints on glass as they hunch over shabtis. Children stumbling around wearing noise-cancelling headphones are enraptured by the digital guides, more than any of the objects in their physical surrounds. What is the exhibition’s overwhelming intent? Seemingly, to make money. And boy, are they making it.

Discovering Ancient Egypt,

10 Jun – 8 Oct 2023,

WA Museum Boola Bardip

Images courtesy of the WA Museum Boola Bardip’s Facebook page.