This text is published in collaboration with Guan Kan Journal. Find out more about Guan Kan here.

On a hot, humid afternoon in June 2024, famed Chinese painter Qi Zhilong welcomed a group of UWA students into his Beijing studio. I was tagging along on a trip organised by Tami Xiang and Darren Jorgensen. For days we’d been crisscrossing Beijing, visiting crowded studios and white-walled galleries, meeting and interviewing artists. After days of unfamiliar sights, Qi Zhilong’s studio stopped me short. I’d been here before, five years earlier, on the same student program. Familiar sculptures stood across the concrete floor. Paintings, some works in progress, leaned against the grey studio walls. Recognised for his ironic paintings of revolutionary women dressed in Mao-era attire, Qi became one of leading figures in China’s 1980s Gaudy Art and Political Pop movements. After discussing his works with the students, Qi led us downstairs to a lunch he and his wife had prepared for us. In the basement of his studio-home, an alcove was set up with drums, synths, and a long Mongolian horn. As we chowed down on a late lunch and drank, Qi and his friends began jamming—long improvisations with Qi playing a droning bass, while fellow artists played the horn, synths, and drums. The players soon swapped instruments with students, pausing only to eat, drink, and smoke as the long jam played on.

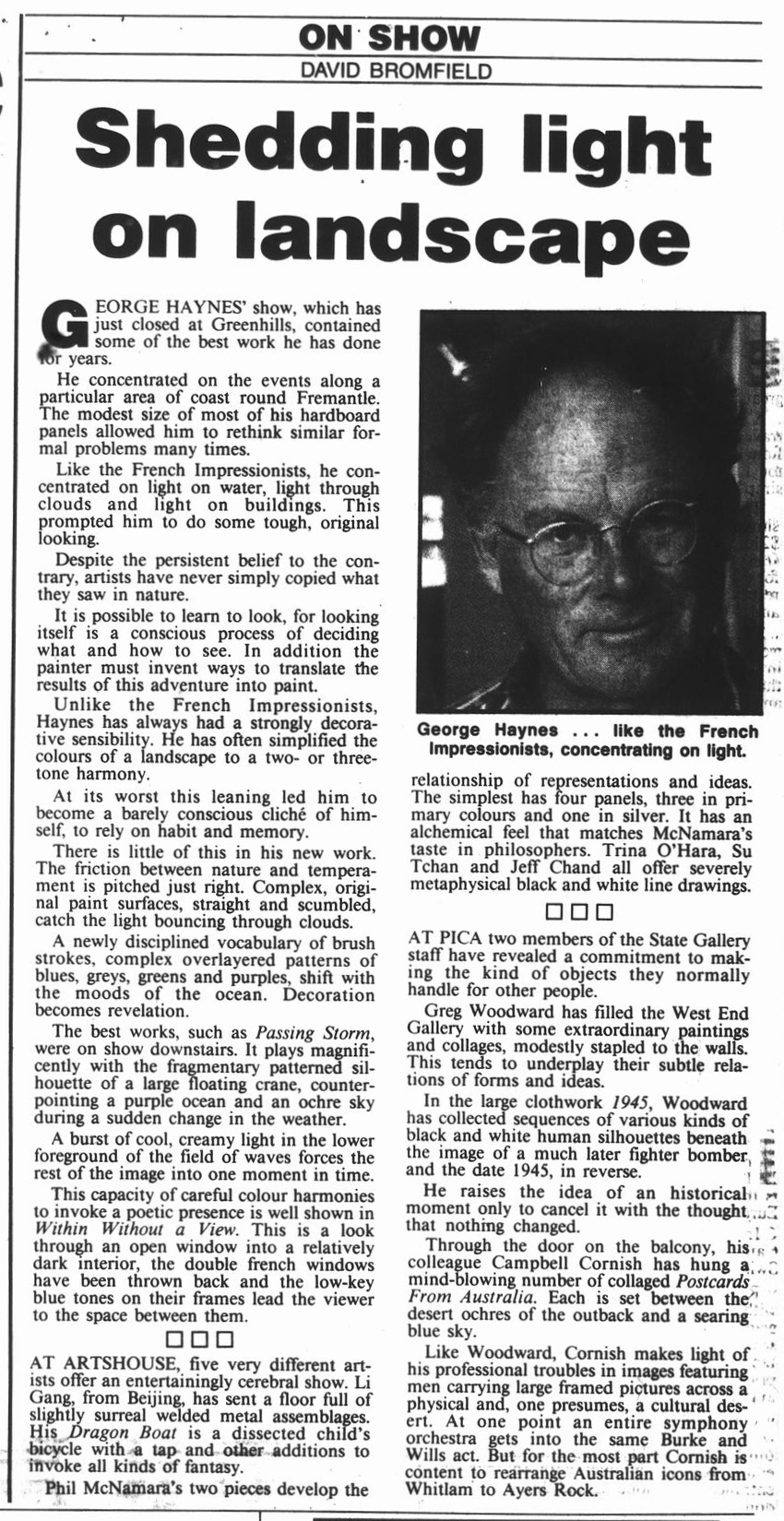

At some point, I was waved over to a conversation. Darren and the man who had been stoically twiddling the synth were both leaning back on monobloc chairs, chatting and sipping baijiu. The musician was Li Gang, who, it turns out, is also an artist. Li was surprised to learn we were from Western Australia and quickly explained that he had studied in Perth in the 1990s. He asked what I did. “I write art criticism,” I replied. Again, to my surprise Li began sharing stories about the late critic David Bromfield (who had only recently passed away), sculptor Tony Jones, and Li’s own exhibition at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA). Li recounted one particular story I’ve heard several times: of a painting by George Haynes depicting Bromfield as a chicken being strangled by the artist (or at least that’s how I remember it!). In a sprawling city of 21 million people, on a trip where the itinerary shifted at a moment’s notice, kicking back and listening to artworld tales from ’90s Perth felt utterly surreal.

We stayed in touch, and what follows are some of Li’s reminiscences of his time studying at the Claremont School of Art in the early 1990s, alongside images he kept from those years. This chance meeting reminded me, in stark clarity, that while it may be entertaining to amuse ourselves with Perth’s isolation and size, in reality the city has always been a cosmopolitan place (how much so varying only on one's perspective and definition), perhaps even long before it thought of itself as such. However, for all its cosmopolitanism, the Perth Li arrived in was a troubled place for the Asian diaspora community. In the late 1980s, a wave of racist poster campaigns and violent attacks targeted Asian businesses, perpetrated by members of Perth’s Neo-Nazi group, the Australian Nationalist Movement. Led by the moustachioed racist Peter Joseph “Jack” Van Tongeren, the group was linked to the firebombing of several Chinese restaurants across the city. Yet, Li recalls a kinder experience—of the generosity of fellow students and teachers who helped him settle in and advance his studies. Eventually, Li moved to Melbourne before returning to Beijing, having recognised the limitations of Perth’s artworld for sculptors and the difficulties he faced exhibiting his work within its then-conservative gallery circuit.

The following is based on an interview with Li taken several months after our initial meeting.

Li Gang: Actually, the first time I tried to go to Kansas City in America, but my application to art school there was rejected, then I applied for art school in Adelaide. My third application was to Perth. A friend of my father at the time, she knew some people organising English lessons at a school called Buckland College. So, I got a visa and came to Perth. I had never heard about Perth; only Melbourne, Sydney, maybe Brisbane, something like that. I was quite dramatic at the time, having applied twice to study art and being rejected. So, for the third application, I decided to change subject and study mechanics. I think it was 4 October 1990 that I arrived in Perth. I attended Buckland College to study English, as well as mechanics. I lived in Mosman Park and cycled to the college which was only 10 minutes away.

I didn't like mechanics. At the same time, I had a friend who was studying with me at Buckland College. He was a painter, often painting portraits. He had a girlfriend, and the pair encouraged me to study art. Another painter friend, Perdita Phillips—I still remember her well, she was very nice. I told her too that I wanted to study art. She checked the newspaper, found a class at the Claremont School of Art, saying, “today's your last day to enrol!” So, she rushed me there—we drove down and I enrolled. By day, I would study my English, still learning words for the mechanics classes—“gearbox”, “windscreen wiper”, and so on—and every Thursday night from 6 to 8pm, I would attend sculpture classes. I studied with Tony Jones. He taught me how to make clay figures and armatures. Tony gave me a good mark, which helped me to apply for full-time study. I'm really grateful to Tony and Perdita for this.

![]()

I really wanted to study art full-time, but I was told that I couldn't change in the middle of my mechanics class. Then, the following week, Buckland College, where I was studying, suddenly went bankrupt! Suddenly the school no longer existed. Apparently, the principal's wife took the money to gamble in Singapore and lost it all. It was big news at the time: the first private college to go bankrupt in Perth, apparently. So now I had an opportunity to change from mechanics to art! I had to pass an English test, so it took me another six months to start at the Claremont School of Art, but I eventually did. I took my portfolio—including sculptures I made during that initial class with Tony Jones and photos of work I made in China—down to the School and met with Robin Phillips, who was a senior lecturer there. He thought it was very good. I'm really grateful to Robin for accepting me. In China, you have to sit a drawing exam. Here, I was able to get in just through this meeting with Robin.

I studied there for three years, even taking some art history classes. That subject was the most difficult, because I had read about contemporary art and modern art history, but in Chinese, so while I remembered all those names—the Impressionists, Cubists, etc—I had to relearn. But I passed, no problem. It's a long story, but to get into the Claremont School, it was a big moment for my art career. I remember all those people very well: Tony Jones, Robin Phillips, Arthur Kalamaras, John Fairhall, Rosemary Hunter and Drew Armstrong, who both taught art history. Rosemary was very nice—she knew I had a hard time with English, so helped me a lot.

Before coming to Perth, in China the door was still closed to a lot of Western art. So we never really had the opportunity to see many big shows. The only big exhibition I remember in Beijing was a Robert Rauschenberg show in 1986 or something like that. That was the first contemporary show I remember seeing in China. It was a big shock to us. But in Perth, I remember a very big Picasso show, and an exhibition called Mao Goes Pop, which was the first time they brought Chinese contemporary art to Perth, I think. A lot of great photography shows too. Tony Jones would encourage me to participate in competitions. He also introduced me to Gomboc Gallery and helped me to get my work in their sculpture park.

![]()

![]()

![]()

At the School, we'd hold these barbecues sometimes and talk about art and politics, and get a little drunk. And I would talk a lot—maybe a little too much! But it was a really great time for us to connect. Every Saturday we'd buy the newspaper and read the reviews by David Bromfield. There were a few critics, and every student would read them and talk about them in class the next week. At that time, PICA had only just opened. I remember seeing some Japanese minimalist art there. It was beautiful in that big space. I remember this Hong Kong guy who did a performance downstairs where he would cook for you—you'd make an order, and he'd cook for you, and learn about culture through cooking. And one Japanese artist used a big boat carved in wood and filled it up with water, in the boat—it was fantastic! There were a lot of different people around. One of the things I liked about the School was there were people of all different ages—one guy who studied sculpture was 80 or something. All these different people, with different backgrounds, bringing their knowledge to the School. After my three years of study in Perth, I moved to Melbourne to study for two years at the Victorian College of Art. Most of the students at the VCA were young students who had just graduated from high school. I missed the diversity of people that was at Claremont—mixing with a lot of interesting people with different backgrounds.

In Perth at that time, it was very hard to find opportunities to show my work. On the campus, there was a gallery to show your work, where we held a few shows. At the time, near PICA, there was a small space called Arthouse Gallery, which was a gallery for fresh people like me. I rented galleries a few times and held shows with friends. The Moores Building in Fremantle was also a space we would have shows in—our second or third show. Because I was a sculpture major, I would show mostly at Gomboc Gallery. Some teachers of mine would show there, like Claire Bailey. Big metal figurative work was popular at the time. I had some figurative work, but most of mine was more abstract. Abstract sculpture was harder to show in Perth at that time. People liked the figurative stuff, like Hans Arkeveld, Tony Jones, Claire Bailey, Stuart Elliot. They were all very popular and dominated sculpture then. For me, a Chinese student, I figured that—given the limitations to show my work—I should try and study elsewhere. I was thinking of Sydney or Melbourne. I asked my art history teacher Rosemary, and she recommended Melbourne. It was better than Sydney, she said. Rosemary Hunter gave me a lot of help. Sometimes she would give night classes. She would drop me off afterwards at my place on Newcastle Street in Perth, even though she lived in Nedlands. I'm still very grateful for that, and remember her small Honda.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Before I came to Perth, I worked in a factory in Beijing. It was a tricycle factory. That’s where I learned welding and would use square metal and offcuts to make sculptures at night in Beijing. It was photographs of those sculptures that I showed Robin to get into the Claremont School. At the School, I focused on sculpture, making many bronzes. I remember on the day I went to enrol, I looked through the sculpture department—through the glass doors—and saw a big bronze figure standing there, like two metres tall. I was very impressed, and I told myself, well, I want to learn how to make bronze sculptures. Later, I learned that it was my teacher's work, Arthur Kalamaras. He taught us how to make models with the wax and cast the bronzes. After studying at the VCA, I went back to China and set up a studio for metal sculpting. Lots of welding and that sort of thing. Around the same time, I set up a bronze foundry in Beijing. I based it on the setup I learned from at the Claremont School. We’d make the wax models and take them to Wembley Tech once a month, which had a small foundry.

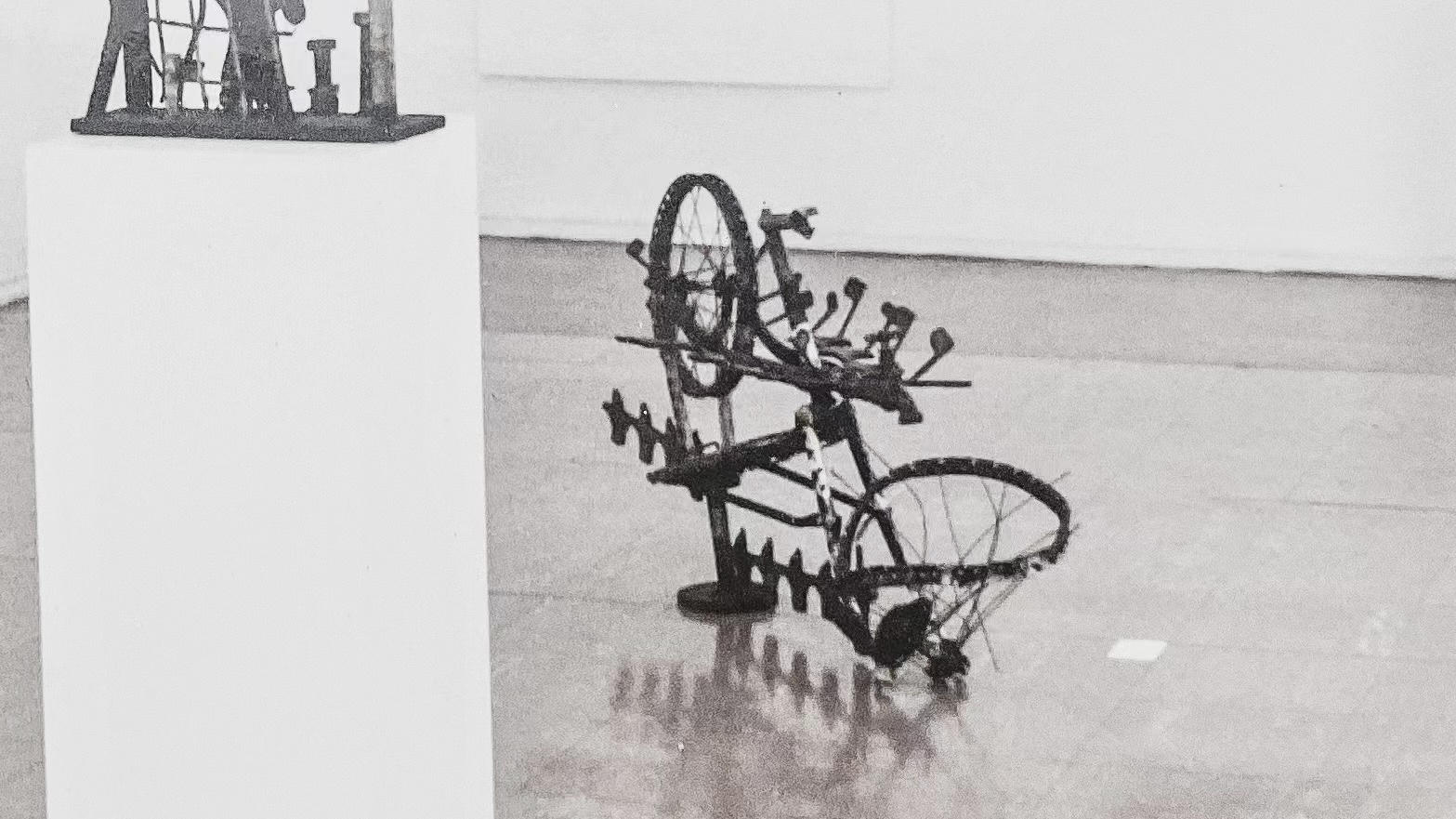

At the same time as all of that bronze casting, I was really interested in welding. There was a metalworking area with piles of old metal that nobody used. The metals were donated from the shipyards—offcuts and other items. I was one of the first students to use that old material. Another was John Grono, who used metal and cement. He’d make these large armatures and set them in cement, big and heavy. I focused on metalwork, casting bronzes and welding. For three years, I made sculptures that were half-figurative, half-abstract. I exhibited some of these at Arthouse Gallery, which David Bromfield saw and wrote about—that was fantastic!

![]()

There was a studio out the back of the sculpture department at the School. In that shed, I could do a lot of welding and grinding, and make a lot of noise. I remember all the technicians really well. We’d borrow the tools from one tech, Paul Hutchins, who was Welsh and managed the tools. Every morning at 9 am, we’d go to his room to borrow tools—goggles, grinders, and welding machines. By 4 pm, Paul would come out with a notebook to collect the tools. Sometimes we wouldn’t like to see him! When he showed up, that would mean we’d have to stop working and return the equipment. He’d be very strict. “Give the tools back! Now it’s time to leave.” That’s Paul! But I liked him. He’d teach us how to use the tools safely. He was fantastic. After nearly three years, we used most of the old metal there. But people would often donate junk before it was thrown out. We’d use old cookers or things like that. For one sculpture, I used parts from an old motorcycle that Claire Bailey left there. I brought that sculpture from Perth to Melbourne, before shipping it to Beijing. Now, it’s still in my apartment in Beijing. I might have to send you some photographs. Alright. Ciao, ciao!

My sincere thanks to Li for generously sharing his memories and archive.

![]()

Images courtesy of Li Gang.

On a hot, humid afternoon in June 2024, famed Chinese painter Qi Zhilong welcomed a group of UWA students into his Beijing studio. I was tagging along on a trip organised by Tami Xiang and Darren Jorgensen. For days we’d been crisscrossing Beijing, visiting crowded studios and white-walled galleries, meeting and interviewing artists. After days of unfamiliar sights, Qi Zhilong’s studio stopped me short. I’d been here before, five years earlier, on the same student program. Familiar sculptures stood across the concrete floor. Paintings, some works in progress, leaned against the grey studio walls. Recognised for his ironic paintings of revolutionary women dressed in Mao-era attire, Qi became one of leading figures in China’s 1980s Gaudy Art and Political Pop movements. After discussing his works with the students, Qi led us downstairs to a lunch he and his wife had prepared for us. In the basement of his studio-home, an alcove was set up with drums, synths, and a long Mongolian horn. As we chowed down on a late lunch and drank, Qi and his friends began jamming—long improvisations with Qi playing a droning bass, while fellow artists played the horn, synths, and drums. The players soon swapped instruments with students, pausing only to eat, drink, and smoke as the long jam played on.

At some point, I was waved over to a conversation. Darren and the man who had been stoically twiddling the synth were both leaning back on monobloc chairs, chatting and sipping baijiu. The musician was Li Gang, who, it turns out, is also an artist. Li was surprised to learn we were from Western Australia and quickly explained that he had studied in Perth in the 1990s. He asked what I did. “I write art criticism,” I replied. Again, to my surprise Li began sharing stories about the late critic David Bromfield (who had only recently passed away), sculptor Tony Jones, and Li’s own exhibition at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA). Li recounted one particular story I’ve heard several times: of a painting by George Haynes depicting Bromfield as a chicken being strangled by the artist (or at least that’s how I remember it!). In a sprawling city of 21 million people, on a trip where the itinerary shifted at a moment’s notice, kicking back and listening to artworld tales from ’90s Perth felt utterly surreal.

We stayed in touch, and what follows are some of Li’s reminiscences of his time studying at the Claremont School of Art in the early 1990s, alongside images he kept from those years. This chance meeting reminded me, in stark clarity, that while it may be entertaining to amuse ourselves with Perth’s isolation and size, in reality the city has always been a cosmopolitan place (how much so varying only on one's perspective and definition), perhaps even long before it thought of itself as such. However, for all its cosmopolitanism, the Perth Li arrived in was a troubled place for the Asian diaspora community. In the late 1980s, a wave of racist poster campaigns and violent attacks targeted Asian businesses, perpetrated by members of Perth’s Neo-Nazi group, the Australian Nationalist Movement. Led by the moustachioed racist Peter Joseph “Jack” Van Tongeren, the group was linked to the firebombing of several Chinese restaurants across the city. Yet, Li recalls a kinder experience—of the generosity of fellow students and teachers who helped him settle in and advance his studies. Eventually, Li moved to Melbourne before returning to Beijing, having recognised the limitations of Perth’s artworld for sculptors and the difficulties he faced exhibiting his work within its then-conservative gallery circuit.

The following is based on an interview with Li taken several months after our initial meeting.

Li Gang: Actually, the first time I tried to go to Kansas City in America, but my application to art school there was rejected, then I applied for art school in Adelaide. My third application was to Perth. A friend of my father at the time, she knew some people organising English lessons at a school called Buckland College. So, I got a visa and came to Perth. I had never heard about Perth; only Melbourne, Sydney, maybe Brisbane, something like that. I was quite dramatic at the time, having applied twice to study art and being rejected. So, for the third application, I decided to change subject and study mechanics. I think it was 4 October 1990 that I arrived in Perth. I attended Buckland College to study English, as well as mechanics. I lived in Mosman Park and cycled to the college which was only 10 minutes away.

I didn't like mechanics. At the same time, I had a friend who was studying with me at Buckland College. He was a painter, often painting portraits. He had a girlfriend, and the pair encouraged me to study art. Another painter friend, Perdita Phillips—I still remember her well, she was very nice. I told her too that I wanted to study art. She checked the newspaper, found a class at the Claremont School of Art, saying, “today's your last day to enrol!” So, she rushed me there—we drove down and I enrolled. By day, I would study my English, still learning words for the mechanics classes—“gearbox”, “windscreen wiper”, and so on—and every Thursday night from 6 to 8pm, I would attend sculpture classes. I studied with Tony Jones. He taught me how to make clay figures and armatures. Tony gave me a good mark, which helped me to apply for full-time study. I'm really grateful to Tony and Perdita for this.

I really wanted to study art full-time, but I was told that I couldn't change in the middle of my mechanics class. Then, the following week, Buckland College, where I was studying, suddenly went bankrupt! Suddenly the school no longer existed. Apparently, the principal's wife took the money to gamble in Singapore and lost it all. It was big news at the time: the first private college to go bankrupt in Perth, apparently. So now I had an opportunity to change from mechanics to art! I had to pass an English test, so it took me another six months to start at the Claremont School of Art, but I eventually did. I took my portfolio—including sculptures I made during that initial class with Tony Jones and photos of work I made in China—down to the School and met with Robin Phillips, who was a senior lecturer there. He thought it was very good. I'm really grateful to Robin for accepting me. In China, you have to sit a drawing exam. Here, I was able to get in just through this meeting with Robin.

I studied there for three years, even taking some art history classes. That subject was the most difficult, because I had read about contemporary art and modern art history, but in Chinese, so while I remembered all those names—the Impressionists, Cubists, etc—I had to relearn. But I passed, no problem. It's a long story, but to get into the Claremont School, it was a big moment for my art career. I remember all those people very well: Tony Jones, Robin Phillips, Arthur Kalamaras, John Fairhall, Rosemary Hunter and Drew Armstrong, who both taught art history. Rosemary was very nice—she knew I had a hard time with English, so helped me a lot.

Before coming to Perth, in China the door was still closed to a lot of Western art. So we never really had the opportunity to see many big shows. The only big exhibition I remember in Beijing was a Robert Rauschenberg show in 1986 or something like that. That was the first contemporary show I remember seeing in China. It was a big shock to us. But in Perth, I remember a very big Picasso show, and an exhibition called Mao Goes Pop, which was the first time they brought Chinese contemporary art to Perth, I think. A lot of great photography shows too. Tony Jones would encourage me to participate in competitions. He also introduced me to Gomboc Gallery and helped me to get my work in their sculpture park.

At the School, we'd hold these barbecues sometimes and talk about art and politics, and get a little drunk. And I would talk a lot—maybe a little too much! But it was a really great time for us to connect. Every Saturday we'd buy the newspaper and read the reviews by David Bromfield. There were a few critics, and every student would read them and talk about them in class the next week. At that time, PICA had only just opened. I remember seeing some Japanese minimalist art there. It was beautiful in that big space. I remember this Hong Kong guy who did a performance downstairs where he would cook for you—you'd make an order, and he'd cook for you, and learn about culture through cooking. And one Japanese artist used a big boat carved in wood and filled it up with water, in the boat—it was fantastic! There were a lot of different people around. One of the things I liked about the School was there were people of all different ages—one guy who studied sculpture was 80 or something. All these different people, with different backgrounds, bringing their knowledge to the School. After my three years of study in Perth, I moved to Melbourne to study for two years at the Victorian College of Art. Most of the students at the VCA were young students who had just graduated from high school. I missed the diversity of people that was at Claremont—mixing with a lot of interesting people with different backgrounds.

In Perth at that time, it was very hard to find opportunities to show my work. On the campus, there was a gallery to show your work, where we held a few shows. At the time, near PICA, there was a small space called Arthouse Gallery, which was a gallery for fresh people like me. I rented galleries a few times and held shows with friends. The Moores Building in Fremantle was also a space we would have shows in—our second or third show. Because I was a sculpture major, I would show mostly at Gomboc Gallery. Some teachers of mine would show there, like Claire Bailey. Big metal figurative work was popular at the time. I had some figurative work, but most of mine was more abstract. Abstract sculpture was harder to show in Perth at that time. People liked the figurative stuff, like Hans Arkeveld, Tony Jones, Claire Bailey, Stuart Elliot. They were all very popular and dominated sculpture then. For me, a Chinese student, I figured that—given the limitations to show my work—I should try and study elsewhere. I was thinking of Sydney or Melbourne. I asked my art history teacher Rosemary, and she recommended Melbourne. It was better than Sydney, she said. Rosemary Hunter gave me a lot of help. Sometimes she would give night classes. She would drop me off afterwards at my place on Newcastle Street in Perth, even though she lived in Nedlands. I'm still very grateful for that, and remember her small Honda.

Before I came to Perth, I worked in a factory in Beijing. It was a tricycle factory. That’s where I learned welding and would use square metal and offcuts to make sculptures at night in Beijing. It was photographs of those sculptures that I showed Robin to get into the Claremont School. At the School, I focused on sculpture, making many bronzes. I remember on the day I went to enrol, I looked through the sculpture department—through the glass doors—and saw a big bronze figure standing there, like two metres tall. I was very impressed, and I told myself, well, I want to learn how to make bronze sculptures. Later, I learned that it was my teacher's work, Arthur Kalamaras. He taught us how to make models with the wax and cast the bronzes. After studying at the VCA, I went back to China and set up a studio for metal sculpting. Lots of welding and that sort of thing. Around the same time, I set up a bronze foundry in Beijing. I based it on the setup I learned from at the Claremont School. We’d make the wax models and take them to Wembley Tech once a month, which had a small foundry.

At the same time as all of that bronze casting, I was really interested in welding. There was a metalworking area with piles of old metal that nobody used. The metals were donated from the shipyards—offcuts and other items. I was one of the first students to use that old material. Another was John Grono, who used metal and cement. He’d make these large armatures and set them in cement, big and heavy. I focused on metalwork, casting bronzes and welding. For three years, I made sculptures that were half-figurative, half-abstract. I exhibited some of these at Arthouse Gallery, which David Bromfield saw and wrote about—that was fantastic!

There was a studio out the back of the sculpture department at the School. In that shed, I could do a lot of welding and grinding, and make a lot of noise. I remember all the technicians really well. We’d borrow the tools from one tech, Paul Hutchins, who was Welsh and managed the tools. Every morning at 9 am, we’d go to his room to borrow tools—goggles, grinders, and welding machines. By 4 pm, Paul would come out with a notebook to collect the tools. Sometimes we wouldn’t like to see him! When he showed up, that would mean we’d have to stop working and return the equipment. He’d be very strict. “Give the tools back! Now it’s time to leave.” That’s Paul! But I liked him. He’d teach us how to use the tools safely. He was fantastic. After nearly three years, we used most of the old metal there. But people would often donate junk before it was thrown out. We’d use old cookers or things like that. For one sculpture, I used parts from an old motorcycle that Claire Bailey left there. I brought that sculpture from Perth to Melbourne, before shipping it to Beijing. Now, it’s still in my apartment in Beijing. I might have to send you some photographs. Alright. Ciao, ciao!

My sincere thanks to Li for generously sharing his memories and archive.

Images courtesy of Li Gang.