Dispatch Review aims to pin down ideas and stir up conversations about art. We publish precise, concise art criticism, opinion pieces, interviews and audio. Dispatches are dispensed spontaneously and intended to be read in one sitting.

Editors:

Sam Beard is the head editor and co-founder of Dispatch Review. His writing has appeared in Artlink, un Magazine, and Art Collector.

Amelia Birch holds a PhD in the History of Art from the University of Western Australia, where she teaches art history.

Max Vickery is a Marxist historian and critic based in Whadjuk country. A co-founder of Dispatch Review, Vickery provides copy and line editing for texts before publication.

Jess van Heerden is an emerging arts writer and visual arts technician. They have a BA in History of Art and Fine Art, with a minor in Curatorial Studies, and are almost finished their Art History Honours.

Contributors:

Aimee Dodds is a Perth based arts writer and co-founder of Dispatch Review. She has written for Memo Review, Art Almanac, ArtsHub, and Artist Profile Magazine. Dodds has first class joint honours in the History of Art and English and Cultural Studies from the University of Western Australia.

Angus Bowskill is an artist based in Perth, WA. Their work explores observation, mediation, and redaction through digital media and printmaking techniques.

Ben Yaxley is a writer, arts student, and English teacher living in Boorloo.

Dan Glover is a barista and emerging arts writer, currently studying History of Art and Curatorial Studies at the University of Western Australia.

Darren Jorgensen lectures in art history at the University of Western Australia. His most recent book is The Dead C’s Clyma Est Mort.

Felicity Bean studies art at Murdoch University.

Francis Russell is a former academic and trade union official. He researches contemporary art and alienation, drawing on the legacies of Marxism, Freudian psychoanalysis, and phenomenology.

Ian McLean is an art historian and the former Hugh Ramsay Chair of Australian Art History at the University of Melbourne. His most recent book is Double Nation: A History of Australian Art.

Jacinta Posik studies Fine Arts and History of Art at the University of Western Australia.

Leslie Thompson is a freelance arts writer.

Kieron Broadhurst is an artist based in Perth, WA. Through a variety of media he investigates the speculative potential of fiction within contemporary art practice.

Kye Fisher holds a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Western Australia and currently works within UWA’s research portfolio. Kye has a keen interest in contemporary Chinese art and music.

Maraya Takoniatis studies and conducts research in Philosophy, Fine Arts, and History of Art at the University of Western Australia.

Matthew Taggart is an arts worker, artist and musician. Their work is experimental in its exploration of future sounds and the human experience.

Angus Bowskill is an artist based in Perth, WA. Their work explores observation, mediation, and redaction through digital media and printmaking techniques.

Ben Yaxley is a writer, arts student, and English teacher living in Boorloo.

Dan Glover is a barista and emerging arts writer, currently studying History of Art and Curatorial Studies at the University of Western Australia.

Darren Jorgensen lectures in art history at the University of Western Australia. His most recent book is The Dead C’s Clyma Est Mort.

Felicity Bean studies art at Murdoch University.

Francis Russell is a former academic and trade union official. He researches contemporary art and alienation, drawing on the legacies of Marxism, Freudian psychoanalysis, and phenomenology.

Ian McLean is an art historian and the former Hugh Ramsay Chair of Australian Art History at the University of Melbourne. His most recent book is Double Nation: A History of Australian Art.

Jacinta Posik studies Fine Arts and History of Art at the University of Western Australia.

Leslie Thompson is a freelance arts writer.

Kieron Broadhurst is an artist based in Perth, WA. Through a variety of media he investigates the speculative potential of fiction within contemporary art practice.

Kye Fisher holds a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Western Australia and currently works within UWA’s research portfolio. Kye has a keen interest in contemporary Chinese art and music.

Maraya Takoniatis studies and conducts research in Philosophy, Fine Arts, and History of Art at the University of Western Australia.

Matthew Taggart is an arts worker, artist and musician. Their work is experimental in its exploration of future sounds and the human experience.

Nalinie See holds a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in Fine Arts and Art History from The University of Western Australia. She currently works as an Art Teacher and as a Sales and Wardrobe Planning Co-worker at IKEA.

Nick FitzPatrick is an artist and arts worker. He is primarily interested in images and their relationship to systems of power and knowledge.

Rainy Colbert is an art critic and bush poet, primarily interested in the Sublime.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University and writes on Australian art.

Riley Landau is an emerging arts writer currently studying art history and curatorial studies at the University of Western Australia.

Sam Harper is an archaeologist and rock art specialist based at CRAR+M, UWA, living and working on Whadjuk country. She works with communities across the northwest of Australia.

Samuel Beilby is a contemporary artist and researcher. He currently teaches Fine Art at the University of Western Australia.

Scott Price is an artist based in Perth/Boorloo. He is interested in the interplay between culture and history in the formation of land and place relations, explored through a multidisciplinary practice.

Stirling Kain is an arts administrator with a BA in History of Art and History. She works with various arts organisations in WA.

Tara Heffernan is an art historian and critic. Her work concerns modernism and the avant-gardes, conceptual art and the lineage/s of the New Left.

Terry Smith is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, and Professor in the Division of Philosophy, Art and Critical Thought at the European Graduate School.

Zali Morgan is an emerging artist, writer and curator, currently working at The Art Gallery of Western Australia as assistant curator of Indigenous Art. She is of Ballardong, Wilman and Whadjuk descent.

Nick FitzPatrick is an artist and arts worker. He is primarily interested in images and their relationship to systems of power and knowledge.

Rainy Colbert is an art critic and bush poet, primarily interested in the Sublime.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University and writes on Australian art.

Riley Landau is an emerging arts writer currently studying art history and curatorial studies at the University of Western Australia.

Sam Harper is an archaeologist and rock art specialist based at CRAR+M, UWA, living and working on Whadjuk country. She works with communities across the northwest of Australia.

Samuel Beilby is a contemporary artist and researcher. He currently teaches Fine Art at the University of Western Australia.

Scott Price is an artist based in Perth/Boorloo. He is interested in the interplay between culture and history in the formation of land and place relations, explored through a multidisciplinary practice.

Stirling Kain is an arts administrator with a BA in History of Art and History. She works with various arts organisations in WA.

Tara Heffernan is an art historian and critic. Her work concerns modernism and the avant-gardes, conceptual art and the lineage/s of the New Left.

Terry Smith is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, and Professor in the Division of Philosophy, Art and Critical Thought at the European Graduate School.

Zali Morgan is an emerging artist, writer and curator, currently working at The Art Gallery of Western Australia as assistant curator of Indigenous Art. She is of Ballardong, Wilman and Whadjuk descent.

Note: any conflicts of interest that may arise between editors and the subject and/or topic of a review will see the affected editors forego any and all participation in the editorial process of the related text.

Designer:

Mia Davis is an arts worker and design student based in Boorloo/Perth. Davis is powered by a love of connecting audiences to art and ideas, with inclusive design being key to her practice.

Also see:

Events:

Event

Time/Date

Venue/Address

Taring Padi: Organise, Educate, Agitate!

The Modern and the Contemporary: A conversation with Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Darren Jorgensen and Peter Beilharz.

The Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth WA.

Artist as Prophet: Intersections of Art and Ritual with Robert Buratti.

Friday, 27 October, 2023,

12pm

–

12:30pm AWST

Hew Roberts Lecture Theatre, School of Design, UWA.

Virtual Reading Group sessions:

Reading

Date/Time

Sign-up

Session 5: ‘On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening’ by Theodor W. Adorno.

Tuesday, 19 Aug, 2025, 6:00pm AWST

Session 4: ‘

The Herd of Independent Minds’ by

Harold Rosenberg.

Tuesday, 15 Jul,

2025, 6:00pm AWST

Session 3:

Theory of the Avant-Garde’ by

Peter Bürger.

Tuesday, 17 Jun, 2025, 6:00pm AWST

Session 2: ‘The Originality of the Avant-Garde’ by

Rosalind E. Krauss.

Tuesday 20 May, 2025, 6:00pm AWST

Session 1: ‘Avant-Garde and Kitsch’ by Clement Greenberg.

Tuesday, 22 Apr, 2025, 6:00pm AWST

Shop:

Dispatch Review: 2024 Anthology - pre-order (due early September 2025).

The 2024 Anthology from Dispatch Review is a selection of the best art criticism from the journal's second year of publication. This anthology captures the critical conversations that shaped contemporary art in Boorloo/Perth, Western Australia during 2024. Dispatch Review is a volunteer-run journal, and proceeds from the sale of this publication will support the continuation of future anthologies. Cover design by Scott Burton.

The 2024 Anthology from Dispatch Review is a selection of the best art criticism from the journal's second year of publication. This anthology captures the critical conversations that shaped contemporary art in Boorloo/Perth, Western Australia during 2024. Dispatch Review is a volunteer-run journal, and proceeds from the sale of this publication will support the continuation of future anthologies. Cover design by Scott Burton.

Dispatch Review: 2023 Anthology

The 2023 Anthology from Dispatch Review is a selection of the best art criticism from the journal's first year of publication. Featuring texts by Sam Beard, Amelia Birch, Aimee Dodds, Max Vickery, Samuel Beilby, Tara Heffernan, Darren Jorgensen, Stirling Kain, Ian Mclean, Zali Morgan, Francis Russell, Terry Smith, Maraya Takoniatis, and Jess van Heerden, this anthology captures the critical conversations shaping contemporary art in Boorloo/Perth, Western Australia. Dispatch Review is a volunteer-run journal, and proceeds from the sale of this publication will support the continuation of future anthologies. Cover design by Scott Burton.

The 2023 Anthology from Dispatch Review is a selection of the best art criticism from the journal's first year of publication. Featuring texts by Sam Beard, Amelia Birch, Aimee Dodds, Max Vickery, Samuel Beilby, Tara Heffernan, Darren Jorgensen, Stirling Kain, Ian Mclean, Zali Morgan, Francis Russell, Terry Smith, Maraya Takoniatis, and Jess van Heerden, this anthology captures the critical conversations shaping contemporary art in Boorloo/Perth, Western Australia. Dispatch Review is a volunteer-run journal, and proceeds from the sale of this publication will support the continuation of future anthologies. Cover design by Scott Burton.

Critic’s Cup

The perfect cup for a critic. This mug will assist you in making critical judgments on art, love and life.

Click here if you would like to contact us.

This interview is published in collaboration with Guan Kan Journal. Find out more about Guan Kan here.

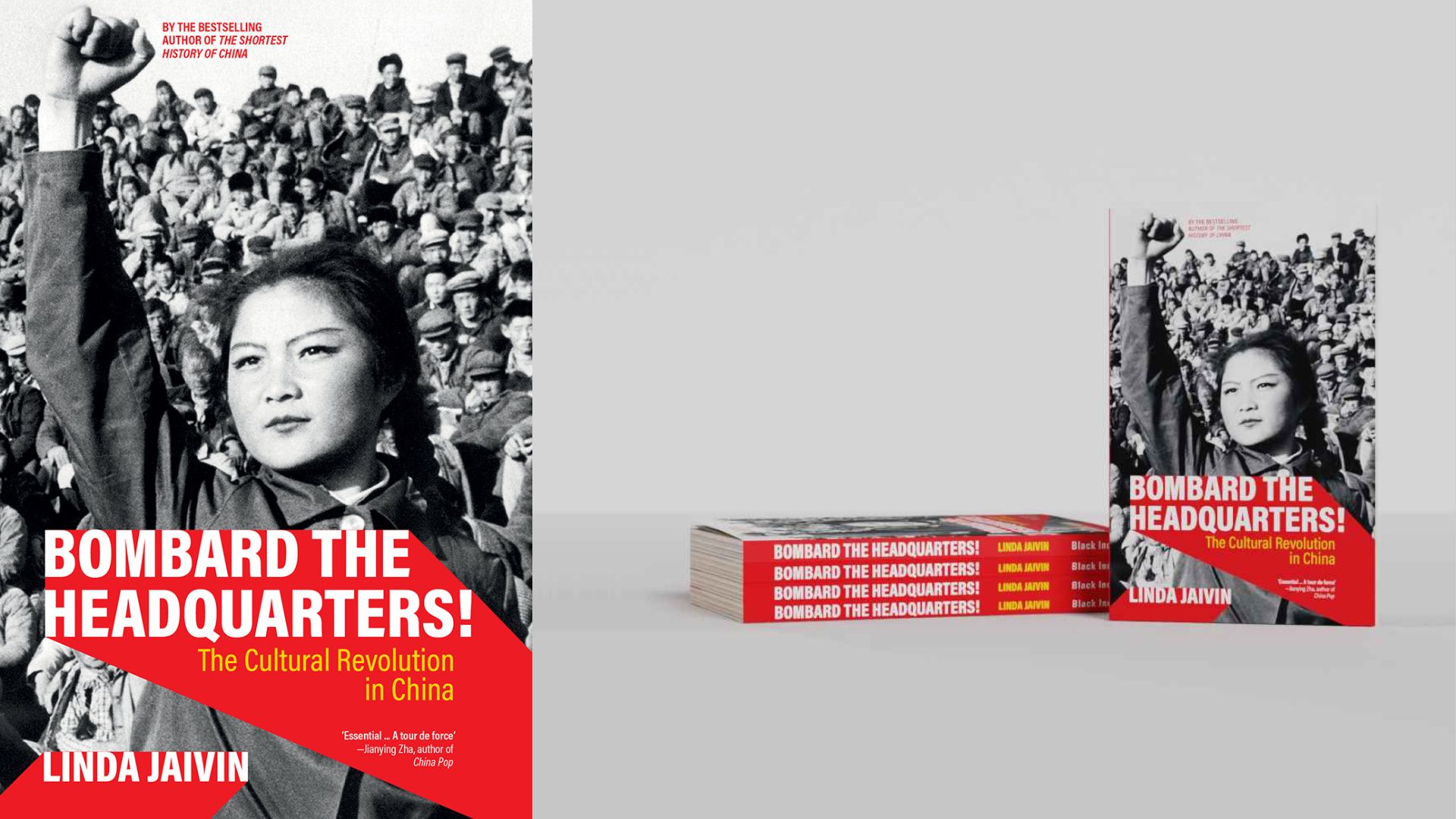

Linda Jaivin’s Bombard the Headquarters! The Cultural Revolution in China is a slim volume that tackles one of the most complex and paradoxical periods in modern Chinese history: the Cultural Revolution. The mental image that this period conjures for many of us is largely drawn from paintings of rosy cheeked workers raising their fists, stories of social turmoil, and the ideology and iconicity of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung (or “Mao’s Little Red Book”). The reality was far more nuanced, chaotic, and confusing—and in the brevity and lucid pacing of Bombard the Headquarters, the paradoxes of the Cultural Revolution, and their impact on Chinese society, emerge in stark clarity. Jaivin’s retelling of this tumultuous decade blends its key political and historical moments with vibrant details and anecdotes that are rarely included in such concise accounts.

I sat down for a video call with Linda Jaivin to discuss the book. As we set up the call, I spied a glimpse of her office—mountains of books, papers, and objects overflowing from shelves. Jaivin comments, ‘my desk is in the middle, surrounded by all this. So if we ever have an earthquake in Sydney and all of the bookshelves come down, there’ll be no finding me!’

Before we begin, I mention that I’m researching the Stars (Xing Xing) art group—a group of Beijing artists that, from around 1979–80, staged several exhibitions that broke away from Maoist social realism and championed the work of young independent artists. And of course, Linda was there! She knew many of the artists and attended Xing Xing’s first official exhibition—mounted after a famed protest show, where artworks were hung on the fence of the National Art Museum of Beijing—, reporting on the exhibition for Asiaweek in 1980. The group’s activity coincided with the Beijing Spring (1978-79), which in itself is a complex period in post-Mao history closely tied to the final stages and ultimate conclusion of the Cultural Revolution. The tangled nature of modern Chinese history, and its astounding pace, makes Bombard the Headquarters! an all the more intriguing and timely overview.

SB: … That’s something that fascinates me about the Beijing Spring, that it is often conceived of in one of two distinct ways, either as the birth of the Reform and Open Up movement or the conclusion of the earlier period. Yet, to really understand the Beijing Spring fully, both ends need to be grappled with.

LJ: Exactly. And in fact, I did struggle with that. Bombard the Headquarters! is such a short book—and it had to be. The format was set by the original UK publisher, who are putting out a whole series of very short history books. So, I had to stick to this incredibly tight format. I had so much material on the Stars; I had quotations from Bei Dao’s poetry; and I really wanted to capture the cultural life of the period. But then I thought: maybe it’s more important to show the roots of all that—how it grew out of the culture of the educated youth who were sent down to the countryside, where they began writing poetry and passing it around. And it was more important, for my story, to kind of put the weight in there.

SB: Absolutely. That was one of the first questions I had for you: in approaching the Cultural Revolution within such a slim volume, what were some of your initial considerations or approaches? What were the major themes or ideas you really wanted to grapple with?

LJ: Yeah, I thought, Gee, this is going to be very, very difficult. What I really wanted to do was cover the broad sweep of the Cultural Revolution—the big events, the narrative of it. Initially, I didn’t quite take into consideration how twisted and complicated that narrative is. It wasn’t just like: this movement, then that movement, this event, then that reaction. Everything was going on at the same time. There were so many contradictory proclamations and contradictory directives. Different campaigns were launched and then didn’t quite finish. One campaign would still be going on when another one started. It was so messy. But one of the things I did want to paint, to describe, was the overall narrative—how the Cultural Revolution unfolded.

Of course, I wanted to take into consideration some of the key players from the top—obviously Mao, Jiang Qing, and so on. I knew I would have to leave out a number of people who played important roles. However, those individuals weren’t the main movers in the end. At the same time, I wanted to be sure that I gave an impression of what was happening to ordinary people—the people being affected by these directives and campaigns. For example, you have Mao going after his political enemies, and then, at the same time, you have a translator in the Foreign Languages Bureau who’s suddenly told to stop working on a translation of an 18th-century novel. I thought: I’m going to take some peoples’ stories and weave them in to give a sense of what it was like—the real gritty details and the big sweep all in one.

I didn’t want to overemphasise the theoretical debates behind the Cultural Revolution—just to give them enough airtime so that people could understand, for example, the implications of the Bloodlines Theory [a theory used to assess individuals’ revolutionary reliability or class guilt based on family background and to determine who could join the Red Guards and who should be targeted]. There were many discussions like that, so I had to be selective. I had to go into it and say, Okay, here’s an important one.

It would have been really interesting to get into the weeds—if I’d had a huge book to fill, you know—about how some Red Guards argued for nonviolence in the very beginning of the movement. That would’ve been fascinating. But in the end, those factions lost. They lost pretty quickly. And so, they are pretty much irrelevant to the story. So, instead I mention that there was this argument between Red Guards: Do we use violence? Do we not use violence? Ultimately, it was Jiang Qing [Deputy Director of the Central Cultural Revolution Group and Mao’s wife] who conveyed messages to them that violence was acceptable.

It’s also easy to get very carried away with Mao, because he’s just riveting—he’s really, really fascinating. And he is at the centre of a lot of it. At the same time, Mao would set off these... he was the big butterfly wing that sets off all the ripples of chaos. But you can’t make it all about Mao, because it wasn’t. It was about the whole country.

I also wanted to bring in seemingly unimportant yet fascinating details. I always have this instinct, and I try to stay in touch with it when I’m writing history in particular—if there’s something that’s relatively minor, but I find interesting, I just have to trust that other people are going to find it interesting too.

For example, when I describe the birthday toast that Mao made to civil war. I could’ve dispensed with the scene by simply saying, At his birthday party, Mao toasted to civil war. But it was so much more fun to bring in Qi Benyu [a Party theorist] and have him describe the banquet, who was invited, what they were eating—because I find that interesting. So, it’s always a question of what is important? What is interesting? How do we keep the big picture, but also the little pictures, all going at once?

Along with the key Party figures, there were some dissidents—the most famous ones probably being the ones I mention, like Yu Luoke with his criticism of the Bloodlines Theory, and Zhang Zhixin—oh my god, what she went through was horrific! I made sure to include them to give an idea of the debates going on at the time. So, it’s this balancing between the general and the particular, with a real sense of the importance of keeping things really interesting.

SB: Those descriptions really stood out to me. They really add to the vibrancy of your narrative, such as your account of the incident at the British Embassy.

LJ: The British Mission, as they called it.

SB: Yes, and you describe how the staff are sitting around drinking claret, waiting as the Red Guards are protesting out front, waiting to see if they’ll storm the Mission at 10:30pm as they’ve threatened …

LJ: And watching a Peter Sellers movie! That was very funny, because I thought: Okay, there are a lot of similar incidents I could focus on––they attacked the Indonesians, they attacked many, many different people for various reasons—but with the British Mission, there was that great detail including one from the book by the American teachers Nancy and David Milton who recalled how they had seen their students walking along with cans of petrol and, at the time, thought that the students looked like they were going on a picnic! But of course, they were off to burn down the British Mission. Those accounts give such a vivid sense of just how surreal things must have felt. Then, when I started digging into it more, I found several sources saying that the British diplomats were actually watching a Peter Sellers film when the incident took place. Someone had written something like, “Wouldn’t it be great to know the name of the Peter Sellers film?” And I thought—yes, it would be!

I have an acquaintance who works at the Foreign Office in London. So, I got in touch with her. She was fantastic, and tracked down all this material, giving me a huge selection of documents. A lot of them were the diplomats’ own accounts, written after the fact for the Office’s files. And they aren’t closed files, so I was able to go through all this original material. That was really fun—even just finding out exactly what they were eating, what they were drinking. And when I discovered that the film they were watching was The Wrong Arm of the Law. I just thought, oh my god, that is so funny! So yes, it’s not the most important detail of the Cultural Revolution, obviously—but it’s such a great one.

SB: Absolutely. It really enriches things. One section that really got me thinking—towards the end—is where you begin discussing the contemporary ramifications of the Cultural Revolution. I was in China last year helping out on a student trip, and a couple of the students from WA had a really romantic idea of the Cultural Revolution. “Wouldn’t it have been amazing to live at a time when art had such a practical use?” And I just thought, wow—that’s such a romanticised reading. It really struck me. Are there any takeaways on the cultural-side of the Revolution that you hope readers might find?

LJ: I think the takeaway is that reading history carefully is terribly important. Even in China, there are young people who are romanticising the Cultural Revolution. It’s easy to get caught up in the romantic ideal of such movements—but only if you underplay its violence. And if the goal is some kind of revolutionary purity, as it was then, then the implications go well beyond the field of culture. I think people just need to read more history generally. Because it is very easy to make generalisations about history that are not only unhelpful for your own understanding, but also for how you approach politics and society more broadly. It’s interesting because my generation did the same thing. It was like, “Oh, the Cultural Revolution, isn’t it wonderful?” Completely misunderstanding it. Some students now might think, “well, culture got a lot of prominence,” and so on. And of course, we are living in this hyper-capitalist society where culture is just another product, which, I agree, is a terrible thing. But what you also have to understand—if you’re going to take the Cultural Revolution as any kind of ideal—is that artists and writers at the time couldn’t deviate one little bit from the political message. Those who did so got into trouble. Take the revolutionary model operas for example. The model operas were constructed so that if one was performed in one city and in a city hundreds of kilometres away, the patches on the peasants’ clothing would have to be in exactly the same place. There was no room for creativity. They were “models” in the industrial sense—something you make for replication. The replication had to be precise. And the other thing to understand about revolutionary culture—Cultural Revolutionary culture in particular—is that there is no ambiguity. There is no room for grey characters, doubters, oddballs, only villains, or heroes. They might have some sort of revelation or whatever, but there isn’t complexity. So, obviously, you couldn’t capture humanity. Because humanity is enormously complex. And really good art captures that ambiguity. You couldn’t have it.

SB: Oh, that’s such an interesting point. Another thing that really stood out to me in your account is how much the readings of Mao’s texts—which might have seemed black and white on the surface—inevitably led to so much misreading. The interpretation and misinterpretation really fuelled the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.

LJ: Mao’s pronouncements could become quite oracular. A lot of his writing—things like On Contradiction, and so on—offers broad principles on which to act, and the interpretation is left up to the individual. But in China, you really shouldn’t get that interpretation wrong. Still today, the Communist Party operates more or less on this principle. You’ll often hear people talk about a jīngshén (or ‘spirit’, the ideological intent of a directive) that has come down from above. For example, the central government generally won’t issue a specific directive to the media—like “you should write about feminism this way, and not that way.” Instead, there will be a general jīngshén that talks about values, or the need for a certain kind of social guidance. Everyone at the lower levels has to try to figure out what that jīngshén actually means for them and sweat buckets in the process. Because, if they get it wrong, they get punished. That is why you often see self-censorship in China. It is much easier not to do something than to take a chance, stick your neck out. And during the Cultural Revolution, that principle was in operation but on steroids. There is just no way you would want to do anything that contradicted one of Mao’s pronouncements.

SB: This is more of a question on style. You have a real knack for wit in your writing, which is quite consistent across the work of yours that I have read. I’m curious about your use of wit when writing history. It’s an interesting pairing and an enjoyable aspect of the book!

LJ: Thank you. I think I tend to see the odd side of things. I tend to notice where things bump up against each other in strange ways. So, it’s just instinct, I think. For example, when I was at the Sydney Writers Festival in May, I was on a panel. The person leading the panel asked, “What is the difference, in your opinion, between Mao’s personality cult and Xi’s personality cult?” And the answer that just popped into my head was: “Mao had a personality!” But in fact, that actually says a lot. Because Xi’s personality cult is a construct. It’s a very carefully managed construct. Mao’s personality cult was a construct too, but it took root in society because he was a genuine revolutionary hero. To the people of China, Mao had a real legacy. They knew he had been on the Long March, they knew he had fought, that he had been through all that. He declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China from Tiananmen. So, even though he had done some pretty shitty things—the Great Leap Forward and so on—if the goal is to create a personality cult and amplify that sense of gratitude and make a leader into even more of a god, it’s easier when you’ve got that kind of background. Whereas Xi Jinping was the son of a persecuted official, who went to the countryside like everybody else and worked his way up—obviously with a bit of help from the family name. Xi did the hard yards of being the head of this district and that province. But it’s not such an awe-inspiring story.

SB: It’s much more of a bureaucrat’s journey, isn’t it?

LJ: Yes, it’s a bureaucrat’s journey, and Mao’s was a hero’s journey. Of course, Mao’s was exaggerated in many ways. I have a slide in one of the talks I give—it shows a very famous painting of Mao at the founding of the party in 1921. He’s standing up, orating, and people are looking up at him. That’s completely ridiculous. He was a very young party member. One of the youngest, if not the youngest. He wouldn’t have been the one standing up and declaiming while everybody listened. But he was at the meeting where the Communist Party was founded. So basically, it’s a cult that’s been developed, but it’s based on real events. He was one of the founding members. By the time we get to the Cultural Revolution, the young people really did see him as a hero. The reason that’s important in the Cultural Revolution is that he was able to mobilise people based on their belief in him—the young people thought he was in trouble and swore to protect him with their lives, calling themselves Red Guards. That’s pretty amazing, right? Can you imagine a group of people on a campus today getting together and so dramatically vowing to protect Xi Jinping? It’s just very different.

SB: Yeah, absolutely. You touch on that at the end of the book, where you describe this new kind of nationalism and rose-tinted desire to go back to the Revolution. It made me think of “Make America Great Again” and other manifestations of that kind of nostalgia—the intersection of nationalism and nostalgia.

LJ: It’s very interesting. I’ve written and spoken about this, about how Trump operates by keeping everyone around him nervous, like Mao did. One moment, someone is in his favour, then they’re not. And not being in his favour is actually quite a punishment. The way Mao could just switch, and suddenly everybody else was left flat-footed. Trump does the same. Mao demanded absolute loyalty, and so does Trump. There’s a lot of comparisons to be made. One of the lectures I’ve given a couple of times is Bombard the Headquarters: From Mao to Musk. Attacking the “deep state” is very much what Mao was doing. His version of the deep state was revisionism—where things get static and the revolution stops, and it falls victim to bureaucratisation, corruption, and everything else that characterises the ‘deep state’.

Then there’s the whole thing about mass dictatorship. Mao was inspired by what was called the Maple Bridge experience. Basically, the idea is that it’s dictatorship over the masses by the masses themselves. The ‘masses’ police each other; they dob each other in, and in some cases, they bring them to justice. That reached its apotheosis during the Cultural Revolution, where the mob was the accuser, the interrogator, and the punisher. That was mass dictatorship. When Elon Musk knew he would be in charge of DOGE, there were people on X identifying various “woke” departments or jobs in the public service, including individual staff members, a lot of them women, calling for their sacking. These posts were amplified by Musk to all his followers, and many of them responded by sending these people death threats, rape threats, etc. That, to me, follows the model of mass dictatorship. I do not think you can say Trump equals Mao, or Mao equals Trump. However, it is very useful to look at parallels, and there are plenty!

SB: Oh, that's so interesting.

LJ: I mean, the big difference is that Trump stands for nothing except himself and his ability—and his family’s ability—to grift. But Mao cared about the revolution. He did have principles. He did have a goal that was bigger than himself. Now, that doesn’t excuse what happened. But when thinking about the parallels, you have to note that Trump stands for nothing, and Mao stood for something.

SB: With that in mind, are there any myths or common misconceptions about the Cultural Revolution which you hope to have challenged or corrected with Bombard the Headquarters?

LJ: That's an interesting question. I think one of the myths I hope the book dispels is that the Cultural Revolution was entirely directed from the top. Mao and Jiang Qing. The other is that it was entirely carried out from the bottom. The Red Guards. The reality lies in the complex dance between those two forces. You can see this in moments like Mao telling the youth, “Rebellion is justified,” while Zhou Enlai follows up with, “Yes, but only according to directions from the top.” Another thing I hope readers reflect on is how easy it is, including in contemporary Western societies, to get swept up in movements that promise clear answers to big questions. But those big questions rarely have black-and-white answers. The Cultural Revolution was full of conspiracy theories, one after another. It’s important to see how people can get caught up in that kind of thinking. I also hope readers think about the many Red Guards who later regretted what they did, or who at least reflected critically on their actions. With hindsight, we can begin to understand the dangers of mass movements, of ideological fervour, and of acting without deeply questioning why we believe what we do. Young people in Australia today have access to so much more information than the Red Guards ever did. That doesn’t mean we're immune to manipulation—but it does mean we have the opportunity to be more critical, more resistant, and more thoughtful in the face of it. And that ‘it’ could be, you know, anything from evangelical Christian cults to QAnon!

SB: Thanks again for speaking with me—one last question, and a sort of cheeky one! I’ve read several of your other books, recently including Confessions of an S&M Virgin. In the introduction of that collection of essays, you reflect on your move from more journalistic work about China to writing fiction, saying that: “For me, the movement from journalism to fiction seemed inevitable. Whatever I have worked on, it has been people who have interested me the most.” Now that you’ve moved from fiction back to writing about Chinese history, I wonder, what reflections do you have on the two modes of writing and your work looking back.

LJ: I think I’m still mainly interested in people, which informs the way that I write history. But yeah, fiction is incredibly hard. I think I did get better at it as time went on. Some of the earlier work makes me cringe a little bit! I tried very hard to write a (third) novel set in China. I worked on it from the late 1980s until about four years ago. I kept putting it aside, then picking it up again. And in the end—it just wasn’t working. I finally showed it to my agent and my publisher, and they were like, “Yeah, it’s not really working.” And I said, “I know. I just don’t know how to make it work.” So, I thought, okay, let me focus on non-fiction for a while. I’m now working on The Shortest History of Madrid. I love the format of writing short histories! I do have an idea for another novel though!

Linda Jaivin’s Bombard the Headquarters! The Cultural Revolution in China is a slim volume that tackles one of the most complex and paradoxical periods in modern Chinese history: the Cultural Revolution. The mental image that this period conjures for many of us is largely drawn from paintings of rosy cheeked workers raising their fists, stories of social turmoil, and the ideology and iconicity of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung (or “Mao’s Little Red Book”). The reality was far more nuanced, chaotic, and confusing—and in the brevity and lucid pacing of Bombard the Headquarters, the paradoxes of the Cultural Revolution, and their impact on Chinese society, emerge in stark clarity. Jaivin’s retelling of this tumultuous decade blends its key political and historical moments with vibrant details and anecdotes that are rarely included in such concise accounts.

I sat down for a video call with Linda Jaivin to discuss the book. As we set up the call, I spied a glimpse of her office—mountains of books, papers, and objects overflowing from shelves. Jaivin comments, ‘my desk is in the middle, surrounded by all this. So if we ever have an earthquake in Sydney and all of the bookshelves come down, there’ll be no finding me!’

Before we begin, I mention that I’m researching the Stars (Xing Xing) art group—a group of Beijing artists that, from around 1979–80, staged several exhibitions that broke away from Maoist social realism and championed the work of young independent artists. And of course, Linda was there! She knew many of the artists and attended Xing Xing’s first official exhibition—mounted after a famed protest show, where artworks were hung on the fence of the National Art Museum of Beijing—, reporting on the exhibition for Asiaweek in 1980. The group’s activity coincided with the Beijing Spring (1978-79), which in itself is a complex period in post-Mao history closely tied to the final stages and ultimate conclusion of the Cultural Revolution. The tangled nature of modern Chinese history, and its astounding pace, makes Bombard the Headquarters! an all the more intriguing and timely overview.

SB: … That’s something that fascinates me about the Beijing Spring, that it is often conceived of in one of two distinct ways, either as the birth of the Reform and Open Up movement or the conclusion of the earlier period. Yet, to really understand the Beijing Spring fully, both ends need to be grappled with.

LJ: Exactly. And in fact, I did struggle with that. Bombard the Headquarters! is such a short book—and it had to be. The format was set by the original UK publisher, who are putting out a whole series of very short history books. So, I had to stick to this incredibly tight format. I had so much material on the Stars; I had quotations from Bei Dao’s poetry; and I really wanted to capture the cultural life of the period. But then I thought: maybe it’s more important to show the roots of all that—how it grew out of the culture of the educated youth who were sent down to the countryside, where they began writing poetry and passing it around. And it was more important, for my story, to kind of put the weight in there.

SB: Absolutely. That was one of the first questions I had for you: in approaching the Cultural Revolution within such a slim volume, what were some of your initial considerations or approaches? What were the major themes or ideas you really wanted to grapple with?

LJ: Yeah, I thought, Gee, this is going to be very, very difficult. What I really wanted to do was cover the broad sweep of the Cultural Revolution—the big events, the narrative of it. Initially, I didn’t quite take into consideration how twisted and complicated that narrative is. It wasn’t just like: this movement, then that movement, this event, then that reaction. Everything was going on at the same time. There were so many contradictory proclamations and contradictory directives. Different campaigns were launched and then didn’t quite finish. One campaign would still be going on when another one started. It was so messy. But one of the things I did want to paint, to describe, was the overall narrative—how the Cultural Revolution unfolded.

Of course, I wanted to take into consideration some of the key players from the top—obviously Mao, Jiang Qing, and so on. I knew I would have to leave out a number of people who played important roles. However, those individuals weren’t the main movers in the end. At the same time, I wanted to be sure that I gave an impression of what was happening to ordinary people—the people being affected by these directives and campaigns. For example, you have Mao going after his political enemies, and then, at the same time, you have a translator in the Foreign Languages Bureau who’s suddenly told to stop working on a translation of an 18th-century novel. I thought: I’m going to take some peoples’ stories and weave them in to give a sense of what it was like—the real gritty details and the big sweep all in one.

I didn’t want to overemphasise the theoretical debates behind the Cultural Revolution—just to give them enough airtime so that people could understand, for example, the implications of the Bloodlines Theory [a theory used to assess individuals’ revolutionary reliability or class guilt based on family background and to determine who could join the Red Guards and who should be targeted]. There were many discussions like that, so I had to be selective. I had to go into it and say, Okay, here’s an important one.

It would have been really interesting to get into the weeds—if I’d had a huge book to fill, you know—about how some Red Guards argued for nonviolence in the very beginning of the movement. That would’ve been fascinating. But in the end, those factions lost. They lost pretty quickly. And so, they are pretty much irrelevant to the story. So, instead I mention that there was this argument between Red Guards: Do we use violence? Do we not use violence? Ultimately, it was Jiang Qing [Deputy Director of the Central Cultural Revolution Group and Mao’s wife] who conveyed messages to them that violence was acceptable.

It’s also easy to get very carried away with Mao, because he’s just riveting—he’s really, really fascinating. And he is at the centre of a lot of it. At the same time, Mao would set off these... he was the big butterfly wing that sets off all the ripples of chaos. But you can’t make it all about Mao, because it wasn’t. It was about the whole country.

I also wanted to bring in seemingly unimportant yet fascinating details. I always have this instinct, and I try to stay in touch with it when I’m writing history in particular—if there’s something that’s relatively minor, but I find interesting, I just have to trust that other people are going to find it interesting too.

For example, when I describe the birthday toast that Mao made to civil war. I could’ve dispensed with the scene by simply saying, At his birthday party, Mao toasted to civil war. But it was so much more fun to bring in Qi Benyu [a Party theorist] and have him describe the banquet, who was invited, what they were eating—because I find that interesting. So, it’s always a question of what is important? What is interesting? How do we keep the big picture, but also the little pictures, all going at once?

Along with the key Party figures, there were some dissidents—the most famous ones probably being the ones I mention, like Yu Luoke with his criticism of the Bloodlines Theory, and Zhang Zhixin—oh my god, what she went through was horrific! I made sure to include them to give an idea of the debates going on at the time. So, it’s this balancing between the general and the particular, with a real sense of the importance of keeping things really interesting.

SB: Those descriptions really stood out to me. They really add to the vibrancy of your narrative, such as your account of the incident at the British Embassy.

LJ: The British Mission, as they called it.

SB: Yes, and you describe how the staff are sitting around drinking claret, waiting as the Red Guards are protesting out front, waiting to see if they’ll storm the Mission at 10:30pm as they’ve threatened …

LJ: And watching a Peter Sellers movie! That was very funny, because I thought: Okay, there are a lot of similar incidents I could focus on––they attacked the Indonesians, they attacked many, many different people for various reasons—but with the British Mission, there was that great detail including one from the book by the American teachers Nancy and David Milton who recalled how they had seen their students walking along with cans of petrol and, at the time, thought that the students looked like they were going on a picnic! But of course, they were off to burn down the British Mission. Those accounts give such a vivid sense of just how surreal things must have felt. Then, when I started digging into it more, I found several sources saying that the British diplomats were actually watching a Peter Sellers film when the incident took place. Someone had written something like, “Wouldn’t it be great to know the name of the Peter Sellers film?” And I thought—yes, it would be!

I have an acquaintance who works at the Foreign Office in London. So, I got in touch with her. She was fantastic, and tracked down all this material, giving me a huge selection of documents. A lot of them were the diplomats’ own accounts, written after the fact for the Office’s files. And they aren’t closed files, so I was able to go through all this original material. That was really fun—even just finding out exactly what they were eating, what they were drinking. And when I discovered that the film they were watching was The Wrong Arm of the Law. I just thought, oh my god, that is so funny! So yes, it’s not the most important detail of the Cultural Revolution, obviously—but it’s such a great one.

SB: Absolutely. It really enriches things. One section that really got me thinking—towards the end—is where you begin discussing the contemporary ramifications of the Cultural Revolution. I was in China last year helping out on a student trip, and a couple of the students from WA had a really romantic idea of the Cultural Revolution. “Wouldn’t it have been amazing to live at a time when art had such a practical use?” And I just thought, wow—that’s such a romanticised reading. It really struck me. Are there any takeaways on the cultural-side of the Revolution that you hope readers might find?

LJ: I think the takeaway is that reading history carefully is terribly important. Even in China, there are young people who are romanticising the Cultural Revolution. It’s easy to get caught up in the romantic ideal of such movements—but only if you underplay its violence. And if the goal is some kind of revolutionary purity, as it was then, then the implications go well beyond the field of culture. I think people just need to read more history generally. Because it is very easy to make generalisations about history that are not only unhelpful for your own understanding, but also for how you approach politics and society more broadly. It’s interesting because my generation did the same thing. It was like, “Oh, the Cultural Revolution, isn’t it wonderful?” Completely misunderstanding it. Some students now might think, “well, culture got a lot of prominence,” and so on. And of course, we are living in this hyper-capitalist society where culture is just another product, which, I agree, is a terrible thing. But what you also have to understand—if you’re going to take the Cultural Revolution as any kind of ideal—is that artists and writers at the time couldn’t deviate one little bit from the political message. Those who did so got into trouble. Take the revolutionary model operas for example. The model operas were constructed so that if one was performed in one city and in a city hundreds of kilometres away, the patches on the peasants’ clothing would have to be in exactly the same place. There was no room for creativity. They were “models” in the industrial sense—something you make for replication. The replication had to be precise. And the other thing to understand about revolutionary culture—Cultural Revolutionary culture in particular—is that there is no ambiguity. There is no room for grey characters, doubters, oddballs, only villains, or heroes. They might have some sort of revelation or whatever, but there isn’t complexity. So, obviously, you couldn’t capture humanity. Because humanity is enormously complex. And really good art captures that ambiguity. You couldn’t have it.

SB: Oh, that’s such an interesting point. Another thing that really stood out to me in your account is how much the readings of Mao’s texts—which might have seemed black and white on the surface—inevitably led to so much misreading. The interpretation and misinterpretation really fuelled the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.

LJ: Mao’s pronouncements could become quite oracular. A lot of his writing—things like On Contradiction, and so on—offers broad principles on which to act, and the interpretation is left up to the individual. But in China, you really shouldn’t get that interpretation wrong. Still today, the Communist Party operates more or less on this principle. You’ll often hear people talk about a jīngshén (or ‘spirit’, the ideological intent of a directive) that has come down from above. For example, the central government generally won’t issue a specific directive to the media—like “you should write about feminism this way, and not that way.” Instead, there will be a general jīngshén that talks about values, or the need for a certain kind of social guidance. Everyone at the lower levels has to try to figure out what that jīngshén actually means for them and sweat buckets in the process. Because, if they get it wrong, they get punished. That is why you often see self-censorship in China. It is much easier not to do something than to take a chance, stick your neck out. And during the Cultural Revolution, that principle was in operation but on steroids. There is just no way you would want to do anything that contradicted one of Mao’s pronouncements.

SB: This is more of a question on style. You have a real knack for wit in your writing, which is quite consistent across the work of yours that I have read. I’m curious about your use of wit when writing history. It’s an interesting pairing and an enjoyable aspect of the book!

LJ: Thank you. I think I tend to see the odd side of things. I tend to notice where things bump up against each other in strange ways. So, it’s just instinct, I think. For example, when I was at the Sydney Writers Festival in May, I was on a panel. The person leading the panel asked, “What is the difference, in your opinion, between Mao’s personality cult and Xi’s personality cult?” And the answer that just popped into my head was: “Mao had a personality!” But in fact, that actually says a lot. Because Xi’s personality cult is a construct. It’s a very carefully managed construct. Mao’s personality cult was a construct too, but it took root in society because he was a genuine revolutionary hero. To the people of China, Mao had a real legacy. They knew he had been on the Long March, they knew he had fought, that he had been through all that. He declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China from Tiananmen. So, even though he had done some pretty shitty things—the Great Leap Forward and so on—if the goal is to create a personality cult and amplify that sense of gratitude and make a leader into even more of a god, it’s easier when you’ve got that kind of background. Whereas Xi Jinping was the son of a persecuted official, who went to the countryside like everybody else and worked his way up—obviously with a bit of help from the family name. Xi did the hard yards of being the head of this district and that province. But it’s not such an awe-inspiring story.

SB: It’s much more of a bureaucrat’s journey, isn’t it?

LJ: Yes, it’s a bureaucrat’s journey, and Mao’s was a hero’s journey. Of course, Mao’s was exaggerated in many ways. I have a slide in one of the talks I give—it shows a very famous painting of Mao at the founding of the party in 1921. He’s standing up, orating, and people are looking up at him. That’s completely ridiculous. He was a very young party member. One of the youngest, if not the youngest. He wouldn’t have been the one standing up and declaiming while everybody listened. But he was at the meeting where the Communist Party was founded. So basically, it’s a cult that’s been developed, but it’s based on real events. He was one of the founding members. By the time we get to the Cultural Revolution, the young people really did see him as a hero. The reason that’s important in the Cultural Revolution is that he was able to mobilise people based on their belief in him—the young people thought he was in trouble and swore to protect him with their lives, calling themselves Red Guards. That’s pretty amazing, right? Can you imagine a group of people on a campus today getting together and so dramatically vowing to protect Xi Jinping? It’s just very different.

SB: Yeah, absolutely. You touch on that at the end of the book, where you describe this new kind of nationalism and rose-tinted desire to go back to the Revolution. It made me think of “Make America Great Again” and other manifestations of that kind of nostalgia—the intersection of nationalism and nostalgia.

LJ: It’s very interesting. I’ve written and spoken about this, about how Trump operates by keeping everyone around him nervous, like Mao did. One moment, someone is in his favour, then they’re not. And not being in his favour is actually quite a punishment. The way Mao could just switch, and suddenly everybody else was left flat-footed. Trump does the same. Mao demanded absolute loyalty, and so does Trump. There’s a lot of comparisons to be made. One of the lectures I’ve given a couple of times is Bombard the Headquarters: From Mao to Musk. Attacking the “deep state” is very much what Mao was doing. His version of the deep state was revisionism—where things get static and the revolution stops, and it falls victim to bureaucratisation, corruption, and everything else that characterises the ‘deep state’.

Then there’s the whole thing about mass dictatorship. Mao was inspired by what was called the Maple Bridge experience. Basically, the idea is that it’s dictatorship over the masses by the masses themselves. The ‘masses’ police each other; they dob each other in, and in some cases, they bring them to justice. That reached its apotheosis during the Cultural Revolution, where the mob was the accuser, the interrogator, and the punisher. That was mass dictatorship. When Elon Musk knew he would be in charge of DOGE, there were people on X identifying various “woke” departments or jobs in the public service, including individual staff members, a lot of them women, calling for their sacking. These posts were amplified by Musk to all his followers, and many of them responded by sending these people death threats, rape threats, etc. That, to me, follows the model of mass dictatorship. I do not think you can say Trump equals Mao, or Mao equals Trump. However, it is very useful to look at parallels, and there are plenty!

SB: Oh, that's so interesting.

LJ: I mean, the big difference is that Trump stands for nothing except himself and his ability—and his family’s ability—to grift. But Mao cared about the revolution. He did have principles. He did have a goal that was bigger than himself. Now, that doesn’t excuse what happened. But when thinking about the parallels, you have to note that Trump stands for nothing, and Mao stood for something.

SB: With that in mind, are there any myths or common misconceptions about the Cultural Revolution which you hope to have challenged or corrected with Bombard the Headquarters?

LJ: That's an interesting question. I think one of the myths I hope the book dispels is that the Cultural Revolution was entirely directed from the top. Mao and Jiang Qing. The other is that it was entirely carried out from the bottom. The Red Guards. The reality lies in the complex dance between those two forces. You can see this in moments like Mao telling the youth, “Rebellion is justified,” while Zhou Enlai follows up with, “Yes, but only according to directions from the top.” Another thing I hope readers reflect on is how easy it is, including in contemporary Western societies, to get swept up in movements that promise clear answers to big questions. But those big questions rarely have black-and-white answers. The Cultural Revolution was full of conspiracy theories, one after another. It’s important to see how people can get caught up in that kind of thinking. I also hope readers think about the many Red Guards who later regretted what they did, or who at least reflected critically on their actions. With hindsight, we can begin to understand the dangers of mass movements, of ideological fervour, and of acting without deeply questioning why we believe what we do. Young people in Australia today have access to so much more information than the Red Guards ever did. That doesn’t mean we're immune to manipulation—but it does mean we have the opportunity to be more critical, more resistant, and more thoughtful in the face of it. And that ‘it’ could be, you know, anything from evangelical Christian cults to QAnon!

SB: Thanks again for speaking with me—one last question, and a sort of cheeky one! I’ve read several of your other books, recently including Confessions of an S&M Virgin. In the introduction of that collection of essays, you reflect on your move from more journalistic work about China to writing fiction, saying that: “For me, the movement from journalism to fiction seemed inevitable. Whatever I have worked on, it has been people who have interested me the most.” Now that you’ve moved from fiction back to writing about Chinese history, I wonder, what reflections do you have on the two modes of writing and your work looking back.

LJ: I think I’m still mainly interested in people, which informs the way that I write history. But yeah, fiction is incredibly hard. I think I did get better at it as time went on. Some of the earlier work makes me cringe a little bit! I tried very hard to write a (third) novel set in China. I worked on it from the late 1980s until about four years ago. I kept putting it aside, then picking it up again. And in the end—it just wasn’t working. I finally showed it to my agent and my publisher, and they were like, “Yeah, it’s not really working.” And I said, “I know. I just don’t know how to make it work.” So, I thought, okay, let me focus on non-fiction for a while. I’m now working on The Shortest History of Madrid. I love the format of writing short histories! I do have an idea for another novel though!

Hatched Dispatched 2025

Saturday, 23 August 2025

The 2025 Hatched exhibition is by far the most spacious iteration of the national graduate exhibition, having been relocated into a temporary venue in Forrest Chase while renovations take place at PICA. Five critics visited the exhibition, and offer their insights here on

the particular works they were drawn to. For

Nalinie

See and Kye Fisher, Grace Yong’s 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology) prompted two

divergent responses to one of the central aspects of the work. Jess van Heerden

examines the pastels of Silki Wong’s Grip and skatepark iconography of Nicole Goode’s Linger. Maraya Takoniatis offers a close reading of Germaine Chan’s

painting It’s the Revelation along

with some reflections on the upward trajectory of the exhibition from last

year. Riley Landau reflects on the innovative methods of image-making used by Litia

Roko and Pippini Niamh, whose respective uses of digital media and printmaking break from expectations. The 2025 Dr Harold Schenberg Arts

award winners include Samuel Chan for his sculptures, of which Transfiguration is among his most

impressive, Tom Duffy’s thought-provoking (yet, to my mind, somewhat unresolved) paintings Djagats (The Newly Arrived/Native Dignity),

and Grace Yong’s pensive video 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology). Artworks by a

further 20 graduates are included in this year’s exhibition, which runs until 5

October 2025—and with the following thoughts of these critics in mind, I will

certainly be revisiting before then.

![]()

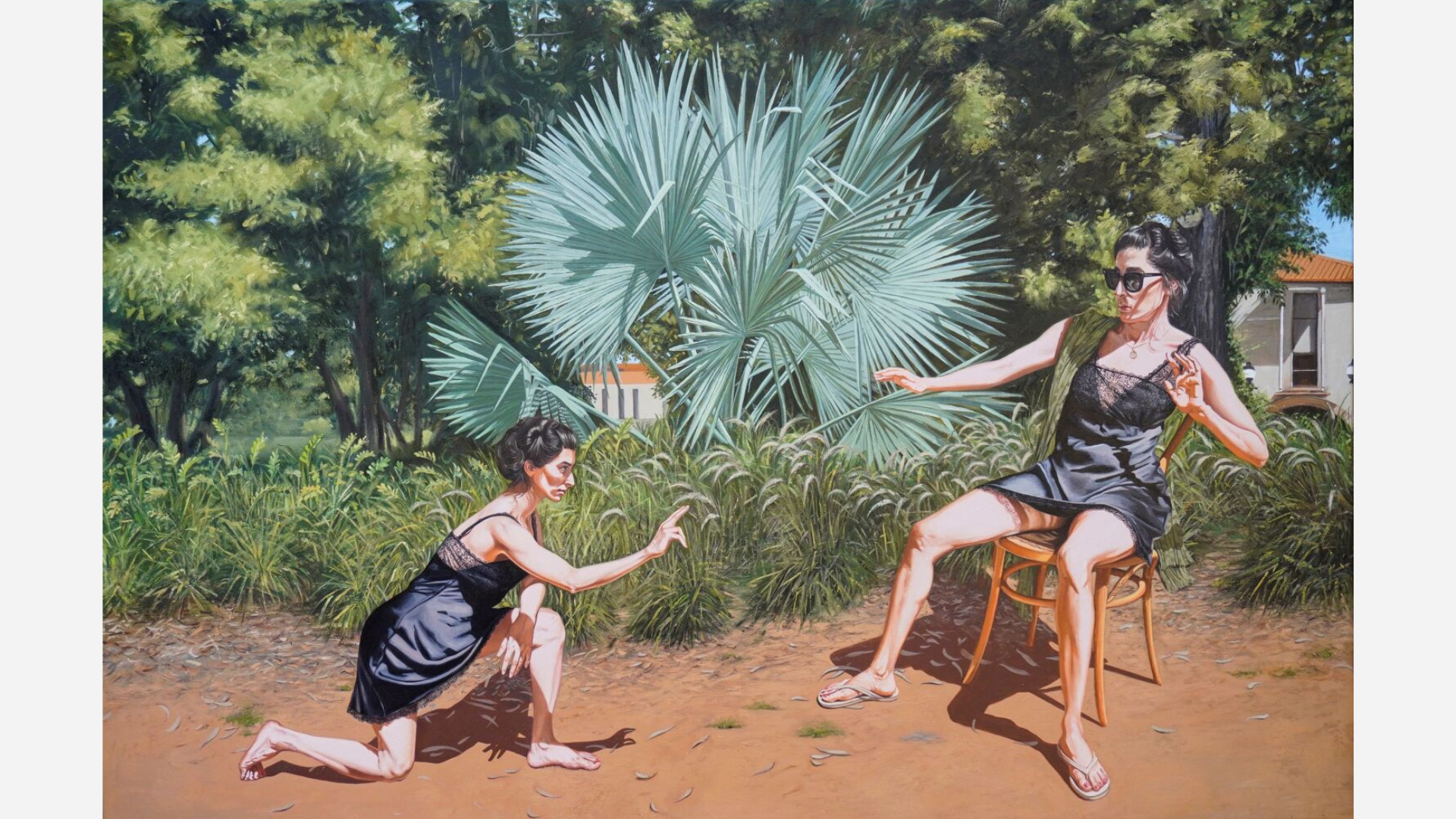

Germaine Chan, It’s the Revelation

The jumble of exposed beams, air vents, and modern skylights in PICA’s Forrest Chase venue for Hatched 2025 unexpectedly elevated the annual graduate show. Finally, young artists were placed in a room that reflected the world their generation experiences: gritty, exposed and over-engineered. The context of this fresh venue gave the works greater relevance and timeliness, even though overall there was a strong material and conceptual adherence to the previous iterations of the exhibition—after all, the arts students may change, but the art educations they receive year after year primarily remain the same. One surprising development was the selection of a contemporary painting from UWA, whose Hatched contributions in recent years have evidenced a preference for students embracing less-traditional mediums (in contrast with Curtin, which routinely champions its graduating painters). UWA student and mixed media artist Germaine Chan’s contribution to Hatched, It’s the Revelation, revives historical religious painting for a contemporary context. Across her panoramic scenes, Chan’s assorted fragments of morally dubious stick-figures in ugly, human gesticulations offer a discursive reflection on contemporary inter-personal entanglements. But Chan’s genius is not in the story she tells. The real highlight of It’s the Revelation is that despite sharing with almost every other work at Hatched the feature of visually ambiguous composition, it engages this contemporary convention without compromising Chan’s idiosyncratic expression and singular artistic identity. It is this kind of artistic innovation, of using ubiquitous and stale tools to solidify one’s distinctive artistic identity, that sees Chan carving out a space for herself within—what usually feels like—a cyclical contemporary artworld. Chan’s repackaging of a ubiquitous way of working resonates with Hatched 2025, which is itself an unironic attempt to restyle the old, improving it, whilst bypassing the struggle of starting from scratch. These innovations prove that consistency does not require conformity and that Hatched may still have more to give us.

![]()

Litia Roko, 500mL/point

In today’s world, it’s a Sisyphean task to locate an artist who hasn’t been affected by the rise of generative artificial intelligence. A society already inundated with a crippling inability to engage in arts, now believes that meaningful images can be produced by an algorithm regurgitating probabilistic pixels and slop. It is no surprise a collective exhibition of recently graduated and emerging artists would grapple with this existential challenge. Litia Roko’s work 500 mL/point satirises this looming challenge to art practices by presenting her own cost benefit analysis of using AI. The name itself refers to the drastic water usage AI servers require to prevent themselves from combusting. The most resonant area of her video was the open criticism of the Living Museum App. This supposedly pedagogical resource claims to use AI to bring objects from the British Museum to life. The ethical authority of western programs—notorious for their wealth of stolen heritage—is already obviously problematic, yet Roko’s video intensifies the distressing qualities of rampant AI, reflecting its true scale. She draws attention to the ways that algorithms privilege the information they have been fed, and how this can be weaponised to produce narratives that obscure and mystify the truth. For instance, in 500mL/point a Moai head claims, “I love it here,” though of course it can only speak with what data it has been fed. By so openly confronting the issues that arise when artistic practice melds with generative machinery, Roko’s work leaves any viewer more assured of the absolute inherent and indispensable worth of the human element in artistic and academic practices.

![]()

Nicole Goode, Linger (grind rail) and Linger (break ramp)

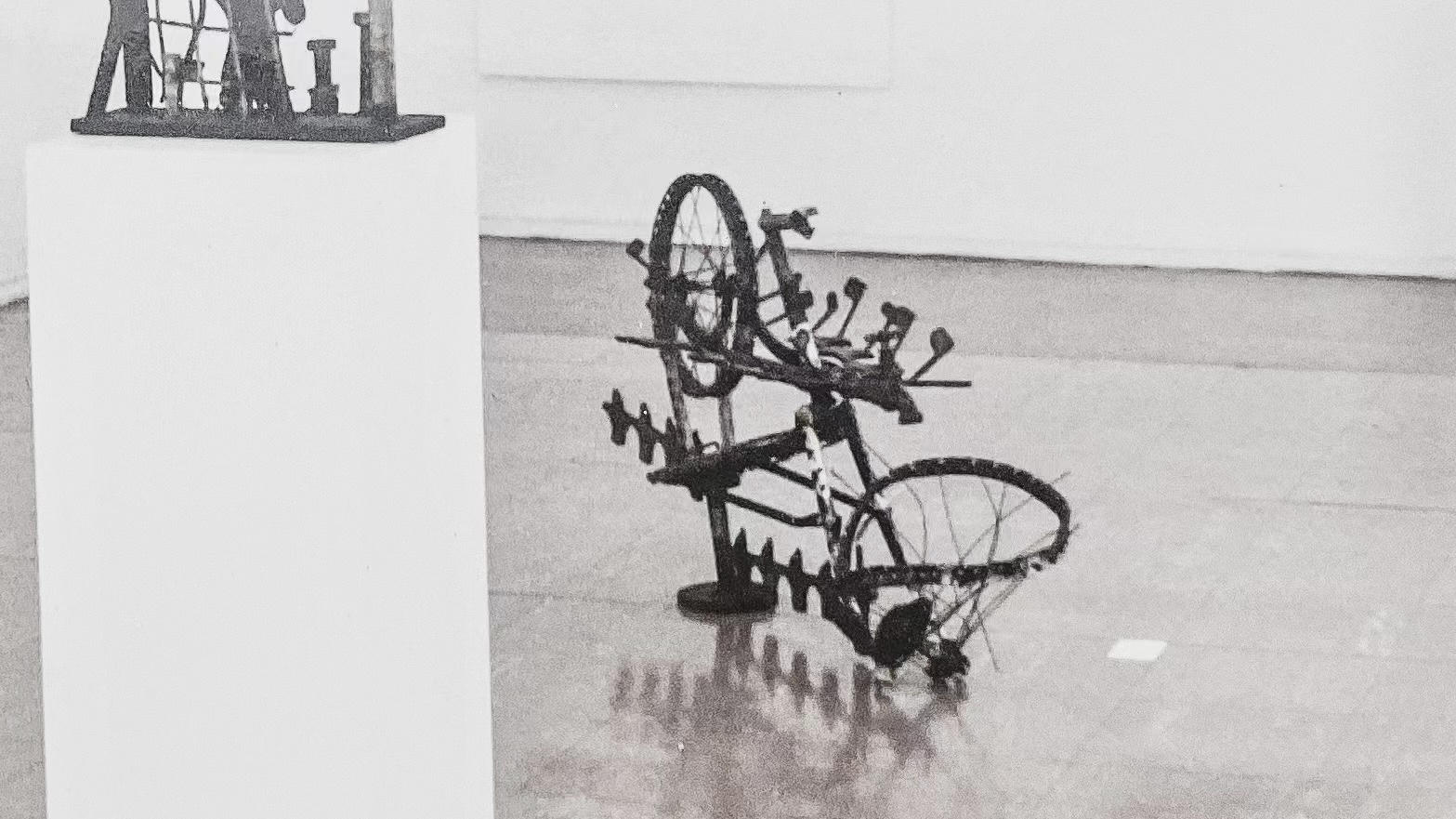

Nicole Goode’s unsettling works—that is, works of unsettling—speak, wordlessly, of unbecoming. Set in negative space, the two-part performance is characterised by bared underbelly, exposed neck, and implied promises unfulfilled. It is in its “un”s, its negations, that the work becomes most concrete; the artist’s untimely body, graceful and irregular in its slowness, is less of a focal point than the disruptions that its presence creates. Linger (grind rail), Goode’s 60 minute movement performance (enacted on opening night), offered an eerie screen-to-life mirroring of Linger (break ramp), a 65-minute single-channel colour video that flickers projected from floor to ceiling upon the entry wall of PICA’s temporary warehouse abode. The live performance saw Goode entangle themselves carefully around and through the work’s metallic namesake. The steady delicateness of the artist’s extended limbs and arched frame gave the impression that Goode was supported by thickened honey. Goode’s subversive employment of skating equipment, a particularly austere steel frame exposed here and there under peeling cobalt paint, created a site of contestation. This unexpected mode of relating rendered sharply the lack of bodies and movements one anticipated. Through absence and aversion, Goode prompts the consideration of patterns of exclusion in a masculine-coded space. The discomfort afforded by Goode’s displacement was enhanced by a breakdown of typically contractual audience/performer relations. Subverting developmental logic, and reaching towards viewers with an almost unblinking gaze, Goode’s durational piece lived in the margins of social intelligibility. Disruption, however, was not manifested in distance. The artist’s bodily presence throughout Linger (grind rail) emphasised, with weighted physicality, the vulnerability implicit in “resisting expectations of movement and progress,” instilling the performance with tenderness. Softness is central, too. In Linger (break ramp), the artist tumbles down a large skate ramp (in what began as excruciatingly slow motion, until I settled into this new rhythm about ten minutes in). Goode’s performance borrows from skateboarders’ failures: the angular contortion of limbs and twisting of spines, wrapping each progression in fluidity and care. Even so, viewership is not an entirely peaceful experience. For at the heels of each gentle gesture snaps violence not yet rested into tangible form. Just as gravity seems to recognise it is robbed of crunched bone and split skin, so too is violence evoked by the slanted stares, dinged BMX bells, and chuckling leers of teenagers passing through the video’s frame. Imitation silver chains and hoodies emblazoned, like the park, with text bursting into spearheads where serifs should be, are unsettled by this quiet intervention. Goode’s temporality-warping acts of queering prompt consideration of alternative ways of being and moving within this ‘public’ space.

![]()

Grace Yong, 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology)

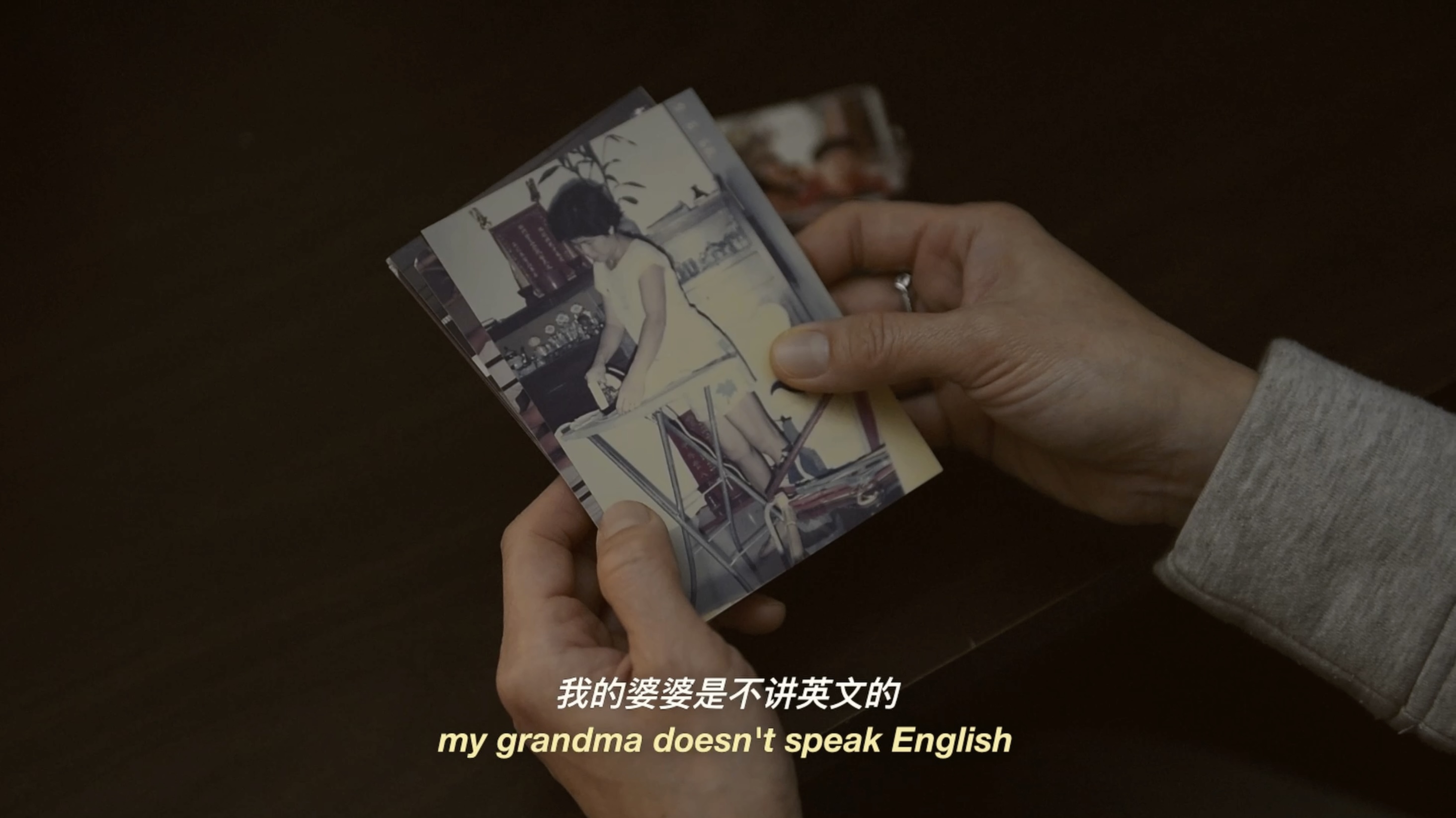

I can’t speak for everyone, but as a Southeast Asian woman raised in Western culture, I’ve often found myself in fascinating conversations with friends about the tradition of women taking their partner’s surname. Some of us imagine keeping our birth names, others consider hyphenation, and a fair few embrace the tradition. Grace Yong’s her name, an anthology, shown at this year’s Hatched, feels like an invitation to extend those conversations through a different cultural and historical lens. Gentle and introspective, the work is elegantly and thoughtfully composed, unfolding layers of meaning that invite the viewer to pause and reflect on the art of names. The video traces the way names carry lineage, tradition, and quiet currents of power, shaped by the push and pull of matriarchal and patriarchal customs. Layering image and text, it opens space for viewers to consider not just what a name means, but how it binds us to ancestry, shapes our sense of gender, and reflects the expectations of the world we move through. In earnest, I had low expectations for this video because it initially seemed overly direct and plain; yet, there is a quiet persistence to it. It’s the kind of work that lingers in your mind, unfolding its depth slowly, like a book you return to repeatedly, noticing something new each time. At certain moments, I found myself quietly enraged and confused, particularly when Yong uses phrases like “when she became a daughter” or “when she became a wife” to describe her great-grandmother’s name change. These words highlight a disheartening reality that as women, our surnames—our link to family and legacy—rarely stay with us or pass down through the maternal line. At birth, we are our father’s daughters; in marriage, our husbands’ wives; and the children we bear carry his name. Perhaps some of my frustration mirrors that of another Hatched nominee, whose work reflects on the biological truth that a woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have, formed while she is still a fetus inside her mother’s womb. In carrying a child, she also carries the potential for the eggs of her future grandchildren. But I digress. Watching Yong’s work, I felt a mixture of hurt, confusion, and indignation, torn between respect for tradition and frustration with a social practice that often feels arbitrary. However, I should clarify that I am not here to dictate whether anyone should keep, change, or hyphenate their surname; it is a deeply personal choice and one I remain uncertain of myself. Still, the work leaves you with a lingering awareness of how deeply names shape identity, lineage, and those quiet, often invisible, structures of gender in our lives.

![]()

Grace Yong, 她的姓氏,一篇历史 (her name, an anthology)

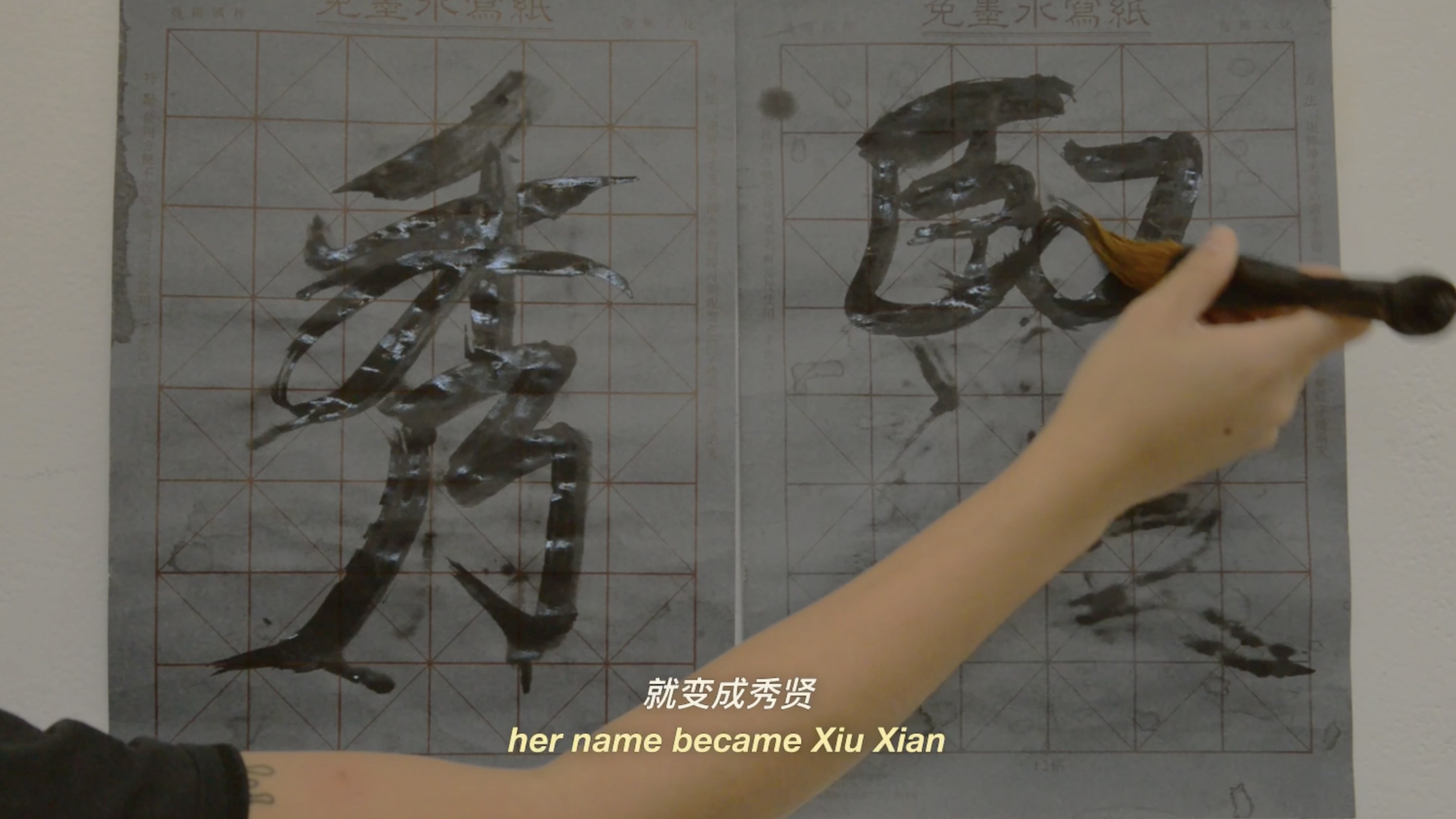

Nalinie See and I largely agree on points regarding Yong’s her name, an anthology (2024), but arrived at radically different conclusions. See states her angst at the fact that Yong describes her ah zo’s (great-grandmother's) names only in terms of her relationship with men, thereby categorising her only insofar as she exists within a patriarchal hierarchy. Superficially, this argument holds ground, since the narrator of the video, ostensibly Yong herself, states that her ah zo’s name (originally 张引治 (zhang Yin Zhi)), is pronounced in Hokkien to sound like “to attract or welcome brothers,” describing her parents’ desire for successive male children, while she later assumed the moniker 彭秀贤 (Peng Xiu Xian), having married into her husband’s family. Critically however, the voice-over is accompanied by intimate closeup shots of Chinese calligraphy, including of her ah zo’s name and family photographs. While the act of naming, writing/inscribing and photography all presuppose permanence and categorisation, by articulating objects within prevailing systems, Yong instead displays them in moments of flux—dissolving their associated hierarchies. This is most explicit in two places at the end of the video in which calligraphy and names collide. In the first instance, Yong writes her ah zo’s old name, Yin Zhi, and the name Peng Yu Zhi (彭玉治) in two separate columns. Since Peng Yu Zhi was another member of the Peng family, with a similar forename to Yong’s ah zo, the latter was forced to change her first name as well as surname upon marriage. Critically, slippage is introduced into the scene by the fact that Yong crosses her ah zo’s former name out, and instead sandwiches her new name above and below the old. This is only amplified by the next shot, as Yong uses water to again write the first iteration of her ah zo’s name, only for it to dry and disappear, before writing over it again with her new name. Hence, in both instances both the act of writing, as well as calligraphy are ridden with ambivalence, through crossing out or vanishing. Hence, even while Yong is presenting her ah zo in relation to men, the ambivalence introduces a moment of slippage and indeterminacy, utterly undermining those self-same categorical structures she describes. Where See sees this as a fault, I would argue that it is the power of the work.

![]()

Pippini Niamh, Come to the Table

Printmaking occupies a unique niche in the history of art. The delightfully strange effect of printmaking, combined with its easy reproducibility, has led to its use in protest and to disseminate information. It is in this unique social history that Niamh situates her practice. Composed of two separate works, Niamh’s contributions to Hatched consist of a large black and white print, alongside the original woodblock which produced it. This is a quiet and yet considered inversion of printmaking practices, where too often the woodblock matrix is treated as a by-product. Niamh embraces the visibility of a creative process and celebrates the processual history of her prints. Furthermore, Niamh refutes the traditional wooden block by carving into the surface of a found wooden table instead of a discardable cube. Together, the print and the found-table-turned-matrix leaves a memorable image. Two chairs flank the table, one slightly ajar and inviting viewers to sit. With the work at the table is a question left unanswered. The print is gorgeous, detailing an overflowing banquet inscribed with the opening of the Lord’s Prayer ‘Give us today our daily bread.’ The abundant reference to food and other text swirling over the prints speaks to the vast question of global food equality that pervades our contemporary age. Altogether, a stunning reinvention of a popular medium—Niamh offers an engaging and meaningful contribution to Hatched.

![]()

Silki Wong, Grip

Grip floods me with a rush of sweet and arbitrary memories. In its wrinkled fabric I encountered the comforting banality of my grandmother’s apartment, where most of my early childhood was spent. I forgot, until seeing this work, the amber beads she kept on her dresser but never wore, and the parsley she grew on her balcony, sundrenched in its terracotta pot. Perhaps it is the soft colours that drew me back to this long-ago space of safety. Banners of pale periwinkle, soft sage, and inviting indigo float cloudlike from wooden poles. Hanging both upwards and downwards they are unmoved by the hurry of wind or gravity, giving them the kind of fond aloofness that one encounters in practiced daydreamers. It is in this quiet way that Silki Wong’s unassuming pastels dissolve thresholds of forgetfulness. Seemingly free of the demands of a bustling world, they become gently tethered reference points for well-worn comforts passed. I feel sure that where I meet again worn green sofas and tins of cross-stitch thread, others beside me waft through their own sacred collections of chocolate wrapper treasures. Wong’s coloured fabric rectangles shine through their snowy veils, illuminated as the stained glass shadows cast by spring leaves in the morning sun. Beautiful and wilted, the work is lit from within by the warmest golden threads that draw together eight billion everydays.

Images courtesy of the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. Documentation photos by Rebecca Mansell.

— Sam Beard

Germaine Chan, It’s the Revelation

The jumble of exposed beams, air vents, and modern skylights in PICA’s Forrest Chase venue for Hatched 2025 unexpectedly elevated the annual graduate show. Finally, young artists were placed in a room that reflected the world their generation experiences: gritty, exposed and over-engineered. The context of this fresh venue gave the works greater relevance and timeliness, even though overall there was a strong material and conceptual adherence to the previous iterations of the exhibition—after all, the arts students may change, but the art educations they receive year after year primarily remain the same. One surprising development was the selection of a contemporary painting from UWA, whose Hatched contributions in recent years have evidenced a preference for students embracing less-traditional mediums (in contrast with Curtin, which routinely champions its graduating painters). UWA student and mixed media artist Germaine Chan’s contribution to Hatched, It’s the Revelation, revives historical religious painting for a contemporary context. Across her panoramic scenes, Chan’s assorted fragments of morally dubious stick-figures in ugly, human gesticulations offer a discursive reflection on contemporary inter-personal entanglements. But Chan’s genius is not in the story she tells. The real highlight of It’s the Revelation is that despite sharing with almost every other work at Hatched the feature of visually ambiguous composition, it engages this contemporary convention without compromising Chan’s idiosyncratic expression and singular artistic identity. It is this kind of artistic innovation, of using ubiquitous and stale tools to solidify one’s distinctive artistic identity, that sees Chan carving out a space for herself within—what usually feels like—a cyclical contemporary artworld. Chan’s repackaging of a ubiquitous way of working resonates with Hatched 2025, which is itself an unironic attempt to restyle the old, improving it, whilst bypassing the struggle of starting from scratch. These innovations prove that consistency does not require conformity and that Hatched may still have more to give us.

— Maraya Takoniatis

Litia Roko, 500mL/point

In today’s world, it’s a Sisyphean task to locate an artist who hasn’t been affected by the rise of generative artificial intelligence. A society already inundated with a crippling inability to engage in arts, now believes that meaningful images can be produced by an algorithm regurgitating probabilistic pixels and slop. It is no surprise a collective exhibition of recently graduated and emerging artists would grapple with this existential challenge. Litia Roko’s work 500 mL/point satirises this looming challenge to art practices by presenting her own cost benefit analysis of using AI. The name itself refers to the drastic water usage AI servers require to prevent themselves from combusting. The most resonant area of her video was the open criticism of the Living Museum App. This supposedly pedagogical resource claims to use AI to bring objects from the British Museum to life. The ethical authority of western programs—notorious for their wealth of stolen heritage—is already obviously problematic, yet Roko’s video intensifies the distressing qualities of rampant AI, reflecting its true scale. She draws attention to the ways that algorithms privilege the information they have been fed, and how this can be weaponised to produce narratives that obscure and mystify the truth. For instance, in 500mL/point a Moai head claims, “I love it here,” though of course it can only speak with what data it has been fed. By so openly confronting the issues that arise when artistic practice melds with generative machinery, Roko’s work leaves any viewer more assured of the absolute inherent and indispensable worth of the human element in artistic and academic practices.

— Riley Landau

Nicole Goode, Linger (grind rail) and Linger (break ramp)