E.B. White is often credited with the line ‘explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better but the frog dies in the process.’ The opening lines of the wall label for Me, Also Me, AGWA’s most recent exhibition of works from the State Collection, are exemplary in this regard:

Fascinating, but so what? The use of this meme format, favoured by elder millennials to signal the quirky or dysfunctional aspects of their lifestyles, is perhaps more resonant with the lack of curatorial vision than with the actual works—which are themselves a curious selection of collection items old and new. This critic recommends brushing past this vapid and lazy conceit, as there is much to enjoy in this eclectic survey.

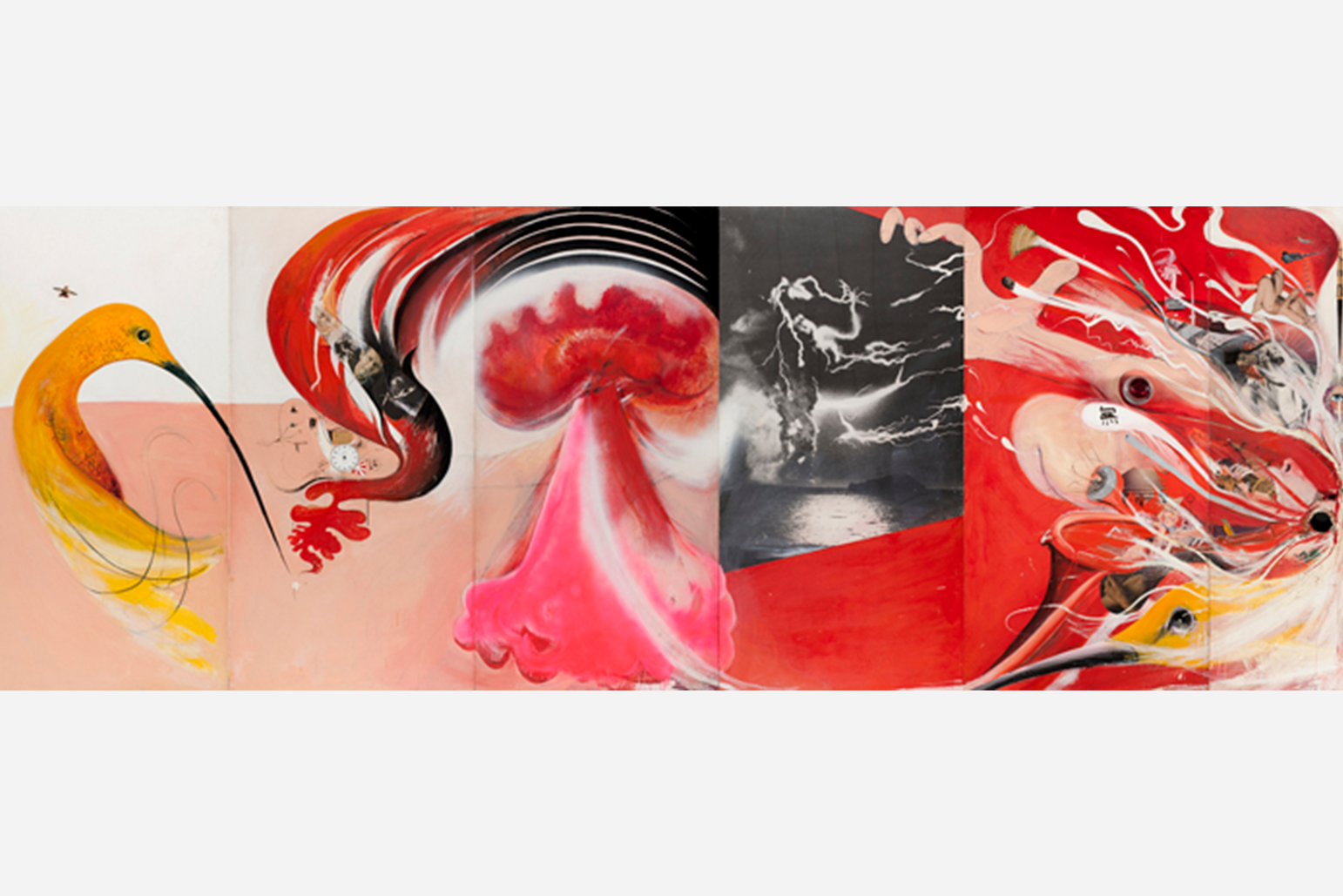

Foremost among these is Brett Whiteley’s The American Dream (1968-69). During the time Whiteley slaved over the eighteen-panel work, America was in crisis. The Vietnam War raged; Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had both been assassinated only a few months apart; and Cold War paranoia had most of the world frantically building backyard bunkers. Whiteley sought to condense the frenetic violence of American capitalism into a single image. It was the ‘ribbons of violence’ screaming from the television, the ‘dying capitolism [sic]’ in a country ‘de-boweling [sic] itself’ that Whiteley set about evoking in the main sequence of The American Dream.[1] Whiteley agonised about the painting for over a year. In the end it was dismissed by his dealer who refused to display it at the Marlborough gallery. Yet this is not some hackneyed story of the hero-painter a la David and Goliath (as it is often told retrospectively). Instead this is the story of a painter whose ambition outshot his facility—whose eagerness to outdo his American or European counterparts was fueled by his insecurity at being from Australia, on the so-called global periphery. Eventually The American Dream would be exhibited at Bonython Gallery, Sydney. Viewing the painting now, the legacy of 55 years of continued capitalism and global violence makes the work’s prognosis at best premature. This makes The American Dream a retrospective oddity, an enjoyable curiosity, and certainly revealing of the strengths and failings of paintings as predictions.

Juxtapose the simplicity of David Attwood’s Post New Hoover Intelligent Robots—a janky shrine to neoliberal labour conveyed with two Hoover vacuum cleaner robots mounted to a fluorescent backdrop—with the preposterous complexity of Whiteley’s painting. Attwood’s hoovers and The American Dream demonstrate two different dimensions of capitalist alienation: the servant-sucker Hoover-bots standing in for a hustling working class, too busy to clean their own dwellings any longer; and the implosion of the American dream as a fantasy, now impossible to view as anything more than a great mythical wank. Whiteley seems to depict this mythic masturbation in spurts and creamy globs across the central panels—it’s all a bit much. His were ideas too grandiose for painting, and too idealistic to have ever been a political reality. So in this regard, perhaps Whiteley came out on top, “realistically” depicting a failure.

Nearby is an equally monumental work by Ayoung Kim, an epic mix of anime-styled imagery wallpapered around a projection of the cinematic Delivery Dancer’s Sphere. The projection is a 24-minute blend of animation and live action footage filmed in the streets of South Korea. It’s an engrossing, mesmeric, and impeccably paced visual experience. Further around the gallery, Tracey Moffatt’s series Up in the Sky makes for an unusual selection. The same series having been shown only last year, in perhaps a more considered way, at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, leaves me to wonder if an alternative may have been available—like the five brilliant photographs by the late Destiny Deacon in the AGWA collection which have not been exhibited for several years.

An undercurrent of remembrance, reflection, and the questioning of myth and memory swirls amongst much of the remaining selections (Ian Burn, Mutlu Çerkez, and Farah Al Qasimi just to name a few), leaving one to wonder if the glibness of the ‘Me: X Also me: Y’ meme premise was even necessary. Instead, this conceit appears a beguiling attempt to simp to a younger audience hungry for authentic experiences that misses the mark in the process. Thankfully, this approach can be easily discarded by the viewer to the benefit of the work.

Me, Also Me is on display at The Art Gallery of Western Australia until 8 December 2024.

Footnotes:

1. As quoted in https://ashleighwilson.com.au/The-American-Dream

Artwork credits:

1. Brett Whiteley, The American Dream, 1968-69, mixed media on plywood. The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia.

2. David Attwood, Post New Hoover Intelligent Robots, 2023, Hoover intelligent robot vacuum cleaners, flourescent lights, acrylic, 142 × 34 x 22 cm. The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia. Photo: Dan McCabe.

Ayoung Kim, Delivery Dancer's Sphere, 2022, Single channel video, duration: 24 minutes. The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia. Purchased through the Art Gallery of Western Australia Foundation: TomorrowFund, 2022.

The title [...] is taken from the ‘Me: X Also me: Y’ meme widely circulated on social media. This meme is often used to humorously demonstrate the multiple realities people live in, the contradictory elements of life, and to perhaps release tension around the need to take unitary positions.

Fascinating, but so what? The use of this meme format, favoured by elder millennials to signal the quirky or dysfunctional aspects of their lifestyles, is perhaps more resonant with the lack of curatorial vision than with the actual works—which are themselves a curious selection of collection items old and new. This critic recommends brushing past this vapid and lazy conceit, as there is much to enjoy in this eclectic survey.

Foremost among these is Brett Whiteley’s The American Dream (1968-69). During the time Whiteley slaved over the eighteen-panel work, America was in crisis. The Vietnam War raged; Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had both been assassinated only a few months apart; and Cold War paranoia had most of the world frantically building backyard bunkers. Whiteley sought to condense the frenetic violence of American capitalism into a single image. It was the ‘ribbons of violence’ screaming from the television, the ‘dying capitolism [sic]’ in a country ‘de-boweling [sic] itself’ that Whiteley set about evoking in the main sequence of The American Dream.[1] Whiteley agonised about the painting for over a year. In the end it was dismissed by his dealer who refused to display it at the Marlborough gallery. Yet this is not some hackneyed story of the hero-painter a la David and Goliath (as it is often told retrospectively). Instead this is the story of a painter whose ambition outshot his facility—whose eagerness to outdo his American or European counterparts was fueled by his insecurity at being from Australia, on the so-called global periphery. Eventually The American Dream would be exhibited at Bonython Gallery, Sydney. Viewing the painting now, the legacy of 55 years of continued capitalism and global violence makes the work’s prognosis at best premature. This makes The American Dream a retrospective oddity, an enjoyable curiosity, and certainly revealing of the strengths and failings of paintings as predictions.

Juxtapose the simplicity of David Attwood’s Post New Hoover Intelligent Robots—a janky shrine to neoliberal labour conveyed with two Hoover vacuum cleaner robots mounted to a fluorescent backdrop—with the preposterous complexity of Whiteley’s painting. Attwood’s hoovers and The American Dream demonstrate two different dimensions of capitalist alienation: the servant-sucker Hoover-bots standing in for a hustling working class, too busy to clean their own dwellings any longer; and the implosion of the American dream as a fantasy, now impossible to view as anything more than a great mythical wank. Whiteley seems to depict this mythic masturbation in spurts and creamy globs across the central panels—it’s all a bit much. His were ideas too grandiose for painting, and too idealistic to have ever been a political reality. So in this regard, perhaps Whiteley came out on top, “realistically” depicting a failure.

Nearby is an equally monumental work by Ayoung Kim, an epic mix of anime-styled imagery wallpapered around a projection of the cinematic Delivery Dancer’s Sphere. The projection is a 24-minute blend of animation and live action footage filmed in the streets of South Korea. It’s an engrossing, mesmeric, and impeccably paced visual experience. Further around the gallery, Tracey Moffatt’s series Up in the Sky makes for an unusual selection. The same series having been shown only last year, in perhaps a more considered way, at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, leaves me to wonder if an alternative may have been available—like the five brilliant photographs by the late Destiny Deacon in the AGWA collection which have not been exhibited for several years.

An undercurrent of remembrance, reflection, and the questioning of myth and memory swirls amongst much of the remaining selections (Ian Burn, Mutlu Çerkez, and Farah Al Qasimi just to name a few), leaving one to wonder if the glibness of the ‘Me: X Also me: Y’ meme premise was even necessary. Instead, this conceit appears a beguiling attempt to simp to a younger audience hungry for authentic experiences that misses the mark in the process. Thankfully, this approach can be easily discarded by the viewer to the benefit of the work.

Me, Also Me is on display at The Art Gallery of Western Australia until 8 December 2024.

Footnotes:

1. As quoted in https://ashleighwilson.com.au/The-American-Dream

Artwork credits:

1. Brett Whiteley, The American Dream, 1968-69, mixed media on plywood. The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia.

2. David Attwood, Post New Hoover Intelligent Robots, 2023, Hoover intelligent robot vacuum cleaners, flourescent lights, acrylic, 142 × 34 x 22 cm. The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia. Photo: Dan McCabe.

Ayoung Kim, Delivery Dancer's Sphere, 2022, Single channel video, duration: 24 minutes. The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia. Purchased through the Art Gallery of Western Australia Foundation: TomorrowFund, 2022.